Похожие презентации:

History of Anglo-Saxon Tribes. Lecture 1

1. Lecture 1. History of Anglo-Saxon Tribes

Lecture 1. History of AngloSaxon TribesLectures in the History of the English language (prof. Igor V. Chekulai).

Chekulai 2023©

2. Problems viewed in the Lecture

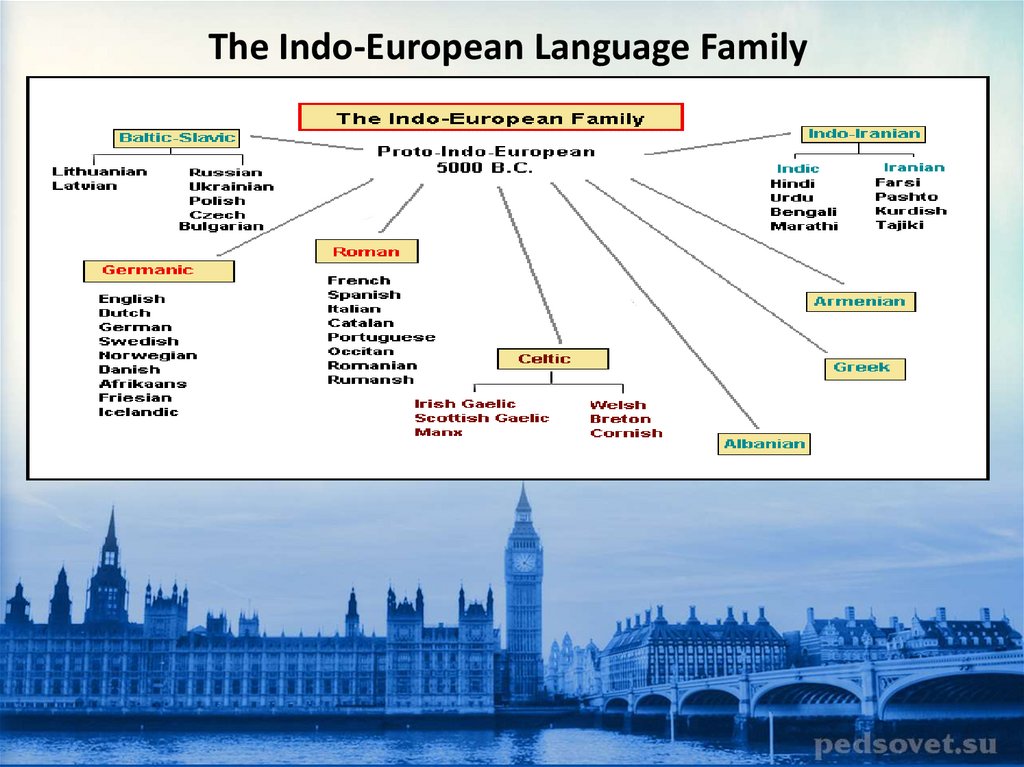

1. The place of the Germanic tribes within the Indo-Europeanlanguage family.

2. The ancient Germanic tribes, their social and ethnic peculiarities.

3. The sub-groups of the Germanic tribes and their linguistic

classification.

4. The Ingaevones on the British Isles: their prehistory and the

invasion on the island.

5. The history of England before and during the Norman Conquest.

3. Preface

A language family is agroup of languages

related through descent

from a common ancestral

language or parental

language, called the

proto-language of that

family.

Linguists therefore

describe the daughter

languages within a

language family as

being genetically related

4. The Indo-European Language Family

5.

