Похожие презентации:

Language and grammar

1. Language and grammar

«The rules controlling the way a communication system works are known asits grammar» (David Crystal, a British linguist)

Mastering the grammar of a foreign language is a conscious, reflective process.

1. Practical point of view: grammar is the art of language.

The main object - to help the student acquire mastery of the native or foreign

language. Practical grammar is prescriptive.

2. Theoretical point of view: grammar is the science of language.

The task - to provide an insight into the structure of the language under

examination in the light of the general principles of linguistics. Theoretical

grammar pursues analytical aims.

2.

Language is …• a complex, many-sided and many-functional phenomenon;

• social by nature; inseparably connected with the people who are its creators

and users; grows and develops together with the development of society;

• its definition depends upon what becomes the subject matter of research;

• has many aspects.

Three main aspects (ways of representing language):

1) language as a text (the result of speech activity, presented in the form of a

variety of speech products: literary texts, newspapers, interviews, various

documents, etc.);

2) language as a system (the result of linguistic research, reflected in

dictionaries, monographs, dissertations, devoted to various aspects of the

language and aiming to establish their systemic patterns);

3) language as a competence (language in the speaker’s mind i.e. knowledge of

the language and readiness to realize this knowledge).

3.

Definition of the language:a structured system of signs used for forming, storing and exchanging information

in the process of human communication.

It incorporates the three constituent parts ("sides"), each being inherent in it by

virtue of its social nature and the unity of which forms a language:

• the phonological system,

• the lexical system,

• the grammatical system.

The phonological system is the subfoundation of language; it determines the

material (phonetical) appearance of its significative units. The lexical system is

the whole set of naming means of language, that is, words and stable wordgroups. The grammatical system is the whole set of regularities determining the

combination of naming means in the formation of utterances as the embodiment

of thinking process [Blokh].

4.

The system of language includes the body of material units: sounds (phonemes),morphemes, words (lexemes), word-groups, sentences, supra-phrasal unities.

6 levels of linguistic analysis:

• Phonemic level: central unit – the phoneme, the smallest unit of language whose

function is to differentiate meanings. This level is closed, it comprises a limited set of

phonemes and it is relatively stable.

• Morphological level: constituted by morphemes – the smallest meaningful parts of

the language. The function of morphemes is either to build grammatical forms and

express grammatical meanings (formbuilding morphemes) or to derive new words

and express new lexical meanings (derivational, or wordbuilding morphemes).

• Lexemic level: central unit – the word. It presents the most open, densely populated

and the most changeable domain of any language.

• Phrasemic level: a combination of words results in the formation of its constituent –

a phrase.

• Proposemic (sentential) level: central unit – a sentence, which presents a complex

sign; it names not an object, but a situation of reality and forms a judgment (a

proposition) about this situation. The sentence fulfils not only a nominating function,

but a communicative one whereas words fulfill only a nominating function.

• Supra-proposemic (suprasentential) unit - a combination of at least two sentences

[Кожанов].

5. Language and speech

Systemic approach to language and its grammar - the Russian scholar Beaudoinde Courtenay and the Swiss scholar Ferdinand de Saussure:

• Difference between lingual synchrony (coexistence of lingual elements) and

diachrony (different time-periods in the development of lingual elements as

well as language as a whole)

• Language - a synchronic system of meaningful elements at any stage of its

historical evolution.

On the basis of discriminating synchrony and diachrony, the difference between

language proper and speech proper can be strictly defined, which is of crucial

importance for the identification of the object of linguistic science.

Language in the narrow sense of the word is a system of means of expression,

while speech should be understood as the manifestation of the system of

language in the process of intercourse.

6.

• The system of language includes the body of material units - sounds,morphemes, words, word-groups and the regularities or "rules" of the use of

these units.

• Speech comprises both the act of producing utterrances, and the utterances

themselves, i.e. the text.

