Похожие презентации:

Interviewing in qualitative research

1.

Interviewing in qualitative researchLecture 5

2. Qualitative or quantitative methods?

◦ Quantitative methods lose some accuracy in measurement.Measure not all the features of an object, inevitably coarsen a

measurement & measured objects.

◦ Qualitative methods are aimed at obtaining a maximum

information about a small number of objects

◦ Maximum of accuracy

◦ Maximum of characteristics in question.

◦ Qualitative methods have focus on

◦ the most detailed description of behavior & attitudes of social groups

to discover unobserved arguments& meanings (method of focus

groups, ethnomethodology)

◦ description of unique small groups (politicians, businessmen, artists,

doctors, etc.).

3. Features of qualitative research

◦ Inductive view of relationship between theory and research◦ theories and concepts emerge from the data

◦ Interpretivist epistemology

◦ Constructionist ontology

◦ Emphasis on words/text rather than numbers

◦ Diversity of approaches

4.

Grounded theory• Not actually a theory in itself, it is rather an approach to

generating theory from data

• Data collection and analysis are done hand-in-hand, with

constant checking back and forth

• Useful in producing concepts

5. Research methods used in qualitative research

◦ Ethnography / participation observation◦ prolonged immersion in the field

◦ Qualitative interviewing

◦ in-depth, semi- or un-structured

◦ Focus groups

◦ Discourse / conversation analysis (analysis of respondents’

utterance recorded for multiple playback. Interpretation of nonverbal

details (silence, repetitions, gestures, facial expressions, etc.))

◦ Documentary analysis

6. When qualitative methods?

◦ If we study uniqueness, a particular social object, the study of theoverall picture of the event or case in the unity of its components,

the interaction of objective and subjective meanings.

◦ Qualitative research also allows us to study new phenomena or

processes that are not widespread, especially in the context of

dramatic social changes in the conduct, organization and

analysis of data and, most importantly, - a different

understanding and perception of social reality

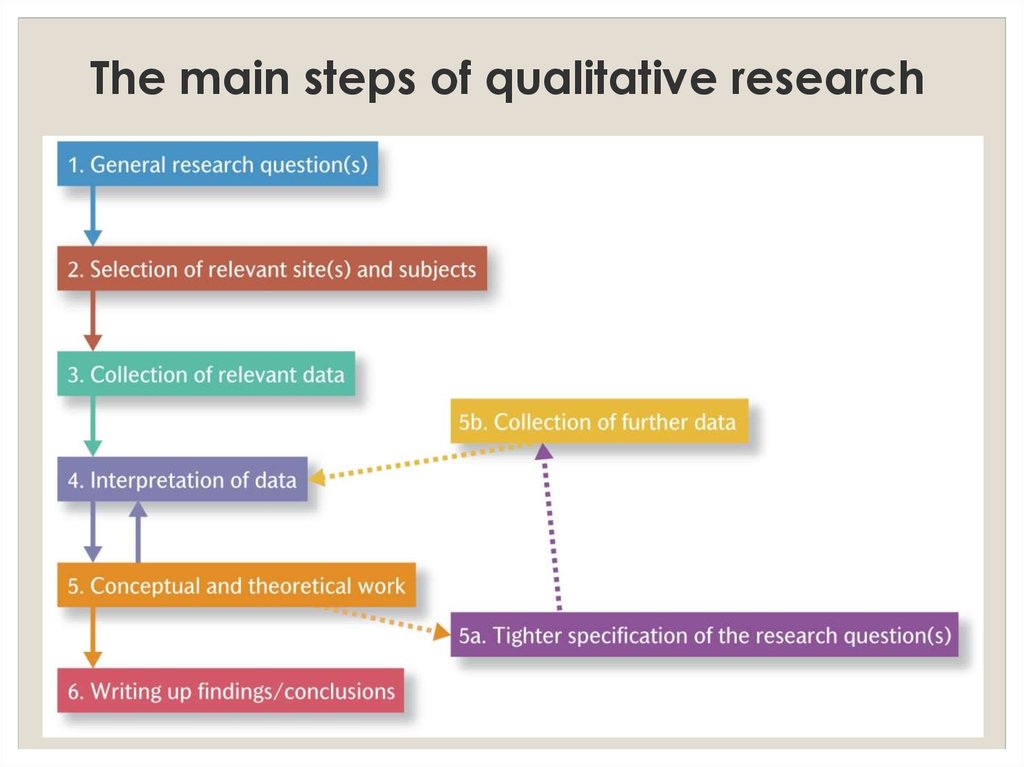

7. The main steps of qualitative research

8. Concepts in qualitative research

Blumer (1954) argued against the use of definitive conceptsin qualitative research:

◦ because the indicators ‘fix’ the concept

◦ because what phenomena have in common

becomes more important than their variety

…and in favour of sensitizing concepts:

◦ giving a general sense of reference and guidance

◦ allowing discovery of varied forms of phenomena

◦ capable of being gradually narrowed down

9. Approaches to reliability and validity

1. Adapting concepts from quantitative researchlittle change of meaning

quality, rigour and wider potential

external reliability (replication)

internal reliability (inter-observer consistency)

internal validity (good fit between data and theory)

external validity (generalization)

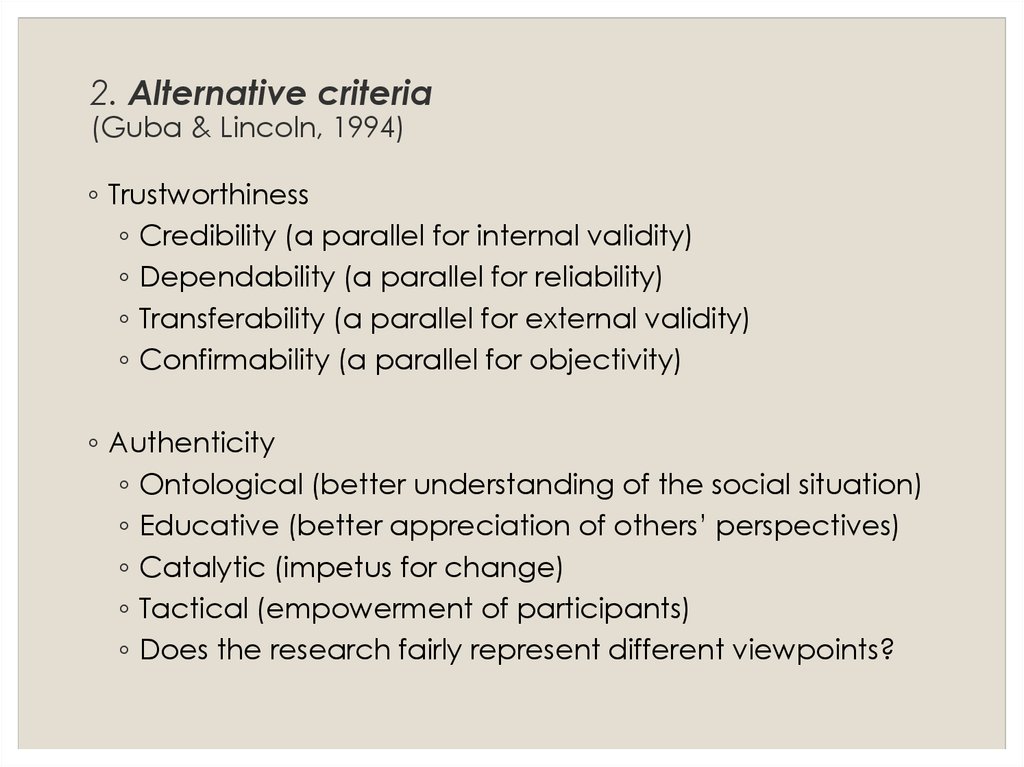

10. 2. Alternative criteria (Guba & Lincoln, 1994)

2. Alternative criteria(Guba & Lincoln, 1994)

◦ Trustworthiness

◦ Credibility (a parallel for internal validity)

◦ Dependability (a parallel for reliability)

◦ Transferability (a parallel for external validity)

◦ Confirmability (a parallel for objectivity)

◦ Authenticity

◦ Ontological (better understanding of the social situation)

◦ Educative (better appreciation of others’ perspectives)

◦ Catalytic (impetus for change)

◦ Tactical (empowerment of participants)

◦ Does the research fairly represent different viewpoints?

