Похожие презентации:

Public Economics

1. Public Economics

Sergei Izmalkov"Where I am notwith

understood,

it shall be

assistance of

concluded that something very useful and

Alexander

Tonis

profound is couched underneath." J. Swift.

Based on slides by Aaron S. Yelowitz - Copyright 2005 © Worth Publishers prepared for J. Gruber “Public Finance and Public Policy.”

2. Requirements

4+ homeworksProject

Final exam

Distribution: 40-20-40

read before class

no cheating

3. Textbooks

J. Gruber "Public Finance and Public Policy,"Worth Publishers, 2007 or later editions

Russian translation also exists

Аткинсон, Энтони Б., Стиглиц, Джозеф Э.

(1995) "Лекции по экономической теории

государственного сектора", Изд. Аспект

Пресс, 1995.

4. Topics

1. Subject and methods of Public Finance.2. Externalities. Applications to Environment

and Health.

3. Public Goods. Optimal, private, and public

provision.

4. Political economy. Voting. Privatization.

Corruption.

5. Education. The role of government.

Competition. Returns to education.

5. Topics (cont)

6. Social Insurance. Adverse selection andmoral hazard.

7. Social security. Unemployment insurance.

8. Health Insurance. Public vs. Private. Health

Care Reforms.

9. Income Distribution and Welfare programs.

10. Overview of taxation topics.

11. Local public goods. Tiebout model.

12. Fiscal federalism.

6. Introduction What is the proper role of government?

Expenditure side: What services should thegovernment provide?

Taxation side: How should the government raise its

money?

7. THE FOUR QUESTIONS OF PUBLIC FINANCE

When should the government intervene in theeconomy?

How might the government intervene?

What is the effect of those interventions on

economic outcomes?

Why do governments choose to intervene in the

way that they do?

8. When Should the Government Intervene in the Economy?

Normally, private markets are competitive andefficient.

Generally hard to justify government intervention in

markets. But two main justifications are:

Market failures

Redistribution

“Abnormal” situations: crises, disasters.

9. When Should the Government Intervene? Market failures

“Problems” for markets:Externalities

Private (Asymmetric) Information

Small number of agents on one or both sides of the

market / market (monopoly) power

In the context of health insurance, some people are

uninsured…

10. When Should the Government Intervene? Market failures

In 2003, there were 45 million people withouthealth insurance in the United States, or 15.6% of

the population.

Does it imply that the market does not work?

Lack of insurance could cause negative

externalities from contagious disease–the

uninsured may not take account of their impact on

others.

11. When Should the Government Intervene? Market failures

Measles epidemic from 1989-1991, caused by lowimmunization rates for disadvantaged youth, was the

problem.

In 1960s: 3-4 m. cases, 500 deaths per year

In 1963 vaccine introduced; by 1980 less than 3000 cases per

year

1989-1991 a huge resurgence occurred: over 50000 cases and

123 deaths.

What happened?

Solution: Propaganda plus subsidy for vaccines for low-income

families.

Did it work?

Immunization rates increased from 70% to 90% in 1995: less

then 300 confirmed cases.

12. When Should the Government Intervene? Redistribution

Government may care about both the size of the“economic pie” as well as the size of each person’s

slice of that pie.

For example, society may value an additional $1 of

consumption by a poor person more highly than $1

of consumption by a rich person.

Redistribution is the shifting of resources from

some groups in society to others.

Other reasons?

13. When Should the Government Intervene? Redistribution

Of the uninsured, for example, roughly three-quarters are in families with incomes below the

median income level in the United States.

Society may feel that it is appropriate to redistribute

from those with insurance (who tend to have higher

incomes) to those without insurance (who tend to

have lower incomes).

Redistribution often involves efficiency losses.

The act of redistribution can change a person’s

behavior. Taxing the rich to distribute money to the

poor could cause both groups to work less hard.

14. How Might the Government Intervene?

If the government wants to intervene in a market, there are anumber of options:

Using the price mechanism with taxes or subsidies.

Tax credits that lower the “effective price” of health

insurance.

Mandate that either individuals or firms provide the good.

“Pay-or-play” mandates that require employers to provide

health insurance, such as California’s Health Insurance Act.

Public Provision

The Medicare program for U.S. senior citizens.

Public Financing of Private Provision

Medicare prescription drug cards, where private companies

administer the drug insurance.

15. What Are the Effects of Alternative Interventions?

Much of the focus of empirical public finance isassessing the “direct” and “indirect” effects of

government actions.

Direct effects of government actions assume “no

behavioral responses” and examine the intended

consequences of those actions.