Language and speech are inseparable, they form together an organic unity. As

for grammar (the grammatical system), being an integral part of the lingual

macrosystem it dynamically connects language with speech, because it

categorially determines the lingual process of utterance production.

Thus, we have broad philosophical concept of language which is analysed by

linguistics into two different aspects - the system of signs (language proper) and

the use of signs (speech proper). The generalizing term "language" is also

preserved in linguistics, showing the unity of these two aspects [Блох, 1986,

18].

The sign (meaningful unit) in the system of language has only a potential

meaning. In speech, the potential meaning of the lingual sign is "actualized",

i.e. made situationally significant as part of the grammatically organized text.

7.

Theoretical linguistic descriptions pursue analytical aims and thereforepresent the studied parts of language in relative isolation, so as to gain

insights into their inner structure and expose the intrinsic mechanisms of their

functioning.

Hence, the aim of theoretical grammar of a language is to present a

theoretical description of its grammatical system, i.e. to …

• scientifically analyze and define its grammatical categories,

• study the mechanisms of grammatical formation of utterances out of words

in the process of speech making [Blokh].

8. Grammar and its history

• The study of grammar goes back to the time of the ancient Greeks, Romans, andIndians

• In earlier periods of the development of linguistic knowledge, grammatical scholars

believed that the only purpose of grammar was to give strict rules of writing and

speaking correctly. Often subjective and arbitrary.

• Modern linguists take pains to set up their rules following a careful analysis of the

way the English language actually works.

II Periods:

I. Prescientific grammar (end of the 16th c.-1900): two types of grammars: early

descriptive and prescriptive. Early descriptive grammarians [e.g. William Bullokar]

merely described language phenomena. By the middle of the 18th c. descriptive

grammar gave way to prescriptive grammar [Robert Lowth], which stated strict rules of

grammatical usage.

II. Scientific grammar (end of the 19th с.): a need for a scientific explanation of the

grammatical phenomena. The appearance of Henry Sweet's grammar in 1891 met this

demand.

9.

Three chief methods of explaining language phenomena: 1) historical, 2) comparative,and 3) general grammar.

• Historical grammar tries to explain the phenomena of a language by studying their

history. Thus Old English nouns had gender, number, and case distinctions: three

grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter), two numbers (singular and

plural), and four cases (nominative, genitive, dative, and accusative).

The decay of noun inflections that began in the Middle English period is due to the

following:

• 1) the functional devaluation of inflections: some of their syntactic functions

came to be expressed by prepositions and word order, i.e. by analytical means;

• 2) the Scandinavian invasion. The two languages (English and Scandinavian) were

closely related. Since the roots of the words often sounded alike, the speakers

tended to ignore the inflections which hindered the process of communication.

The loss of inflections, which began in the Middle English period, resulted in the

disappearance of the grammatical category of gender and the reduction of the case

paradigm in Modern English to two forms: common and genitive.

10.

• Comparative grammar compares the grammatical phenomena of a languagewith those of cognate languages, i.e. languages that are related to it through

having arisen from a common parent language. Thus, the suppletive case

system of personal pronouns is common to all the languages of the IndoEuropean family. Cf.:

Russian: я - меня;

English: I-me;

German: ich - mich.

• General grammar is not concerned with the details of one language or a

family of languages, but with the general principles which underlie the

grammatical phenomena of all languages. Thus, all languages, according to

Joseph Harold Greenberg (am.), have pronominal categories involving at least

three persons and two numbers.

11.

The period of scientific grammar may be divided into two parts:1. from the appearance of H. Sweet's book - the 1940's. Two types of grammars:

prescriptive [J.C. Nesfield] and explanatory [C.T. Onions; H.R. Stokoe; G. Curme; H.

Poutsma; E. Kruisinga; O. Jespersen];

2. from the 1940's, when several new types of grammars appeared:

1) structural (descriptive) grammar [Ch. Fries]: aim - to give a formalized description

of language system as it exists, without being concerned with questions of correct

and incorrect usage.

