Похожие презентации:

School of management. Models of decision making

1.

SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENTGiancarlo Vecchi

POLICY ANALYSIS COURSE 2022

4. MODELS OF DECISION MAKING

2.

1. DECISION MAKING MODELSSolution A

Solution B

Problem

Solution C

Solution D

To decide (from latin de-caedere) means “to cut off”

It is impossible to observe the very moment in which

a decision is made (when the alternatives are cut off)

The decision is a process

Giancarlo Vecchi

3.

2. Main Variables of a D-M ModelA decision-making model is a short

description of the main features of the

decision-making process:

§ the properties of the decision-maker

§ who is he/she?

§ his/her cognitive capabilities

§ how do he/she think?

§ how solutions are searched and

assessed

§ how the final choice is made

Giancarlo Vecchi

4.

3.a) The rational model

Giancarlo Vecchi

5.

3.A decision is a process in which the actor:

§ Knows all his/her objectives

§ Is able to rank the objectives in an order of

preferences (prioritisation)

§ Knows all the alternatives courses of action

§ Is able to measure costs and benefits of

every alternative

§ Chooses the alternative maximising the

benefit/cost ratio (optimizing approach)

Giancarlo Vecchi

6.

3. The rational choice elementsCompleteness – all possible courses of action can

be ranked in an order of preference

To be able to do that, you need a lot of

information about the state of the world and

the outcome of your actions. In the rational

choice model, actors have the sufficient level of

information.

Transitivity – if action A is preferred to B, and

action B is preferred to C, then A is preferred to

C (also, local non-satiation, independence of

irrelevant alternatives – IIA)

An actor will select a course of action that yields

the highest utility (under resource constraints):

maximization

Giancarlo Vecchi

7.

3.The rational model is based on

• the idea of economic rationality as it

developed in economic theory

• The idea of bureaucratic rationality as

formulated by sociological theories of

organization and industrial society

• BUT: IS THE MAIN MODEL OF

SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH: à ITS BASES

ARE ON THE KNOWLEDGE OF

EXPERTS, SO THEY PLAY A

FUNDAMENTAL ROLE

Giancarlo Vecchi

8.

3.Methods for rational decision-making

§ Cost-Benefit Analysis

§ Multicriteria Analysis

§ Environmental Impact Assessment

§ Operational Research

§ etc

Giancarlo Vecchi

9.

3.Rational decision-making.

Reasons for its success

§ Making technique prevail over politics

§ Overcoming the bureaucratic behavior of

public servants

§ Computation capabilities

Giancarlo Vecchi

10.

3.Conditions for operating with the

rational model

§ Well-structured problem (without ambiguity)

§ Non contradictory goals

§ Possibility of setting goals before means

§ Availability of causal theories: if A à then

(always) B, in a invariable/changeless context

condition à the behaviour of B is explained by

the behaviour of A (and only A)

Giancarlo Vecchi

11.

3.§ Single decision-maker (or well coherent

group)

§ Time availability

Giancarlo Vecchi

12.

3.• STRATEGIES IF YOU, AS AN EXPERT

OR A PROMOTER OF A PROJECT,

NEED “MORE KNOWLEDGE”

a) Claim for more time before the final decision,

underlying the future costs of a sub-optimal

solution

b) Claim to study good practices around the world

c) Claim for valid and consistent basic information

d) …

Giancarlo Vecchi

13.

3.Too pretentious?

This type of rationality has been defined as:

§ Olympic (Simon)

§ Synoptic (Lindblom)

§ Comprehensive

As we often cannot defeat uncertainty, we have to

practice other methods that are less pretentious,

such as:

a) the bounded rationality model

b) the incremental model

c) the garbage can model

Giancarlo Vecchi

14.

4.b) The bounded rationality

model (or procedural

rationality)

Giancarlo Vecchi

15.

4.Herbert Simon (economist, political scientist,

sociologist of organizations) observed that very

often in real life decisions are made by people

that are limited by:

§ limited knowledge

§ limited attention span: problems must be dealt

with on a serial, on-at-a-time basis, since decision

makers cannot think about too many issues at the

same time; attention shifts from one value to

another;

§ limited memory, limit on the storage capacity of

the human mind;

à

Giancarlo Vecchi

16.

4.§ habit and routine: human beings and

§

§

§

§

organizational behaviour structured in routines to

manage in a experienced way the same type of

situations

organisational environments which frames the

process of choice

time availability

consequences that cannot be known, so that the

decision-maker relies on a capacity to make

valuations;

etc.

