Похожие презентации:

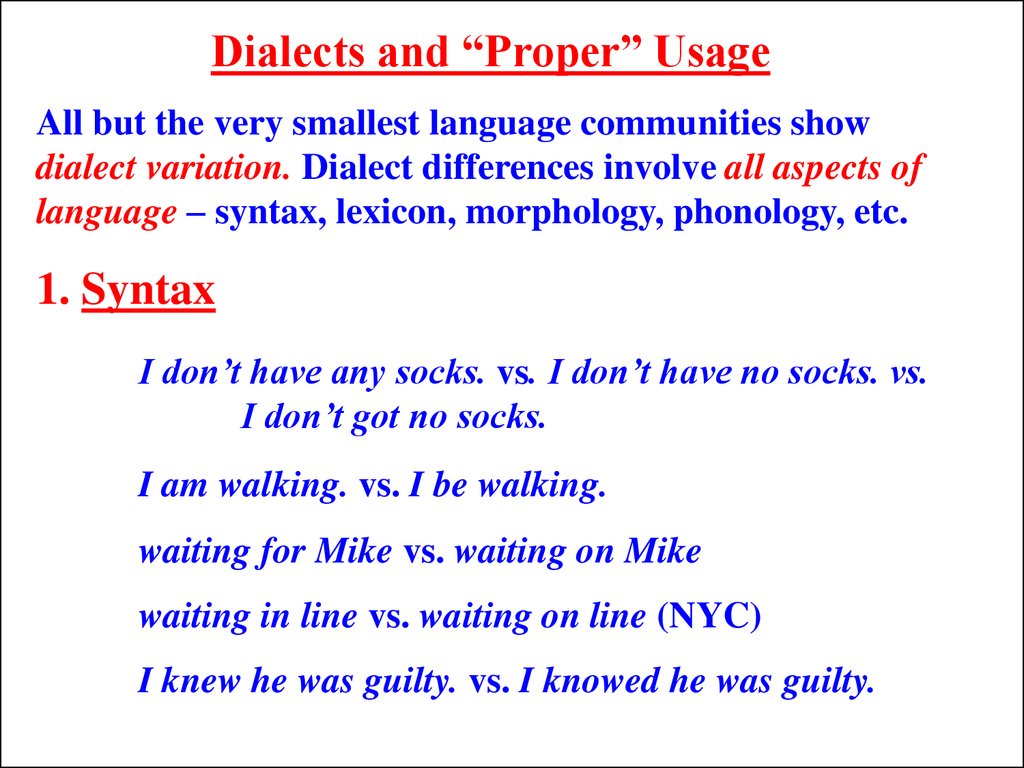

Dialect, all aspects of language – syntax, lexicon, morphology, phonology

1.

Dialects and “Proper” UsageAll but the very smallest language communities show

dialect variation. Dialect differences involve all aspects of

language – syntax, lexicon, morphology, phonology, etc.

1. Syntax

I don’t have any socks. vs. I don’t have no socks. vs.

I don’t got no socks.

I am walking. vs. I be walking.

waiting for Mike vs. waiting on Mike

waiting in line vs. waiting on line (NYC)

I knew he was guilty. vs. I knowed he was guilty.

2.

2. Phonology/phoneticsListen especially for “north” of “north wind,”

“warmly,” “other” in “stronger than the other.” Any

guesses about what region this speaker might be

from?

Note “north,” “longer,” “stronger,” “first,”

“warmly”, “at last.” Variety of English?

What region of the U.S. do you suppose this person is

from?

Where’s this guy from?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vYabrQrXt4A

3.

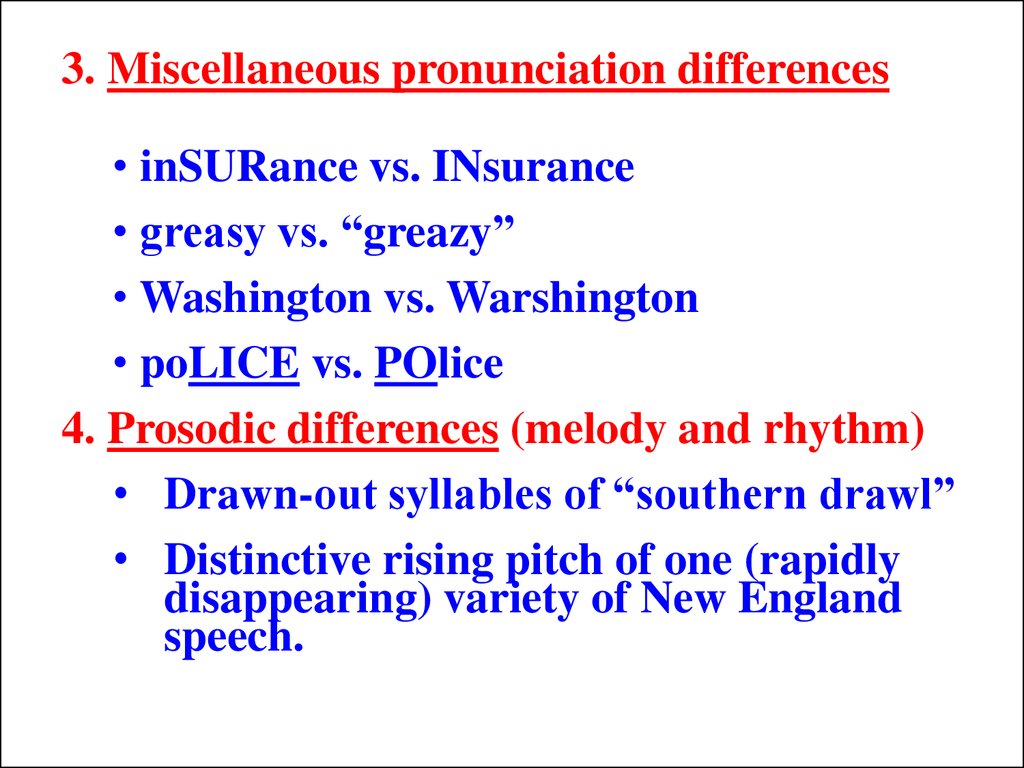

3. Miscellaneous pronunciation differences• inSURance vs. INsurance

• greasy vs. “greazy”

• Washington vs. Warshington

• poLICE vs. POlice

4. Prosodic differences (melody and rhythm)

• Drawn-out syllables of “southern drawl”

• Distinctive rising pitch of one (rapidly

disappearing) variety of New England

speech.

4.

New prosodic feature associatedwith dialect variation: Up-talking

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tj4EIGje4dA

5.

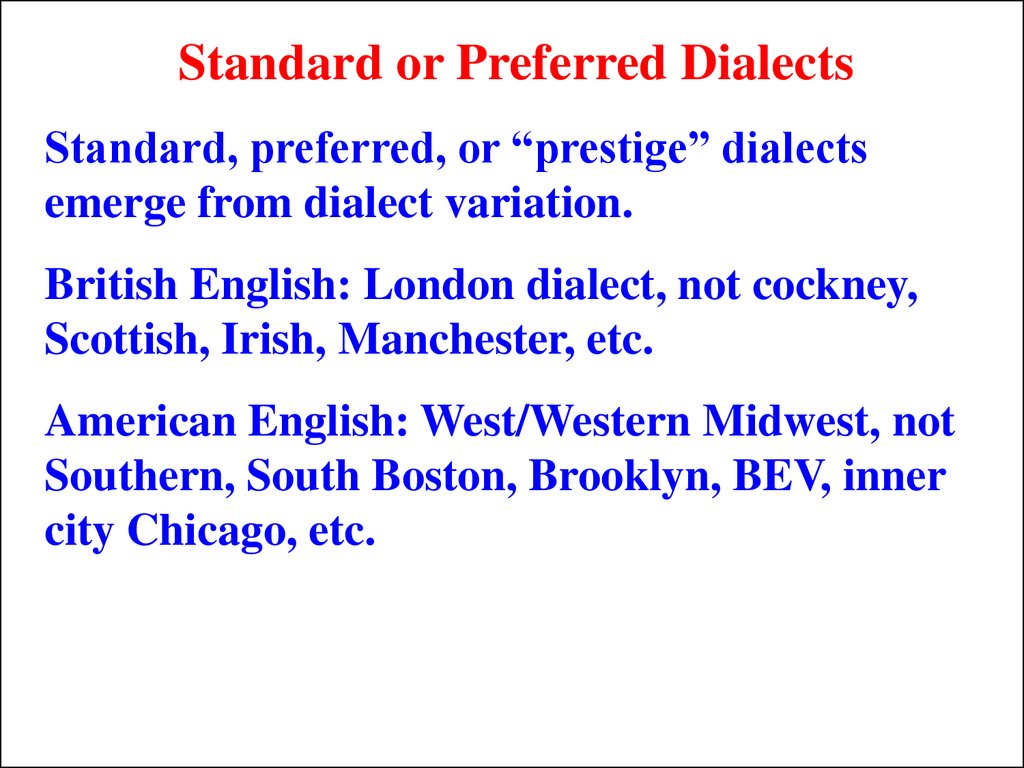

Standard or Preferred DialectsStandard, preferred, or “prestige” dialects

emerge from dialect variation.

British English: London dialect, not cockney,

Scottish, Irish, Manchester, etc.

American English: West/Western Midwest, not

Southern, South Boston, Brooklyn, BEV, inner

city Chicago, etc.

6.

