Похожие презентации:

Behavioral finance

1. Behavioral Finance

Utevskaya Marina ValerievnaPhD

Saint-Petersburg State University of Economics

Associate Professor, Corporate Finance and Business Evaluation Department

Director of International Master Program “Corporate Finance, Control and Risks”

2. PART III

23. Role of Investor Behavior

• Bounded Rationality: “satisficing” behavior. Informationprocessing limitations. Example: memory limitations.

• Investor Sentiment: beliefs based on heuristics rather than

Bayesian rationality.

• Investors may react to “irrelevant information” and hence

may trade on “noise” rather than information.

4. “Irrational” Behavior of Professional Money Managers

• May choose a portfolio very close to the benchmarkagainst which they are evaluated (for example: S&P500

index).

• Herding: may select stocks that other managers select to

avoid “falling behind” and “looking bad”.

• Window-dressing: add to the portfolio stocks that have

done well in the recent past and sell stocks that have

recently done poorly.

5. An Example

• Initial endowment: $300. Consider a choicebetween:

• a sure gain of $100

• a 50% chance to gain $200, a 50% chance to gain $0.

• Initial endowment: $500. Consider a choice

between:

• a sure loss of $100

• a 50% chance to lose $200, a 50% chance to lose $0.

6. Reversal in Choice

• Case 1: 72% chose option 1, 28% chose option 2.• Case 2: 36% chose option 1, 64% chose option 2.

=> A reversal in Choice

• Problem framed as a gain: decision maker is risk averse.

• Problem framed as a loss: decision maker is risk seeking.

7. Allais Paradox

The Allais paradox is a choice problem designedby Maurice Allais (1953) to show an inconsistency of

actual observed choices with the predictions of expected

utility theory.

The Allais paradox arises when comparing participants'

choices in two different experiments, each of which

consists of a choice between two gambles, A and B.

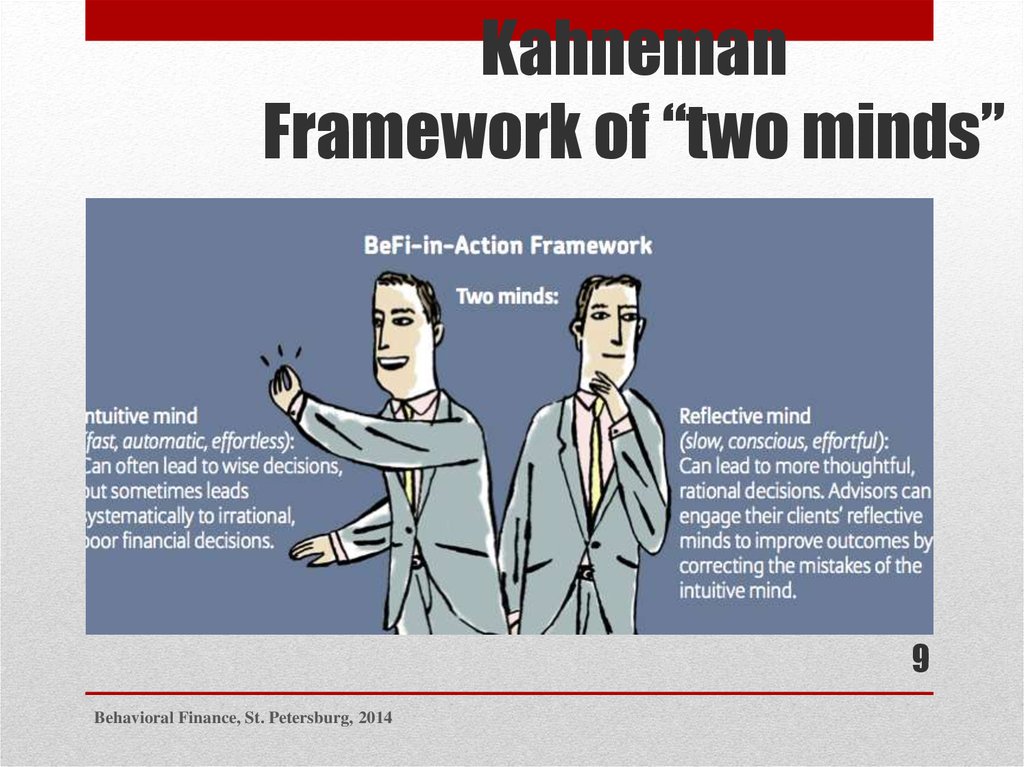

8. Kahneman Framework of “two minds”

• to describe the way people make decisions• an “intuitive” mind: rapid judgments with great ease and

with no conscious input

• “reflective” mind: slow, analytical and requires conscious

effort

8

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

9. Kahneman Framework of “two minds”

9Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

10. Kahneman Framework of “two minds”

Illustration of whatis meant by intuitive

mind, and how it

sometimes leads

one astray

10

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

11. Kahneman Framework of “two minds”

• One of the insights that earned Kahneman the NobelPrize1 is that we humans are sometimes as susceptible to

“cognitive illusions” as we are to optical illusions.