Giancarlo Vecchi

17.

4.Therefore, the ideal of perfect (substantial)

rationality must be dismissed in favour of

limited (procedural) rationality

An individual is rational if the behaviour is

purposive, intentional, i.e. directed at

realising the goals of expressed values

In this situation the criterion of choice is not

optimising but satisficing, i.e. reaching a

decision that is good enough

Giancarlo Vecchi

18.

4.This conclusion can be reached also through the

observation that:

§ most decisions in political settings are taken by

a plurality of actors (coalitions)

§ the solution is often reached through a

sequential assessment (and not a parallel

investigations with the comparison among all

the available alternatives) that stops when the

first “good enough” solution is found

Giancarlo Vecchi

19.

4.Satisfaction criterion and sequential assessment/a

Satisficing is the strategy of considering the

options available to you for choice until you

find one that meets or exceeds a predefined

threshold—your aspiration level—for a

minimally acceptable outcome.

Giancarlo Vecchi

20.

4.Satisfaction criterion and sequential assessment/b

Sequential assessment: if you find the first

option meets your minimum aspirations, and if

you have not time to search for many

alternatives, you can stop your decision

making process, without compare it with other

available alternatives

If the first isn’t good in a sufficient level, you will

analyze the second option, and compare it

with your desired minimum level of aspiration,

repeating the ‘satisfaction procedure’.

This a sequential, linear, procedure

Giancarlo Vecchi

21.

4.STRATEGIES IF YOU ARE THE DESIGNER

• Be sure that your proposal reached the agenda

(it is part of the group of the solutions that will be

discussed)

• Claim to present your proposal as the first, and

• Define before the decisional process, the rules

about ”How to decide” with the aim to analyze

firstly your proposals

Giancarlo Vecchi

22.

4.Interlude: the Condorcet/Arrow

paradox

A given order of preferences is transitive

when

• if choice A is preferred to choice B

and

• choice B is preferred to choice C

then

• choice A is preferred to choice C

Giancarlo Vecchi

23.

4.Example: choosing energy policy

Giancarlo Vecchi

24.

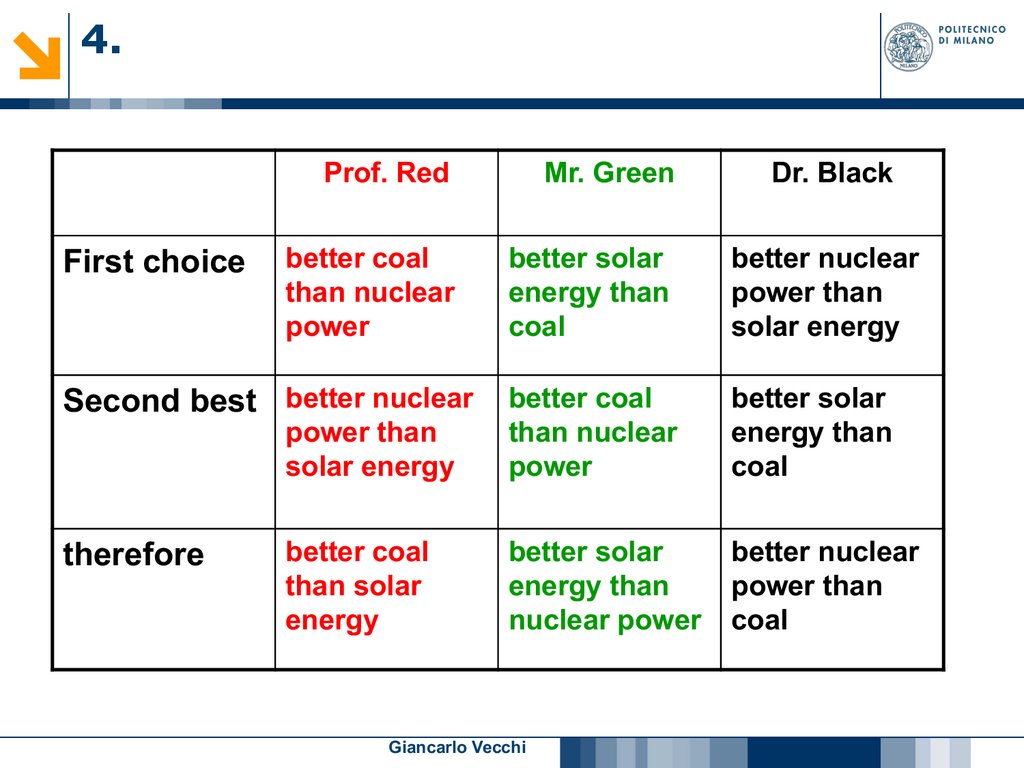

4.A committee is appointed to advise on

the best energy policy, composed by

§ Prof. Red – economist – maximises

efficiency

§ Mr. Green – environmentalist –

maximises sustainability

§ Dr. White – engineer – maximises

technology

Giancarlo Vecchi

25.