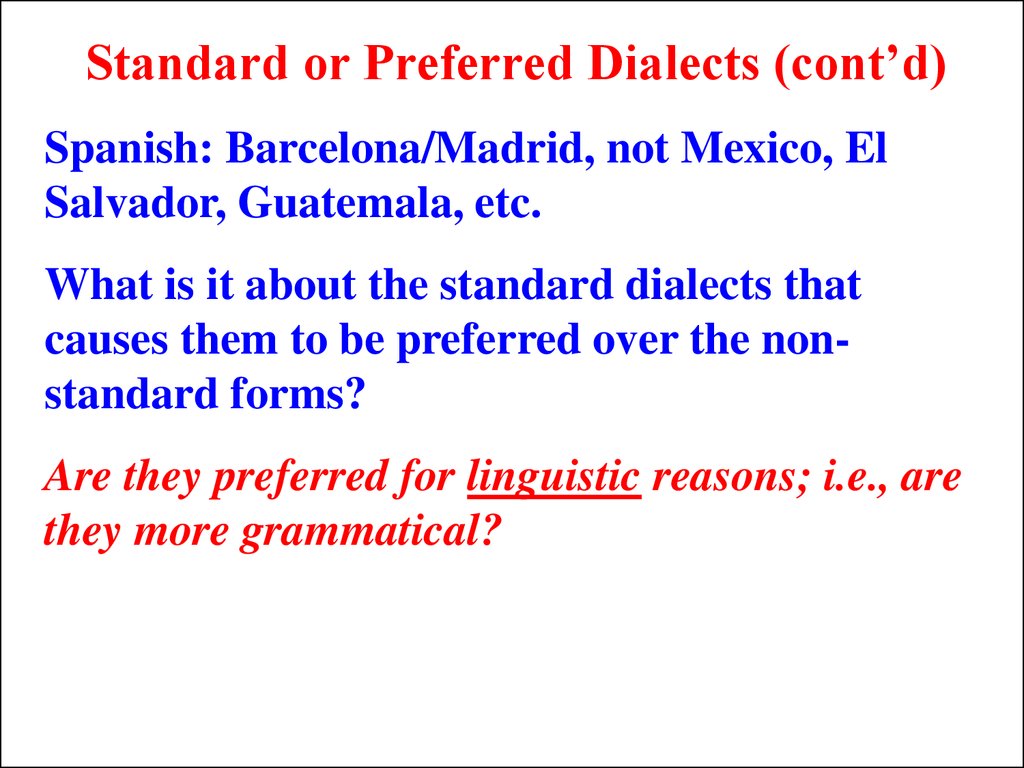

Standard or Preferred Dialects (cont’d)Spanish: Barcelona/Madrid, not Mexico, El

Salvador, Guatemala, etc.

What is it about the standard dialects that

causes them to be preferred over the nonstandard forms?

Are they preferred for linguistic reasons; i.e., are

they more grammatical?

7.

Opinions vary. This is from John Simon (theater critic,language guru)

“Why should we consider some, usually poorly

educated, subculture’s notion of the relationship

between sound and meaning? … As for ‘I be,’ ‘you be,’

‘he be,’ etc., … these may indeed be comprehensible,

but they go against all accepted classical and modern

grammars and are the product not of a language with

roots in history but of ignorance of how language

works.”

And this:

“The English language is being treated nowadays exactly as slave

traders once handled the merchandise in their slave ships, or as the

inmates of concentration camps were dealt with by their Nazi jailers.”

8.

Yikes! Position is pretty clear: SE is preferred on purelylinguistic grounds: “I am” has its roots in accepted classical

grammar; “I be” has its roots in ignorance.

Another view – linguist Dwight Bollinger:

“In language there are no licensed practitioners, but the woods

are full of midwives, herbalists, colonic irrigationists, bonesetters,

and general-purpose witch doctors, some abysmally ignorant …

whom we shall call shamans [read: John Simon and his fellow

language mavens] ... We are living in an African village and

Albert Schweitzer has not arrived yet.”

9.

One more view: Linguist Stephen Pinker“Most of the prescriptive rules of the language mavens

[i.e., shamans] make no sense on any level. They are bits of

folklore that originated for screwball reasons several

hundred years ago and have perpetuated themselves ever

since … The rules conform neither to logic nor to tradition

… Indeed, most of the ‘ignorant errors’ these rules are

supposed to correct display an elegant logic and an acute

sensitivity to the grammatical texture of the language, to

which the language mavens are oblivious.”

10.

These views could hardly be more different. Who’s right? Thelanguage mavens or the linguists?

Short answer: the linguists. No doubt about it.

Arguments in a minute, but if we accept (for the moment)

that there are no linguistic grounds for preferring the

standard, how do standard dialects become preferred?

Answer is very simple: standard dialects are those that we

associated with geographic centers of wealth and political

power.

British English: Why London and not Manchester or

Liverpool?

Spanish: Why Barcelona and not Guatemala or Puerto Rico?

American English: Why this broad swath from the upper

Midwest to the west coast and not Brooklyn, rural

Mississippi, south Boston, south-side Chicago (Sipowitz), East

St. Louis, urban Detroit, rural Appalachia, rural Arkansas?

11.

One more wrinkle: It’s too simplistic to say that there is a singlepreferred dialect – “cultivated” or “aristocratic” southern

speech patterns are quite well accepted (Trent Lott

[Mississippi], Robert Byrd [WVa], Sam Nunn [Georgia], etc.).

So are some “educated” NYC dialects: Mario Cuomo, Rudy

Guliani. Compare these 2 southern dialects:

Neither speech pattern conforms to “General American,” and

both are distinctively “southern,” but which of these would you

suppose is more accepted? Why?

So, what are the common threads among the dialect “haves” vs.

the “have nots”? Simple: Money, political power.

Are there any counter-examples; e.g., a language in which the

standard dialect was associated not with Madrid but with

Honduras or El Salvador?

12.

Is it really true that there are no linguistic grounds forpreferring the standard dialect?

I don’t have no twinkies.

This one has to be messed up, doesn’t it? Two

negatives make a positive! It’s just not logical. It does

violence to the language – just like the Nazis. Guess

what? Many languages do this. French:

Je ne sais pas.(“I do not know.”; literally, “I not know not.”)

Yikes – ne negates, pas negates. It’s a dreaded double

negative.

Spanish has a very similar construction. Many

languages do. Why shouldn’t English? Answer: It

does, but not in standard English.

13.

Proper construction is supposed to be:I don’t have any Twinkies.

The any here turns out to function strictly as a grammatical

place holder. How do we know? Can’t be used alone:

*I have any twinkies. ???

The any here serves a place holder function in the same way

as the it of “It is raining.” The “no” of “I don’t have no

twinkies” fulfills this grammatical function just as well as

“any.”

Last point: In the world of grammar, two negatives do not

make a positive. Do these sentences mean the same thing?

He is attractive. [This is good news right?]

He is not unattractive. [A polite way to say, “He’s a gargoyle.”]

14.

Here’s another one: Don’t split infinitives (e.g., to go).… to boldly go where no man has gone before …

boldy has intruded in the middle of to go. Here’s the

educated way:

… to go boldly where no man has gone before …

Yech. Any idea where this “rule” came from?

Latin!!!!

dare (to give), docere (to teach), contare (to sing)

Reasoning (?): (1) Latin doesn’t split infinitives, (2)

Latin is way cool, (3) English speakers (if they want to

be way cool) shouldn’t split infinitives.

15.

This entirely idiotic “usage rule” is well over 100 yearsold. It makes absolutely no sense whatsoever. None.

The pinhead who came up with it managed to

convince people to apply a feature of Latin to English.

How was he able to pull this off? Easy – he declared

himself to be a language expert, and readers of his

usage manual thought, ok, he’s the expert. I’m going

to follow this rule, then people will know that I’m way

educated.

16.

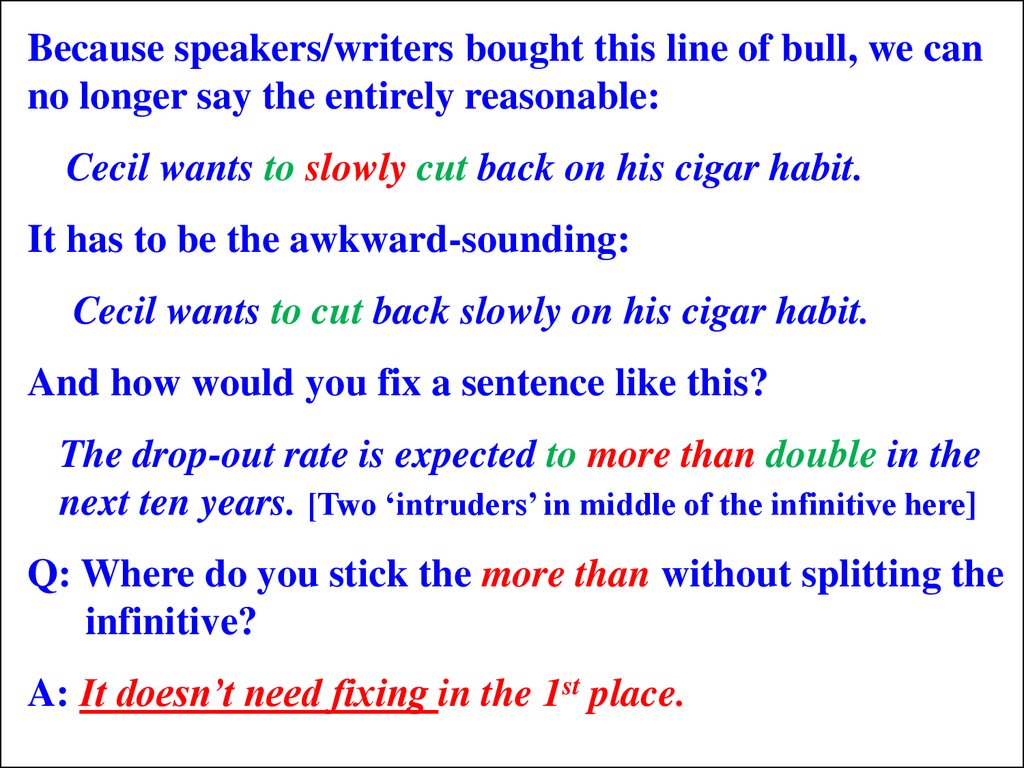

Because speakers/writers bought this line of bull, we canno longer say the entirely reasonable:

Cecil wants to slowly cut back on his cigar habit.