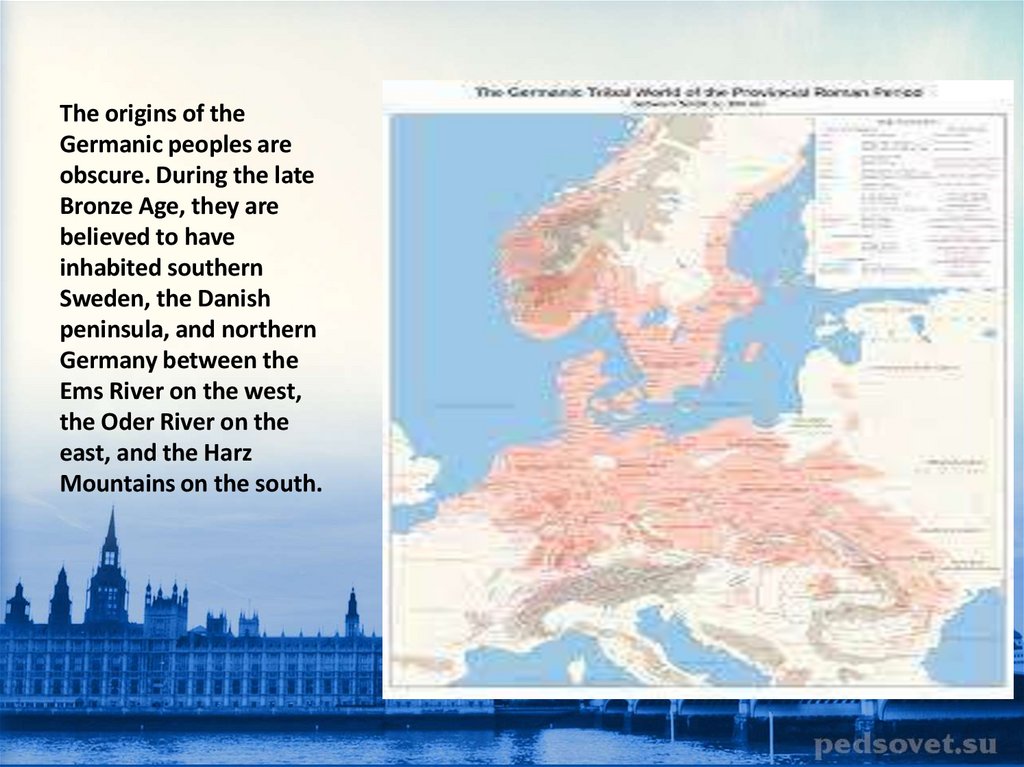

The origins of theGermanic peoples are

obscure. During the late

Bronze Age, they are

believed to have

inhabited southern

Sweden, the Danish

peninsula, and northern

Germany between the

Ems River on the west,

the Oder River on the

east, and the Harz

Mountains on the south.

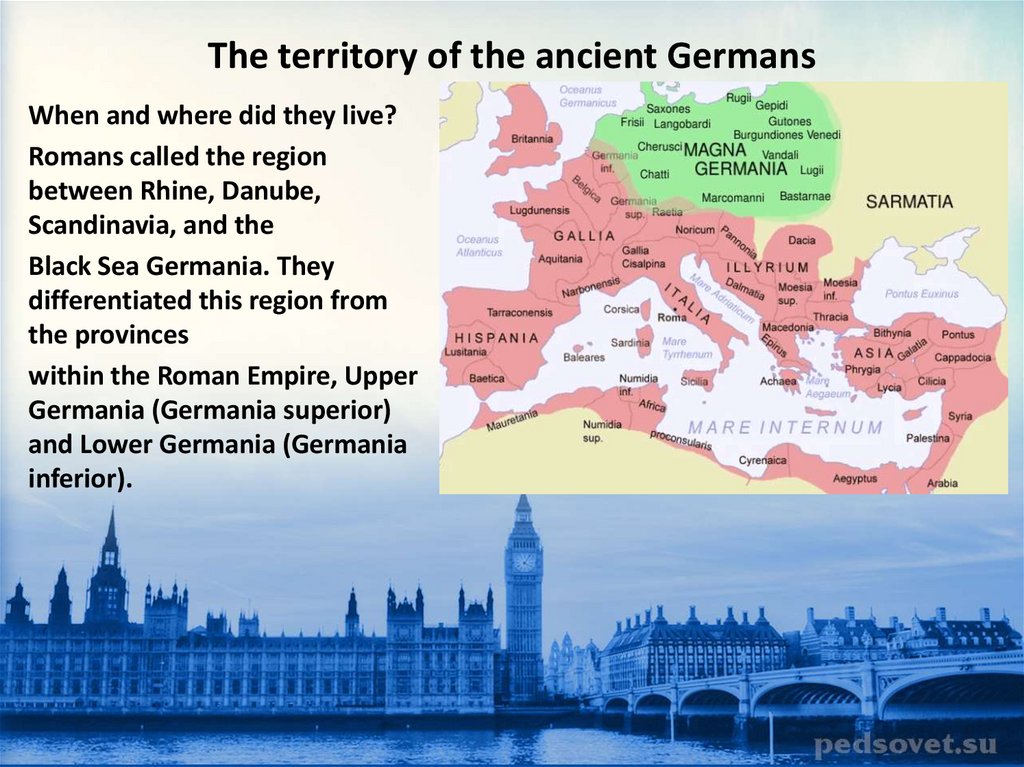

6. The territory of the ancient Germans

When and where did they live?Romans called the region

between Rhine, Danube,

Scandinavia, and the

Black Sea Germania. They

differentiated this region from

the provinces

within the Roman Empire, Upper

Germania (Germania superior)

and Lower Germania (Germania

inferior).

7. Crafts and Professions in the Germanic tribes

How did Germanic tribes live?Most Germanic peoples lived in settlements with up to 20 farmsteads.

These farms consisted of longhouses, in which people and animals lived

together, as well as granaries and workshops. Feddersen Wierde, a site

in present-day Lower Saxony, is the settlement in which archaeologists

have found the most and best-preserved remains. Houses were built of

wood and clay. These materials do not mean that the houses were inferior to the

stone houses that were built in the Roman Empire, they were

simply adapted to a way of life and climate. It is possible that several

families lived under one roof.