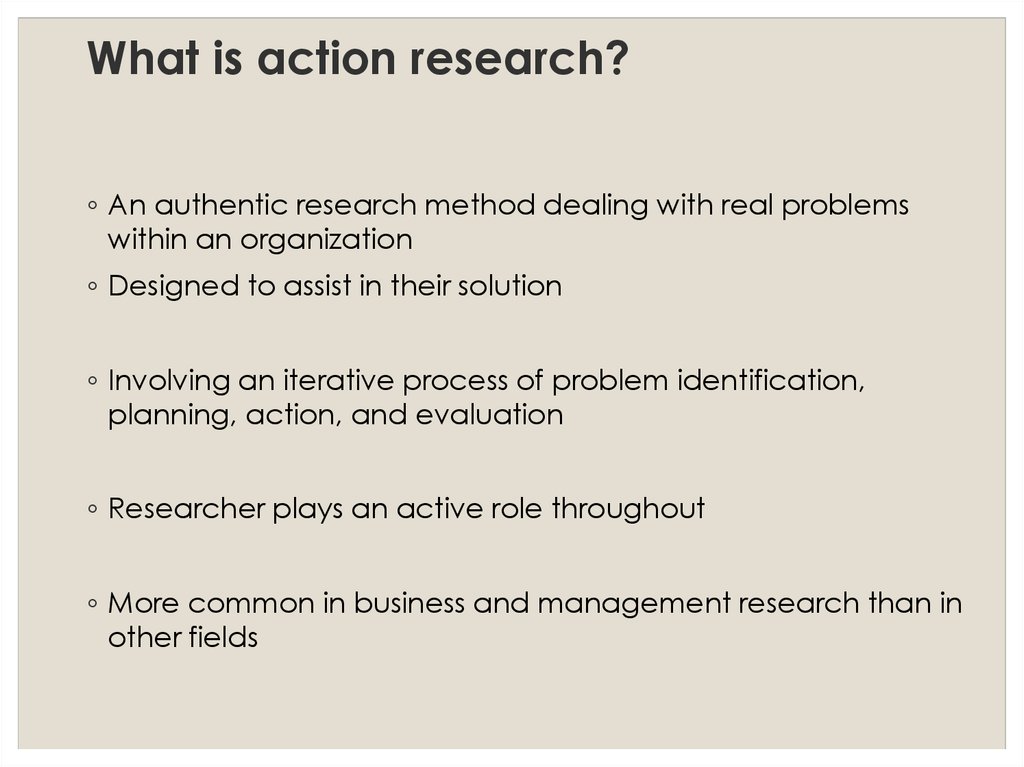

11. What is action research?

◦ An authentic research method dealing with real problemswithin an organization

◦ Designed to assist in their solution

◦ Involving an iterative process of problem identification,

planning, action, and evaluation

◦ Researcher plays an active role throughout

◦ More common in business and management research than in

other fields

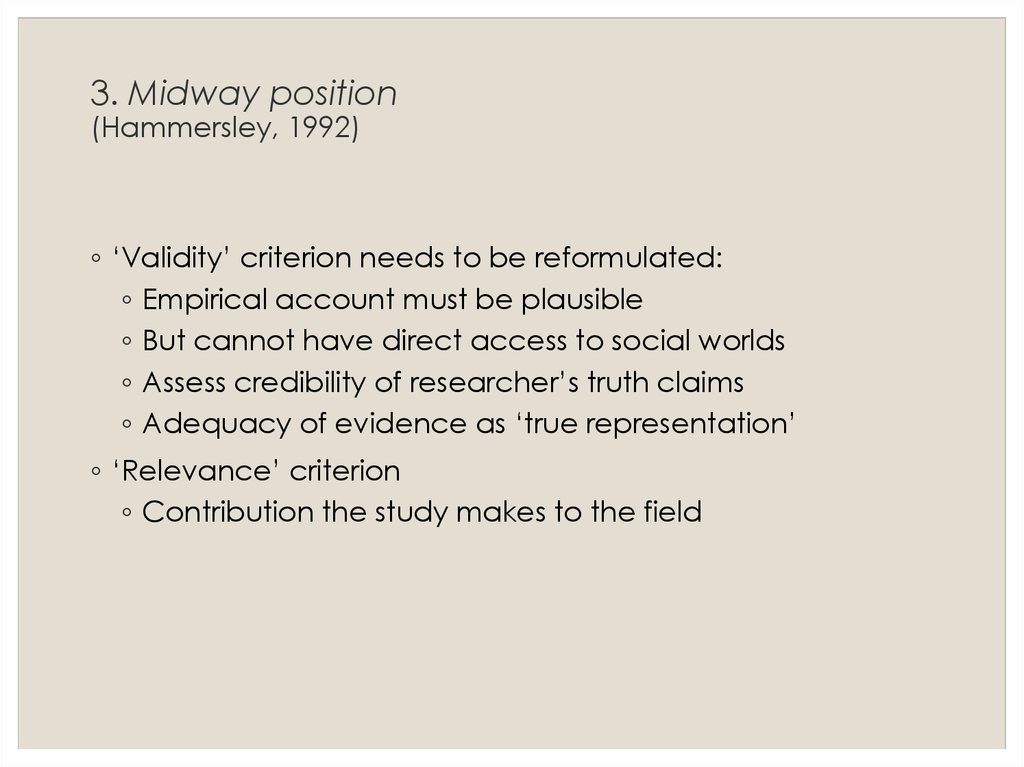

12. 3. Midway position (Hammersley, 1992)

◦ ‘Validity’ criterion needs to be reformulated:◦ Empirical account must be plausible

◦ But cannot have direct access to social worlds

◦ Assess credibility of researcher’s truth claims

◦ Adequacy of evidence as ‘true representation’

◦ ‘Relevance’ criterion

◦ Contribution the study makes to the field

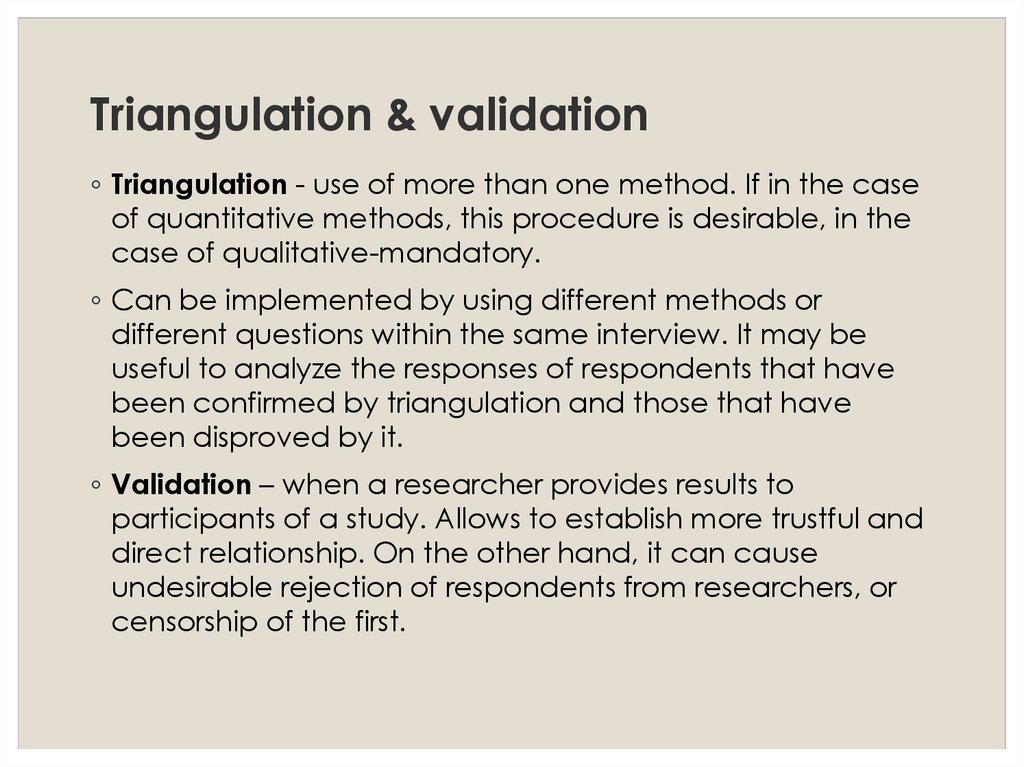

13. Triangulation & validation

Triangulation & validation◦ Triangulation - use of more than one method. If in the case

of quantitative methods, this procedure is desirable, in the

case of qualitative-mandatory.