It has to be the awkward-sounding:

Cecil wants to cut back slowly on his cigar habit.

And how would you fix a sentence like this?

The drop-out rate is expected to more than double in the

next ten years. [Two ‘intruders’ in middle of the infinitive here]

Q: Where do you stick the more than without splitting the

infinitive?

A: It doesn’t need fixing in the 1st place.

17.

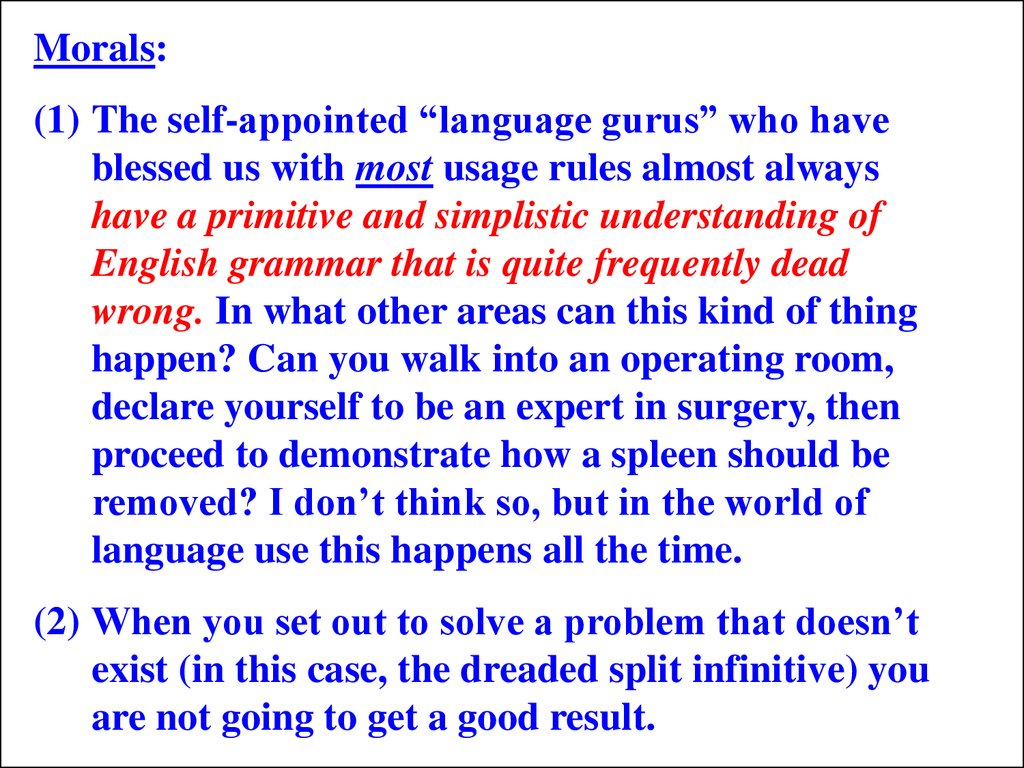

Morals:(1) The self-appointed “language gurus” who have

blessed us with most usage rules almost always

have a primitive and simplistic understanding of

English grammar that is quite frequently dead

wrong. In what other areas can this kind of thing

happen? Can you walk into an operating room,

declare yourself to be an expert in surgery, then

proceed to demonstrate how a spleen should be

removed? I don’t think so, but in the world of

language use this happens all the time.

(2) When you set out to solve a problem that doesn’t

exist (in this case, the dreaded split infinitive) you

are not going to get a good result.

18.

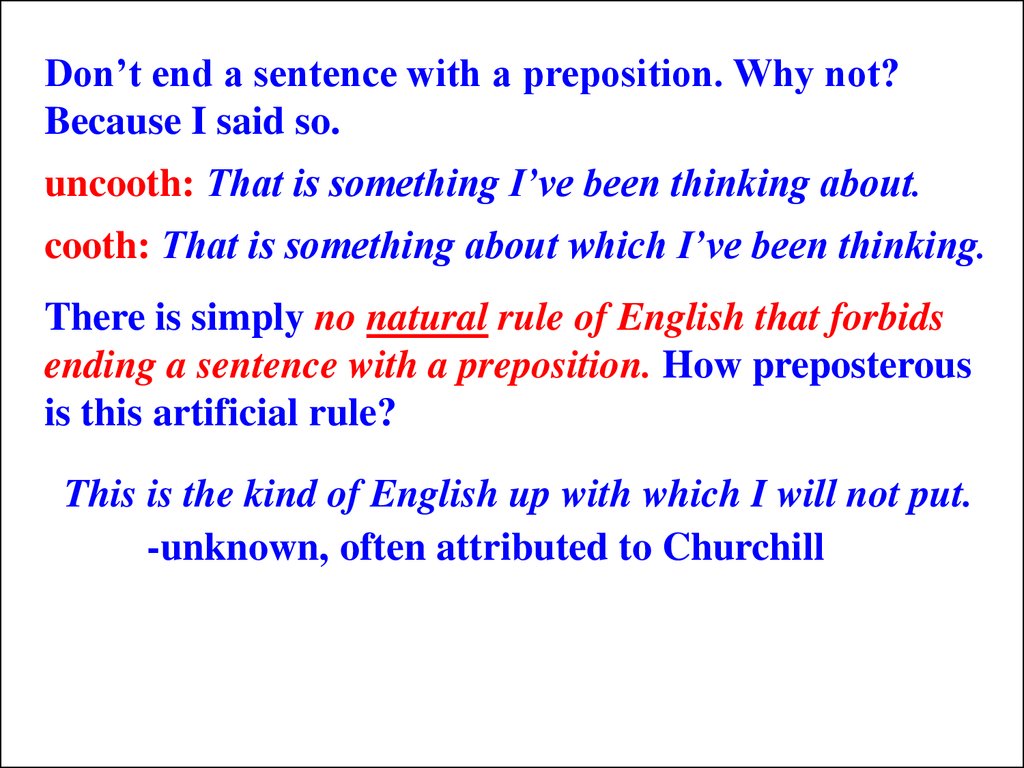

Don’t end a sentence with a preposition. Why not?Because I said so.

uncooth: That is something I’ve been thinking about.

cooth: That is something about which I’ve been thinking.

There is simply no natural rule of English that forbids

ending a sentence with a preposition. How preposterous

is this artificial rule?

This is the kind of English up with which I will not put.

-unknown, often attributed to Churchill

19.

How would you fix this one?Tennis is the game I’ve been playing around with.

There are two prepositions at the end. How to fix it?

How about:

*Tennis is the game around with which I’ve been playing.

Sound OK? I don’t think so. It could be completely

reworded from scratch – but why? There’s nothing wrong

with it.

20.

NOTE: This next example, which has todo a bogus usage rule involving the word

hopefully, is the single best example that I

have.

If you understand this example you’ll

understand what the whole usage-rule

mess is all about.

There isn’t anything difficult about it.

21.

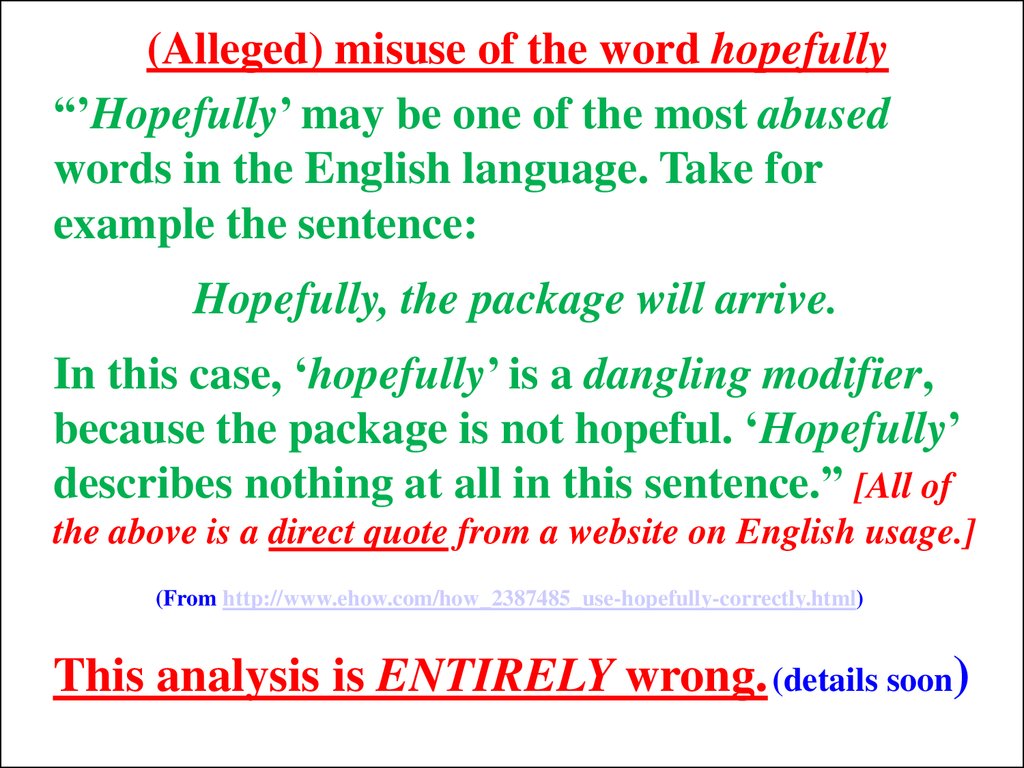

(Alleged) misuse of the word hopefully“’Hopefully’ may be one of the most abused

words in the English language. Take for

example the sentence:

Hopefully, the package will arrive.