Germanic settlements grew and produced almost everything that their

inhabitants needed to live. Archaeologists refer to Germanic tribes as

cattle farmers, which means that they grew grain and vegetables and

kept animals for their meat and skins. Tools, clothing, and vessels were

made on site by craftsmen.

8. The nation of warriors

Against whom did Germanic tribes fight?Archaeologists have found many weapons in what

the Romans called Germania. Warriors seem to

have been well equipped: they had lances, spears,

swords and round shields. Different groups often

fought each other. Sometimes they joined forces to

fend off attacks by the Roman army or to raid

outposts of the Roman Empire together. These

fights were well organized. Germanic tribes fought

against Romans, for example, at Kalkriese, in a

battle that came to be known as the Varusschlacht,

or at a place in Lower Saxony called Harzhorn.

9. Germanic gods

It is very difficult to find out what Germanic tribesbelieved. We only have Roman accounts that

have described the religious acts of Germanic

tribes, and we can’t be sure that what the

Romans wrote was actually what occurred. In

addition to these written sources, there are

archaeological finds that may have to do with cult

and religion. It is likely that there was no one,

standardized Germanic religion, but possibly

Germanic tribes offered sacrifices to their gods by

sinking valuable objects into bogs and lakes.

You may have heard of the gods Odin or Thor and

thought they were Germanic gods. But no one

can know that for a fact today. The names of

these gods appear for the first time in a text from

the 13th century called the Edda.

Sunday – “the day of the Sun”

Monday –”the day of the Moon”

Tuesday – “the day of Tues”

Wednesday – “the day of Wotan”

Thursday – “the day of Thor”

Friday – “the day of Freia”

Saturday – “the day of Saturn”