Indirect effects arise because some people change

their behavior in response to an intervention. This

is sometimes called the “law of unintended

consequences.”

16. What Are the Effects of Alternative Interventions? Expanding health insurance

Direct effect of government provision of health insurance for theuninsured: Roughly 44 million Americans could be covered at cost

of $88 billion. This would be the intent of the law.

Indirect effect of such a policy: Some “crowd-out” of other

sources of health insurance for the “free” government health

insurance.

Potentially large, because nearly 200 million Americans had

private insurance in 2003.

If 90 million people dropped private insurance, this would

triple the cost to $268 billion.

If only 10% of people (20 million) dropped insurance, the

costs would rise to only $124 billion.

Key question: How many of these people would respond? The

theory does not provide guidance on magnitudes.

17. The Congressional Budget Office

Congressional Budget Office (CBO) providesnonpartisan analyses needed for economic decisions

of the government.

Plays role as “scorekeeper” by estimating costs.

Played a role in the defeat of the Clinton 1994

health care plan because of its estimate of the cost.

18. Why Do Governments Do What They Do?

Governments do not simply behave as benignactors who intervene only because of market failure

and redistribution.

Tools of political economy helps us understand

how governments make public policy decisions.

Just as market failures can lead to market

inefficiency, there are a host of government failures that

lead to inappropriate government intervention.

19. Why Do Governments Do What They Do?

For example, substantial variation across developedcountries in health care delivery suggests efficiency

and redistribution are not the only considerations.

U.S.: Private health insurance

Canada: National public health insurance

Germany: Mandates private health coverage

U.K.: Free national health care

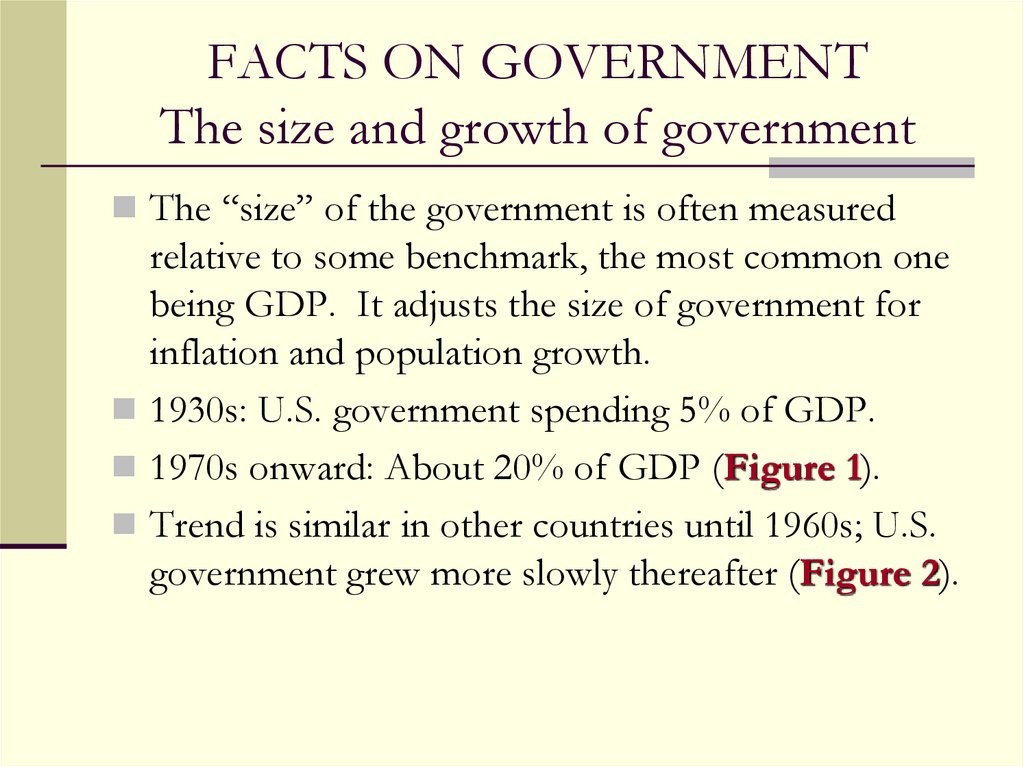

20. FACTS ON GOVERNMENT The size and growth of government

The “size” of the government is often measuredrelative to some benchmark, the most common one

being GDP. It adjusts the size of government for

inflation and population growth.

1930s: U.S. government spending 5% of GDP.

1970s onward: About 20% of GDP (Figure 1).