• These illusions, also known as biases, result from the use of

heuristics, or, more simply, mental shortcuts.

• Kahneman’s discovery that under certain circumstances

intuition can systematically lead to incorrect decisions

and judgments changed psychologists’ understanding of

decision making, and, ultimately, economists’, too.

11

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

12. Kahneman Framework of “two minds”

• Behavioral economics showed instead that we are not aslogical as we might think, we do care about others, and

we are not as disciplined as we would like to be.

• It is not that people are irrational in the colloquial sense,

but that by the nature of how our intuitive mind works we

are susceptible to mental shortcuts that lead to erroneous

decisions.

• Our intuitive mind delivers the products of these mental

shortcuts to us, and we accept them. It’s hard to help

ourselves.

12

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

13. Kahneman Framework of “two minds”

• Loss aversion:• described by Prospect Theory (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979)

• losses loom larger than equal-sized gains

• loss aversion affects many of our decisions, including

financial ones

13

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

14. Kahneman Framework of “two minds”

• EXAMPLE• Selling a losing stock is extremely unpalatable because it

brings the reality of loss very much to mind.

• People often sell winning stocks too soon because the act

of selling a winning stock realizes a gain, and that gives

us pleasure.

• The mistake people are making here is one of mental

accounting: instead of looking at their portfolio “as a

whole” they look at each stock separately, and make

decisions based on these separately perceived realities.

14

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

15. Kahneman Framework of “two minds”

• Loss aversion also makes people reluctant to makedecisions for change because they focus on what they

could lose more than on what they might gain. This is

called “inertia,” or the status quo bias (Samuelson and

Zeckhauser, 1988).

• Inertia is at play when people know they should be doing

certain things that are in their best interests (saving for

retirement, dieting to lose weight, or exercising), but find

it hard to do today.

15

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

16. Kahneman Framework of “two minds”

• “We make intuitive judgments all the time, but it’s veryhard for us to tell which ones are right and which ones are

wrong” says Nicholas Barberis, a behavioral finance

researcher at the Yale School of Management

16

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

17. SMarT

• Richard Thaler• Save More TomorrowTM program (SMarT)

• An alarmingly large proportion of employees fail to

participate in their company’s defined contribution

retirement plan, often forgoing matching funds (free

money) from employers

• SMarT effectively removes psychological obstacles to

saving in the short and longer term, and helps people

overcome them with very little effort on their part

17

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

18. SMarT

There are four ingredients to the program:1. Employees are invited to pre-commit to increase their

saving rate in the future. Because of procrastination,

most people find it easier to imagine doing the right

things in the future, similar to our New Year resolutions

to start exercising and dieting next year.

2. For those employees who do enroll, their first increase

in savings coincides with a pay raise so that their takehome pay does not go down. This avoids triggering the

mind’s hypersensitivity to loss, or loss aversion.

18

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

19. SMarT

3. The contribution rate continues to increase automatically with each successive pay raise until a previouslyagreed upon ceiling is reached. Here, inertia is working in

people’s best interest, ensuring that people stay in the plan

and the contribution rate increases.

4. Employees may opt out of the plan at any time they

choose, though experience shows that people rarely do. This

provision makes them more comfortable about joining in

the first place.

19

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

20. SMarT

• In the first case study of SMarT, employees at a midsizemanufacturing company increased their contribution to

their retirement fund from 3.5 percent to 13.6 percent of

salary over a three-and-a-half-year period (Thaler and

Benartzi, 2004). This is a remarkable improvement in

saving behavior. As a result, the program is now offered

by more than half of the large employers in the United

States, and a variant of the program was incorporated in

the Pension Protection Act of 2006 (Hewitt, 2010).

20

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

21. SMarT

• “The lesson of the experience with the SMarT program,therefore, is general and powerful: the strategic

application of a few key psychological principles can

dramatically improve people’s financial decisions.”

• Financial advisors can take advantage of such insights in

their own practices to help their clients make better

decisions which, ultimately, should lead to better

financial outcomes.

21

Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

Финансы

Финансы