4.First choice

Prof. Red

Mr. Green

better coal

than nuclear

power

better solar

energy than

coal

better nuclear

power than

solar energy

power than

solar energy

better coal

than nuclear

power

better solar

energy than

coal

better coal

than solar

energy

better solar

energy than

nuclear power

better nuclear

power than

coal

Second best better nuclear

therefore

Giancarlo Vecchi

Dr. Black

26.

4.To learn

It is possible that collective preferences are

non-transitive (or cyclical)

Kennet Arrow has enlarged the paradox to

the “impossibility theorem” stating that it is

impossible to aggregate preference into a

single social welfare function under the

conditions of democracy

Giancarlo Vecchi

27.

5.c) The incremental model

Giancarlo Vecchi

28.

5.Charles Lindblom observed that often policy

making implies different groups with different

values and goals.

They are at the same time partisan and

interdependent.

In other words they have:

§ structurally conflicting goals

§ but they need each other

(example: majority/opposition,

politicians/bureaucrats, central

state/regional governments)

Giancarlo Vecchi

29.

5.§ Decision-makers do not follow the

synoptic method

§ Means (often) determine goals

(interdependence)

§ Only few alternatives are explored

and assessed

§ The assessment consists in a

comparison between the expected

change and the status quo

Giancarlo Vecchi

30.

5.§ An alternative is preferred if there is

an agreement among decisionmakers that this alternative is good

(i.e. acceptable)

§ The decision process is a partisan

mutual adjustment

§ Decisions are thus incremental, i.e.

departing as little as possible from the

status quo

Giancarlo Vecchi

31.

5.• In the incremental model the typical

decisional situation is not the one in which

all the actors seek to find the solution to a

specific problem.

Giancarlo Vecchi

32.

5.• On the contrary very often there is

- someone interested in solving the

problem,

- someone else only interested in

imposing their solution,

- someone interested in participating in

the process but not really keen in

solving the problem or adopting a

given solution, but only interested to

improve its role, or exchange the current

support with the support of the actors in

another decisional arena

Giancarlo Vecchi

33.

5.Lindblom, in the book “The intelligence

of democracy” (note the double

meaning), shows that this

“confusion” is really what democracy

is all about

Giancarlo Vecchi

34.

5.Objections to incrementalism

§ A conservative method

§ Not all interests are equally powerful

BUT

§ it is useful to explain decision making

processes at a micro-level

Giancarlo Vecchi

35.

5.STRATEGIES IF YOU ARE THE DESIGNER

You should prepare designs that have:

• one ‘core contents’, i.e. things that you do not

want to negotiate

• contents that you could change if a negotiation

will be required to reach a decision

• analyse the policy field to know the actors that

could be your partner and those that could be

your opponents, to understand why and which

changes you can accept

Giancarlo Vecchi

36.

6.The garbage can model

(Michael Cohen, James March e Johan

Olsen + John Kingdon)

Giancarlo Vecchi

37.

6.The garbage can model stresses the

anarchical nature of decision-making

processes as “loose collection of

ideas” as opposed to rational

“coherent structure”. Actors discover

preferences through action, rather

than act out of preferences.

Understandig is poor (problems are

complex), trial and error learning

operates, and participation is fluid.

Giancarlo Vecchi

38.

6.Decision-making arenas are collection

of choices which looks for problems

and issues and seeks decisional

situations in which they may be

advanced. Solutions looks for

problems. Choices thus compose a

“garbage can” into which various kind

of problems and solutions are

dumped by participants as they are

generated.

Giancarlo Vecchi

39.

6.§ Ambiguity, not only uncertainty

Factors of ambiguity

§ Actors’ preferences are not always fixed

and consistent

- rather they change during the

development of the process and, due

their interests and beliefs, not

necessarily coherent;

§ Actors’ participation is fluid

- people move in and out

- their attention is a scarce resource (it

depend on the period)

à

Giancarlo Vecchi

40.