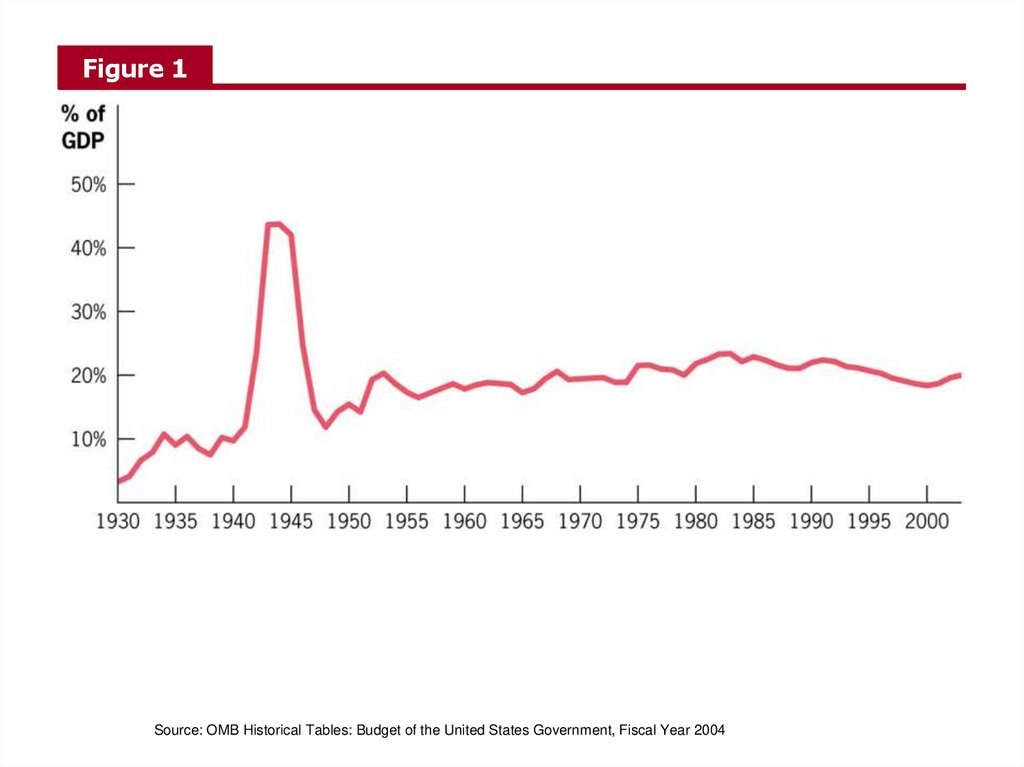

Trend is similar in other countries until 1960s; U.S.

government grew more slowly thereafter (Figure 2).

21.

Figure 1Source: OMB Historical Tables: Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2004

22.