In this case, ‘hopefully’ is a dangling modifier,

because the package is not hopeful. ‘Hopefully’

describes nothing at all in this sentence.” [All of

the above is a direct quote from a website on English usage.]

(From http://www.ehow.com/how_2387485_use-hopefully-correctly.html)

This analysis is ENTIRELY wrong. (details soon)

22.

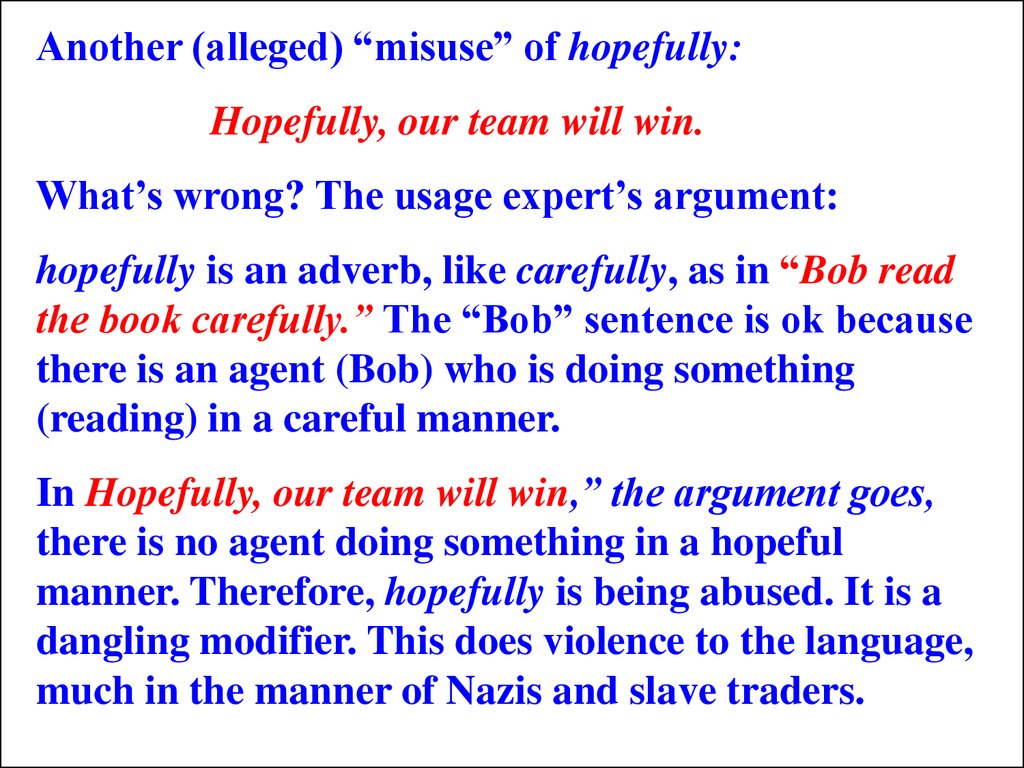

Another (alleged) “misuse” of hopefully:Hopefully, our team will win.

What’s wrong? The usage expert’s argument:

hopefully is an adverb, like carefully, as in “Bob read

the book carefully.” The “Bob” sentence is ok because

there is an agent (Bob) who is doing something

(reading) in a careful manner.

In Hopefully, our team will win,” the argument goes,

there is no agent doing something in a hopeful

manner. Therefore, hopefully is being abused. It is a

dangling modifier. This does violence to the language,

much in the manner of Nazis and slave traders.

23.

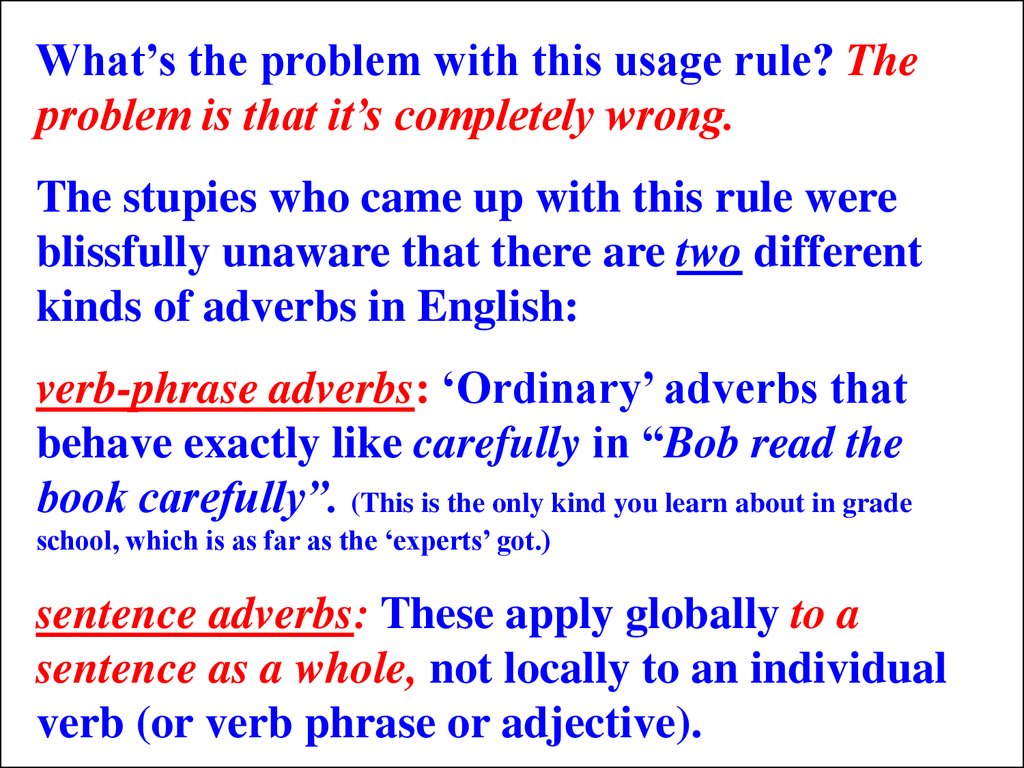

What’s the problem with this usage rule? Theproblem is that it’s completely wrong.

The stupies who came up with this rule were

blissfully unaware that there are two different

kinds of adverbs in English:

verb-phrase adverbs: ‘Ordinary’ adverbs that

behave exactly like carefully in “Bob read the

book carefully”. (This is the only kind you learn about in grade

school, which is as far as the ‘experts’ got.)

sentence adverbs: These apply globally to a

sentence as a whole, not locally to an individual

verb (or verb phrase or adjective).

24.

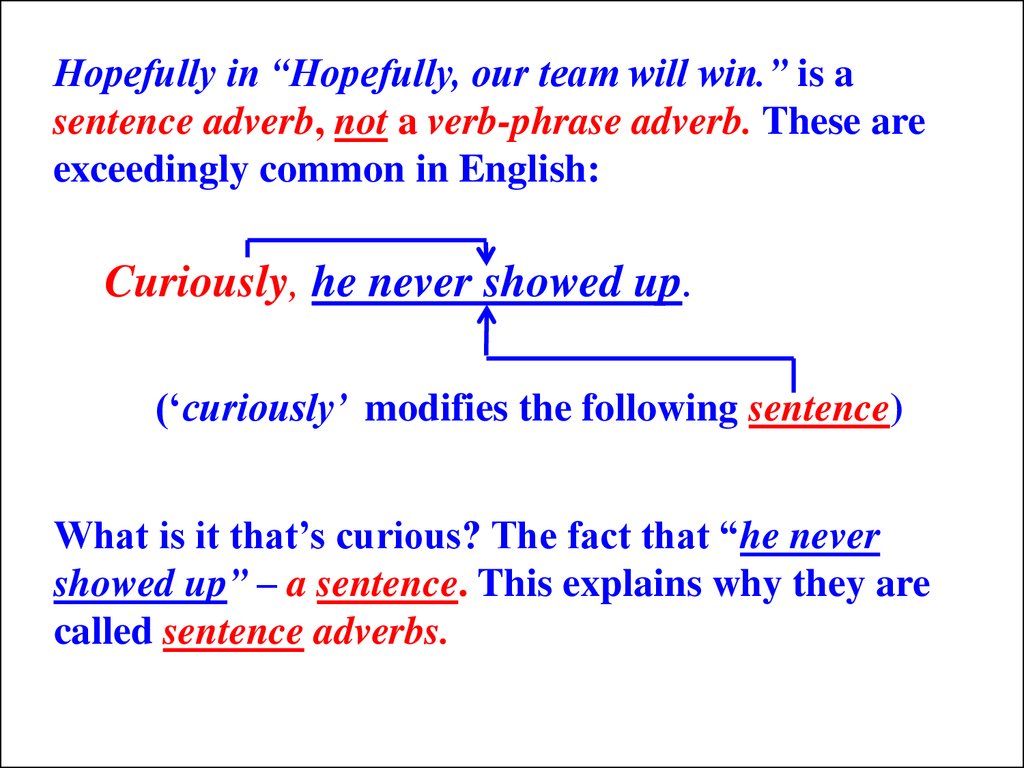

Hopefully in “Hopefully, our team will win.” is asentence adverb, not a verb-phrase adverb. These are

exceedingly common in English:

Curiously, he never showed up.

(‘curiously’ modifies the following sentence)

What is it that’s curious? The fact that “he never

showed up” – a sentence. This explains why they are

called sentence adverbs.

25.

