Похожие презентации:

Revision session

1.

Revision session(for ref./def. final exam takers/retakers)

2.

Relevant costs3.

Relevant costs can be defined as any cost relevant to adecision. A matter is relevant if there is a change in

cash flow that is caused by the decision.

• Relevant costs

– costs appropriate to specific management decisions

– these are represented by future cash flows whose

magnitude will vary depending upon the outcome of the

management decision made.

(Chartered Institute of Management Accountants)

4.

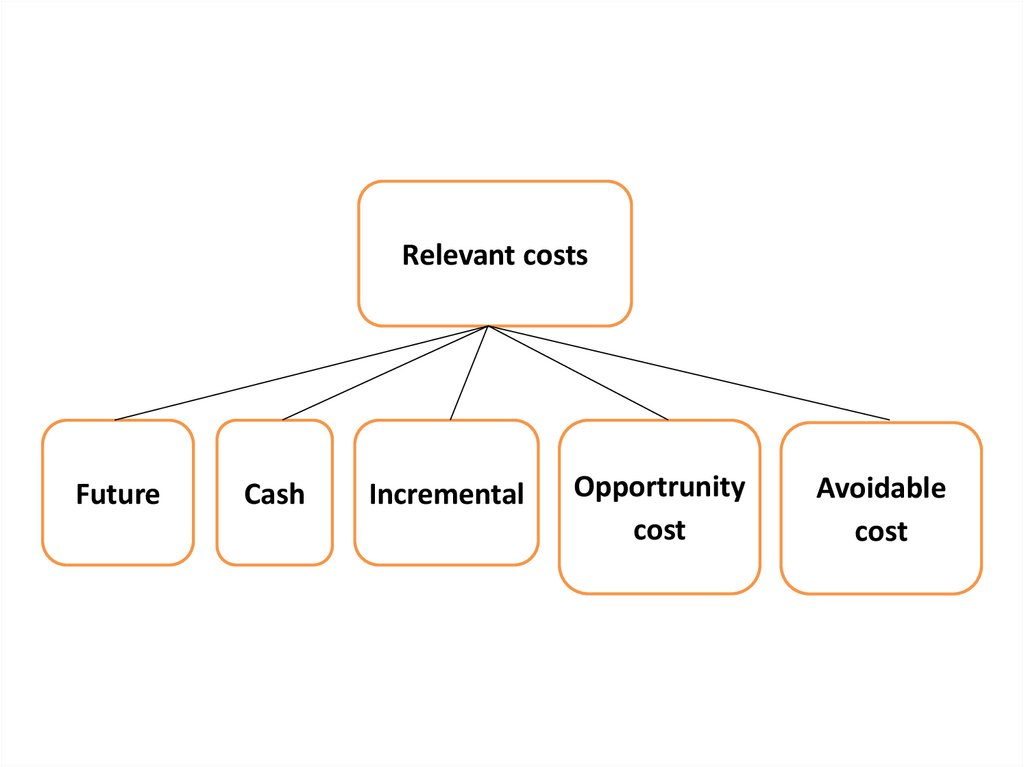

Relevant costsFuture

Cash

Incremental

Opportrunity

cost

Avoidable

cost

5.

Relevant costs are FUTURE costs.• They must occur in the future.

• A decision is about the future and it cannot

alter what has been done already.

• Costs that have been incurred in the past are

totally irrelevant to any decision that is being

made 'now'.

• Such costs are called past costs or sunk costs

and are irrelevant.

6.

Relevant costs are CASH FLOWS• This means that costs or charges which do not

reflect additional cash spending (such as

depreciation and notional costs), should be

ignored for the purpose of decision-making.

7.

Relevant costs are INCREMENTAL costs• It is the increase in costs and revenues that occurs as a

direct result of a decision taken that is relevant.

• Common costs can be ignored for the purpose of

decision making.

• For example, suppose a company decides to accept a

contract from a customer. An existing supervisor

currently earning $1,000 per month is given an extra

$100 per month for taking on the extra responsibility

associated with this contract. The incremental cost is

the additional salary paid to the supervisor ($100) –

the original salary of $1,000 was being paid anyway.

8.

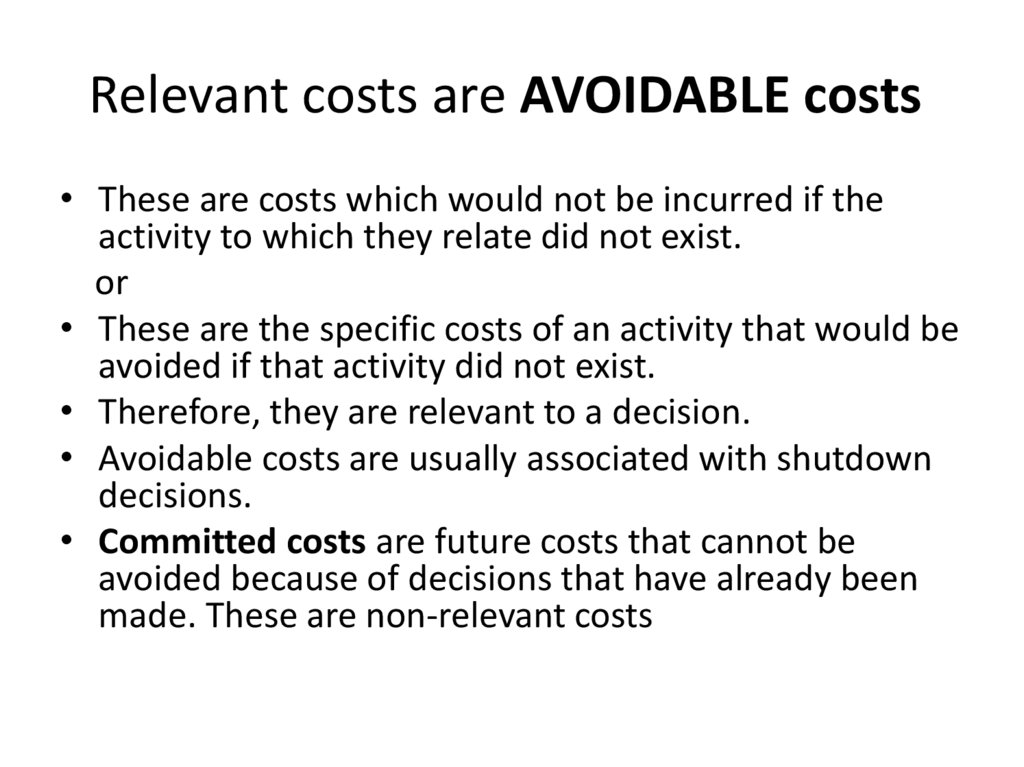

Relevant costs are AVOIDABLE costs• These are costs which would not be incurred if the

activity to which they relate did not exist.

or

• These are the specific costs of an activity that would be

avoided if that activity did not exist.

• Therefore, they are relevant to a decision.

• Avoidable costs are usually associated with shutdown

decisions.

• Committed costs are future costs that cannot be

avoided because of decisions that have already been

made. These are non-relevant costs

9.

Opportunity Costs• Opportunity costs only arise when resources

are scarce and have alternative uses.

• When an alternative course of action is given

up, the financial benefits lost are known as

opportunity costs.

• So they are the lost contribution from the best

use of the alternative forgone.

10.

11.

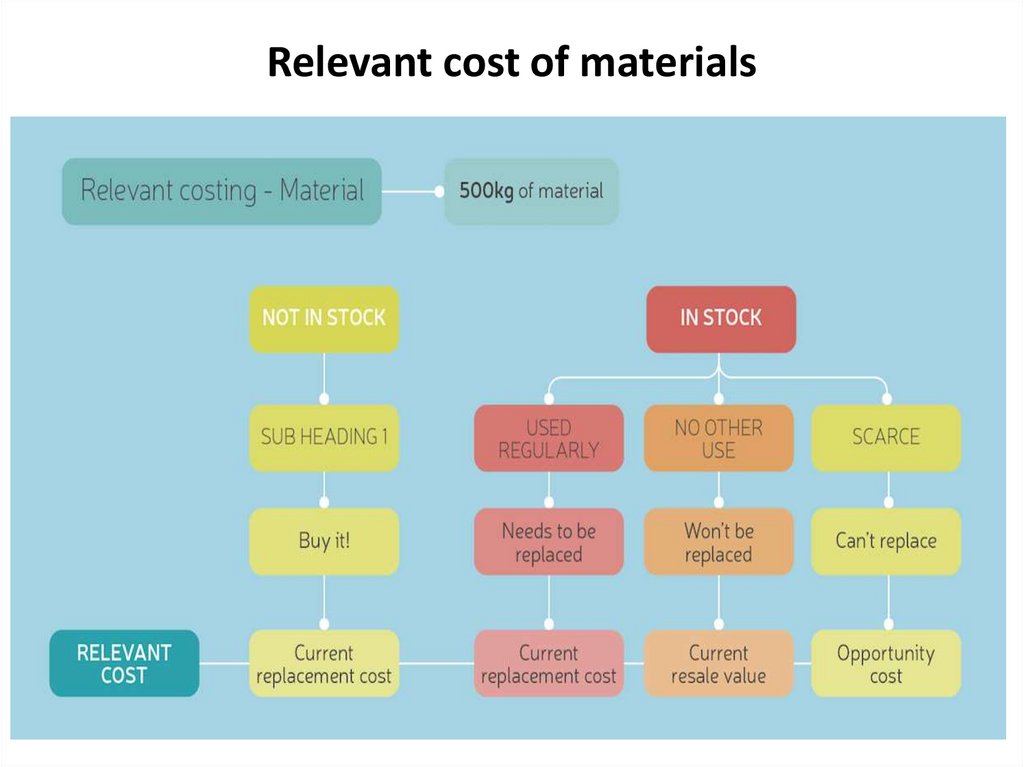

Relevant cost of materials12.