◦ Can be implemented by using different methods or

different questions within the same interview. It may be

useful to analyze the responses of respondents that have

been confirmed by triangulation and those that have

been disproved by it.

◦ Validation – when a researcher provides results to

participants of a study. Allows to establish more trustful and

direct relationship. On the other hand, it can cause

undesirable rejection of respondents from researchers, or

censorship of the first.

14. The main preoccupations of qualitative researchers 1

◦ Seeing through the eyes of those studied◦ Taking the role of the other

◦ Understanding the meanings people attribute to their

world

◦ Unexpected findings

◦ Description and emphasis on context

◦ Detailed account of the social setting

◦ ‘Thick descriptions’ of what is going on

15. The main preoccupations of qualitative researchers 2

◦ Emphasis on social process◦ How patterns of events unfold over time

◦ Social worlds characterized by change and flux

◦ Flexibility and limited structure

◦ No ‘prior contamination’ by rigid schedules

◦ Sensitizing concepts

◦ Concepts and theory grounded in the data

16. Criticisms of qualitative research

◦ Too subjective◦ Researcher decides what to focus on

◦ Difficult to replicate

◦ Unstructured format

◦ Problems of generalization

◦ Samples not ‘representative’ of all cases

◦ Lack of transparency

◦ Often unclear what researcher actually did

17. Is it always like this?

◦ Some qualitative research departs from these conventions:◦ Focused on a specific research problem (rather than

sensitizing concepts / grounded theory)

◦ More structured data collection (codified conversation

analysis)

◦ More structured data analysis (CAQDAS)