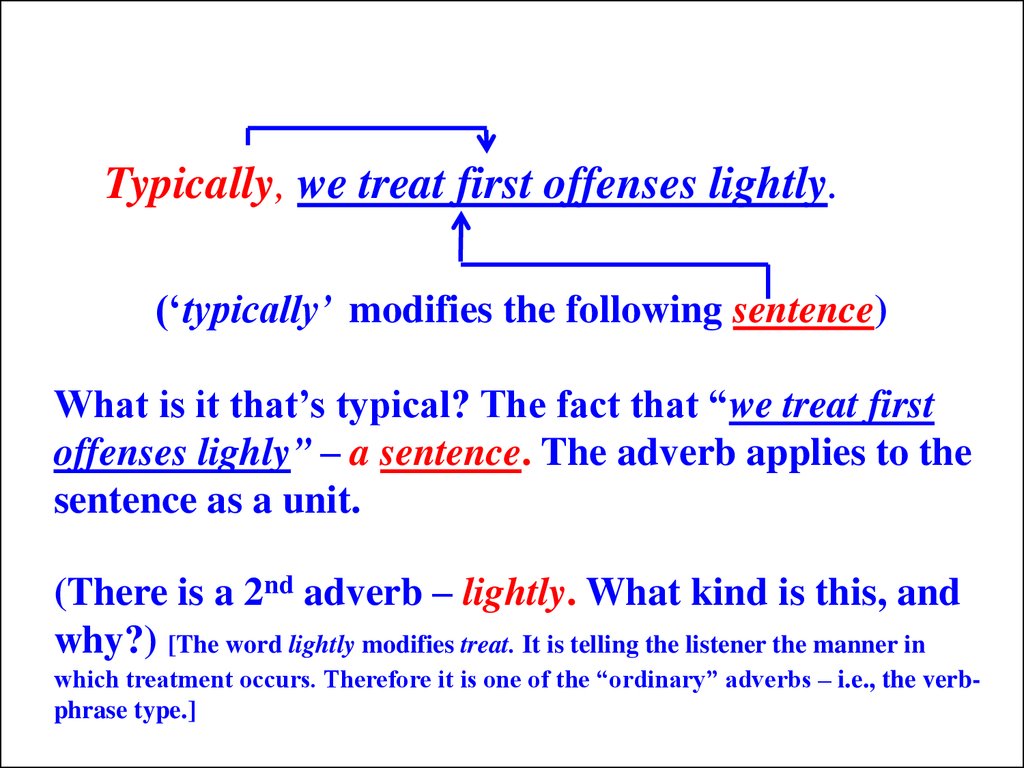

Typically, we treat first offenses lightly.(‘typically’ modifies the following sentence)

What is it that’s typical? The fact that “we treat first

offenses lighly” – a sentence. The adverb applies to the

sentence as a unit.

(There is a 2nd adverb – lightly. What kind is this, and

why?) [The word lightly modifies treat. It is telling the listener the manner in

which treatment occurs. Therefore it is one of the “ordinary” adverbs – i.e., the verbphrase type.]

26.

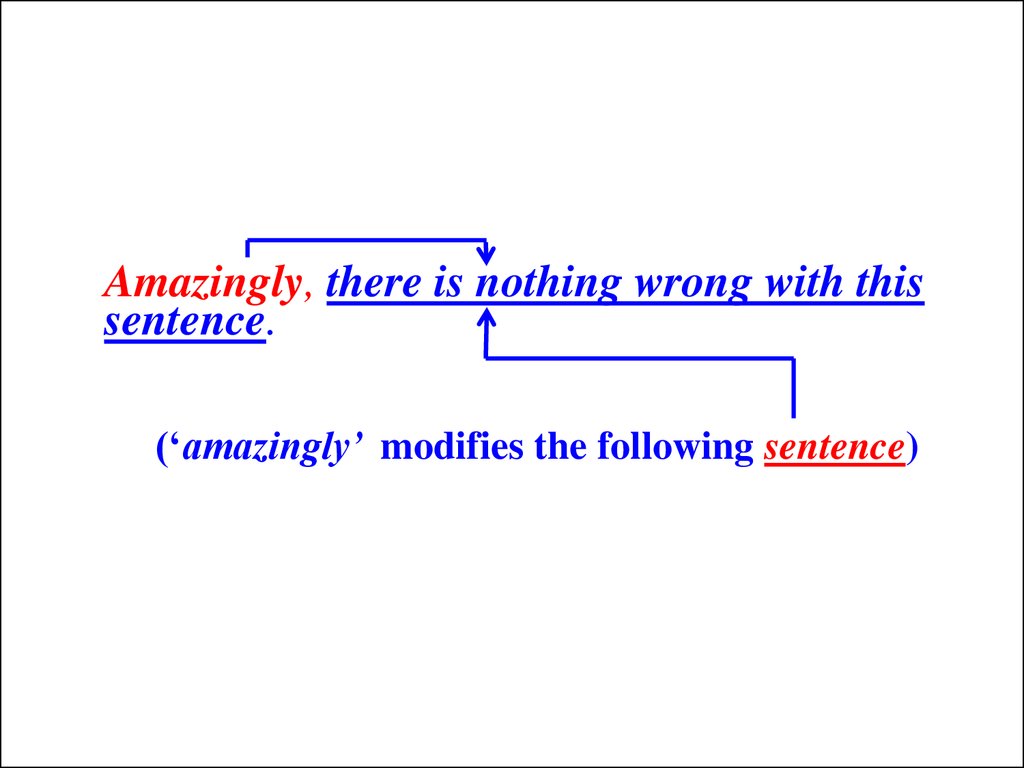

Amazingly, there is nothing wrong with thissentence.

(‘amazingly’ modifies the following sentence)

27.

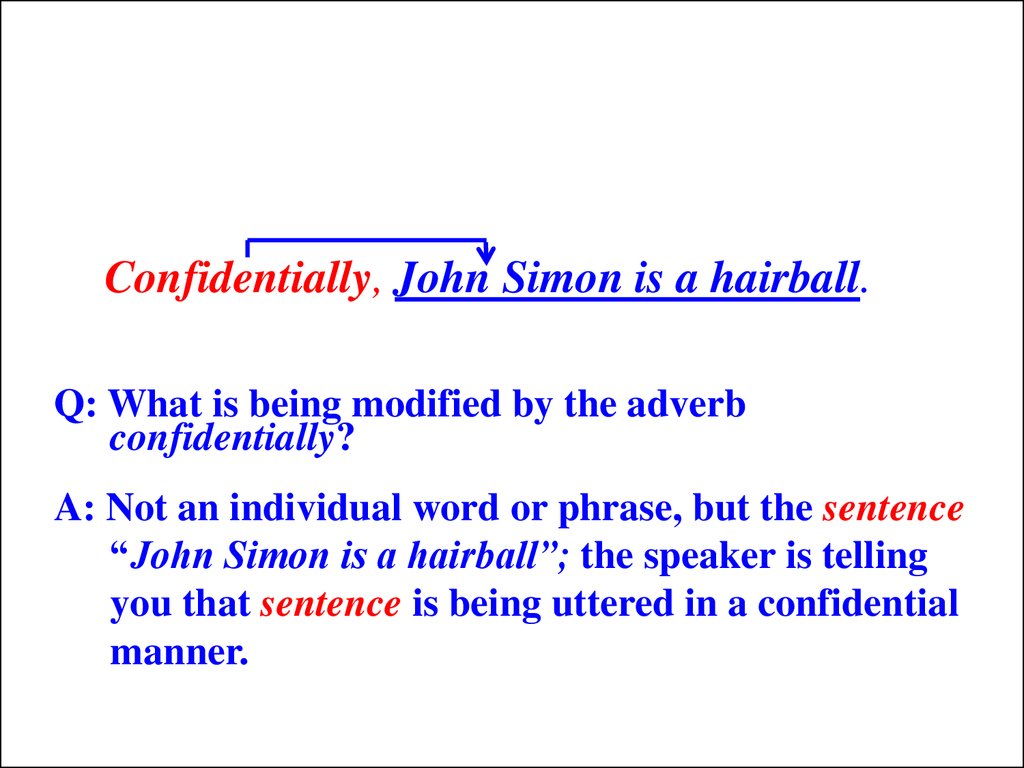

Confidentially, John Simon is a hairball.Q: What is being modified by the adverb

confidentially?

A: Not an individual word or phrase, but the sentence

“John Simon is a hairball”; the speaker is telling

you that sentence is being uttered in a confidential

manner.

28.

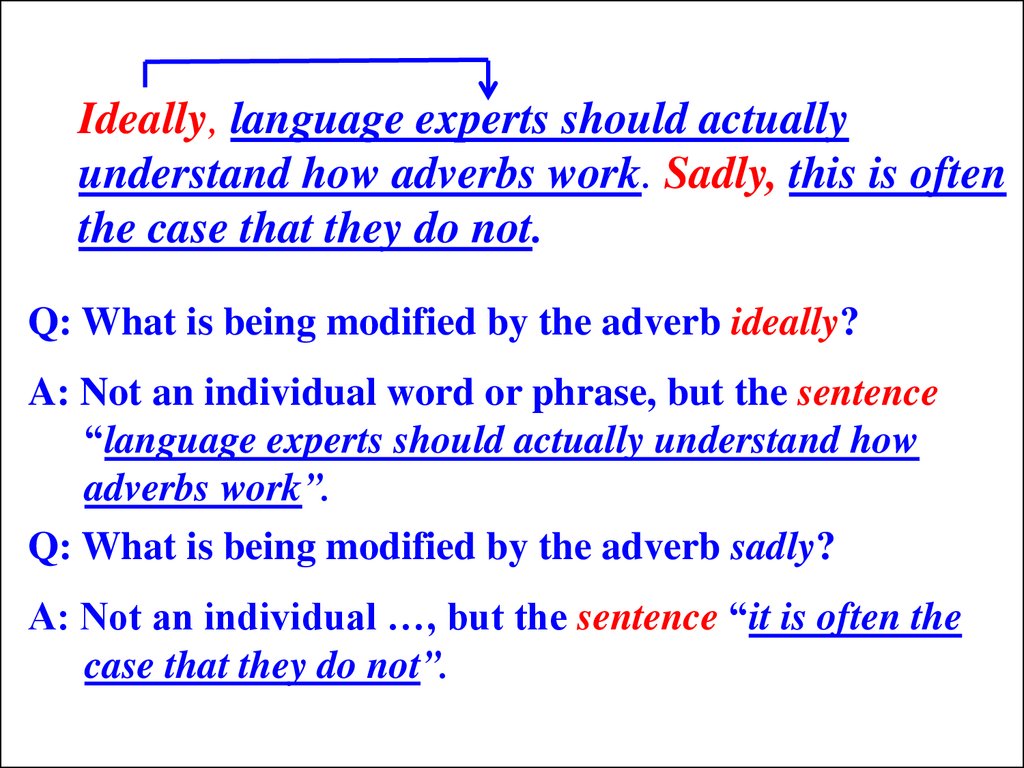

Ideally, language experts should actuallyunderstand how adverbs work. Sadly, this is often

the case that they do not.