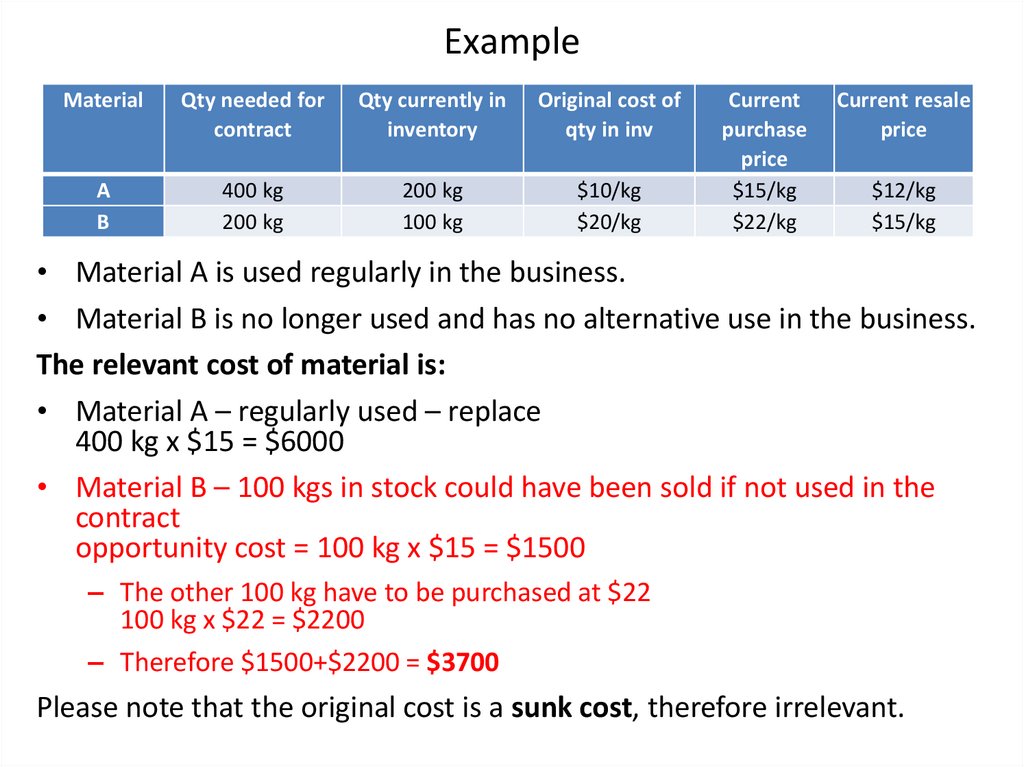

ExampleMaterial

Qty needed for

contract

Qty currently in

inventory

Original cost of

qty in inv

A

B

400 kg

200 kg

200 kg

100 kg

$10/kg

$20/kg

Current

purchase

price

$15/kg

$22/kg

Current resale

price

$12/kg

$15/kg

• Material A is used regularly in the business.

• Material B is no longer used and has no alternative use in the business.

The relevant cost of material is:

• Material A – regularly used – replace

400 kg x $15 = $6000

• Material B – 100 kgs in stock could have been sold if not used in the

contract

opportunity cost = 100 kg x $15 = $1500

– The other 100 kg have to be purchased at $22

100 kg x $22 = $2200

– Therefore $1500+$2200 = $3700

Please note that the original cost is a sunk cost, therefore irrelevant.

13.

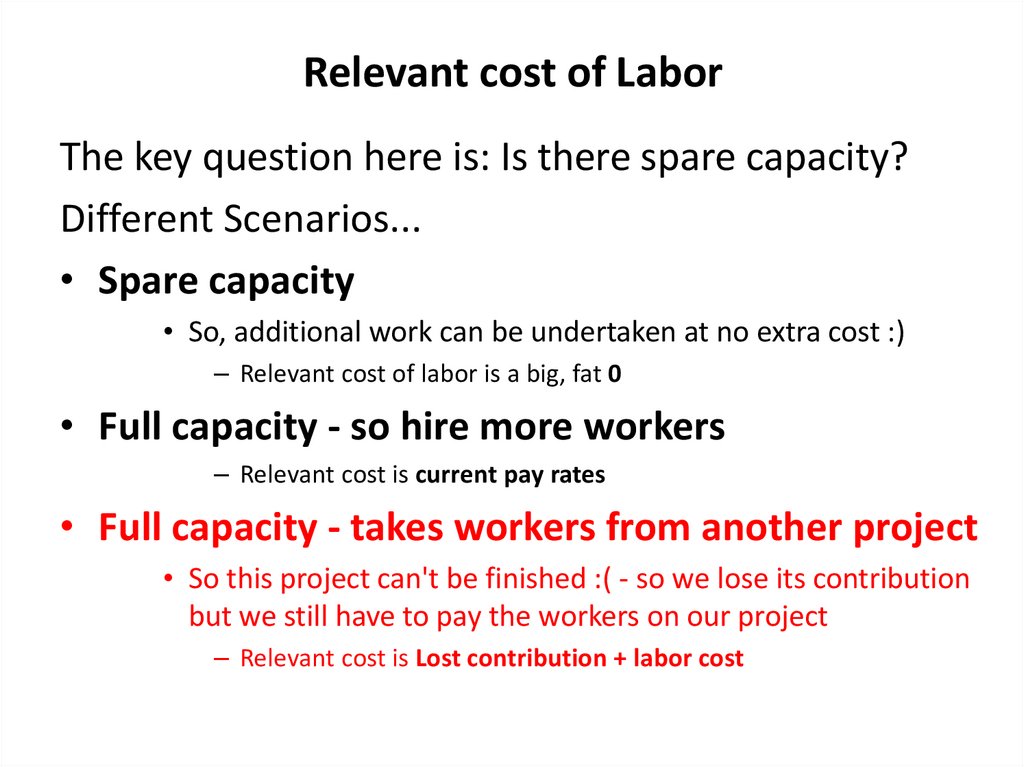

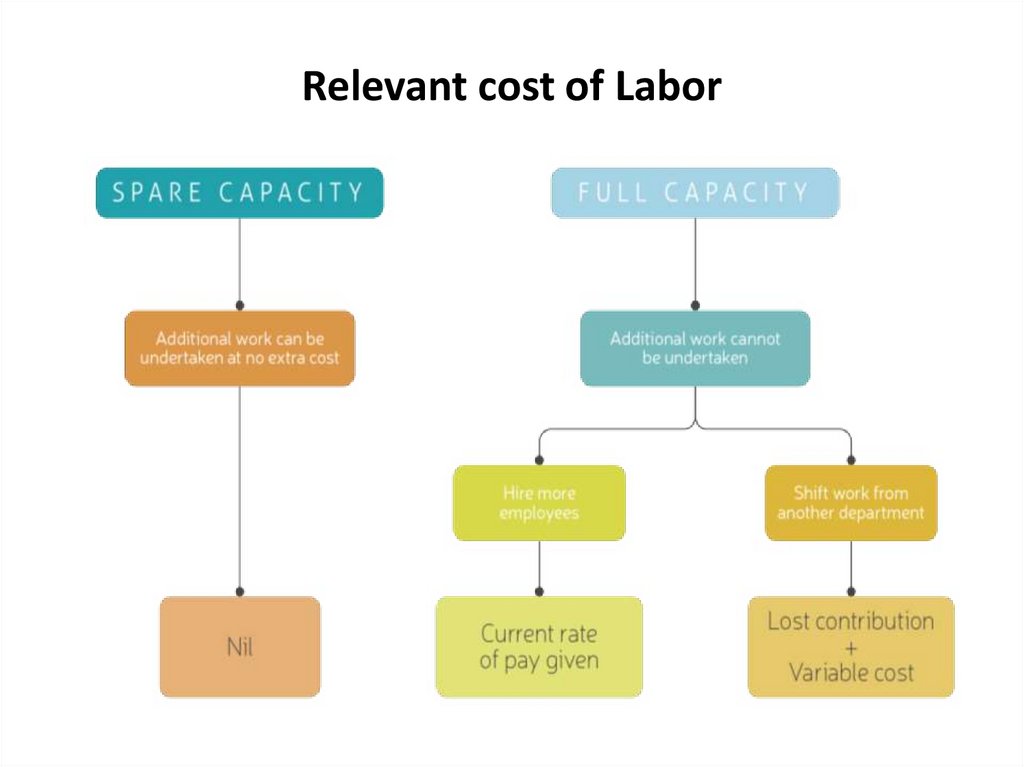

Relevant cost of LaborThe key question here is: Is there spare capacity?

Different Scenarios...

• Spare capacity

• So, additional work can be undertaken at no extra cost :)

– Relevant cost of labor is a big, fat 0

• Full capacity - so hire more workers

– Relevant cost is current pay rates

• Full capacity - takes workers from another project

• So this project can't be finished :( - so we lose its contribution

but we still have to pay the workers on our project

– Relevant cost is Lost contribution + labor cost

14.

Relevant cost of Labor15.