2) transformational grammar [Z. Harris; N. Chomsky]: purpose - to show how

different sentences are derived from a few kernel sentences, e.g.:

• The door opened. — The door did open. — Did the door open?

3) communicatively orientated grammar [V. Mathesius; J. Firbas] studies the themerheme integration in a sentence. The theme is a part of a sentence seen as

corresponding to what the sentence as a whole, when uttered in a particular context, is

about. The rheme is a part of a sentence communicating information relative to

whatever is indicated by the theme.

E.g.: Our biggest problem (the theme) is lack of money (the rheme). (Longman

Language Activator)

12.

4) semantically orientated grammar [Ch.J. Fillmore; W.L. Chafe] concentratesits attention on the semantic structure of sentences.

5) pragmatically orientated grammar [J. Austin; J. Searle] focuses its attention

on the functional side of language units (speech act classification).

6) textual grammar places text in focus. The authors suggest different methods

of text analysis ranging from formal [Z. Harris] to semantic [T. van Dijk] and

pragmatic [V. Bogdanovj. The aims of the analysis are also different.

The authors of the first period [Z. Harris; V. Waterhouse] put forward the idea

of the dependence of the text type on the type of sentences making it up.

The authors of the second period [W. Hendricks; T. van Dijk] explore the text as

a whole and try to discover the lower units which constitute the given text.

M.A.K. Halliday makes an attempt at giving a theoretical basis of text grammar

[Прибыток].

13. THE PLANE OF CONTENT AND THE PLANE OF EXPRESSION

• The plane of content comprises the purely semantic elements contained inlanguage

• The plane of expression comprises the material (formal) units of language

taken by themselves, apart from the meanings rendered by them.

The two planes are inseparably connected, so that no meaning can be realized

without some material means of expression. Grammatical elements of language

present a unity of content and expression (a unity of form and meaning).

The relation between them is very complex (e.g.: the phenomena of polysemy,

homonymy, and synonymy), and peculiar to every language.

In cases of polysemy and homonymy, two or more units of the plane of content

correspond to one unit of the plane of expression.

• E.g.: I get up at half past six in the morning. I do see your point clearly now. As

a rational being, I hate war. (Present simple)

14.

• The morphemic material element -s/-es (in pronunciation [-s, -z, -iz]) (one unitin the plane of expression):

E.g.: John trusts his friends. We have new desks in our classroom. The chief’s

order came as a surprise.

• In cases of synonymy, conversely, two or more units of the plane of expression

correspond to one unit of the plane of content.

E.g.: Will you come to the party, too? Will you be coming to the party, too? Are

you coming to the party, too?

Taking into consideration the discrimination between the two planes, the

purpose of grammar as a linguistic discipline is to disclose and formulate the

regularities of the correspondence between the plane of content and the plane

of expression in the formation of utterances out of the stocks of words as part

of the process of speech production.

15. BRANCHES OF GRAMMAR. PARADIGMATIC VS SYNTAGMATIC RELATIONS

The field of grammar is generally divided into two domains:1. Morphology studies the grammatical structure of words and the categories

realized by them. Thus, a morphological analysis will divide the word girls

into the root girl and the inflection -s, which forms the plural.

2. Syntax studies the grammatical relations between words and other units

within the sentence.

Morphology - paradigmatic relations of morphemes and words.

Syntax - syntagmatic relations in phrases and sentences.

Syntagmatic relations are immediate linear relations between units in a

segmental sequence (string). Syntagmatically connected are words and wordgroups in the sentence, morphemes within words, phonemes within

morphemes and words. Syntax as a part of grammar studies syntagmatic

relations of words in phrases and sentences [Викулова, 2024].

16.

There are four main types of notional syntagmas identified in the sentence:E.g.: The small lady listened to me attentively.

1) predicative syntagma — The lady listened;

2) objective syntagma — listened to me;

3) attributive syntagma — The small lady;

4) adverbial syntagma — listened attentively.