Q: What is being modified by the adverb ideally?

A: Not an individual word or phrase, but the sentence

“language experts should actually understand how

adverbs work”.

Q: What is being modified by the adverb sadly?

A: Not an individual …, but the sentence “it is often the

case that they do not”.

29.

Is there anything wrong with any of thesesentences? [No]

Are they different in any way from hopefully?

[No]

Does the jughead who came up with this “rule”

know what he/she is talking about? [No]

Why was hopefully picked on and not candidly,

basically, incidentally, predictably, oddly,

supposedly …? [No one knows]

30.

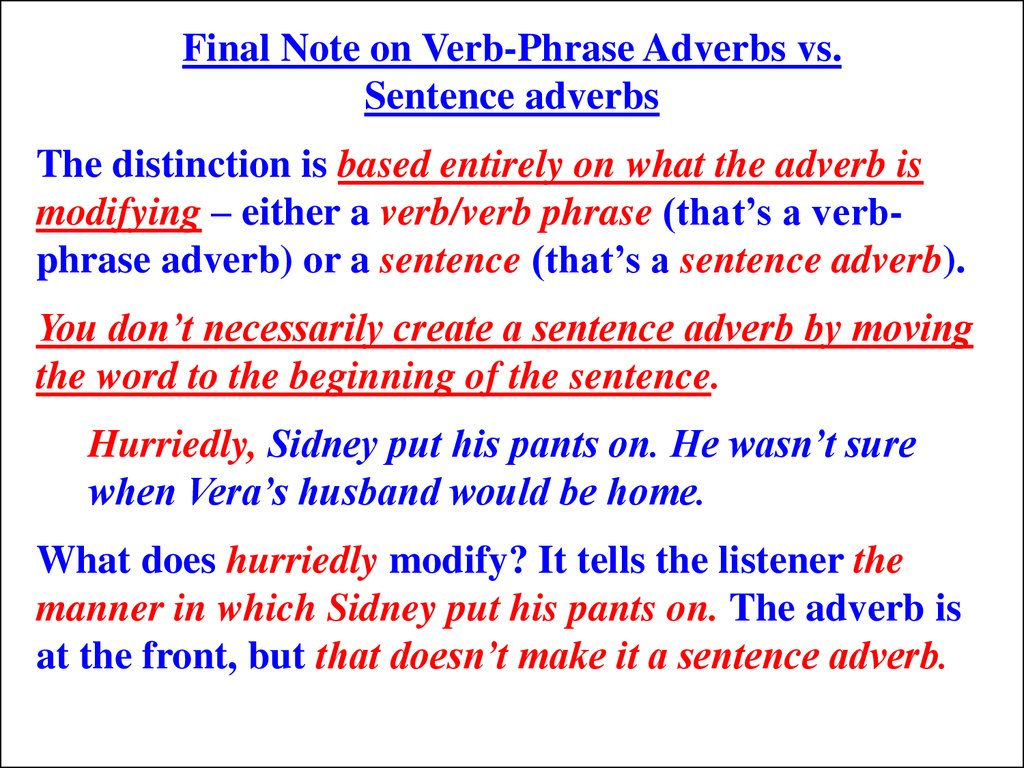

Final Note on Verb-Phrase Adverbs vs.Sentence adverbs

The distinction is based entirely on what the adverb is

modifying – either a verb/verb phrase (that’s a verbphrase adverb) or a sentence (that’s a sentence adverb).

You don’t necessarily create a sentence adverb by moving

the word to the beginning of the sentence.

Hurriedly, Sidney put his pants on. He wasn’t sure

when Vera’s husband would be home.

What does hurriedly modify? It tells the listener the

manner in which Sidney put his pants on. The adverb is

at the front, but that doesn’t make it a sentence adverb.

31.

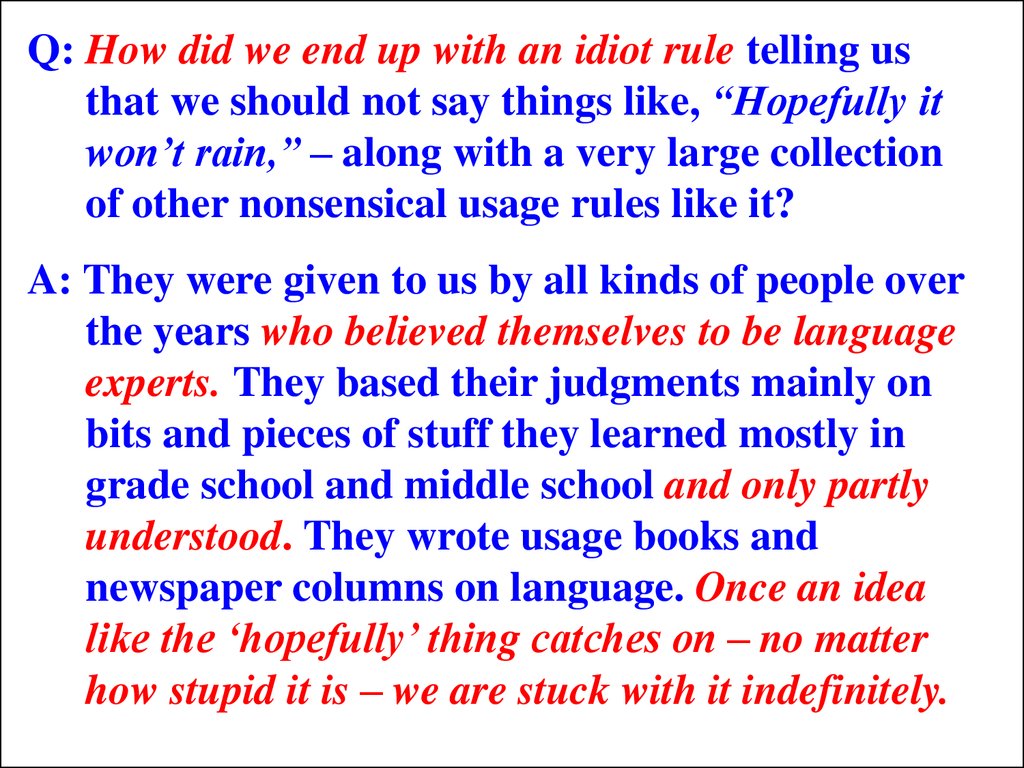

Q: How did we end up with an idiot rule telling usthat we should not say things like, “Hopefully it

won’t rain,” – along with a very large collection

of other nonsensical usage rules like it?

A: They were given to us by all kinds of people over

the years who believed themselves to be language

experts. They based their judgments mainly on

bits and pieces of stuff they learned mostly in

grade school and middle school and only partly

understood. They wrote usage books and

newspaper columns on language. Once an idea

like the ‘hopefully’ thing catches on – no matter

how stupid it is – we are stuck with it indefinitely.

32.

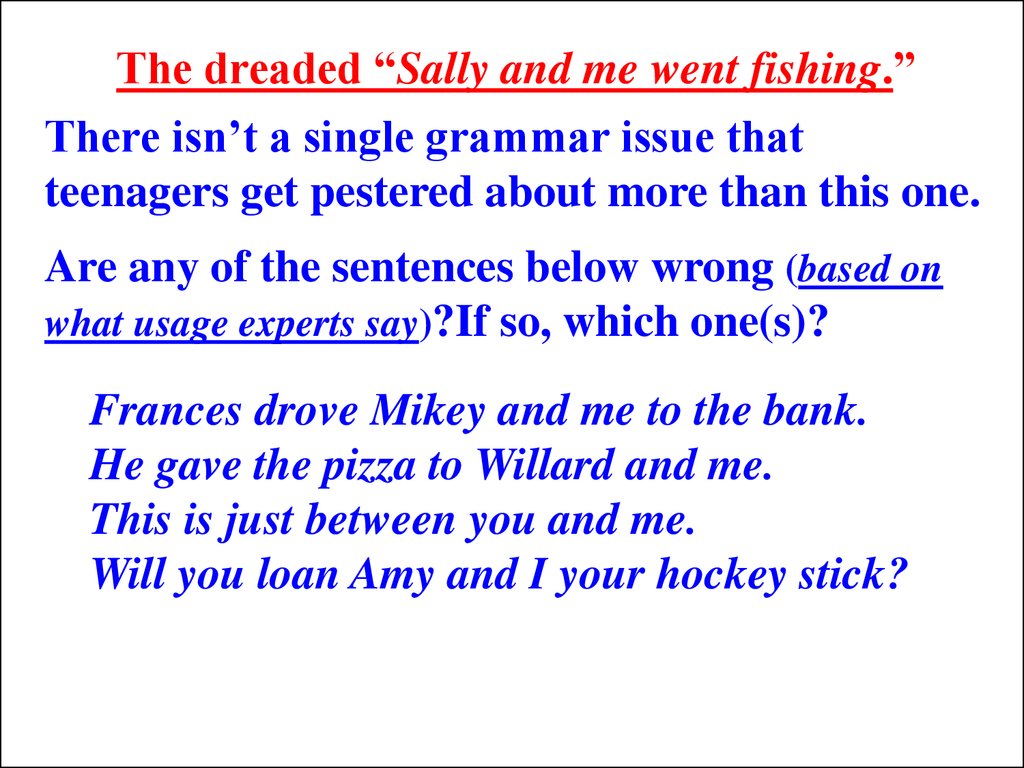

The dreaded “Sally and me went fishing.”There isn’t a single grammar issue that

teenagers get pestered about more than this one.