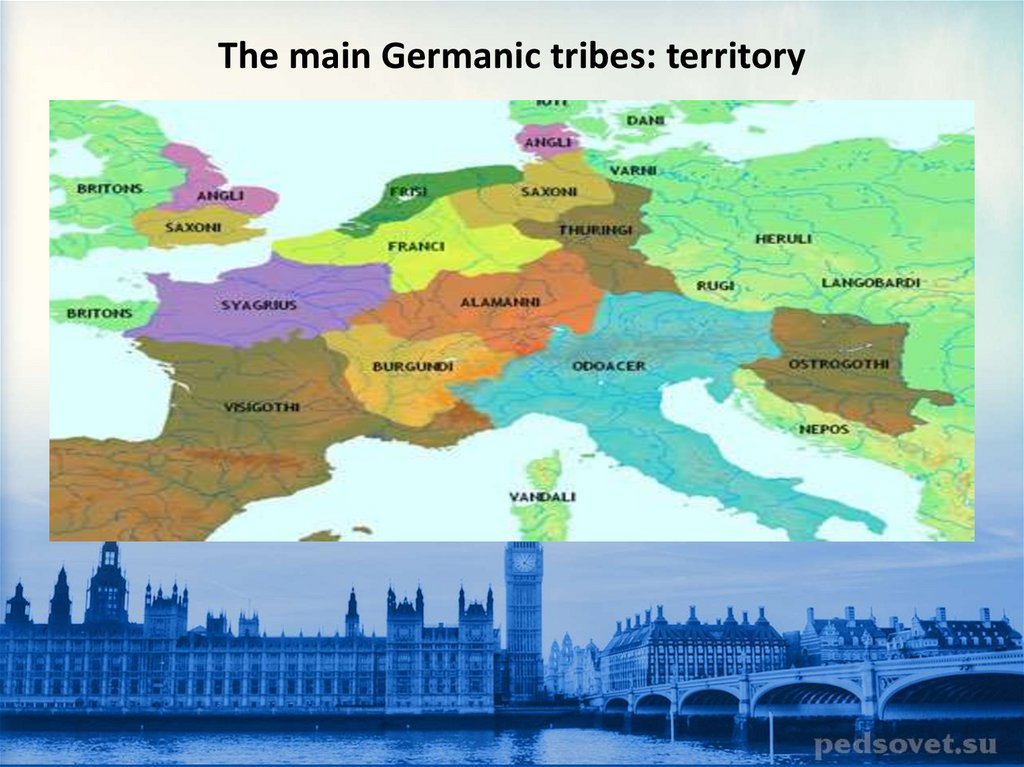

10. The main Germanic tribes: territory

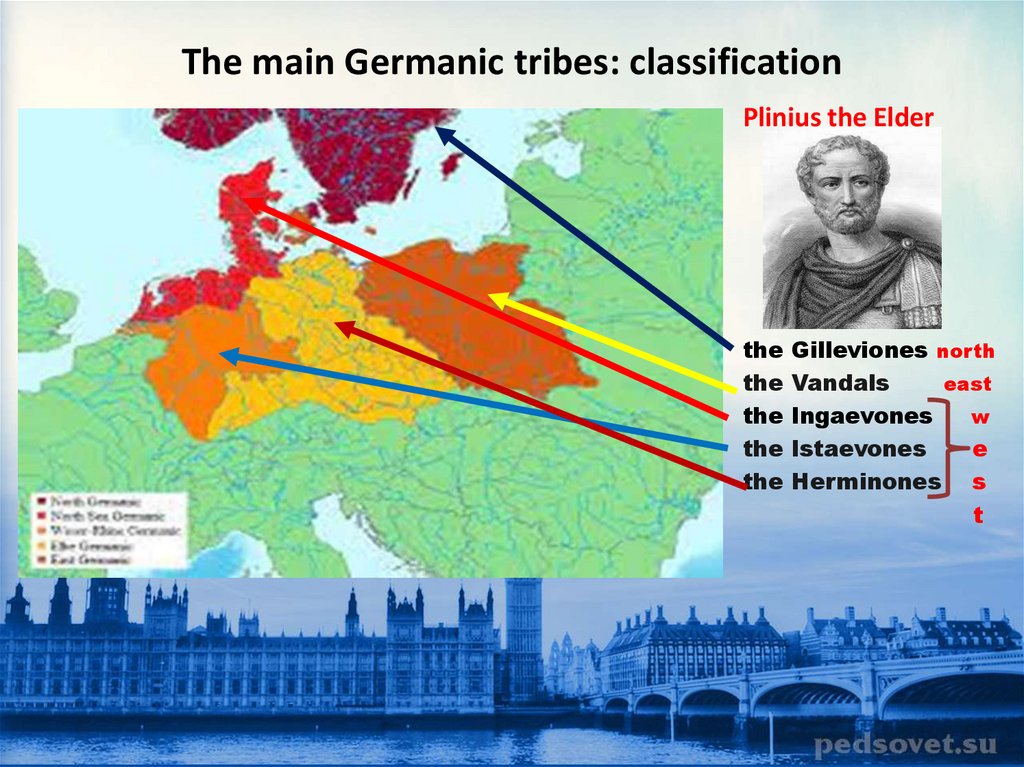

11. The main Germanic tribes: classification

Plinius the Elderthe Gilleviones north

the Vandals

east

the Ingaevones

w

the Istaevones

e

the Herminones s

t

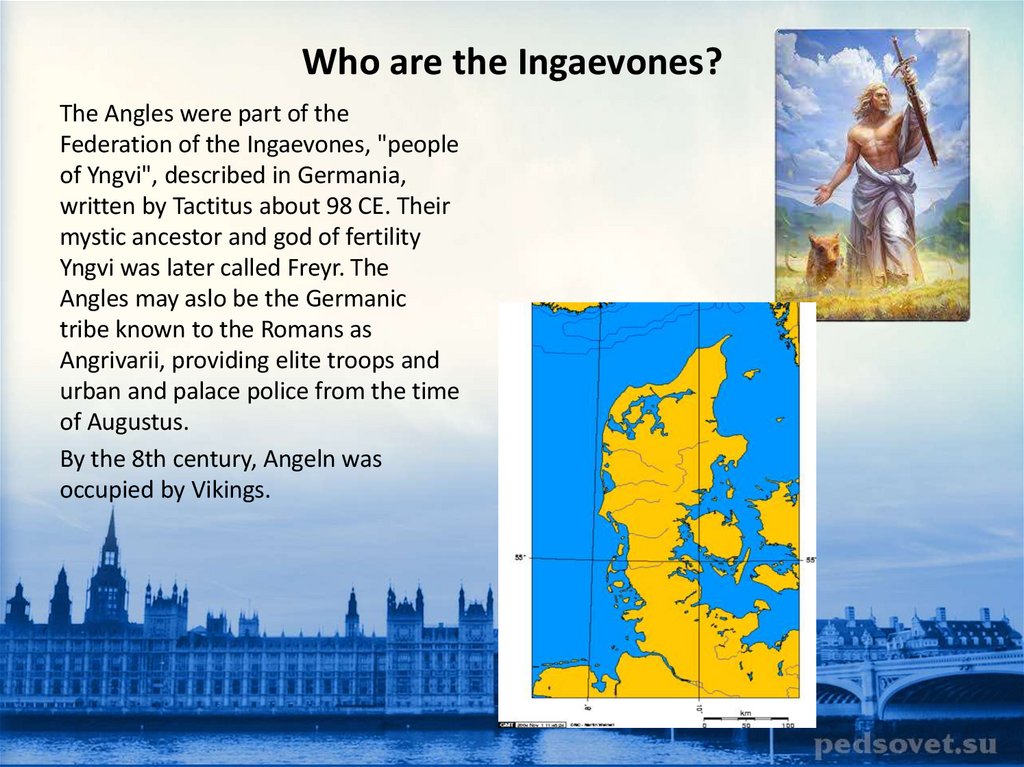

12. Who are the Ingaevones?

The Angles were part of theFederation of the Ingaevones, "people

of Yngvi", described in Germania,

written by Tactitus about 98 CE. Their

mystic ancestor and god of fertility

Yngvi was later called Freyr. The

Angles may aslo be the Germanic

tribe known to the Romans as

Angrivarii, providing elite troops and

urban and palace police from the time

of Augustus.