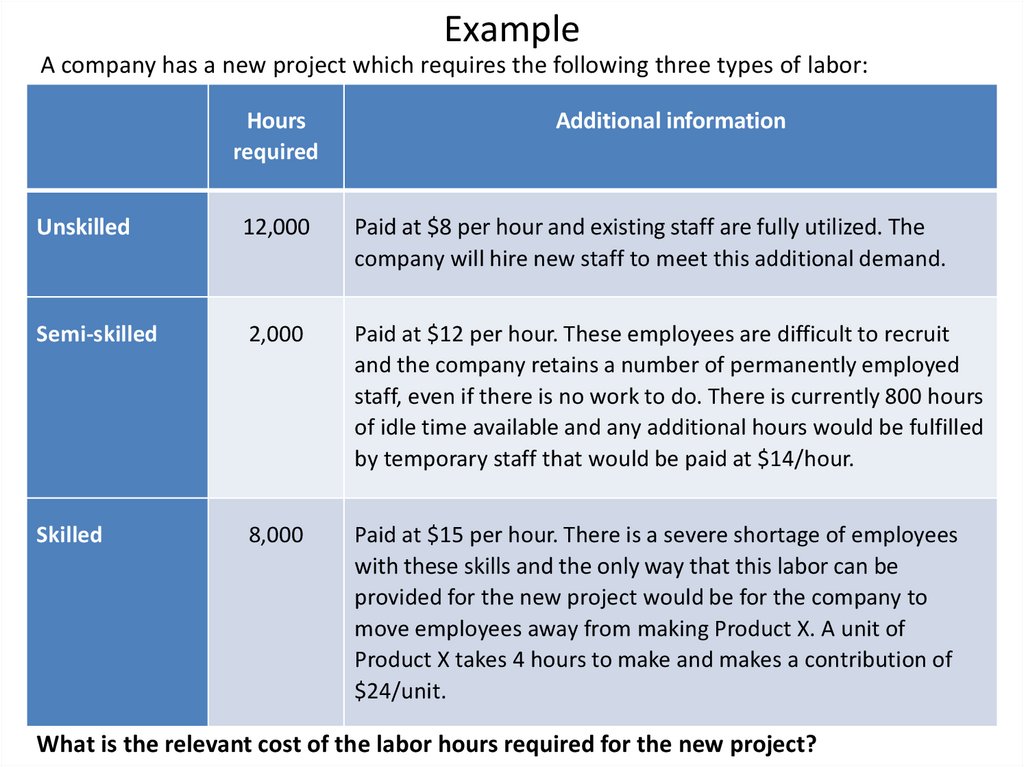

ExampleA company has a new project which requires the following three types of labor:

Hours

required

Additional information

Unskilled

12,000

Paid at $8 per hour and existing staff are fully utilized. The

company will hire new staff to meet this additional demand.

Semi-skilled

2,000

Paid at $12 per hour. These employees are difficult to recruit

and the company retains a number of permanently employed

staff, even if there is no work to do. There is currently 800 hours

of idle time available and any additional hours would be fulfilled

by temporary staff that would be paid at $14/hour.

Skilled

8,000

Paid at $15 per hour. There is a severe shortage of employees

with these skills and the only way that this labor can be

provided for the new project would be for the company to

move employees away from making Product X. A unit of

Product X takes 4 hours to make and makes a contribution of

$24/unit.

What is the relevant cost of the labor hours required for the new project?

16.

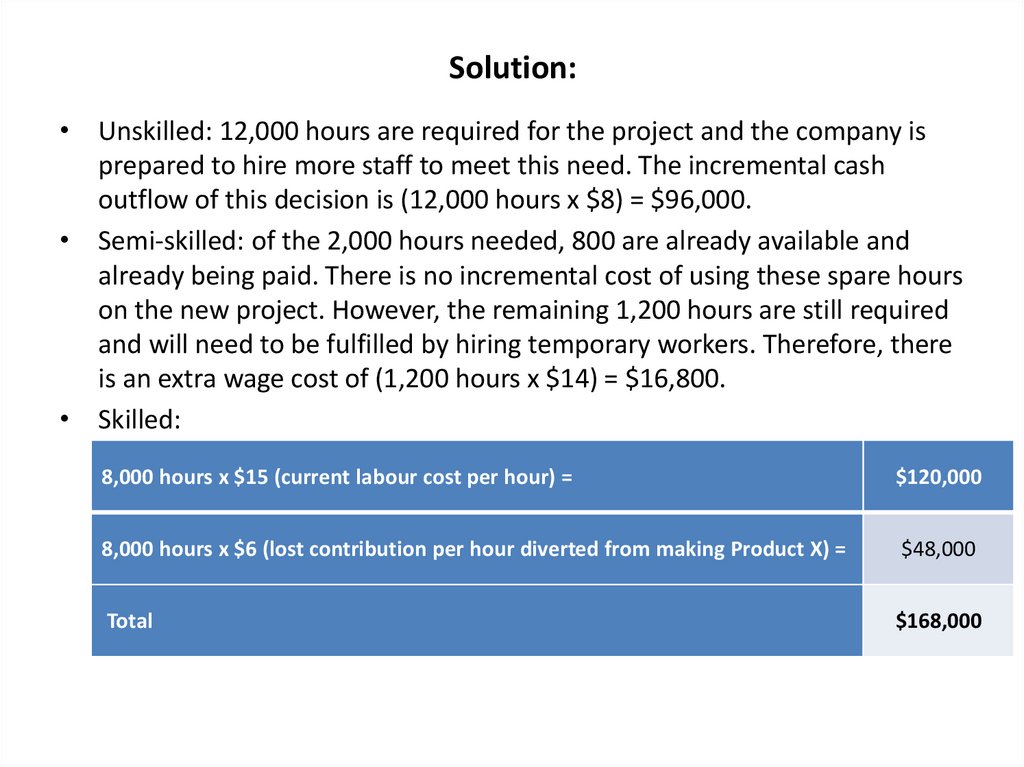

Solution:• Unskilled: 12,000 hours are required for the project and the company is

prepared to hire more staff to meet this need. The incremental cash

outflow of this decision is (12,000 hours x $8) = $96,000.

• Semi-skilled: of the 2,000 hours needed, 800 are already available and

already being paid. There is no incremental cost of using these spare hours

on the new project. However, the remaining 1,200 hours are still required

and will need to be fulfilled by hiring temporary workers. Therefore, there

is an extra wage cost of (1,200 hours x $14) = $16,800.

• Skilled:

8,000 hours x $15 (current labour cost per hour) =

$120,000

8,000 hours x $6 (lost contribution per hour diverted from making Product X) =

$48,000

Total

$168,000

17.

Relevant cost of Machinery• Repair costs arising from use

• Hire charges

• Fall in resale value arising from use

18.

Example• Some years ago, a company bought a piece of

machinery for $300,000. The net book value of the

machine is currently $50,000. The company could

spend $100,000 on updating the machine and the

products subsequently made on it could generate a

contribution of $150,000. The machine would be

depreciated at $25,000 per annum. Alternatively, if the

machine is not updated, the company could sell it now

for $75,000.

• On a relevant cost basis, should the company update

and use the machine or sell it now?

19.

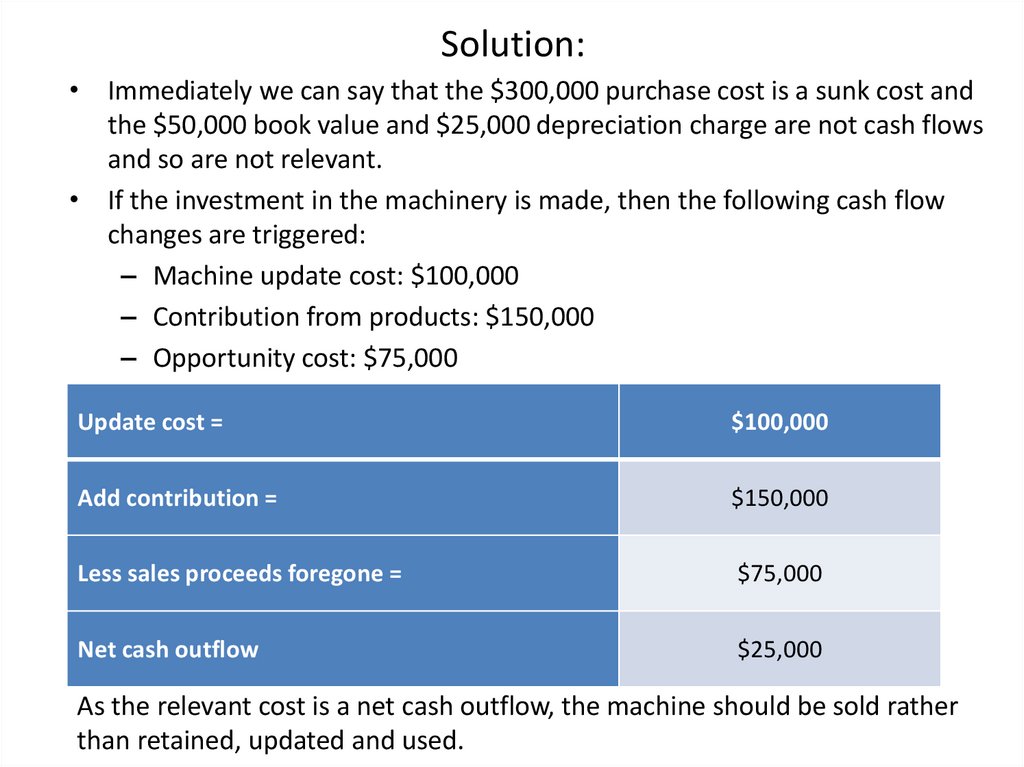

Solution:• Immediately we can say that the $300,000 purchase cost is a sunk cost and

the $50,000 book value and $25,000 depreciation charge are not cash flows

and so are not relevant.

• If the investment in the machinery is made, then the following cash flow

changes are triggered:

– Machine update cost: $100,000

– Contribution from products: $150,000

– Opportunity cost: $75,000

Update cost =

$100,000

Add contribution =

$150,000

Less sales proceeds foregone =

$75,000

Net cash outflow

$25,000

As the relevant cost is a net cash outflow, the machine should be sold rather

than retained, updated and used.