◦ Greater transparency

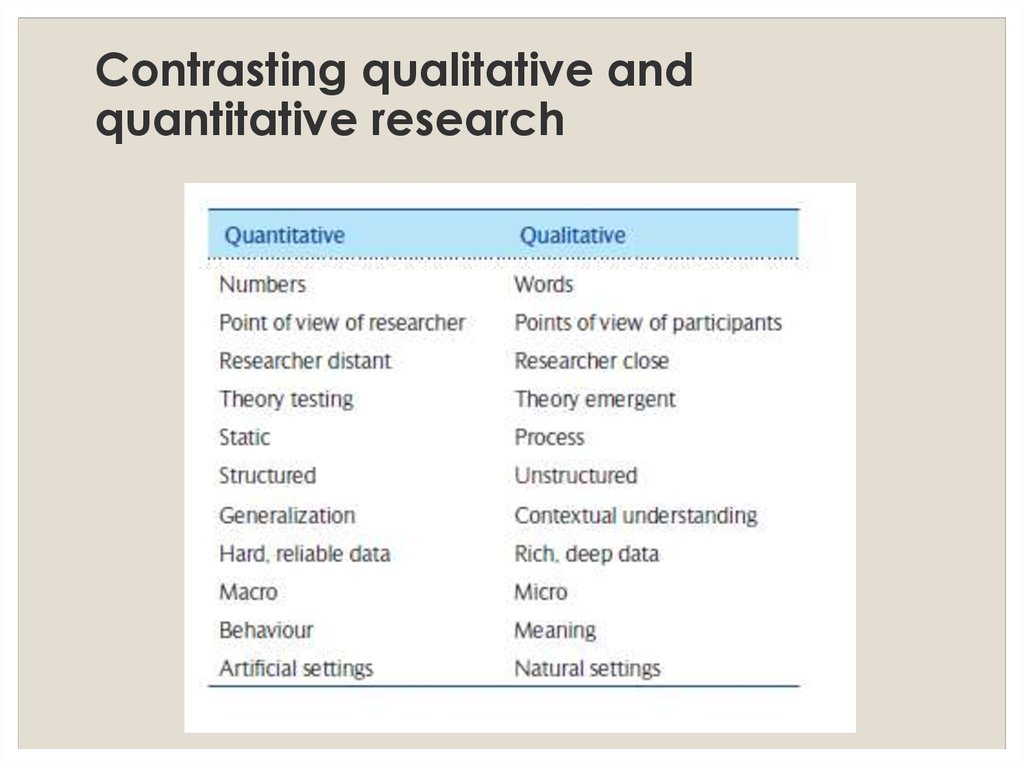

18. Contrasting qualitative and quantitative research

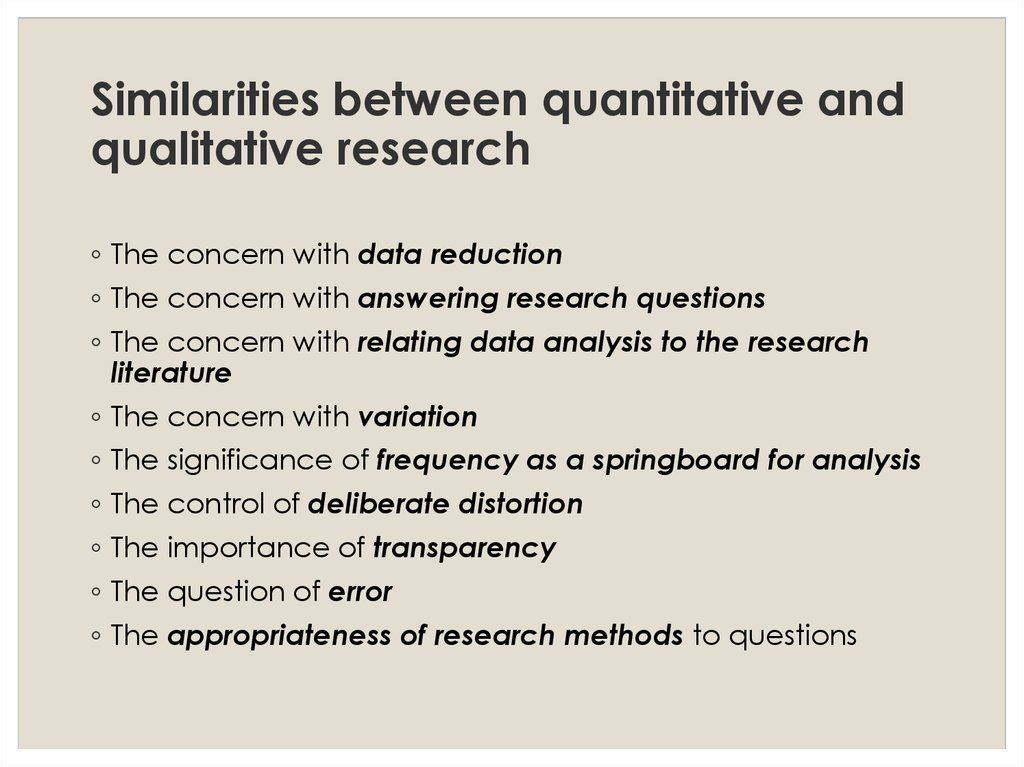

19. Similarities between quantitative and qualitative research

◦ The concern with data reduction◦ The concern with answering research questions

◦ The concern with relating data analysis to the research

literature

◦ The concern with variation

◦ The significance of frequency as a springboard for analysis

◦ The control of deliberate distortion

◦ The importance of transparency

◦ The question of error

◦ The appropriateness of research methods to questions

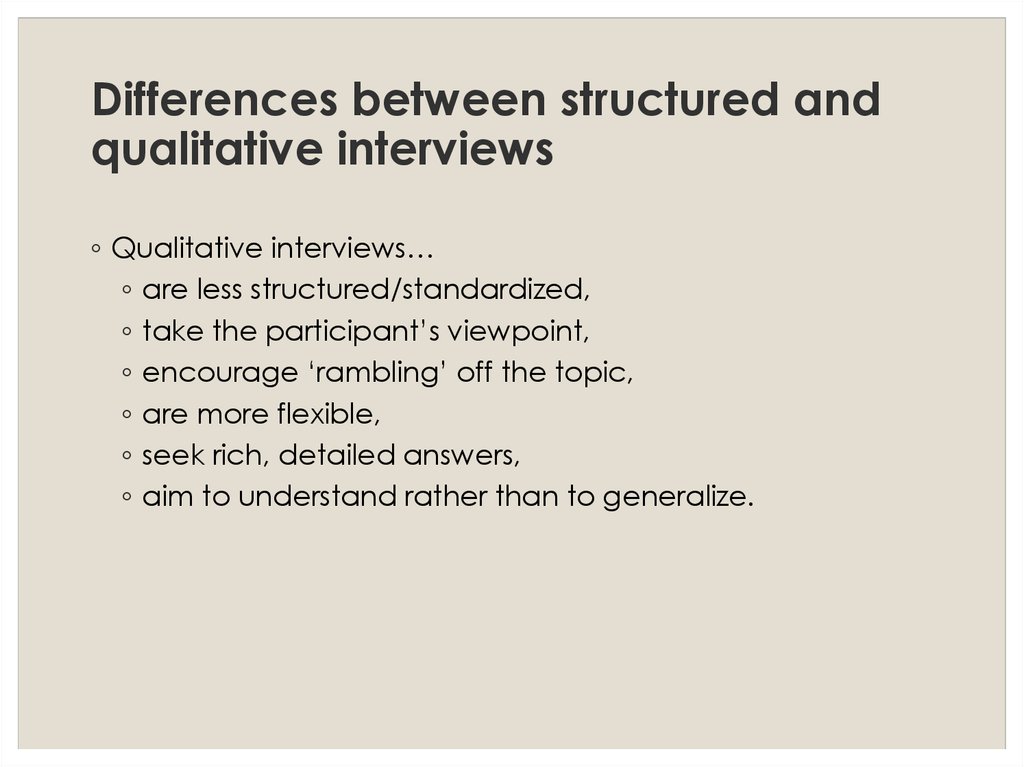

20. Differences between structured and qualitative interviews

◦ Qualitative interviews…◦ are less structured/standardized,

◦ take the participant’s viewpoint,

◦ encourage ‘rambling’ off the topic,

◦ are more flexible,

◦ seek rich, detailed answers,

◦ aim to understand rather than to generalize.

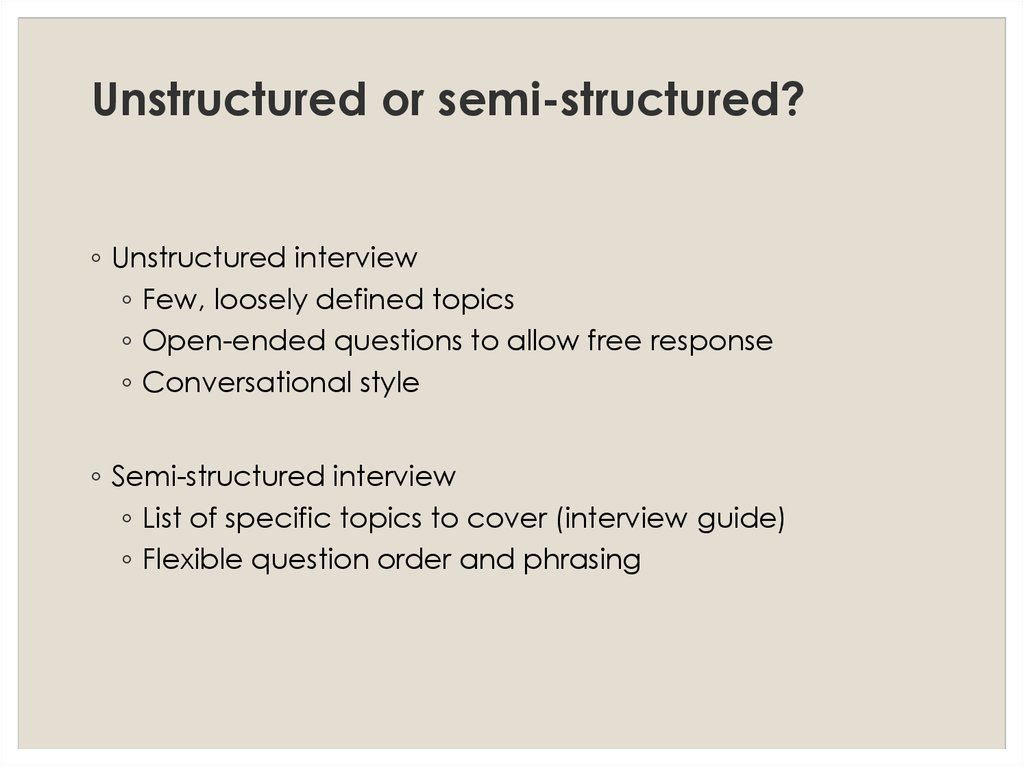

21. Unstructured or semi-structured?

◦ Unstructured interview◦ Few, loosely defined topics

◦ Open-ended questions to allow free response

◦ Conversational style

◦ Semi-structured interview

◦ List of specific topics to cover (interview guide)

◦ Flexible question order and phrasing

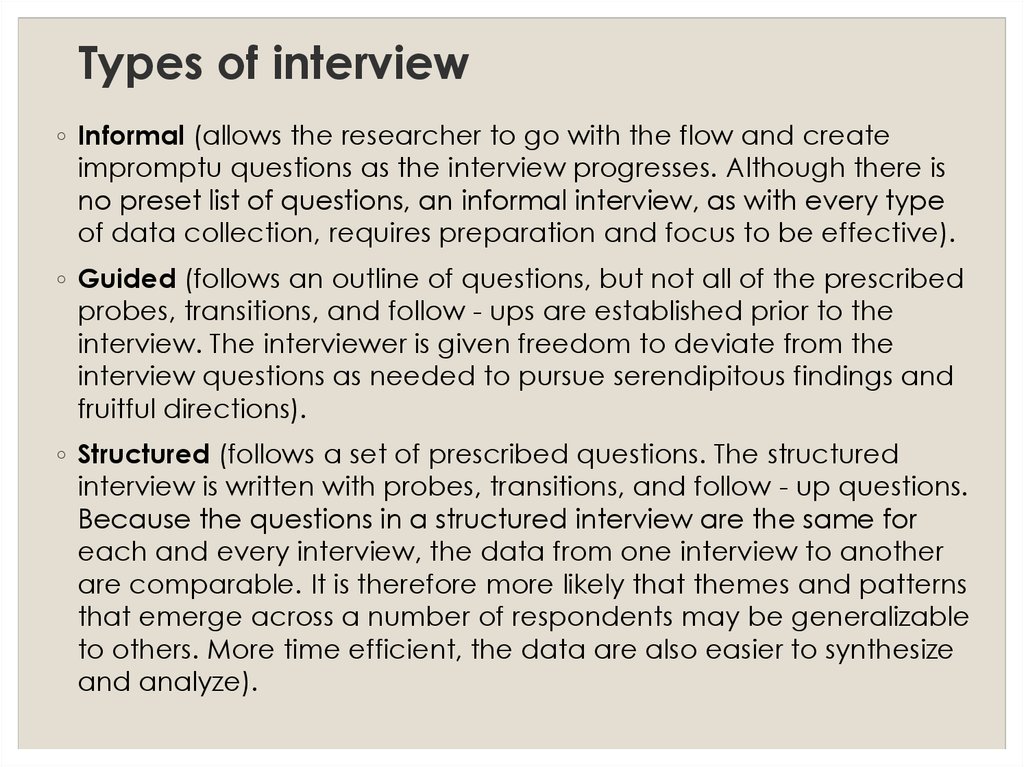

22. Types of interview

◦ Informal (allows the researcher to go with the flow and createimpromptu questions as the interview progresses. Although there is

no preset list of questions, an informal interview, as with every type

of data collection, requires preparation and focus to be effective).