By the 8th century, Angeln was

occupied by Vikings.

13. The Anglo-Saxon Conquest of Great Britain (1)

According to the Anglo SaxonChronicle, between 449 and

455 Angles settled in Britian.

"From Anglia, which has ever

since remained waste

between the Jutes and the

Saxons, came the East

Angles, the Middle Angles,

the Mercians, and all of those

north of the Humber."

In the Anglo Saxon

Chronicles, Freawine

(Frowinus, Frowin) was the

governor of Schleswig from

whom the royal family of

Wessex claimed descent.

14. The Anglo-Saxon Conquest of Great Britain (2)

Hengist and Horsa are Germanic brotherssaid to have led

the Angles, Saxons and Jutes in their

invasion of Britain in the 5th century.

Tradition lists Hengist as the first of the

Jutish kings of Kent.

According to early sources, Hengist and

Horsa arrived in Britain at Ebbsfleet on

the Isle of Thanet. For a time, they served as

mercenaries for Vortigern, King of the

Britons, but later they turned against him

(British accounts have them betraying him).

Horsa was killed fighting the Britons, but

Hengist successfully conquered Kent,

becoming the forefather of its kings.

15. The early British kingdoms

16. The main historic events between the 5th and 11th centuries (1)

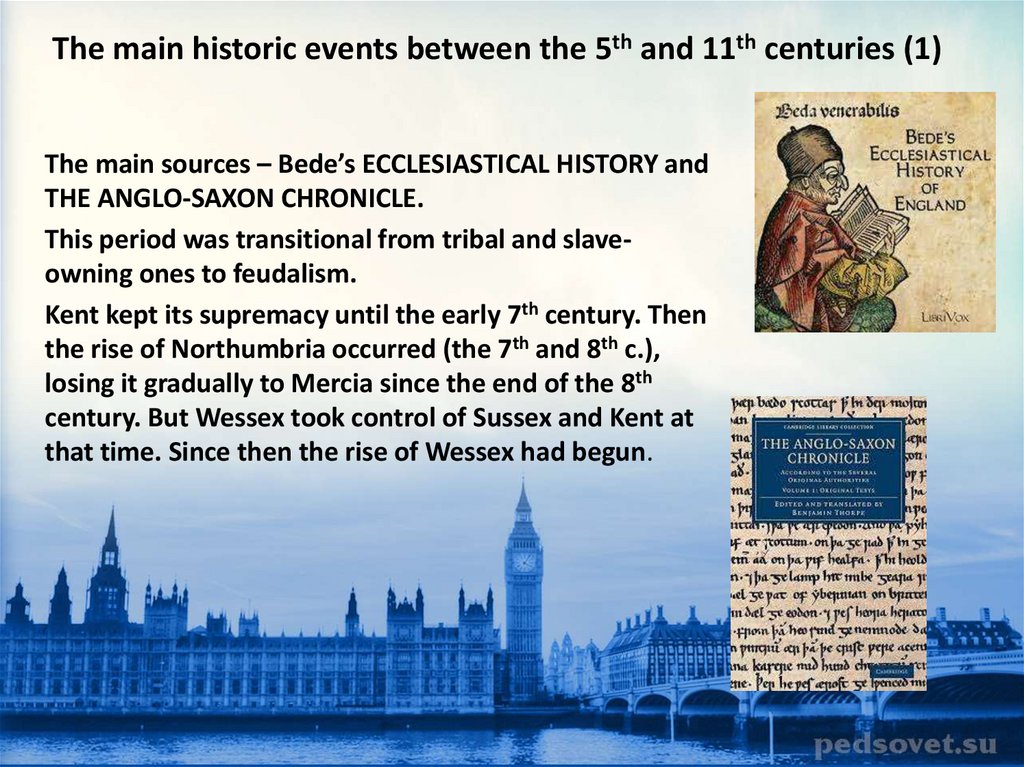

The main sources – Bede’s ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY andTHE ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLE.

This period was transitional from tribal and slaveowning ones to feudalism.

Kent kept its supremacy until the early 7th century. Then

the rise of Northumbria occurred (the 7th and 8th c.),

losing it gradually to Mercia since the end of the 8th

century. But Wessex took control of Sussex and Kent at

that time. Since then the rise of Wessex had begun.

17. The main historic events between the 5th and 11th centuries (1)

The kingdoms of Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria and East Anglia each still possessed their owndynasty; smaller kingdoms remained important as internal components of these larger polities,

but no longer had the capacity for independent political action (for the case of Essex at this time,

see Yorke 1985, 24, 36).