Are any of the sentences below wrong (based on

what usage experts say)?If so, which one(s)?

Frances drove Mikey and me to the bank.

He gave the pizza to Willard and me.

This is just between you and me.

Will you loan Amy and I your hockey stick?

33.

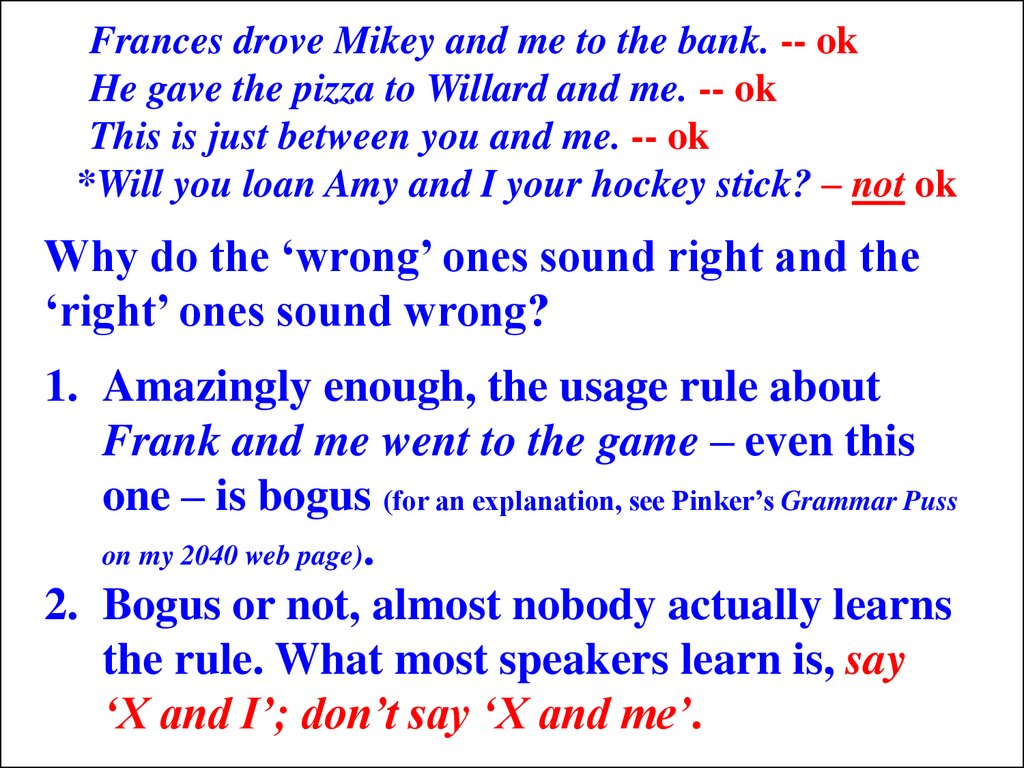

Frances drove Mikey and me to the bank. -- okHe gave the pizza to Willard and me. -- ok

This is just between you and me. -- ok

*Will you loan Amy and I your hockey stick? – not ok

Why do the ‘wrong’ ones sound right and the

‘right’ ones sound wrong?

1. Amazingly enough, the usage rule about

Frank and me went to the game – even this

one – is bogus (for an explanation, see Pinker’s Grammar Puss

on my 2040 web page).

2. Bogus or not, almost nobody actually learns

the rule. What most speakers learn is, say

‘X and I’; don’t say ‘X and me’.

34.

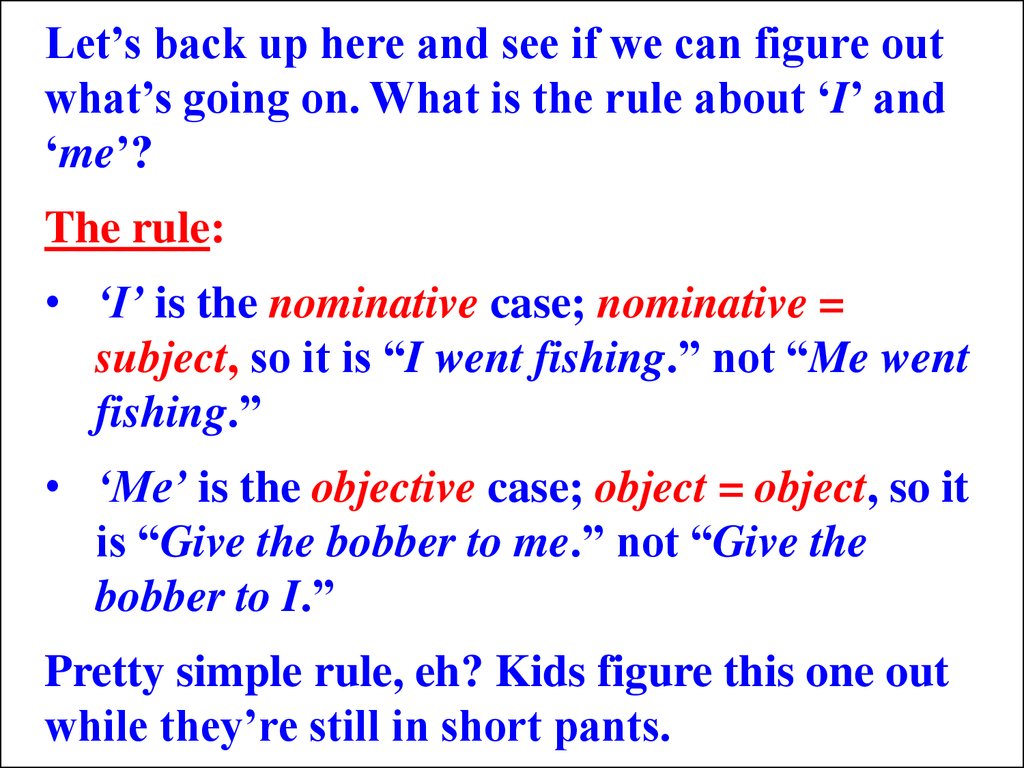

Let’s back up here and see if we can figure outwhat’s going on. What is the rule about ‘I’ and

‘me’?

The rule:

• ‘I’ is the nominative case; nominative =

subject, so it is “I went fishing.” not “Me went

fishing.”

• ‘Me’ is the objective case; object = object, so it

is “Give the bobber to me.” not “Give the

bobber to I.”

Pretty simple rule, eh? Kids figure this one out

while they’re still in short pants.

35.

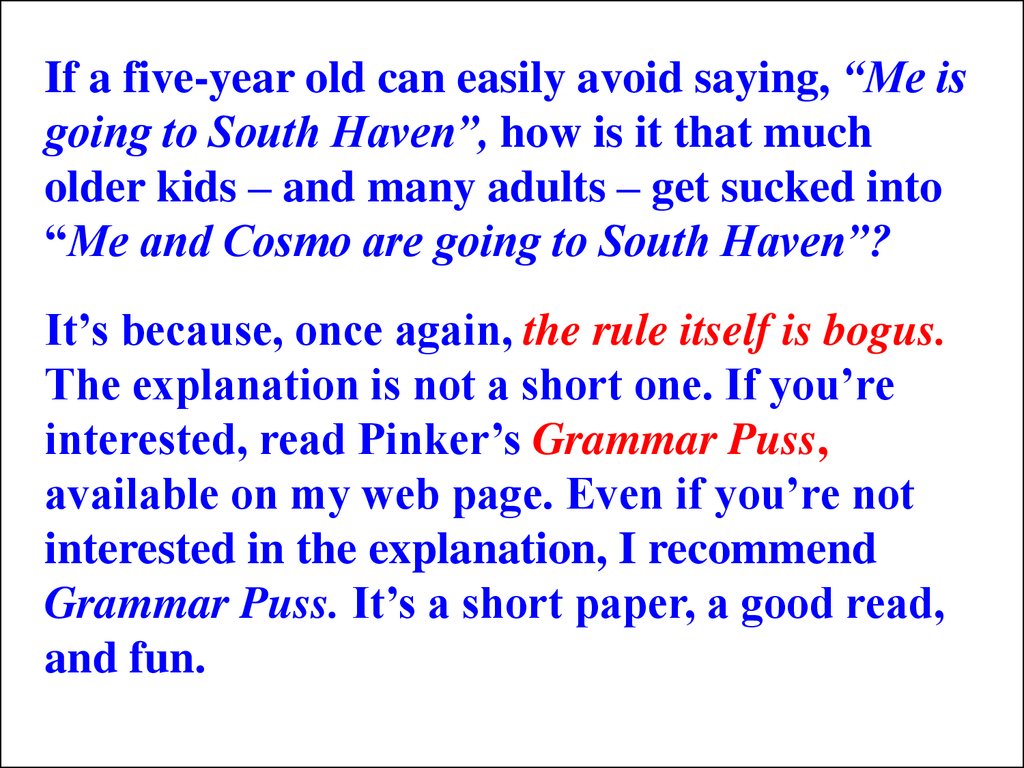

If a five-year old can easily avoid saying, “Me isgoing to South Haven”, how is it that much

older kids – and many adults – get sucked into

“Me and Cosmo are going to South Haven”?