Paradigmatic relations exist between elements of the system of language outside the

strings where they occur. Each linguistic unit is included in a set of connections based

on different properties. This is evident in classical grammatical paradigms which

express various grammatical categories (e. g. number, person, case, tense, aspect,

mood).

Morphology is a part of grammar which deals with the paradigmatic relations of wordforms. The major English verb paradigm includes 5 forms:

• 1) The Base Form (work).

• 2) The S-Form (works).

• 3) The ED-Form of the Past Simple (worked).

• 4) The ED-Form of the Past Participle (worked).

• 5) The ING-Form (working) [Викулова]

17. Morphology as a Part of Grammar

Chief notions of morphology:• grammatical form,

• grammatical category,

• word and

• morpheme.

H. Sweet: Tradition says that the difference between grammatical and lexical

meaning lies in the degree of the inherent abstraction. Lexical meaning is

considered to be concrete, grammatical meaning -abstract.

M.I. Steblin-Kamensky: it is not a higher degree of abstraction that differentiates

grammatical meaning from lexical meaning, for lexical meaning also represents

a generalized reflection of reality. Some lexical meanings, according to him, are

even more general than grammatical meanings (lexical meaning of the word

time vs. grammatical meanings of verbal tenses (present, past, or future).

18.

E.g.: the meanings of 'definiteness - indefiniteness‘In English: grammatical – articles serve the purpose of their realization.

In Russian: lexical – no constant grammatical means to express these meanings.

M.I. Sieblin-Kamensky: grammatical and lexical meanings should be

differentiated with regard to thought.

• Lexical meanings form the basis of thought; hence, they are independent.

• Grammatical meanings organize thought; hence, they are dependent on the

lexical meanings they accompany.

Each part of speech has a specific set of grammatical meanings.

The English noun: number and case,

The adjective: degrees of comparison.

19.

The grammatical form - the sum total of all the formal means constantlyemployed to render this or that grammatical meaning.

K. Pike and A.V. Bondarko qualify the sum total of grammatical means used to

convey a certain grammatical meaning as a grammeme.

For instance:

• the present tense grammeme comprises the zero exponent* for the first and

second person singular and plural and the third person plural and the

inflection -(e)s for the third person singular. (*meaningful absence of any

outward sign which serves the purpose of rendering some grammatical

meaning when opposed to forms with positive inflections.).

• The past tense grammeme comprises the inflection -(e)d for regular verbs and

vowel change, consonant change, etc. for irregular verbs.

• The future tense grammeme comprises the analytical combination of the

infinitive with the auxiliary verb -will.

20.

Homogeneous grammemes, i.e. grammemes possessing a common generalizedgrammatical meaning, build up a grammatical category.

Thus, the generalized grammatical meaning of tense, lying at the basis of the

present, past, and future tense grammemes, generates the grammatical

category of tense.

A.V. Bondarko: the notions 'grammatical form', 'grammeme', and 'grammatical

category' build up a three-level hierarchy:

The grammatical form as the lowest ladder on the rank scale →

The grammeme as a unity of homogeneous grammatical forms →

The grammatical category as a unity of homogeneous grammemes.