20.

Cost volume profit analysis(CVP analysis)

21.

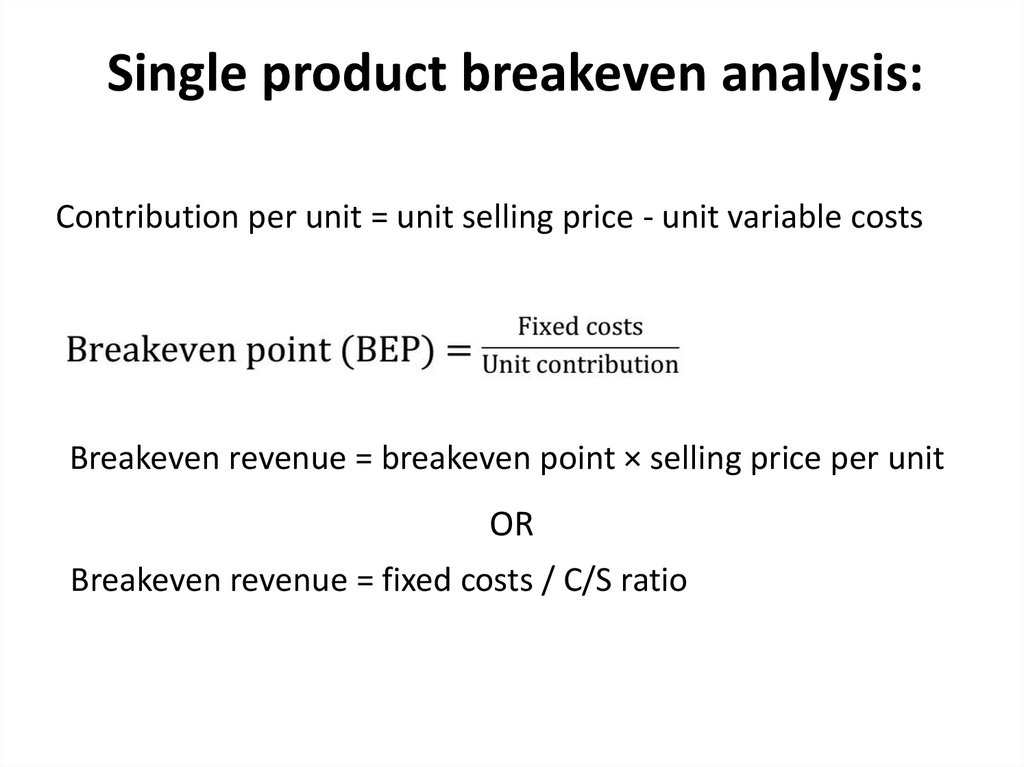

Single product breakeven analysis:Contribution per unit = unit selling price - unit variable costs

Breakeven revenue = breakeven point × selling price per unit

OR

Breakeven revenue = fixed costs / C/S ratio

22.

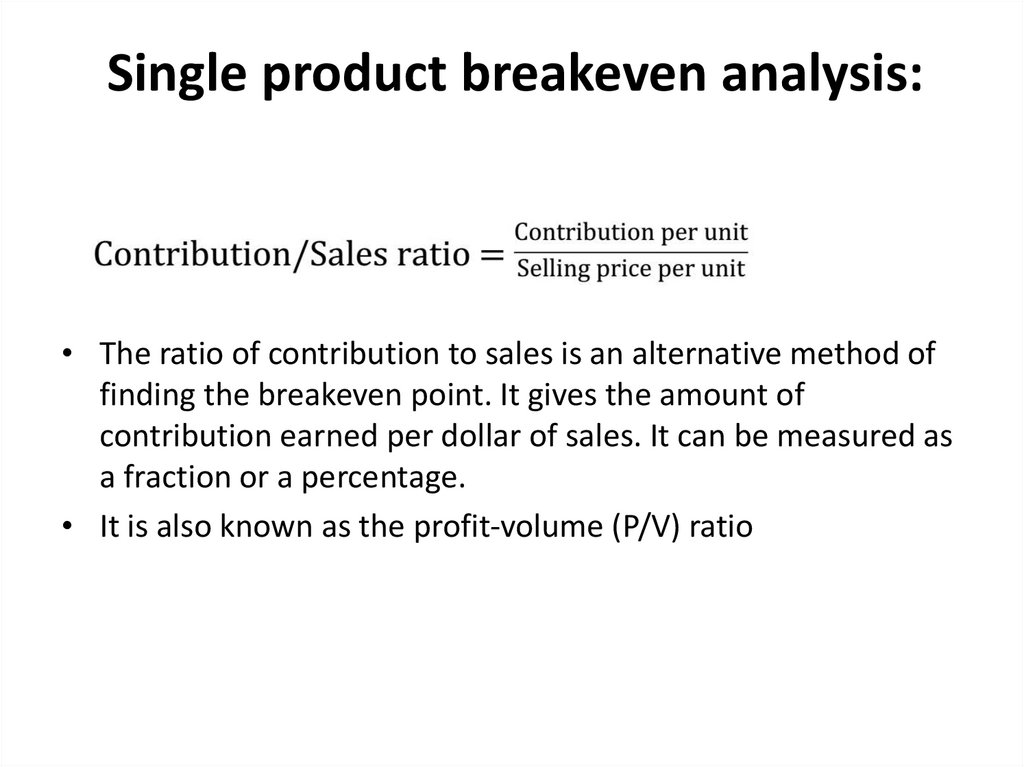

Single product breakeven analysis:• The ratio of contribution to sales is an alternative method of

finding the breakeven point. It gives the amount of

contribution earned per dollar of sales. It can be measured as

a fraction or a percentage.

• It is also known as the profit-volume (P/V) ratio

23.

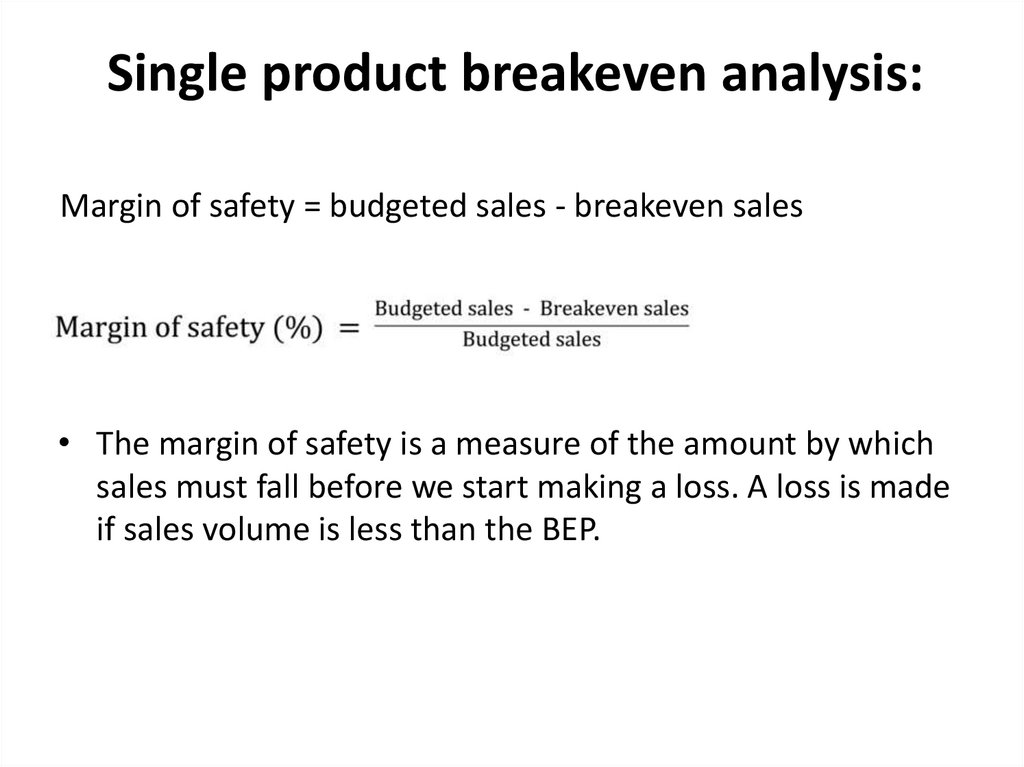

Single product breakeven analysis:Margin of safety = budgeted sales - breakeven sales

• The margin of safety is a measure of the amount by which

sales must fall before we start making a loss. A loss is made

if sales volume is less than the BEP.

24.