It’s because, once again, the rule itself is bogus.

The explanation is not a short one. If you’re

interested, read Pinker’s Grammar Puss,

available on my web page. Even if you’re not

interested in the explanation, I recommend

Grammar Puss. It’s a short paper, a good read,

and fun.

36.

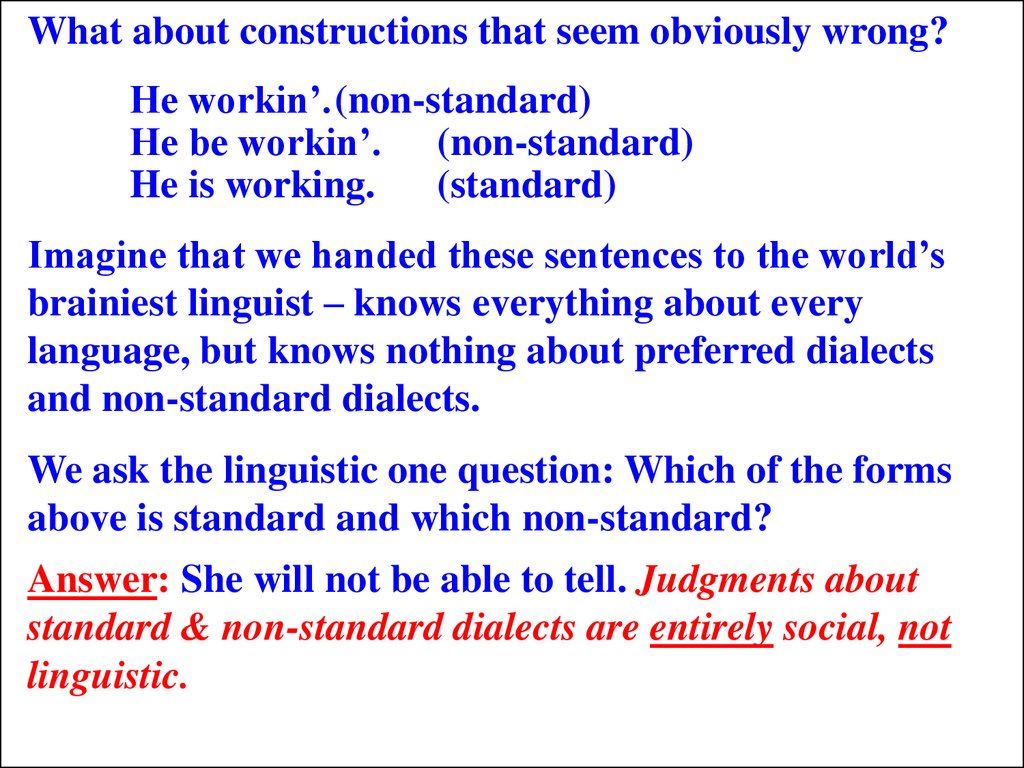

What about constructions that seem obviously wrong?He workin’.(non-standard)

He be workin’. (non-standard)

He is working.

(standard)

Imagine that we handed these sentences to the world’s

brainiest linguist – knows everything about every

language, but knows nothing about preferred dialects

and non-standard dialects.

We ask the linguistic one question: Which of the forms

above is standard and which non-standard?

Answer: She will not be able to tell. Judgments about

standard & non-standard dialects are entirely social, not

linguistic.

37.

One last point: Is it the case that non-standard forms arestripped-down, or simplified versions of the standard dialect?

No. There are grammatical features in the standard dialect that

can go unmarked in the non-standard dialect.

Just as often the reverse is true. BEV:

He workin’.

Not the same as “He is working.” Specifically means he’s

working right now.

He be workin’. Not the same as “He is working.” Refers specifically to a

habitual or frequent activity, as in: “"He be workin'

Tuesdays all month."

A form of aspect is being marked here that is ignored in SAE.

Does that make SAE impoverished? No, there are other ways to

do it, using words like right now or usually.

One more simple example: SAE “you” for both plural and

singular vs. the non-standard “y’all’ (south) or ‘youse’ (NY,

Philly, etc.)

38.

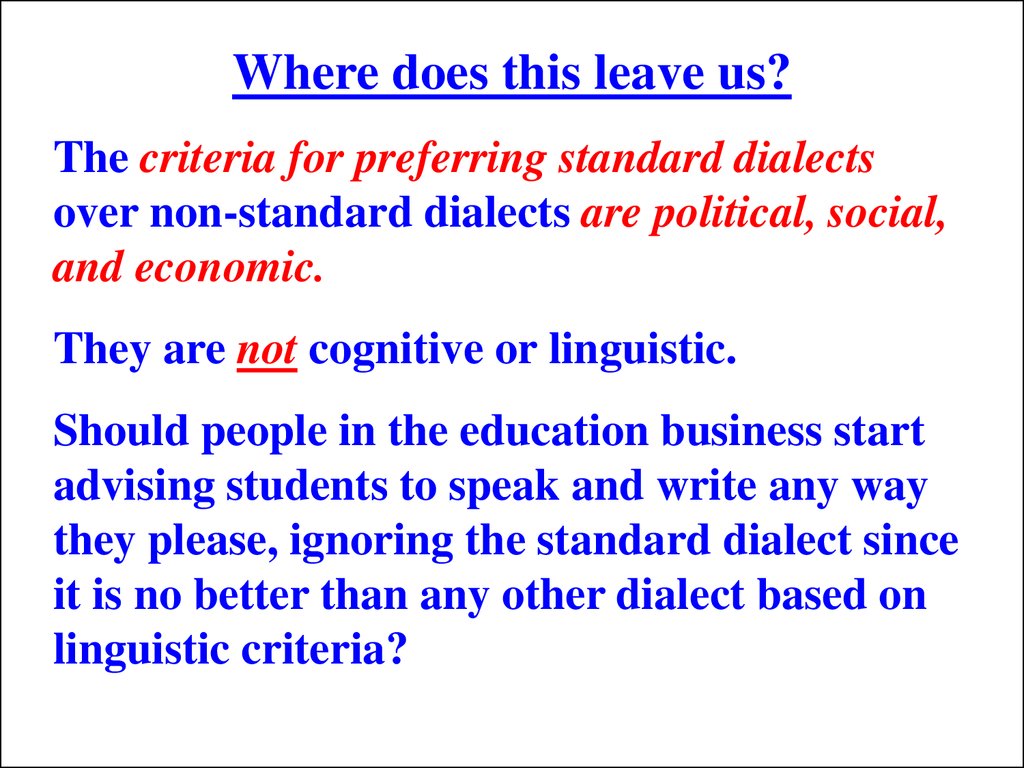

Where does this leave us?The criteria for preferring standard dialects

over non-standard dialects are political, social,

and economic.

They are not cognitive or linguistic.

Should people in the education business start

advising students to speak and write any way

they please, ignoring the standard dialect since

it is no better than any other dialect based on

linguistic criteria?

39.

The reality is that the ability to speak somethingclose to standard English (or a “cultured” form of

Southern or NYC speech) is a valuable skill. Imagine

you’re interviewing for a job.

Q: How did you find out about this position?

A: Well, I ain’t got no job, so I was looking at the want

ads and that’s where I seen it.

Even if you’re applying for a job running a cash

register or waiting on tables, you’re probably

cooked right there. Humans make judgments about

people based on their speech patterns. That’s here to

stay.

40.

So, what should educators do? It should not be adifficult problem. Unlike the U.S., multilingualism is

extremely common throughout the world. (Swiss kids: no

difficulty learning German, French & English; children in Chad:

no trouble learning Arabic and French; The Netherlands: in the

larger cities almost everyone speaks (at least) Dutch and English.)

What’s the point? There’s no reason that kids should

have any trouble learning standard English in

addition to their native dialect.

But: There is also no reason for teachers to get it in

their heads (or convey to their students) that the nonstandard dialects spoken by many kids represent bad

English. It isn’t bad English.

41.

[Read this on your own.]Attitude changes about “proper” and “improper dialects” do

not come easily, but they do sometimes happen. Check out this

commentary on Cockney.

Changing attitudes towards Cockney English. The Cockney accent has long been looked down

upon and thought of as inferior by many. In 1909 these attitudes even received an official

recognition thanks to the report of The Conference on the Teaching of English in London

Elementary Schools issued by the London County Council, where it is stated that "[…] the

Cockney mode of speech, with its unpleasant twang, is a modern corruption without legitimate

credentials, and is unworthy of being the speech of any person in the capital city of the Empire".

On the other hand, however, there started rising at the same time cries in defence of Cockney as,

for example the following one: "The London dialect is really, especially on the South side of the

Thames, a perfectly legitimate and responsible child of the old kentish tongue […] the dialect of

London North of the Thames has been shown to be one of the many varieties of the Midland or

Mercian dialect, flavoured by the East Anglian variety of the same speech […]". Since then, the

Cockney accent has been more accepted as an alternative form of the English Language rather

than an "inferior" one; in the 1950s the only accent to be heard on the BBC (except in

entertainment programmes such as Sooty) was RP, whereas nowadays many different accents,

including Cockney or ones heavily influenced by it, can be heard on the BBC. In a survey of

2000 people conducted by Coolbrands in autumn 2008, Cockney was voted equal fourth coolest

accent in Britain with 7% of the votes, while The Queen's English was considered the coolest,

with 20% of the votes. Brummie was voted least popular, receiving just 2%. [Source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cockney]

Английский язык

Английский язык