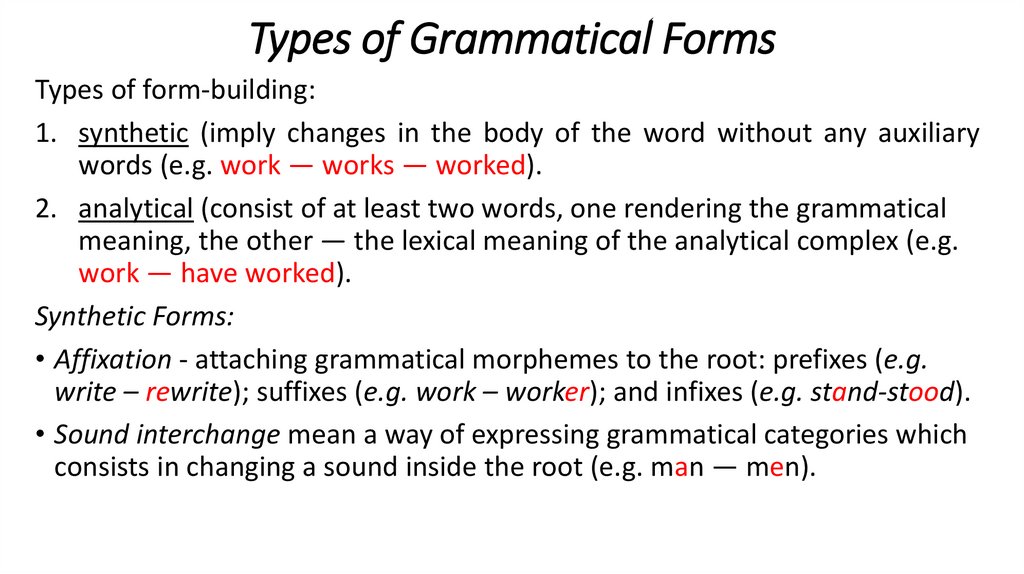

21. Types of Grammatical Forms

Types of form-building:1. synthetic (imply changes in the body of the word without any auxiliary

words (e.g. work — works — worked).

2. analytical (consist of at least two words, one rendering the grammatical

meaning, the other — the lexical meaning of the analytical complex (e.g.

work — have worked).

Synthetic Forms:

• Affixation - attaching grammatical morphemes to the root: prefixes (e.g.

write – rewrite); suffixes (e.g. work – worker); and infixes (e.g. stand-stood).

• Sound interchange mean a way of expressing grammatical categories which

consists in changing a sound inside the root (e.g. man — men).

22.

• Analytical FormsThe analytical form - a unity of a notional word and an auxiliary word. In the

opinion of L.S. Barkhudarov and D.A. Shteling, the first component in the

analytical form is devoid of lexical meaning, the second has lost its grammatical

characteristics.

• Suppletive formation

Suppletive formation is a way of building a form of a word from an altogether

different stem (e.g. go - went).

Grammatical category - a system of expressing a generalized grammatical

meaning by means of paradigmatic correlation of grammatical forms (e.g. the

category of number in nouns with the singular and plural forms).

Grammatical categories represent systems of grammemes with homogeneous

generalized grammatical meaning.

A.V. Bondarko: not only as a system but also a property of a certain part of

speech. E.g.: the grammatical category of number is a property of the noun; the

grammatical category of tense is a property of the verb, etc.