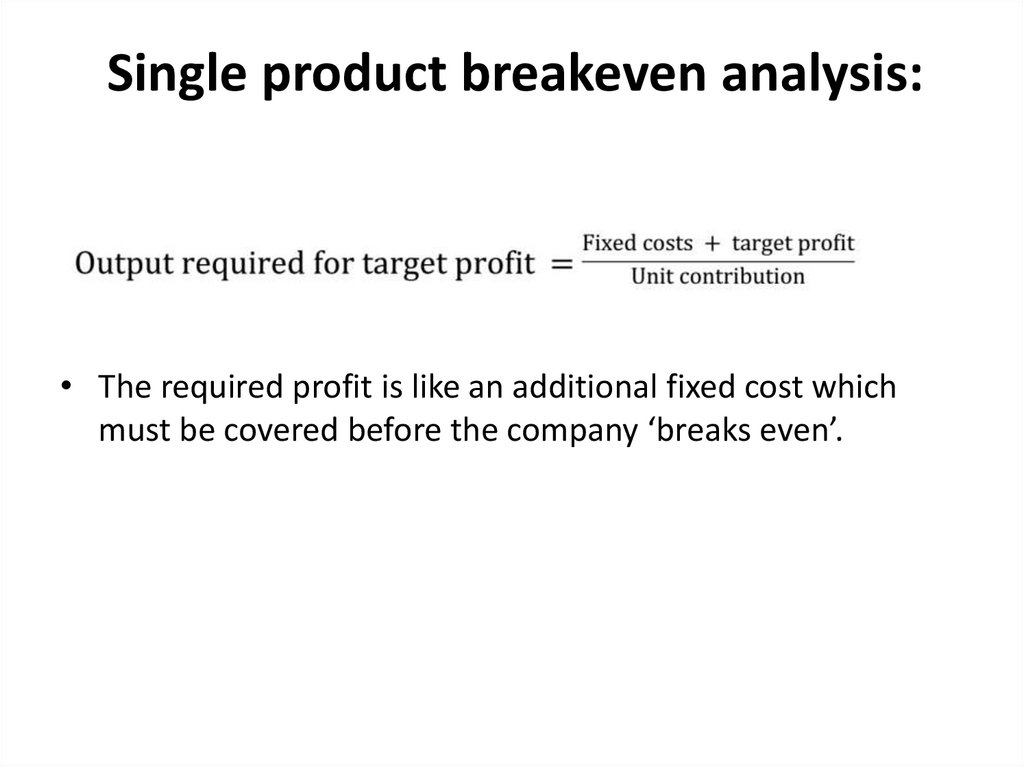

Single product breakeven analysis:• The required profit is like an additional fixed cost which

must be covered before the company ‘breaks even’.

25.

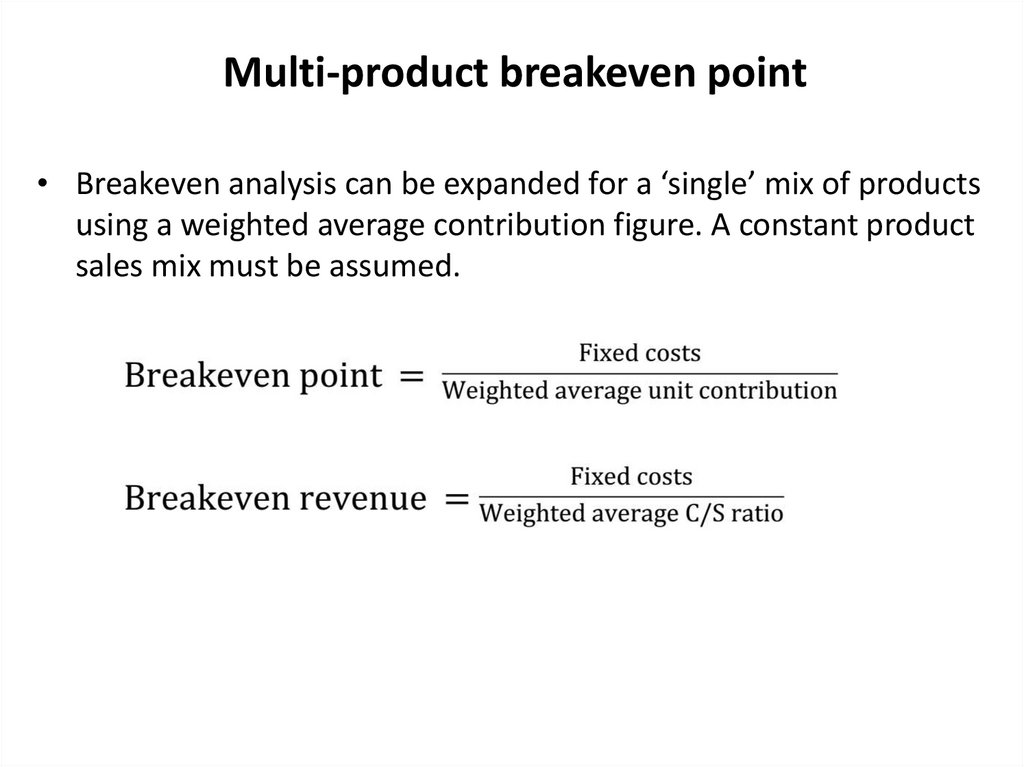

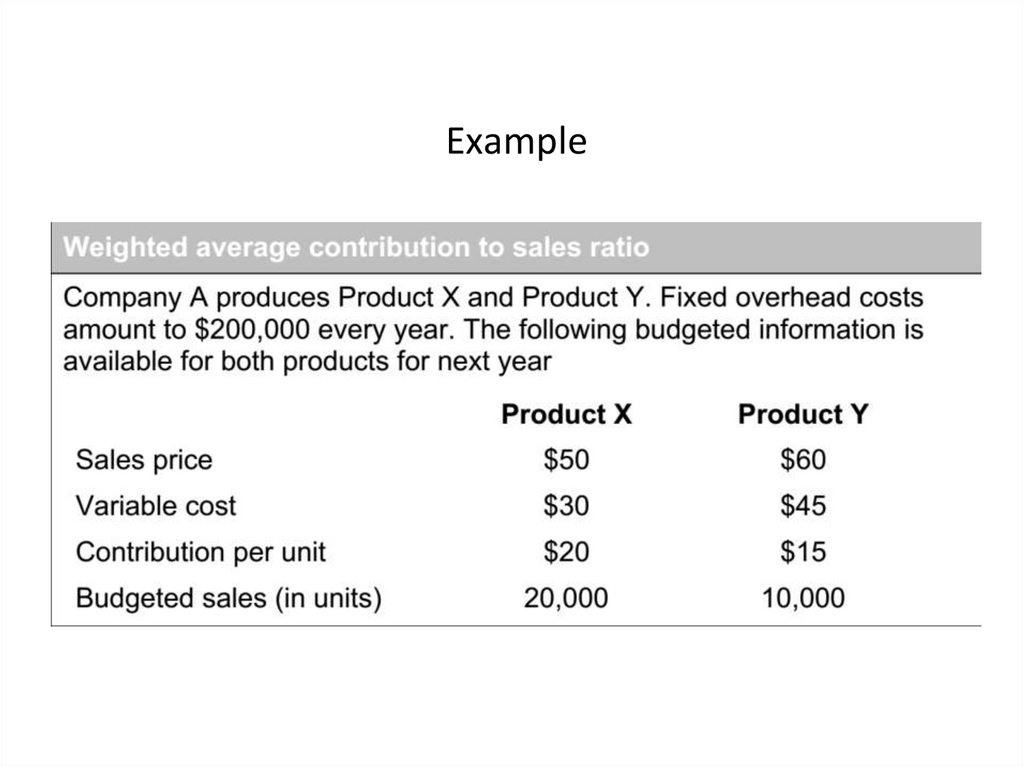

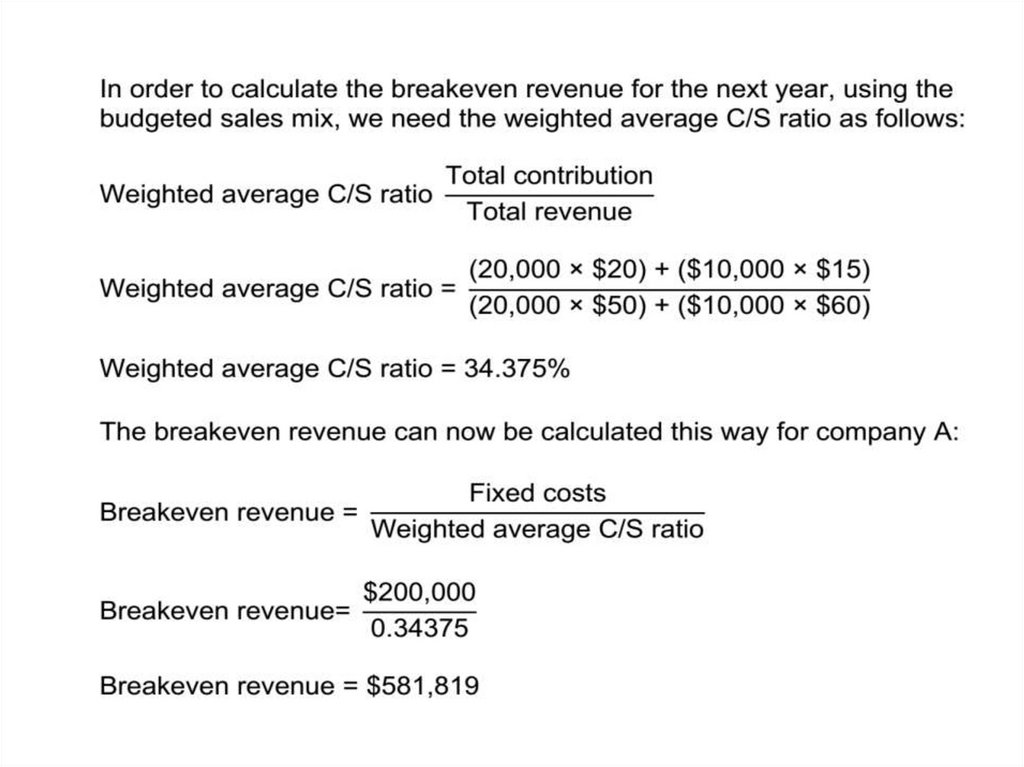

Multi-product breakeven point• Breakeven analysis can be expanded for a ‘single’ mix of products

using a weighted average contribution figure. A constant product

sales mix must be assumed.

26.

Example27.

28.