◦ Guided (follows an outline of questions, but not all of the prescribed

probes, transitions, and follow - ups are established prior to the

interview. The interviewer is given freedom to deviate from the

interview questions as needed to pursue serendipitous findings and

fruitful directions).

◦ Structured (follows a set of prescribed questions. The structured

interview is written with probes, transitions, and follow - up questions.

Because the questions in a structured interview are the same for

each and every interview, the data from one interview to another

are comparable. It is therefore more likely that themes and patterns

that emerge across a number of respondents may be generalizable

to others. More time efficient, the data are also easier to synthesize

and analyze).

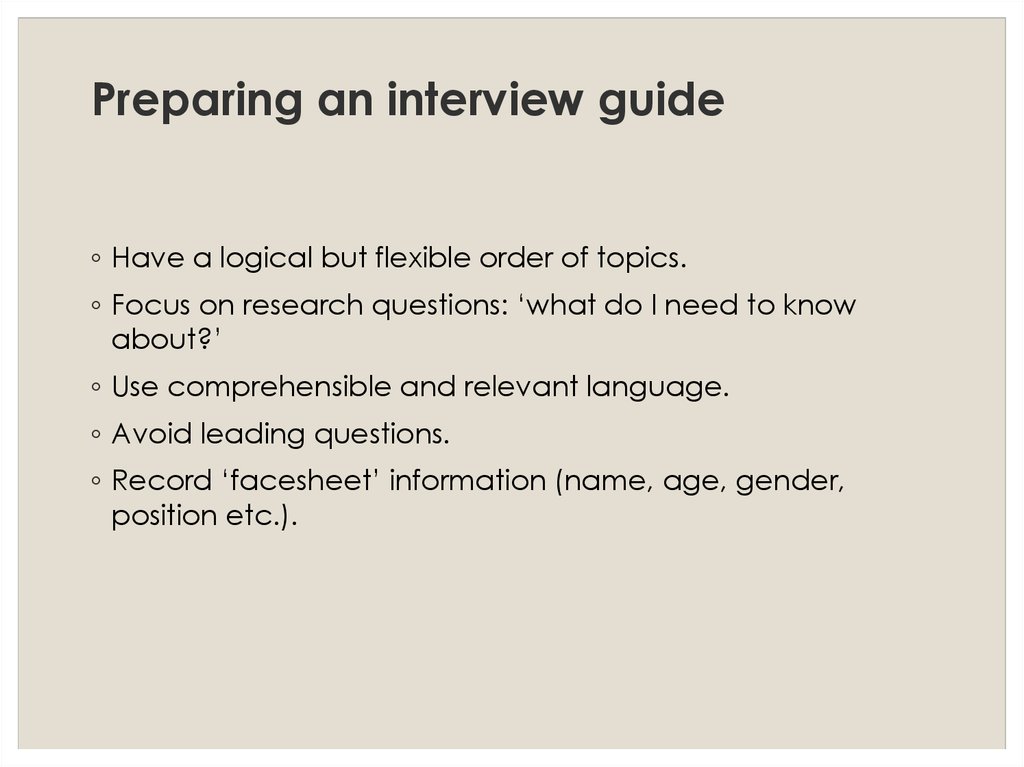

23. Preparing an interview guide

◦ Have a logical but flexible order of topics.◦ Focus on research questions: ‘what do I need to know

about?’

◦ Use comprehensible and relevant language.

◦ Avoid leading questions.

◦ Record ‘facesheet’ information (name, age, gender,

position etc.).

24.

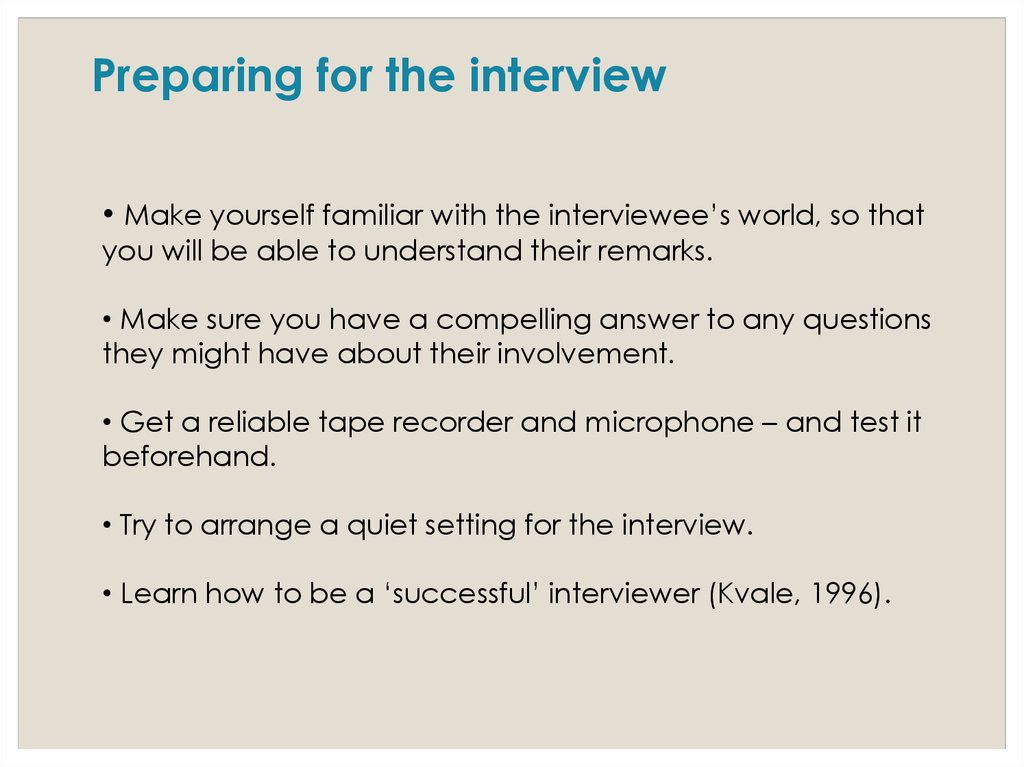

Preparing for the interview• Make yourself familiar with the interviewee’s world, so that

you will be able to understand their remarks.

• Make sure you have a compelling answer to any questions

they might have about their involvement.

• Get a reliable tape recorder and microphone – and test it

beforehand.

• Try to arrange a quiet setting for the interview.

• Learn how to be a ‘successful’ interviewer (Kvale, 1996).