The status quo between the four main kingdoms was relatively stable during this period following

a brief but tumultuous phase of warfare between Wessex and Mercia in the 820s. It was these

military successes that established Wessex as a serious challenger to Mercian hegemony in

southern England (Keynes 1995, 39–41). Ecgberht's victory in 825 brought the south-east of

England (Essex, Surrey, Sussex and Kent) under West Saxon control, and these territories were to

remain important components of the West Saxon kingdom, more integrated into the workings of

royal government than they had been under Mercian overlordship (Keynes 1993). Another

campaign against Mercia in 829 made Ecgberht king of the Mercians (as well as the West Saxons)

for a year, and he traversed the kingdom to meet with the ruler of the Northumbrians at Dore,

South Yorkshire, as well. This action later prompted the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to acclaim

Ecgberht as the eighth in a line of kings with dominion over all England south of the Humber,

temporary though his supremacy was: Wiglaf, former king of the Mercians, regained the throne

the following year (827–9, 830–40). After 830 there is no further evidence of direct conflict

between the English kingdoms.

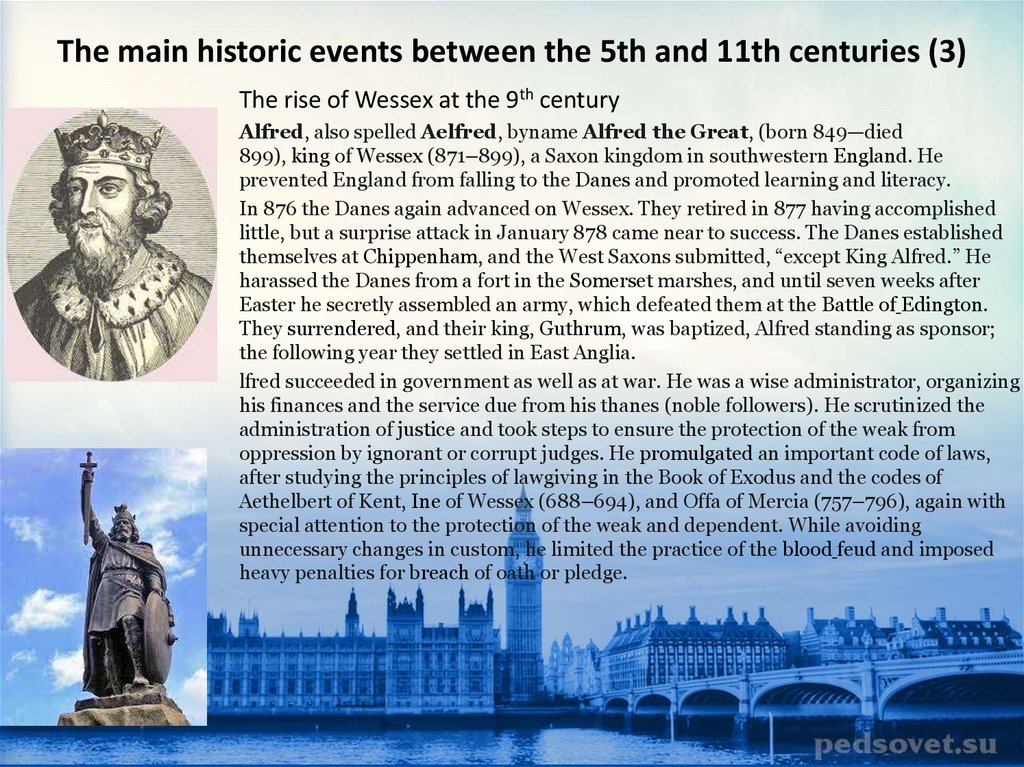

18. The main historic events between the 5th and 11th centuries (3)

The rise of Wessex at the 9th centuryAlfred, also spelled Aelfred, byname Alfred the Great, (born 849—died

899), king of Wessex (871–899), a Saxon kingdom in southwestern England. He

prevented England from falling to the Danes and promoted learning and literacy.

In 876 the Danes again advanced on Wessex. They retired in 877 having accomplished

little, but a surprise attack in January 878 came near to success. The Danes established

themselves at Chippenham, and the West Saxons submitted, “except King Alfred.” He

harassed the Danes from a fort in the Somerset marshes, and until seven weeks after

Easter he secretly assembled an army, which defeated them at the Battle of Edington.

They surrendered, and their king, Guthrum, was baptized, Alfred standing as sponsor;

the following year they settled in East Anglia.

lfred succeeded in government as well as at war. He was a wise administrator, organizing

his finances and the service due from his thanes (noble followers). He scrutinized the

administration of justice and took steps to ensure the protection of the weak from

oppression by ignorant or corrupt judges. He promulgated an important code of laws,

after studying the principles of lawgiving in the Book of Exodus and the codes of

Aethelbert of Kent, Ine of Wessex (688–694), and Offa of Mercia (757–796), again with

special attention to the protection of the weak and dependent. While avoiding

unnecessary changes in custom, he limited the practice of the blood feud and imposed

heavy penalties for breach of oath or pledge.

19. The Scandinavian invasion (the 9th- 11th centuries) (1)

In 793 came the first recorded Viking raid, where 'on the Ides of June the harrying ofthe heathen destroyed God's church on Lindisfarne, bringing ruin and slaughter' (The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle).