6.(Factors of ambiguity)

§Solutions can come out also when

problems are not present yet

- there are problems in search of a

solution and solutions in search of a

problem (because they are supported

by different actors, because we can

use an available solution to deal with a

new problem, adapting it…)

§Problems and solutions can be presented

in several decisional venues, when actors

see choice opportunities

Giancarlo Vecchi

41.

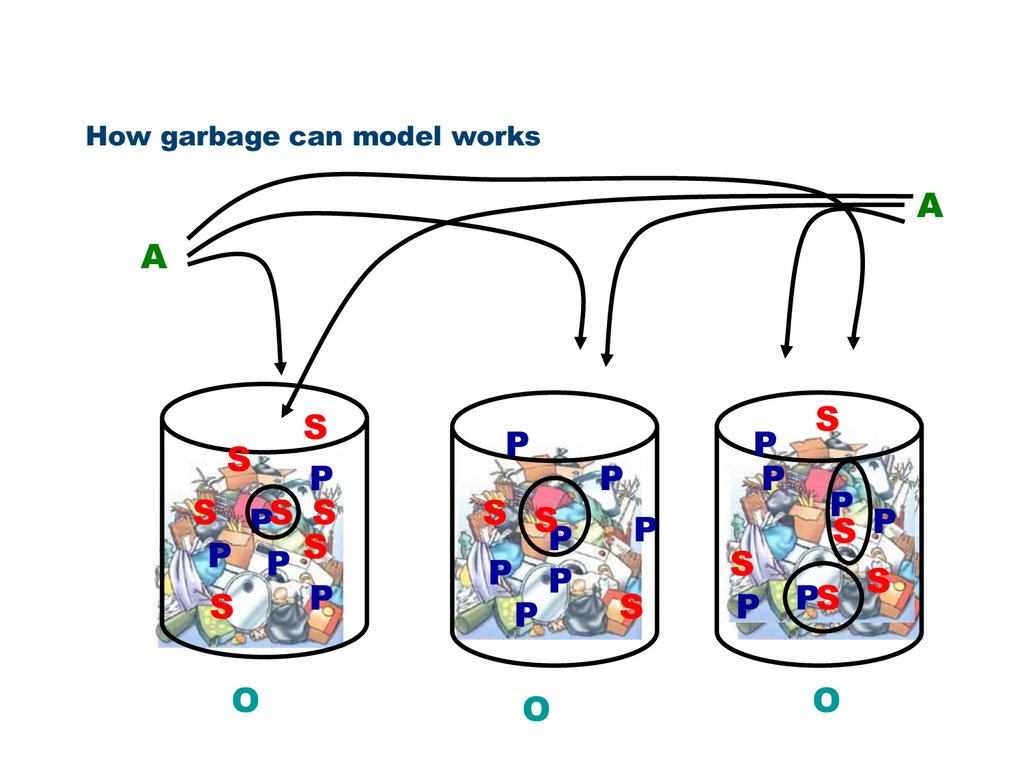

The four streams§

§

§

§

Actors (A)

Problems (P)

Solutions (S)

Choice Opportunities (O)

O are garbage cans in which A throw P and

S. The final decision will depend on the

casual matching of P and S.

42.

How garbage can model worksA

A

S

S

P

S PS S

P PS

P

S

O

P

S S

P

P P

P

O

P

P

P

P

S

S

P

S

P P

S

PS S

O

43.

6.In a garbage can process there are

exogenous, time-dependent arrivals of choice

opportunities, problems solutions and decision

makers. The logic of ordering is temporal

rather than hierarchical or consequential.

Problems and solutions are attached to

choices, and thus each other, not only

because of their means-end linkages but also

because of their simultaneity. (Cyert & March,

1992:25)

Giancarlo Vecchi

44.

6.The garbage can model argues that

• there are situations in which some

issues will have a solution attached

to them, and the coupled and

decided

• others will not,

• other solutions may be roaming

around looking for an issue to which

attach themselves.

Giancarlo Vecchi

45.

6.• ‘Policy entrepreneurs’ are actors interested in

reach a decision, and in the coupling

between problem and solutions:

“people who are willing to invest resources of

various kinds in hopes of future return in the

form of policies they favour”.