Figure 2Source: OECD Historical Statistics

23. FACTS ON GOVERNMENT Decentralization and budgeting

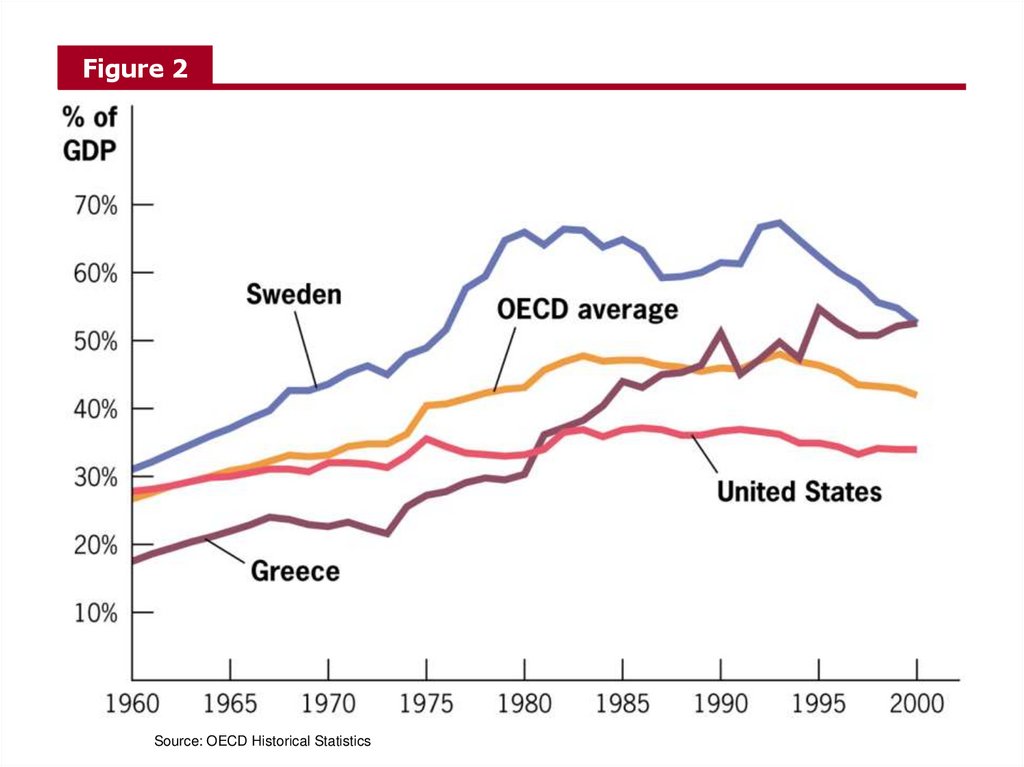

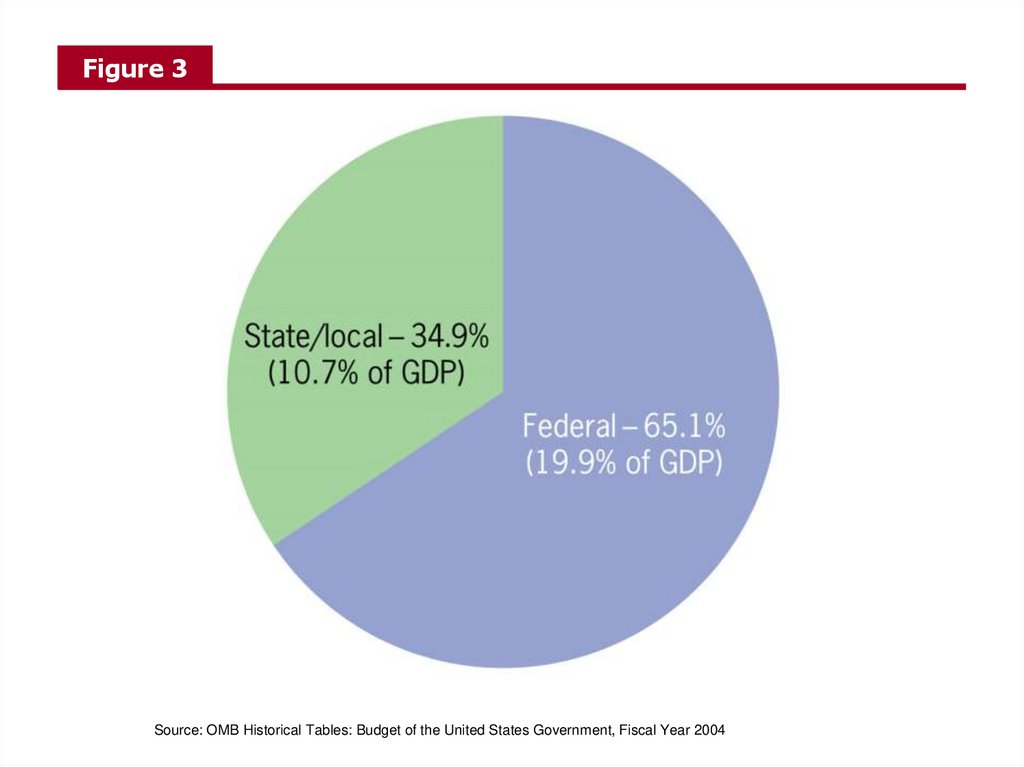

Other featuresDecentralization: In the United States., local, state

and federal governments all spend substantial

amounts of money (Figure 3).