These ruthless pirates continued to make regular raids around the coasts of England,

looting treasure and other goods, and capturing people as slaves. Monasteries were

often targeted, for their precious silver or gold chalices, plates, bowls and crucifixes.

Gradually, the Viking raiders began to stay, first in winter camps, then settling in land

they had seized, mainly in the east and north of England. See The Vikings settle down.

Outside Anglo-Saxon England, to the north of Britain, the Vikings took over and settled

Iceland, the Faroes and Orkney, becoming farmers and fishermen, and sometimes

going on summer trading or raiding voyages. Orkney became powerful, and from

there the Earls of Orkney ruled most of Scotland. To this day, especially on the northeast coast, many Scots still bear Viking names.

20. The Scandinavian invasion (the 9th- 11th centuries) (2)

To the west of Britain, the Isle of Man became a Viking kingdom. The island still has itsTynwald, or ting-vollr (assembly field), a reminder of Viking rule. In Ireland, the Vikings

raided around the coasts and up the rivers. They founded the cities of Dublin, Cork

and Limerick as Viking strongholds.

Meanwhile, back in England, the Vikings took over Northumbria, East Anglia and parts

of Mercia. In 866 they captured modern York (Viking name: Jorvik) and made it their

capital. They continued to press south and west. The kings of Mercia and Wessex

resisted as best they could, but with little success until the time of Alfred of Wessex,

the only king of England to be called ‘the Great'.

21. The Scandinavian invasion (the 9th- 11th centuries) (3)

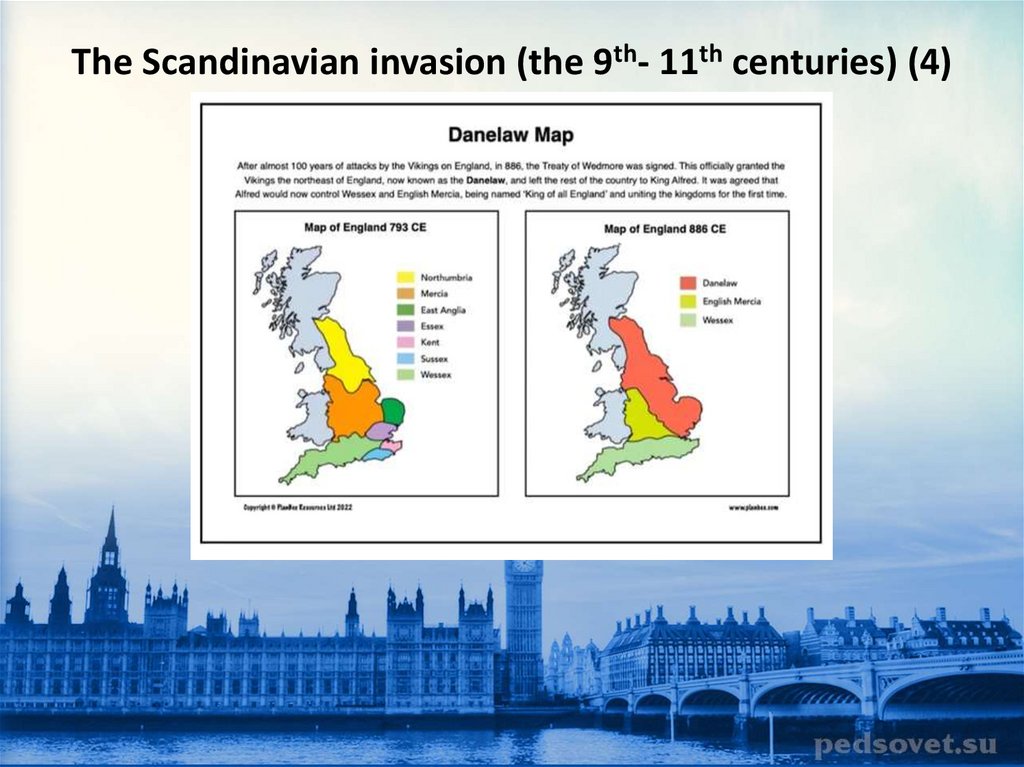

King Alfred and the DanesKing Alfred ruled from 871-899 and after many trials and tribulations he defeated the

Vikings at the Battle of Edington in 878. After the battle the Viking leader Guthrum

converted to Christianity. In 886 Alfred took London from the Vikings and fortified it.

The same year he signed a treaty with Guthrum. The treaty partitioned England

between Vikings and English. The Viking territory became known as the Danelaw. It

comprised the north-west, the north-east and east of England. Here, people would be

subject to Danish laws. Alfred became king of the rest.

Alfred's grandson, Athelstan, became the first true King of England. He led an English

victory over the Vikings at the Battle of Brunaburh in 937, and his kingdom for the first

time included the Danelaw. In 954, Eirik Bloodaxe, the last Viking king of York, was

killed and his kingdom was taken over by English earls.