• They are crucial to the survival and success of

an idea: ideas must be technically feasible,

compatible with dominant values and able to

anticipate future constraints.

Giancarlo Vecchi

46.

6.STRATEGIES IF YOU ARE THE DESIGNER

You should have many proposal designed, a sort of

projects’ basin; it will be useful when a window

opportunity opens, and you will be ready to present

an appropriate proposal

You should know many decisional venues, to check

when a decisional processes starts there;

You should learn, during the process, if you should

change something to improve the opportunities for

your project or/and start a new partnership

Giancarlo Vecchi

47.

7.To sum up

Giancarlo Vecchi

48.

7.Model

Who decides

Evaluation Criteria

Individual

Predictive rationality:

Optimum

Individual/coalition

Retrospective Rationality:

Satisfaction

(eg: no losses, to win something)

incremental

Partisan interdependent

actors

Retrospective Rationality:

Mutual adjustment

(negotiate, constructing a coalition to

reach a decision)

garbage can

Changing actors and

positions depending on

arenas, problems and

learning from interactions

Retrospective Rationality:

Contingency

Entrepreneurship and capability to

connect problems and solutions in

open policy windows

rational

bounded rationality

Giancarlo Vecchi

49.

7.§

§

§

In the table going from the top to the bottom

decreases the prescriptive value and

increases the descriptive value

The prescriptions of the rational model are

strong and clear, but they are very difficult

to apply, while the prescriptions of the

garbage can model are universal but weak

and unclear

Which model? It depends on the situation

we have to tackle

Giancarlo Vecchi

50.

8. Uncertainty and decision makingDesigns as theories

If I adopt the measure x at the time t1 I will

get the result y at the time t2

But how can I know whether a causal link

between x and y exists?

This is the key problem of uncertainty

Giancarlo Vecchi

51.

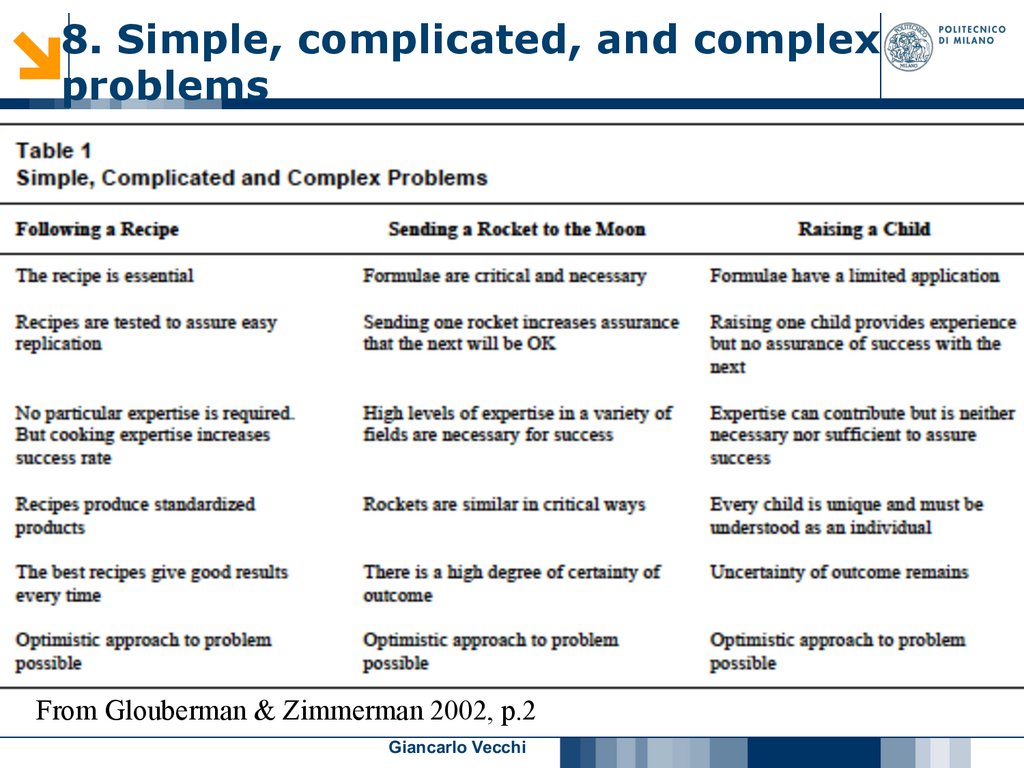

8. Simple, complicated, and complexproblems

S

From Glouberman & Zimmerman 2002, p.2

Giancarlo Vecchi

52.