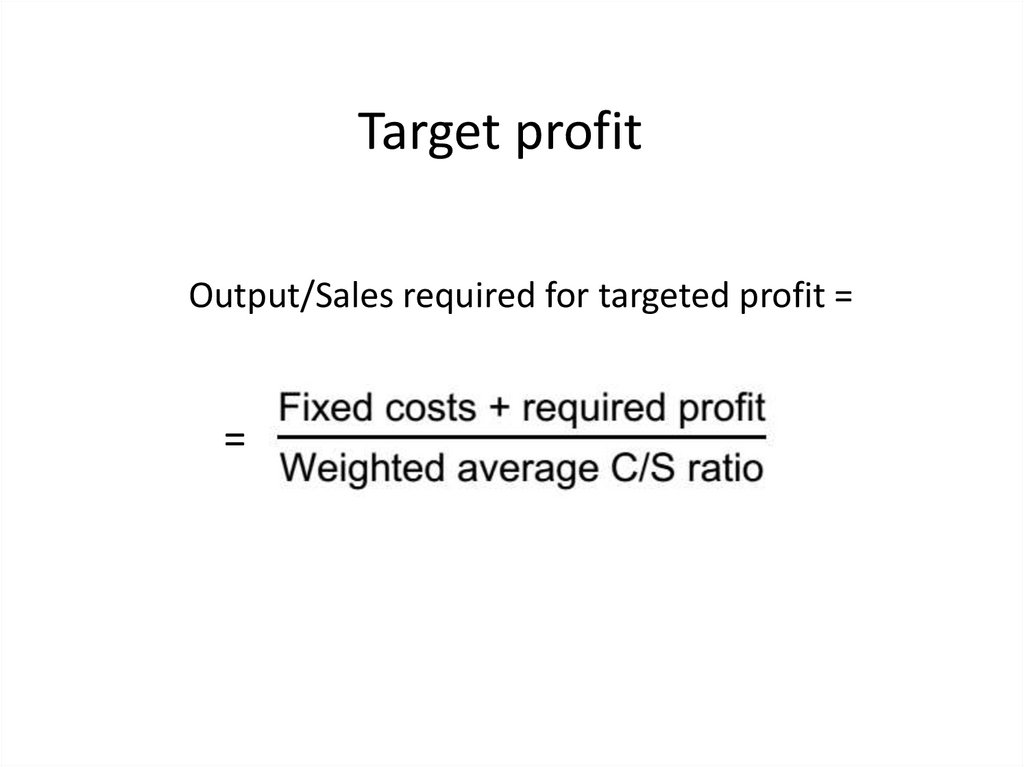

Target profitOutput/Sales required for targeted profit =

=

29.

Limiting factors andLinear programming

30.

Limiting factorsThe production and sales plans of a business may

be limited by a limiting factor/scarce resource.

This could be:

• Market demand

• Materials

• Manpower (labor)

• Machine hours

• Money

31.

Planning with one limiting factor• Options must be ranked using contribution earned per unit

of the scarce resource.

Steps in key factor analysis

If there is one limiting factor, then the problem is best solved

using key factor analysis:

• Step 1: Identify the scarce resource.

Step 2: Calculate the contribution per unit for each product.

• Step 3: Calculate the contribution per unit of the scarce

resource for each product.

• Step 4: Rank the products in order of the contribution per

unit of the scarce resource.

• Step 5: Allocate resources using this ranking and answer

the question.

32.

Linear programming - Planningwith several limiting factors

33.

Linear programming• Mathematical technique

• Applied to the problem of rationing limited

resources (factors) among many alternative

uses

• Seeks to find a feasible combination of output

that will maximize or minimize the objective

function.

• Objective function – maximizing profits

(contribution) or minimizing costs.

34.

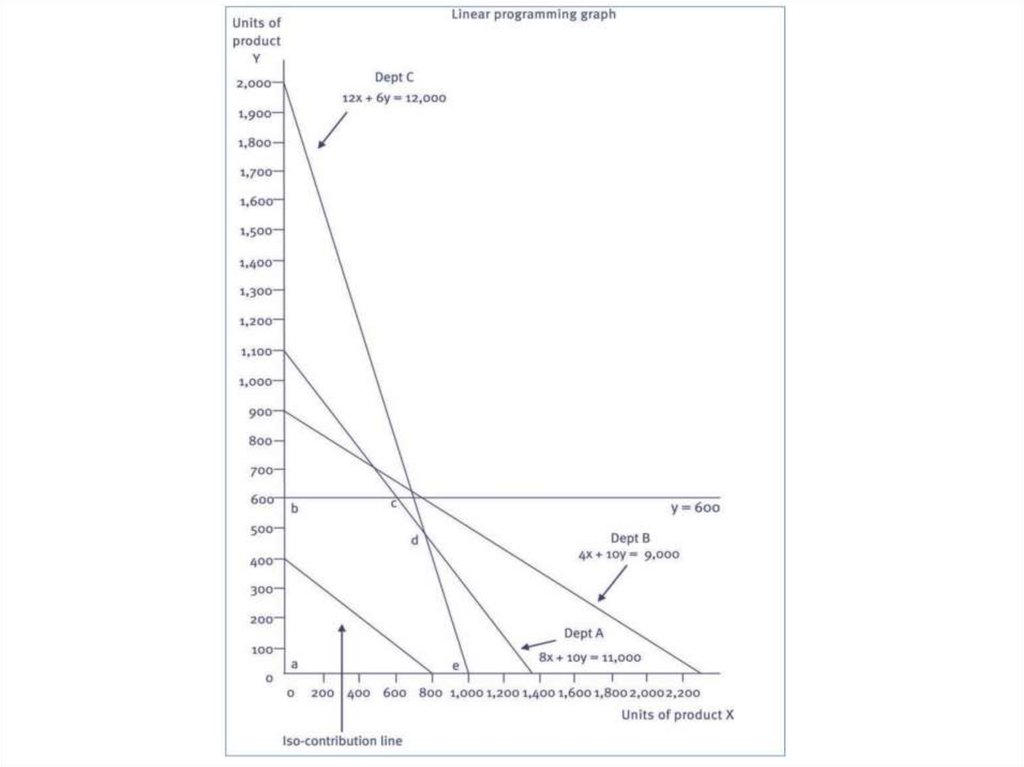

Linear programming steps:• Define the variables

• Set the objective function

• Identify the constraints

• Draw the graph with all the constraint

functions

• Determine the feasible region

• Find the optimum solution

35.

36.

Slack• When discussing constraints, slack is the amount

by which a resource is under-utilized, i.e. slack

occurs when the maximum availability of a

resource is not used. Graphically speaking, it will

occur when the optimum point does not fall on a

given resource line.

• The optimal solution will typically occur where

two ("critical") constraint lines cross. There will

be no slack for these constraints/resources as

they will be fully utilized. Hence, a shadow price

can be calculated.

37.

Slack• For other constraint lines, the fact that the optimal solution is not

on these lines means that the resources are not fully utilized, so

there will be slack.

Slack is important for two reasons:

• For critical constraints (zero slack), then gaining additional units of

these scarce resources will allow the optimal solution to be

improved (e.g. higher contribution earned). Similarly if another

department wants these resources then it will result in lower

contribution.

• For non-critical constraints, gaining or losing a small number of

units of the scarce resource will have no impact on the optimal

solution. To determine how much this makes scarce resources

worth to the business, see below on "shadow prices"

38.

Shadow priceThis is the ‘increase in value which would be created by

having available one additional unit of a limiting resource

at the original cost’. (CIMA Official Terminology)

A shadow price is:

• The additional contribution generated from one

additional unit of limiting factor.

• The opportunity cost of not having the use of one extra

unit of limiting factor.

• The maximum extra amount that should be paid for

one additional unit of scarce resource.

39.

Shadow price• The shadow price of a resource can be found by

calculating the increase in value (usually extra

contribution) which would be created by having

available one additional unit of a limiting resource at

its original cost.

• It therefore represents the maximum premium that the

firm should be willing to pay for one extra unit of each

constraint.

• Non-critical constraints will have zero shadow prices as

slack exists already.

40.

Shadow priceThe simplest way to calculate shadow prices for a critical constraint is

as follows:

• Step 1: Take the equations of the straight lines that intersect at the

optimal point. Add one unit to the constraint concerned, while

leaving the other critical constraint unchanged.

• Step 2: Use simultaneous equations to derive a new optimal

solution.

• Step 3: Calculate the revised optimal contribution and compare to

the original contribution calculated. The increase is the shadow

price.

41.

Divisional PerformanceMeasurement

42.

Divisional performance measuresCharacteristics of good divisional performance measures are

following:

• Goal congruence – measures should encourage divisional

managers to make decisions which are in the company’s best

interests overall

• Controllability – managers, and divisions, should only be

assessed in relation to aspects of performance they can

control

• Long-term and short-term – Recognize the long-term

objectives as well as short-term objectives of the organization

43.

Measures of divisional performance/profitability• Measuring managerial performance

–

Controllability principle applies: only those items directly controllable

by the manager should be included and uncontrollable costs

(depreciation on divisional assets and allocated central administrative

costs) should be excluded from the performance measure.

• Measuring divisional/economic performance

– Principle of separate independent entity applies: Performance measure

should include allocated central administrative costs, because if the

divisions were independent companies, they would have to incur all

these allocated central costs such as interest expenses.

44.

Difference between controllable, traceable costs andallocated head office costs

• Controllable costs are those which are controllable by the manager of the

division.

Sales revenues – Controllable costs = Controllable profit

• Traceable costs include controllable costs plus other costs (avoidable)

directly attributable to a division, but which the manager doesn’t control.

Controllable profit – Traceable costs (Divisional costs not

controlled by divisional manager) = Traceable profit

• Allocated head office costs are costs incurred centrally (to all or many

divisions) and then re-apportioned to a division.

• Traceable profit - Allocated head office costs = Divisional (net) profit

(before taxes)

45.