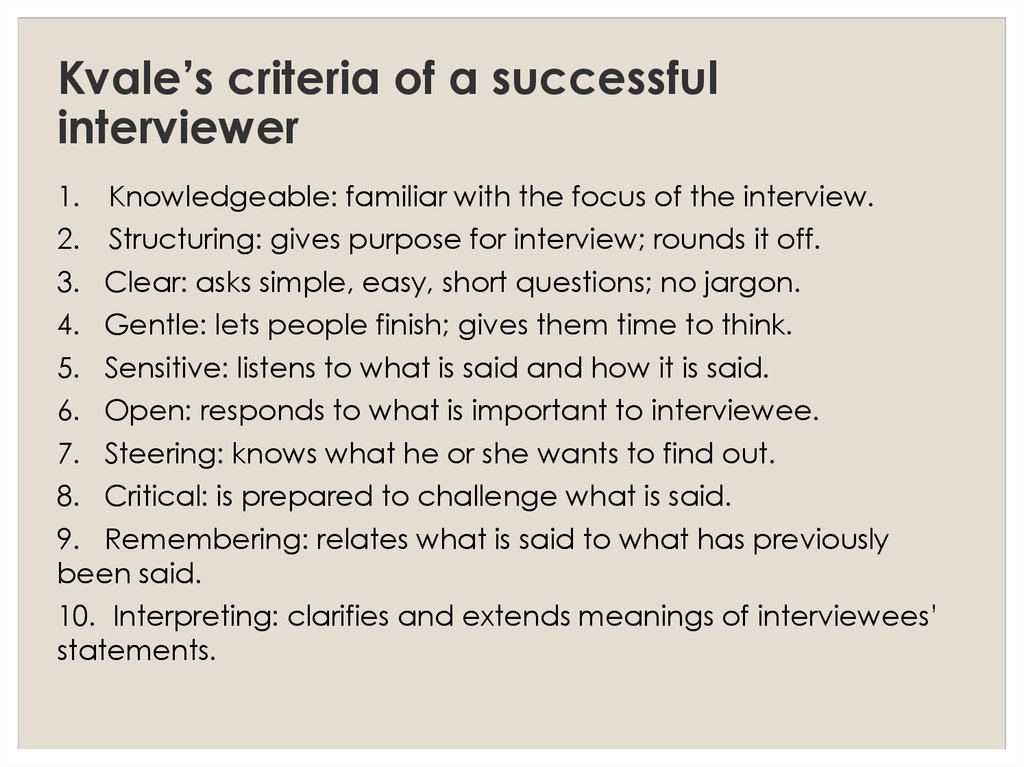

25. Kvale’s criteria of a successful interviewer

1. Knowledgeable: familiar with the focus of the interview.2. Structuring: gives purpose for interview; rounds it off.

3. Clear: asks simple, easy, short questions; no jargon.

4. Gentle: lets people finish; gives them time to think.

5. Sensitive: listens to what is said and how it is said.

6. Open: responds to what is important to interviewee.

7. Steering: knows what he or she wants to find out.

8. Critical: is prepared to challenge what is said.

9. Remembering: relates what is said to what has previously

been said.

10. Interpreting: clarifies and extends meanings of interviewees’

statements.

26. Make notes after the interview

◦ How did the interview go (was interviewee talkative,cooperative, nervous, well-dressed/scruffy, etc.)?

◦ Where did the interview take place?

◦ Did the interview open up new avenues of interest?

◦ What was the setting like (busy/quiet, many/few other

people in the vicinity, new/old buildings)?

27.

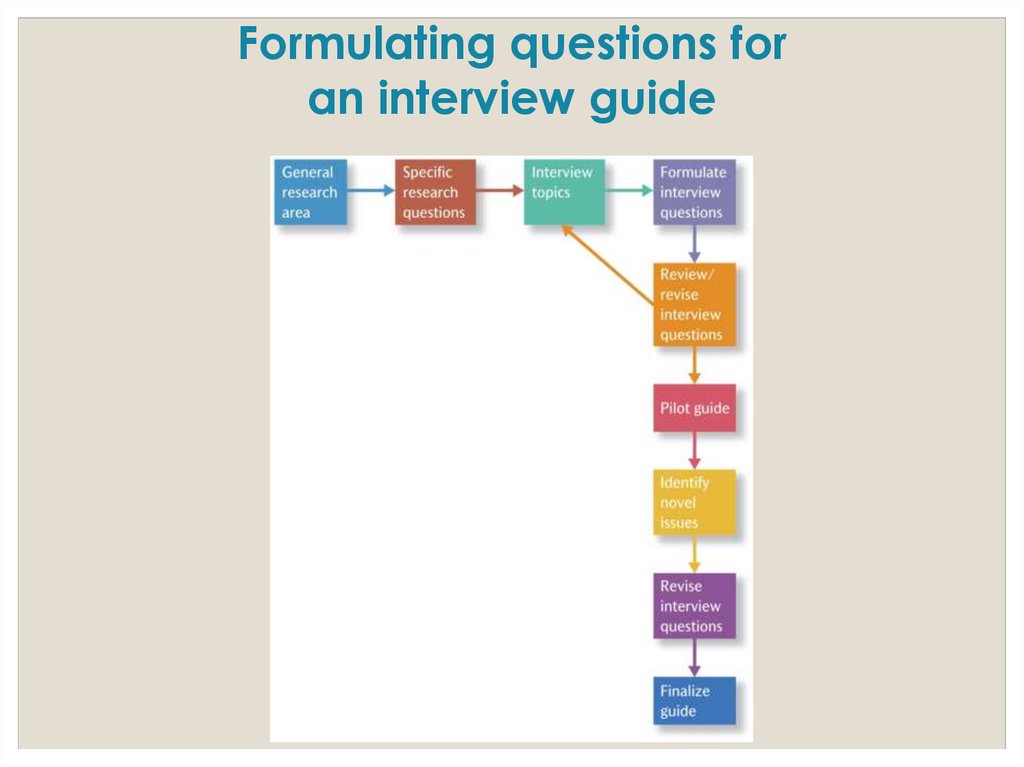

Formulating questions foran interview guide

28. Interview Format and Types of Questions

◦ Background information includes such personal information asdemographics (e.g., age, marital status, education level,

socioeconomic status), pertinent personal history, factual questions.

Demographic and factual questions (easy to answer, and beginning

with this type of question can help to put the respondent at ease).

◦ The second part of the interview should address the respondent ’ s

experience with the group, culture, or program under study. In this part

of the interview, description questions are used: “What is your job

description? ” “You’ve just walked in the door of your office. Describe

what you do first. What do you do next, and next?” “You said you

prepare for the morning conference. How do you prepare for the

conference meeting? ”

◦ Sensory questions are a specific type of description question. Sensory

questions ask respondents what they see, hear, smell, touch, and taste

as part of the experience under study. The researcher must play the

naïve observer in this part of the interview.

29. Interview Format and Types of Questions 2

◦ The third part of the interview should explore the respondent ’ smeanings, interpretations, and associations in regard to the

experiences described. To get at these underlying constructions

of meaning, it is sometimes helpful to ask comparison questions.

◦ To ascertain meanings, interpretations, and associations, it is

also helpful to ask feeling questions ( “ How do you feel about . .

.”), opinion questions (“What do you think or believe about . . .

”), and value questions (“To what extent is this good/moral or

bad/immoral?”).

◦ Seidman (1991) recommends using a three - interview format,

with each interview dedicated to one of the three foci:

background, experience, and meaning. This allows the

researcher to use the background information to develop

questions about the experience and to use the understanding

of the experience to develop questions about the meanings

and associations of key concepts.