22. The Scandinavian invasion (the 9th- 11th centuries) (4)

23. The Norman Conquest (1066): the preliminary events

One of the most influential monarchies in the history of England began in 1066 C.E.with the Norman Conquest led by William, the Duke of Normandy. England would

forever be changed politically, economically, and socially as a result.

The conquest was personal to William. He was once promised a higher title, the king

of England. But ultimately, before he died in 1066, England’s King Edward chose a

different successor, Harold Godwinson, an English nobleman. Feeling betrayed,

William gathered an army and made his way to England in hopes of properly taking his

place atop the throne, which was becoming more crowded. Not only were Harold and

William in a power struggle, but there were other challengers to the throne as well,

including Harald III of Norway and Harold Godwinson’s brother, Tostig.

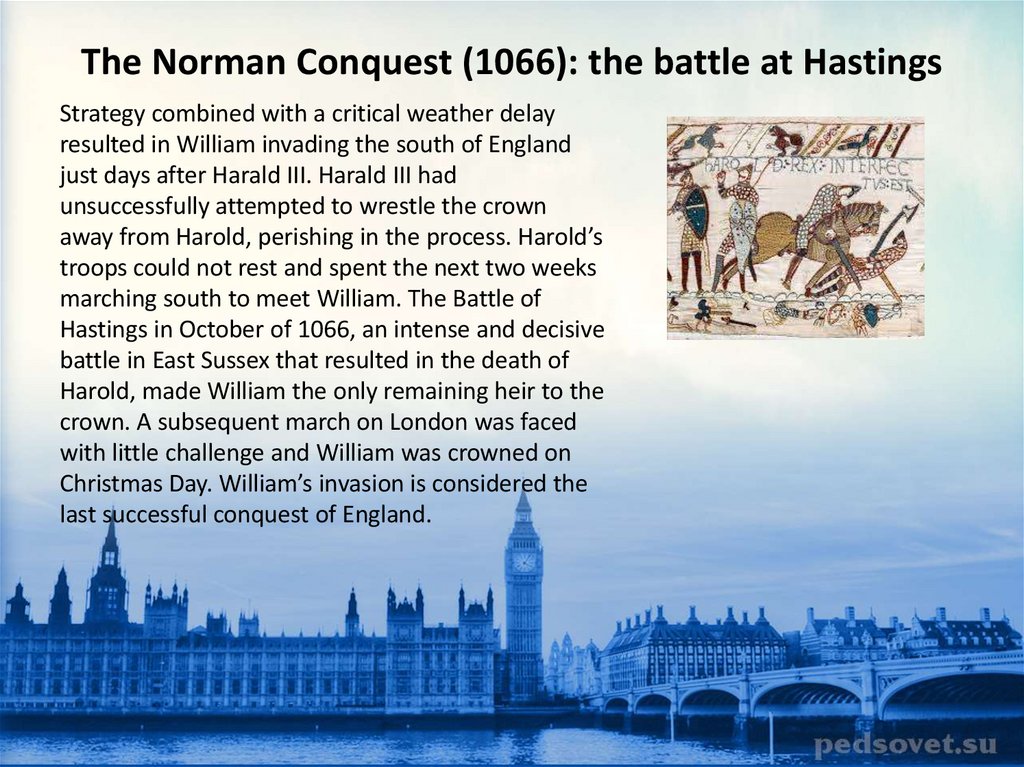

24. The Norman Conquest (1066): the battle at Hastings

Strategy combined with a critical weather delayresulted in William invading the south of England

just days after Harald III. Harald III had

unsuccessfully attempted to wrestle the crown

away from Harold, perishing in the process. Harold’s

troops could not rest and spent the next two weeks

marching south to meet William. The Battle of

Hastings in October of 1066, an intense and decisive

battle in East Sussex that resulted in the death of

Harold, made William the only remaining heir to the

crown. A subsequent march on London was faced

with little challenge and William was crowned on

Christmas Day. William’s invasion is considered the

last successful conquest of England.

25. The Norman Conquest (1066): results (1)

Early on, King William endured a number ofinvasions, attacks, rebellions, and threats.

He survived through a series of military

victories and controversial tactics such as

his devastating “harrying the north” policy.

This policy involved damaging the land in

the north to minimize the chances that

rebel groups could strengthen and

challenge his army. William also introduced

new military strategies, which included

building many castles across the country as

defensive measures.

26. The Norman Conquest (1066): results (2)

English culture changed dramatically as well. William replaced the Englishlandowning elite with Norman landowners, resulting in the first steps toward

feudalism. William also directly redistributed land to these people, often in return

for military service. William ordered that this new system of land ownership be

recorded in a comprehensive manuscript, known as the Domesday Book. He also

replaced the church elite, which was mainly made up of Anglo-Saxons, with his

Norman supporters. Furthermore, the introduction of the French language into elite

English circles influenced English vocabulary and composition.

The results of the Norman Conquest linked England to France in the years that

followed. In addition to the introduction of French words to the English language,

the French influence was also felt in politics, as William and his noblemen retained

an interest in the affairs of France and the European continent.

История

История