8. Wicked problemsWicked problem: complex problems, that

characterize the activity of many social

professions: management, planning, etc.

Wicked: complex, interdependent, intractable,

conflict-prone

Examples?

Giancarlo Vecchi

53.

8.Wicked problem: complex problems, that

characterize the activity of many social

professions: management, planning, etc.

Wicked: complex, interdependent, intractable,

conflict-prone

e.g. environmental/ecological problem, climate

change, poverty, obesity/food,

health/pandemic, metropolitan

management, etc.

Giancarlo Vecchi

54.

8. Wicked problemsModern society is too pluralistic to tolerate artificial solutions

imposed on social groups with different attitudes and

values, and this pluralism undermines the possibility of

clear, agreed solutions.

The finite problems tackled by science and engineering are

seen as relatively ‘tame’ or ‘benign’ in the sense that their

elements are definable and solutions are verifiable

By contrast, modern social problems are generally ‘ill-defined’

and resistant to an agreed solution. They are therefore

‘wicked’, relying on political judgements rather than

scientific certitudes (Rittel & Webber, 1973: 160).

Giancarlo Vecchi

55.

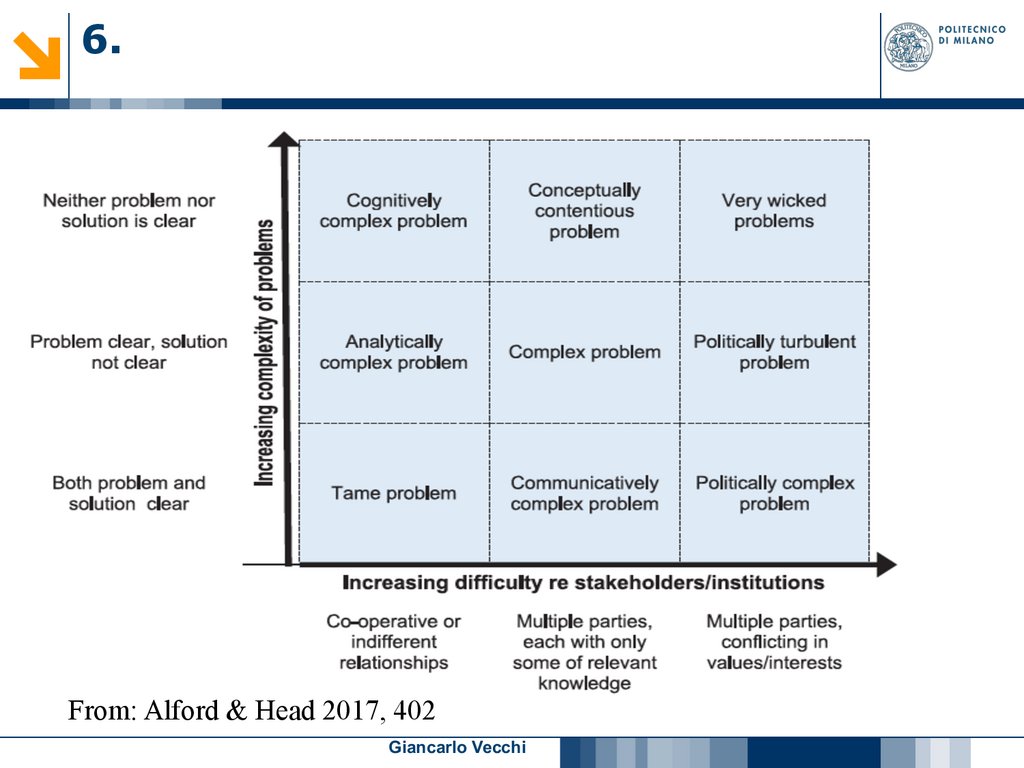

6.From: Alford & Head 2017, 402

Giancarlo Vecchi

56.

8.Two responses to uncertainty

§ Defeating uncertainty

§ more information, more solid theories, better

method

§ planning, rationality, etc.

§

Living with uncertainty

§ we must accept that often we have to make a

decision in the darkness, and try cope with it

§ incrementalism, negotiation, partisan adjustment,

trial and error

Giancarlo Vecchi

57.