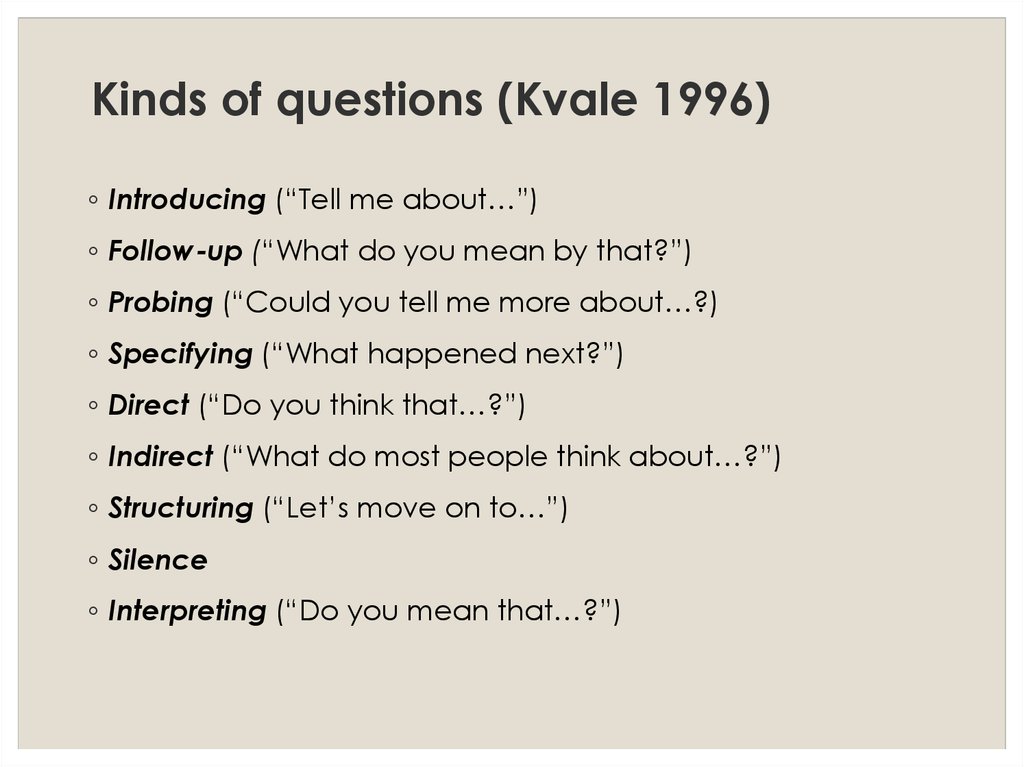

30. Kinds of questions (Kvale 1996)

◦ Introducing (“Tell me about…”)◦ Follow-up (“What do you mean by that?”)

◦ Probing (“Could you tell me more about…?)

◦ Specifying (“What happened next?”)

◦ Direct (“Do you think that…?”)

◦ Indirect (“What do most people think about…?”)

◦ Structuring (“Let’s move on to…”)

◦ Silence

◦ Interpreting (“Do you mean that…?”)

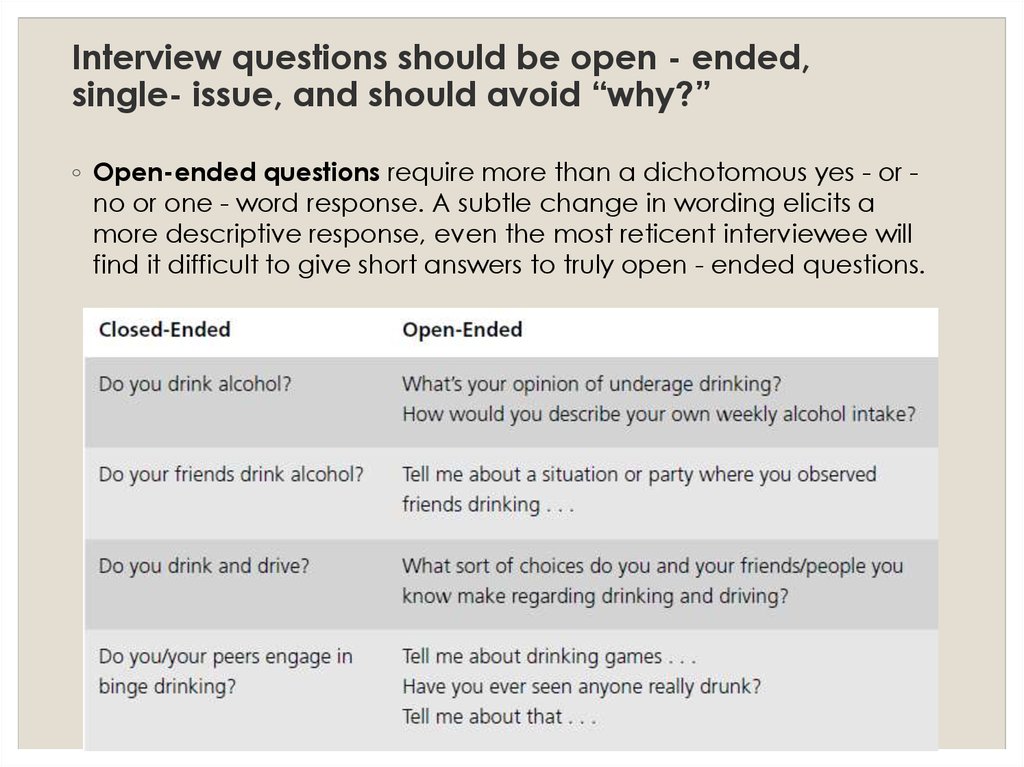

31. Interview questions should be open - ended, single- issue, and should avoid “why?”

◦ Open-ended questions require more than a dichotomous yes - or no or one - word response. A subtle change in wording elicits amore descriptive response, even the most reticent interviewee will

find it difficult to give short answers to truly open - ended questions.

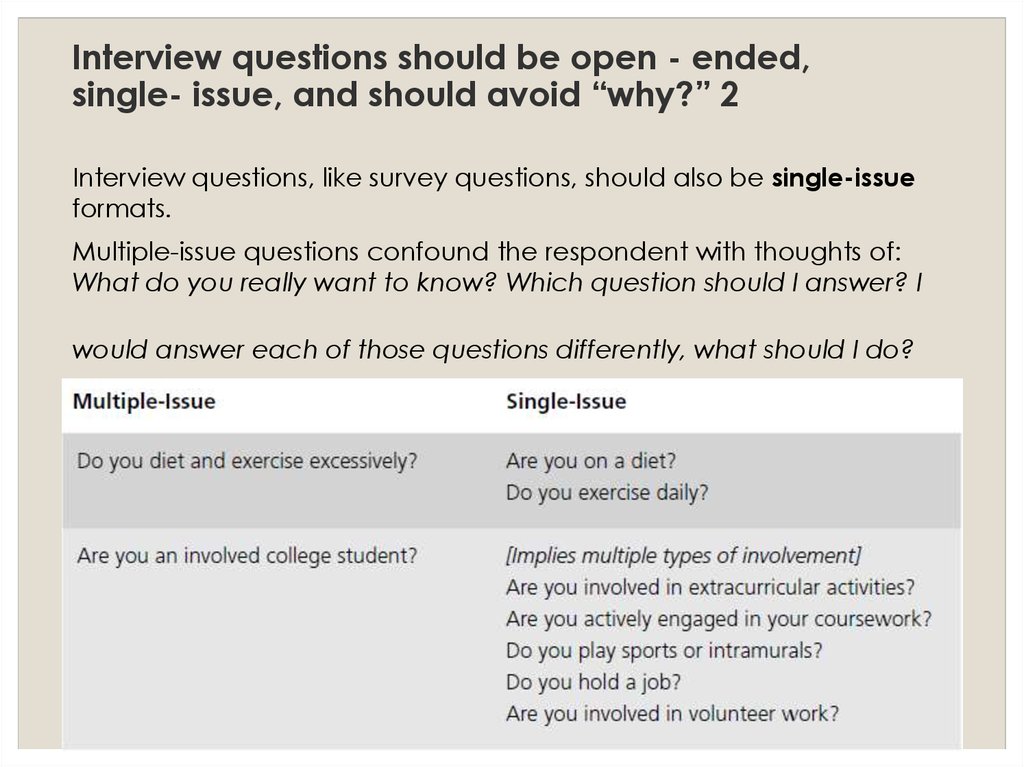

32. Interview questions should be open - ended, single- issue, and should avoid “why?” 2

Interview questions, like survey questions, should also be single-issueformats.

Multiple-issue questions confound the respondent with thoughts of:

What do you really want to know? Which question should I answer? I

would answer each of those questions differently, what should I do?