Measures of divisional performance (ROI)• Return on investment (ROI): measures operating profit after

deducting depreciation charges as a percentage of the assets

employed in the division. ROI needs to be greater than the cost of

capital for a division to be profitable in the long term.

• ROI (%) = Traceable (controllable*) profit / Traceable

(controllable*) investment **

* If manager’s performance is being assessed, rather than the

division’s, ROI should be based on ‘controllable’ figures, not ‘traceable’

ones.

** Capital Employed, which is = total assets minus current liabilities (or

equity + long-term debt). If manager’s performance is being assessed

then divisional net controllable assets should be considered.

46.

Measures of divisional performance (RI)• Residual income (RI): the income (net of depreciation on

non-current assets) that the division is earning less cost of

capital charge (imputed interest) on the assets employed in

the division.

• RI = Traceable (controllable) profit – imputed interest* on

traceable (controllable) investment

* Imputed interest is calculated by multiplying the traceable (or

controllable) investment by the cost of capital. This is typically

the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). However, instead

of using WACC, a company might also set a target rate of return

on the capital provided. In such a situation, a positive RI will

indicate a division is generating a level of return greater than

the target.

47.

Transfer pricing and BSC48.

Goals of transfer pricingThe price charged should ensure that the transfer satisfies

the company, the supplying division and the receiving

division.

It is vital that the transfer price is carefully selected to

ensure all parties act in the best interest of the company.

The goals of a transfer pricing system are:

• (a) Goal congruence

• (b) Equitable performance measurement

• (c) Retained divisional autonomy

• (d) Motivated divisional managers

• (e) Optimum resource allocation

49.

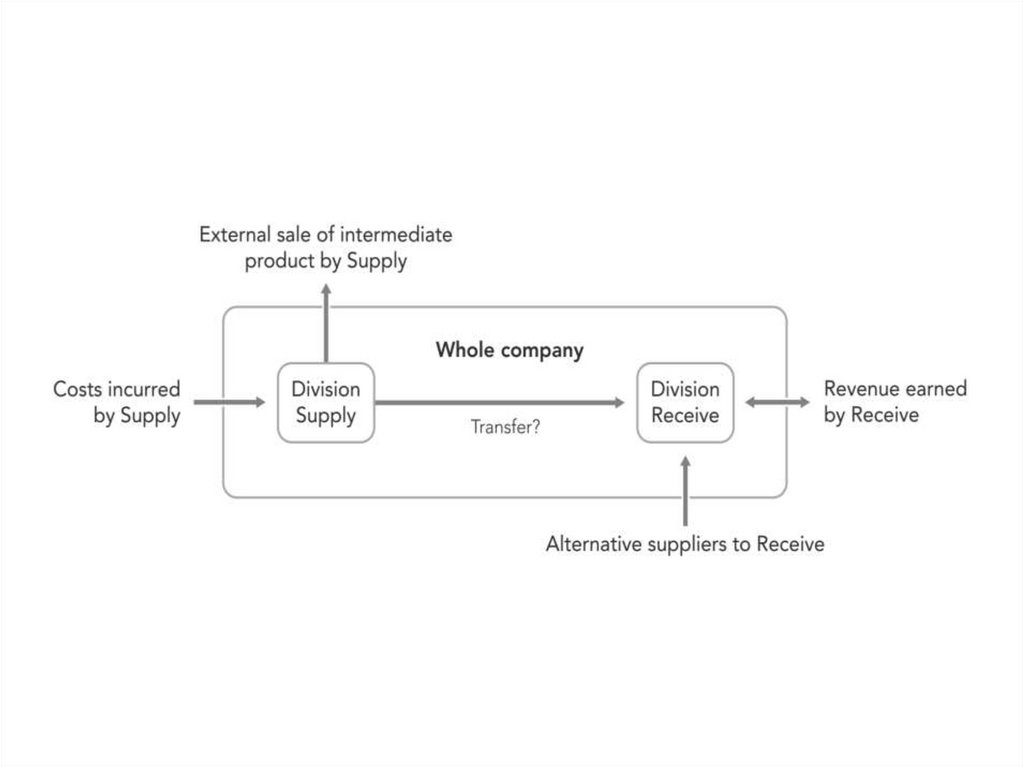

50.

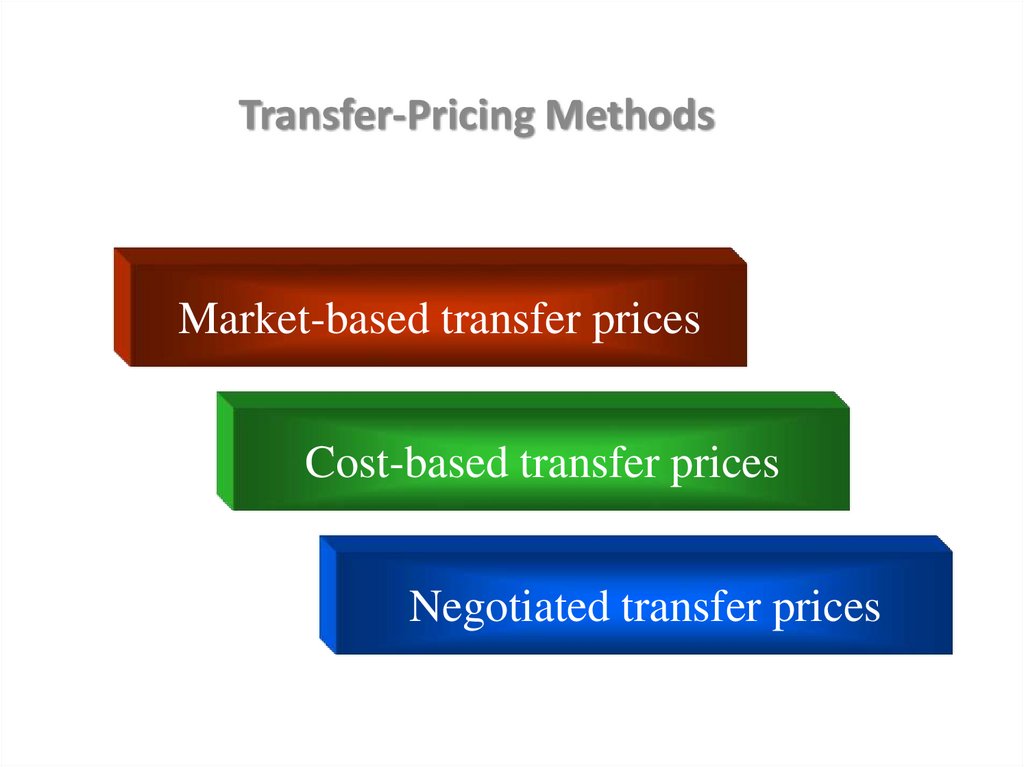

Transfer-Pricing MethodsMarket-based transfer prices

Cost-based transfer prices

Negotiated transfer prices

51.

Market based transfer pricing• Divisional autonomy

– Division A has the freedom to sell on the open market, or with B

– Simply B can decide whether to buy from the open market or

from A

– So autonomy is good using a market based transfer price

• Corporate Profit Maximization

– Using market price, strangely you can still expect B to buy from

A - as there should be a better quality of service, greater

flexibility, and dependability of supply.

– Division A will more likely sell to B than the open market due to

cheaper costs of administration, selling and transport.

– A market price as the transfer price would therefore result in

decisions which would be in the best interests of the group as a

whole.

52.

Marginal cost-based transfer pricing• Division A charges its variable costs only to B

• This means though, it does not cover its fixed costs - and so is

demotivating for Division A - although it's great for Division B!

• A has no incentive either to keep its variable costs low

• HOWEVER - it does mean B will get all it's products from A and this will lead to goal congruence as their MC will be the

same as the group as a whole

53.

Full cost-based transfer pricing• Division A charges the full cost (including fixed overheads

absorbed).

• They would still not earn any profit - so sometimes a COST + profit

approach is used. If a full cost plus approach is used, a profit margin

is also included in this transfer price.

• Division A gets some profit at the expense of Division B.

• However, Division A has no incentive to keep costs down -although

using standard costs instead of actual costs would prevent this.

• Also, Division B's variable costs include Division A's FC and profit this can lead to dysfunctional decisions

54.

Negotiated Transfer Pricing• In some cases, the divisions of a company are free to

negotiate the transfer price between themselves and

then to decide whether to buy and sell internally or

deal with outside parties.

• Negotiated transfer prices are often employed when

market prices are volatile and change occurs

constantly.

• The negotiated transfer price is the outcome of a

bargaining process between the supplying and

receiving division.

55.

Other Approaches to Transfer PricingThere are two approaches to transfer pricing which try to preserve the economic

information inherent in variable costs while permitting the transferring division

to make profits and allowing better performance valuation:

• Variable cost plus lump sum (“two-part” tariff transfer pricing system):

Here transfers are made at variable cost but, periodically, a transfer is made

between the two divisions to account for A's fixed costs and profit (supplying

division charges the receiving division a fixed fee to recover its fixed costs and earn a

profit).

• Dual Pricing:

Here, Division A transfers out at cost plus a mark up and the receiving division

transfers in at variable cost.

Obviously, the divisional current accounts won’t agree, and some period-end

adjustments will be needed to reconcile those and eliminate fictitious interdivisional

profits.

56.

Minimum and Maximum Transfer Prices• What is the minimum selling price that the selling division

would be prepared to sell for?

• What is the maximum price that the buying division would be

prepared to pay for the product?

57.