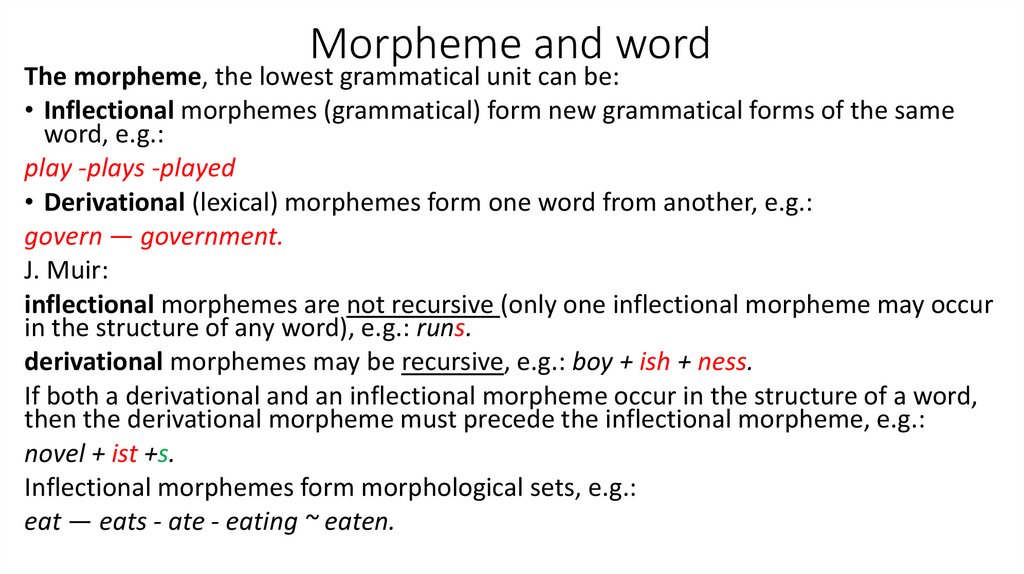

23. Morpheme and word

The morpheme, the lowest grammatical unit can be:• Inflectional morphemes (grammatical) form new grammatical forms of the same

word, e.g.:

play -plays -played

• Derivational (lexical) morphemes form one word from another, e.g.:

govern — government.

J. Muir:

inflectional morphemes are not recursive (only one inflectional morpheme may occur

in the structure of any word), e.g.: runs.

derivational morphemes may be recursive, e.g.: boy + ish + ness.

If both a derivational and an inflectional morpheme occur in the structure of a word,

then the derivational morpheme must precede the inflectional morpheme, e.g.:

novel + ist +s.

Inflectional morphemes form morphological sets, e.g.:

eat — eats - ate - eating ~ eaten.

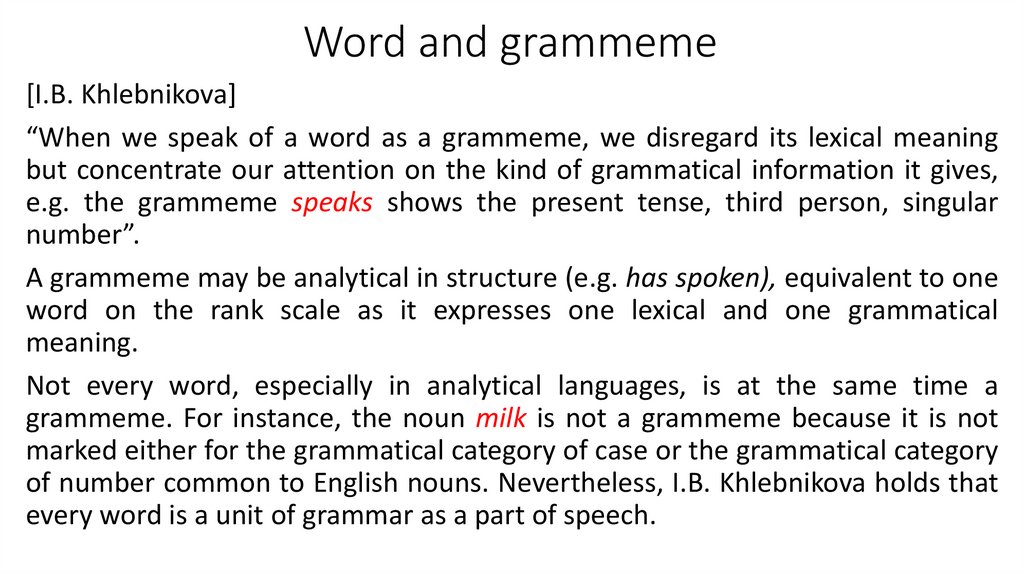

24. Word and grammeme

[I.B. Khlebnikova]“When we speak of a word as a grammeme, we disregard its lexical meaning

but concentrate our attention on the kind of grammatical information it gives,

e.g. the grammeme speaks shows the present tense, third person, singular

number”.

A grammeme may be analytical in structure (e.g. has spoken), equivalent to one

word on the rank scale as it expresses one lexical and one grammatical

meaning.

Not every word, especially in analytical languages, is at the same time a

grammeme. For instance, the noun milk is not a grammeme because it is not

marked either for the grammatical category of case or the grammatical category

of number common to English nouns. Nevertheless, I.B. Khlebnikova holds that

every word is a unit of grammar as a part of speech.