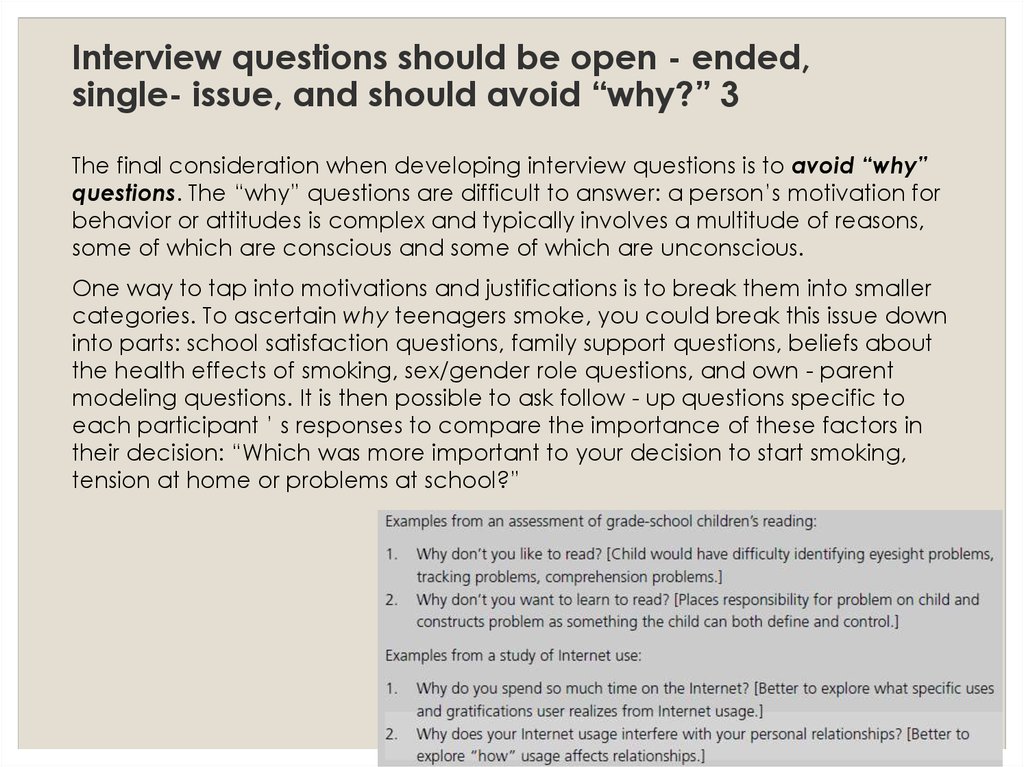

33. Interview questions should be open - ended, single- issue, and should avoid “why?” 3

The final consideration when developing interview questions is to avoid “why”questions. The “why” questions are difficult to answer: a person’s motivation for

behavior or attitudes is complex and typically involves a multitude of reasons,

some of which are conscious and some of which are unconscious.

One way to tap into motivations and justifications is to break them into smaller

categories. To ascertain why teenagers smoke, you could break this issue down

into parts: school satisfaction questions, family support questions, beliefs about

the health effects of smoking, sex/gender role questions, and own - parent

modeling questions. It is then possible to ask follow - up questions specific to

each participant ’ s responses to compare the importance of these factors in

their decision: “Which was more important to your decision to start smoking,

tension at home or problems at school?”

34. Prompts

◦ Interviewers need not rely on the interview guide aloneand other material can be used to stimulate discussion:

◦ Vignettes

◦ Documents

◦ Photographs

◦ Material objects

◦ Physical world (the ‘walking interview’)

◦ These prompts can be researcher or participant driven.

35. Sequencing

Each interview requires a set up, the building of rapport, and a closing. Each ofthese components serves important functions for the interviewer - respondent

relationship.

◦ The set up informs the participant of the roles and expectations for the

interviewer and interviewee. The purpose of the interview, the estimated length

of the interview, and the type of questions to be explored should be

previewed.

◦ Affirmation and feedback are particularly important to build rapport . As the

respondent reveals more personal information, the nonverbals of the

interviewer must communicate interest, respect, appreciation, empathy, and

acceptance. Head - nodding, a forward lean, and nonfluencies such as “ uh huh ” are useful feedback techniques when used subtly and in moderation.

Verbal feedback may, in certain situations, be appropriate, but should be used

with caution.

◦ The closing of the interview should bring the respondent back to the present

environment. This means that you cannot leave a respondent in the depths of

interpretation and disclosure. The skillful interviewer gradually decreases the

intensity of the questions in the closing process. An open - ended closing

question such as “ Is there anything else that you ’ d like to add? ” or “ Is there

anything that I haven ’ t covered in the interview that you ’ d like to talk about?

” gives the respondent an opportunity to address, redirect, and/or correct the

research agenda.

36. Recording and transcription

◦ Audio-recording and transcribing:◦ Researcher is not distracted by note-taking.

◦ Can focus on listening and interpreting.

◦ Corrects limitations of memory and intuitive glosses

(Heritage, 1984).

◦ Detailed and accurate record of interviewee’s account.

◦ Opens data to public scrutiny.

◦ Good quality digital recorders are now widely available.

◦ Transcriber or transcription software?

◦ Selective transcription saves time.

37. Telephone interviewing

◦ Many advantages to conducting interviews via telephone.◦ Cost – it is much cheaper and reduces travel time etc.

◦ Useful for physically dispersed samples.

◦ Some evidence suggests little difference in the answers

given via telephone and in-person (e.g. Sturgis and

Hanrahan, 2004).

◦ But there are also some drawbacks.

◦ Some groups may have limited access to a telephone.

◦ Telephone conversations are much more vulnerable to

disruption, and termination.

◦ Very difficult to observe body language and situational

cues. Skype?

◦ Issues of technology.

38. Special types of qualitative interview

◦ Life history interview◦ Subject looks back across their entire life.

◦ Reveals how they interpret, understand and define the

social world (Faraday & Plummer, 1979).

◦ Shows how life events have unfolded.

◦ Naturalistic, researched or reflexive (Plummer, 2001).

◦ Oral history interview

◦ Subject reflects on specific events in the past.

39. Online interviewing

Online personal interviews for qualitative research◦ Textual in nature: email exchanges, direct messaging,

forums.

◦ Asynchronous/synchronous.

◦ Delivery of questions/answers made one-at-a-time, small

batches, all-at-once?

◦ Editing – issues of reliability.

◦ ‘Spamming’ – issues of validity.

◦ Evidence currently suggests a nuanced picture when

comparing with face-to-face interviews (e.g. Curasi, 2001).

40. Using Skype

◦ A form of synchronous interview conducted via webcams availablethrough PCs, tablets, and smartphones. Similar to a telephone but

with live video.

◦ Retains visual element of the face-to-face interview.

◦ Flexible.

◦ Useful for dispersed samples.

◦ Savings in terms time and cost.

◦ Participant convenience.

◦ Fewer concerns around researcher safety.

◦ Little evidence to suggest problems with rapport etc.

◦ There are, however, particular issues of concern.

◦ Accessibility.

◦ Quality of connection.

◦ Transcription (unlike personal online interviews).

◦ Respondents may be affected by visual characteristics of

interviewer.

◦ Evidence to suggest respondents more likely to ‘no show’ than in

face-to-face interviews.

41. Advantages of participant observation over qualitative interviewing

◦◦

◦

◦

◦

◦

◦

◦

Seeing through others’ eyes

Learning the native language

Taken for granted ideas more likely to be revealed

Access to deviant or hidden activities

Sensitivity to context of action

Flexibility in encountering the unexpected

Naturalistic emphasis

Embodied nature of the experience

42. Advantages of qualitative interviewing over participant observation

◦◦

◦

◦

◦

◦

◦

◦

Finding out about issues resistant to observation

Interviewees reflect on past events / life course

More ethically defensible

Fewer reactive effects

Less intrusive

Longitudinal research (follow-up interviews)

Greater breadth of coverage

Specific focus

43. Home reading for the forthcoming seminar

◦ A. Bryman Social Research Methods 4th edition. Chapters17 & 20. (Dropbox)

◦ Vanderstoep S.W., Johnston D.D. Research Methods for

Everyday life. Blending qualitative and Quantitative

approaches. Chapters 9 and 10. (Dropbox)

◦ Lomand T.C. Social Science Research. A Cross Section of

Journal Articles for Discussion and Evaluation. 7th edition.

Chapters (Articles) 7, 8 and 29.

Социология

Социология