8.Decisional strategies:

• Authoritative: one strong leader should decide with

authority. BUT: wicked problems by their nature are usually

beyond the cognitive capacity of any one mind to diagnose or

comprehend

• Competitive: fostering competition between societal actors to

come up with understandings of the problem and potential

advances in dealing with it. BUT: risk generating heightened

conflict that consumes resources and delays solutions.

• Collaboration: public consultation or participation in decisionmaking. BUT: how to pull this together into a coherent account

• Expert authority: again the nature of the problem is beyond

the thinking abilities of even the most erudite expert.

Giancarlo Vecchi

58.

8.OPPORTUNITY:

• Cooperation: we need strong cooperation among

different types of actors to work with different

resources. We need technical expertise, but it is

not the only type of capability required; also

needed is the capacity to lead, organise and

manage the cooperative processes, the exchange

of information, the implementation of responses,

etc.

Giancarlo Vecchi

59.

Thompson’s matrixGoals

Certain

1

Rational approach

Computation

Uncertain

Technologies

(means)

Certain

(agreement)

3

Trial and

error,

experiments

Uncertain

(disagreement)

2

Bargaining

4

Chaotic

Redefining

problem

60.

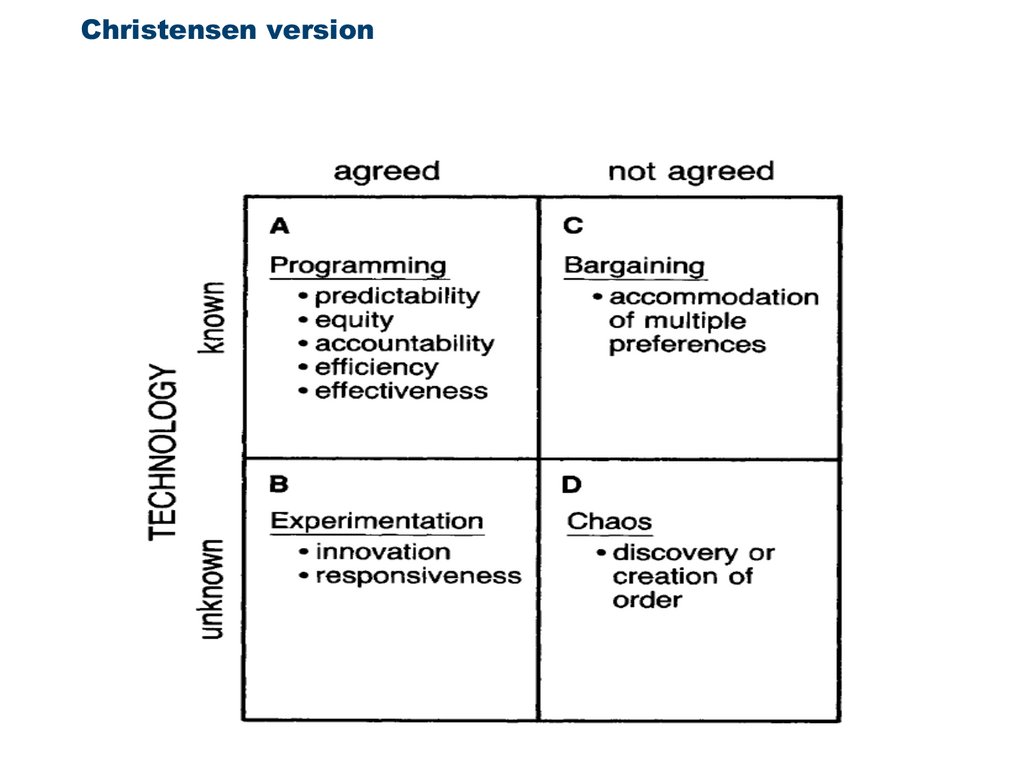

8.Thompson’s Matrix/2

• The matrix shows the approaches to follow on the

basis of two variables: technology (means) and

goals; and the level of uncertainty.

• Technology: do we know how to solve the

problem?

• Goals: do we agree about the characteristics of

the problem (the problem definition)?

Giancarlo Vecchi

61.

8.Thompson’s Matrix/3

Examples

Box 1: Vaccine to defeat cholera,

Box 2: Pensions, welfare system, etc.

Box 3: COVID-19? Car pollution,

Box 4: Immigration, poverty, COVID-19? Here: how to

redefine the problem?

Giancarlo Vecchi

62.

Christensen version63.

EXERCISE 2 –• Analyse

Менеджмент

Менеджмент