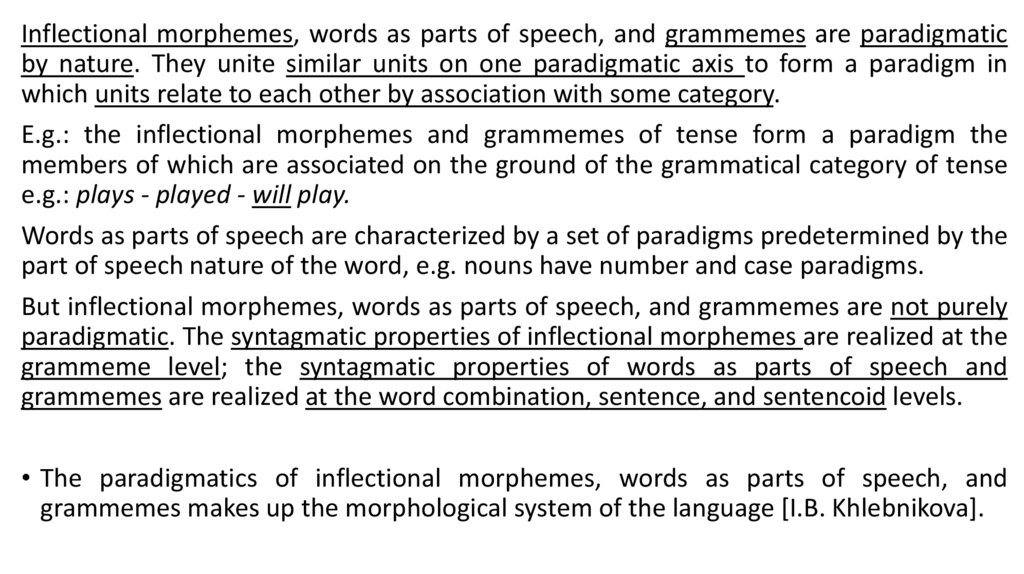

25.

Inflectional morphemes, words as parts of speech, and grammemes are paradigmaticby nature. They unite similar units on one paradigmatic axis to form a paradigm in

which units relate to each other by association with some category.

Е.g.: the inflectional morphemes and grammemes of tense form a paradigm the

members of which are associated on the ground of the grammatical category of tense

e.g.: plays - played - will play.

Words as parts of speech are characterized by a set of paradigms predetermined by the

part of speech nature of the word, e.g. nouns have number and case paradigms.

But inflectional morphemes, words as parts of speech, and grammemes are not purely

paradigmatic. The syntagmatic properties of inflectional morphemes are realized at the

grammeme level; the syntagmatic properties of words as parts of speech and

grammemes are realized at the word combination, sentence, and sentencoid levels.

• The paradigmatics of inflectional morphemes, words as parts of speech, and

grammemes makes up the morphological system of the language [I.B. Khlebnikova].

26.

• Stem, or base, is the part of a word which remains unchanged throughout itsparadigm. The most characteristic feature of word structure in Modern English is

the phonetic identity of the stem with the root morpheme.

• The root-morpheme is the common part within a word-cluster and the lexical

centre of the word. Root-morphemes make the subject of lexicology. Derivational

morphemes are lexically dependent on the root-morphemes, which they modify.

But most of them have the part-of-speech meaning, which makes them

grammatically significant. Inflectional morphemes have no lexical meaning.

Inflections (endings) carry only grammatical meaning (of such categories as person,

number, case, tense, aspect, etc).

• Allomorphs, or morphs, are all the representations of the given morpheme, in

other words, the morpheme phonetic variants (e.g. please, pleasant, pleasure; or

else, poor, poverty).

• “Zero-morpheme” shows that the absence of a morpheme indicates a certain

grammatical meaning (e.g. book vs. books).

• Zero-morpheme does not have any sound form. To avoid this contradiction, some

scholars suggest that the term should be changed and the meaningful absence of a

morpheme should be termed “zero-exponent”.

Английский язык

Английский язык