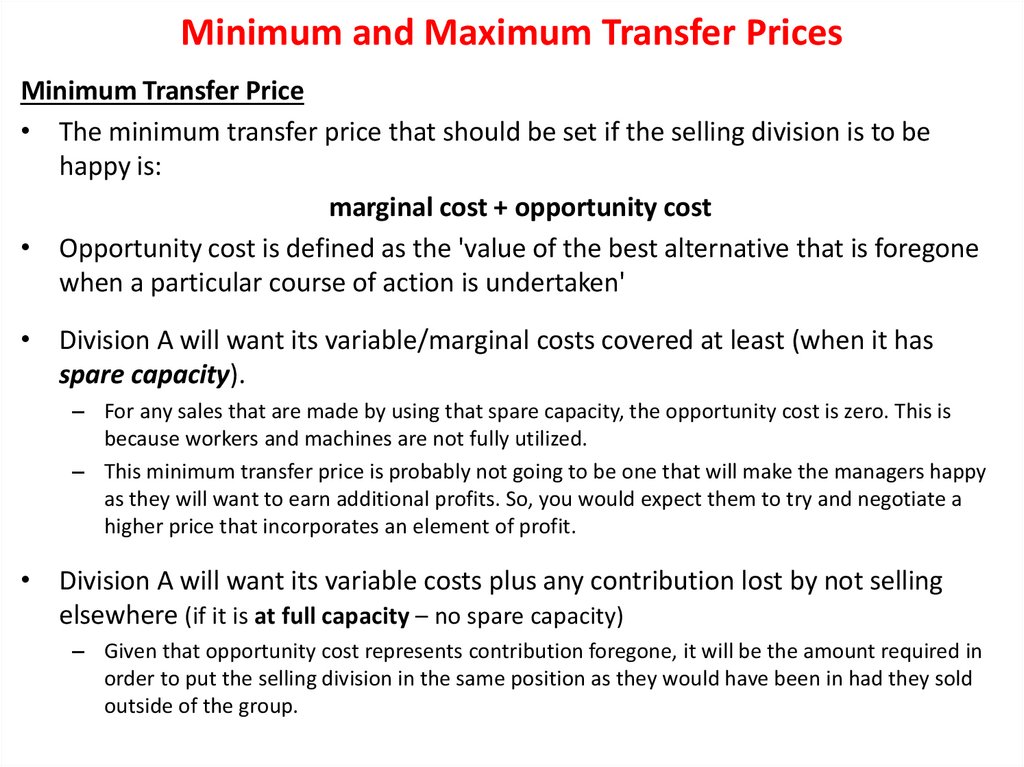

Minimum and Maximum Transfer PricesMinimum Transfer Price

• The minimum transfer price that should be set if the selling division is to be

happy is:

marginal cost + opportunity cost

• Opportunity cost is defined as the 'value of the best alternative that is foregone

when a particular course of action is undertaken'

• Division A will want its variable/marginal costs covered at least (when it has

spare capacity).

– For any sales that are made by using that spare capacity, the opportunity cost is zero. This is

because workers and machines are not fully utilized.

– This minimum transfer price is probably not going to be one that will make the managers happy

as they will want to earn additional profits. So, you would expect them to try and negotiate a

higher price that incorporates an element of profit.

• Division A will want its variable costs plus any contribution lost by not selling

elsewhere (if it is at full capacity – no spare capacity)

– Given that opportunity cost represents contribution foregone, it will be the amount required in

order to put the selling division in the same position as they would have been in had they sold

outside of the group.

58.

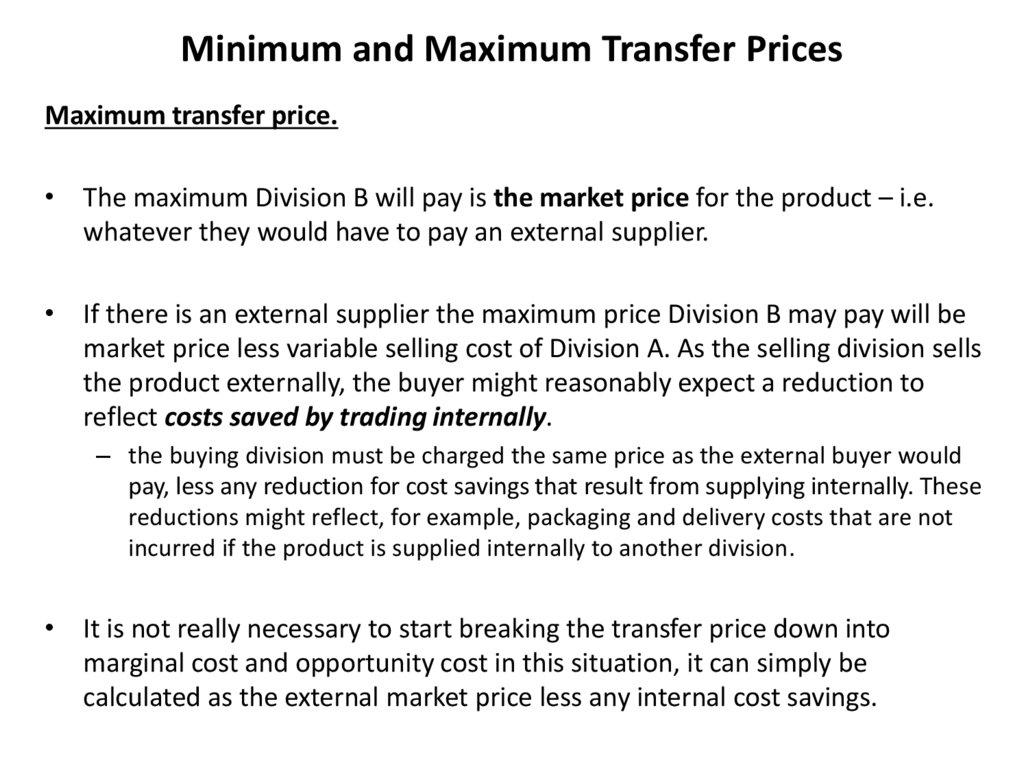

Minimum and Maximum Transfer PricesMaximum transfer price.

• The maximum Division B will pay is the market price for the product – i.e.

whatever they would have to pay an external supplier.

• If there is an external supplier the maximum price Division B may pay will be

market price less variable selling cost of Division A. As the selling division sells

the product externally, the buyer might reasonably expect a reduction to

reflect costs saved by trading internally.

– the buying division must be charged the same price as the external buyer would

pay, less any reduction for cost savings that result from supplying internally. These

reductions might reflect, for example, packaging and delivery costs that are not

incurred if the product is supplied internally to another division.

• It is not really necessary to start breaking the transfer price down into

marginal cost and opportunity cost in this situation, it can simply be

calculated as the external market price less any internal cost savings.

59.

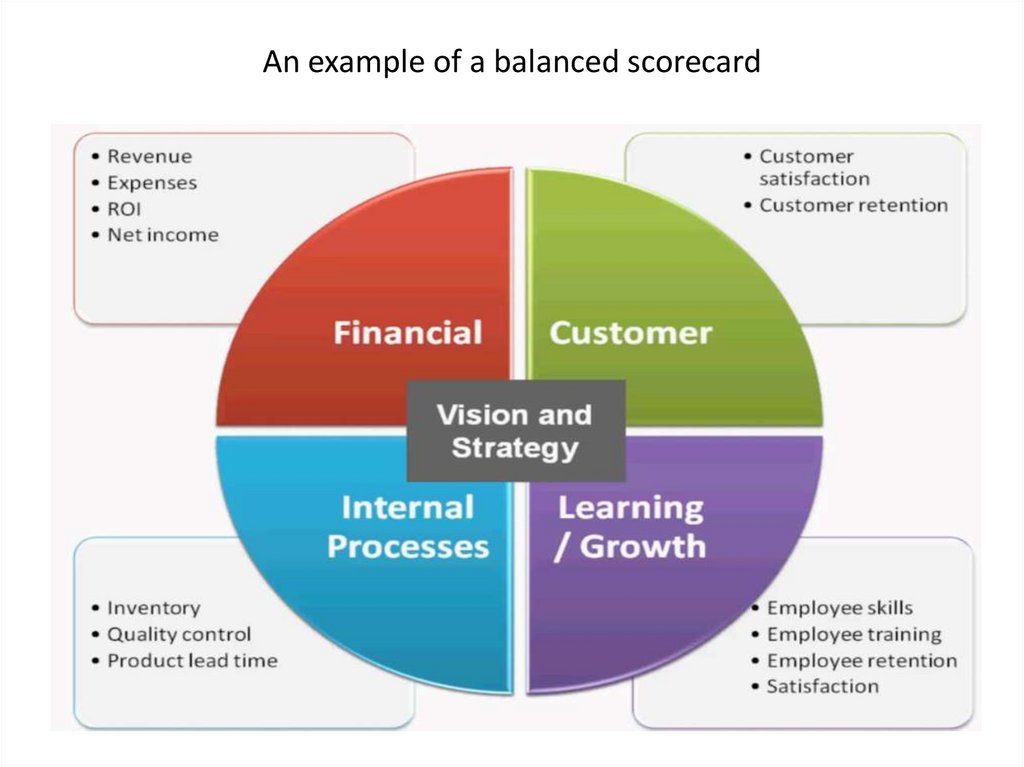

Balanced Score Card60.

Four perspectives of BSC:• The balanced scorecard approach to performance measurement and

control emphasizes the need to provide management with a set of

information which covers all relevant areas of performance.

• It focuses on four different perspectives and uses financial and nonfinancial indicators.

• The four perspectives are:

• Customer – what is it about us that new and existing customers value?

• Internal – what processes must we excel at to achieve our financial and

customer objectives?

• Innovation and growth (learning) – how can we continue to improve and

create future value?

• Financial – how do we create value for our shareholders?

• Within each of these perspectives a company should seek to identify a

series of goals and measures.

Финансы

Финансы