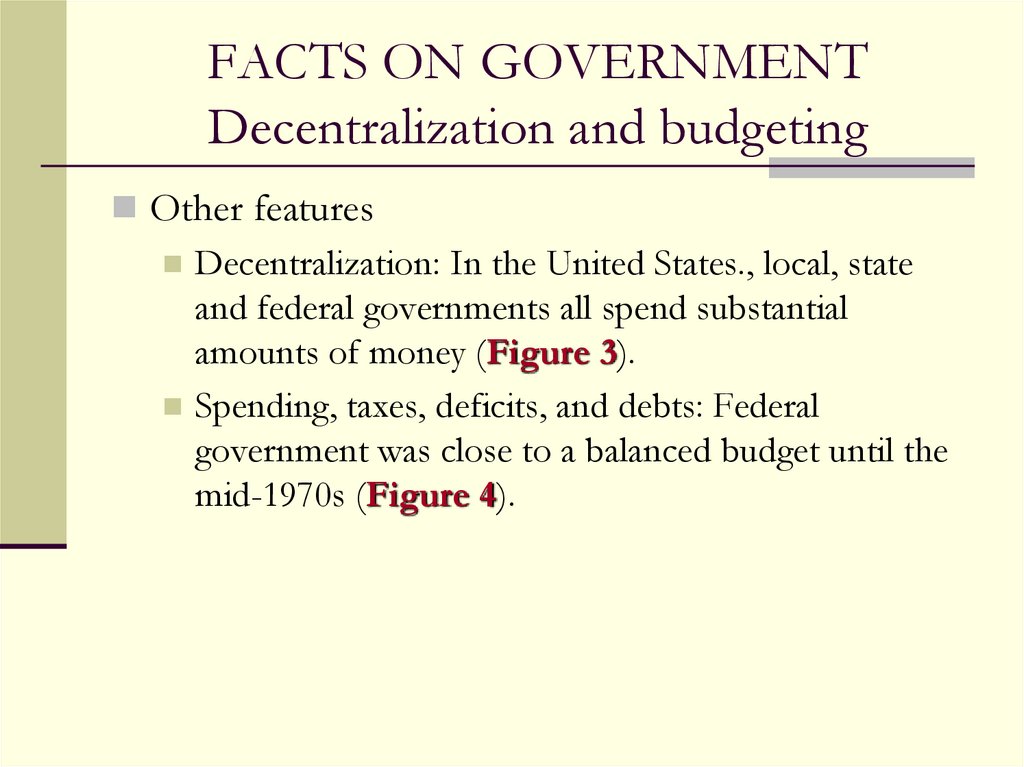

Spending, taxes, deficits, and debts: Federal

government was close to a balanced budget until the

mid-1970s (Figure 4).

24.

Figure 3Source: OMB Historical Tables: Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2004

25.

Figure 4Source: OMB Historical Tables: Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2004

26. FACTS ON GOVERNMENT Distribution of spending

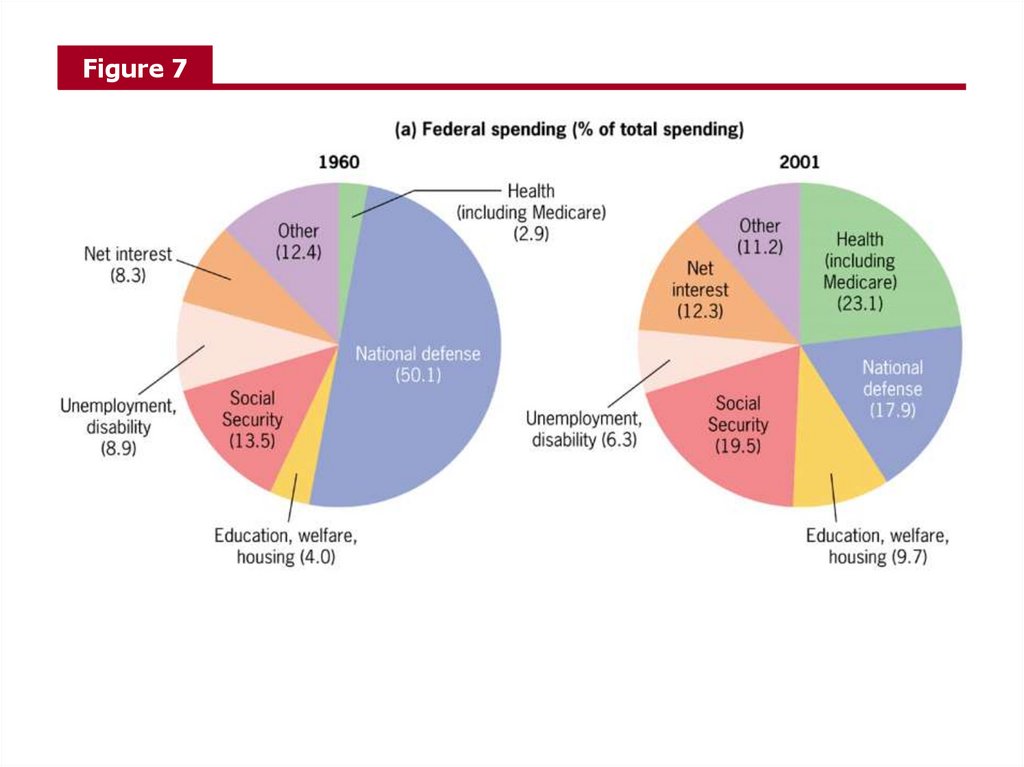

Other featuresDistribution of spending (Figure 7).

In 1960: over half of federal government spending on

defense (a classic “public good”).

In 2001: Less than 20% of budget for defense, much

more devoted to social insurance programs.

Distribution in state and local spending has not changed

as dramatically; education makes up the single largest

component of spending.

27.

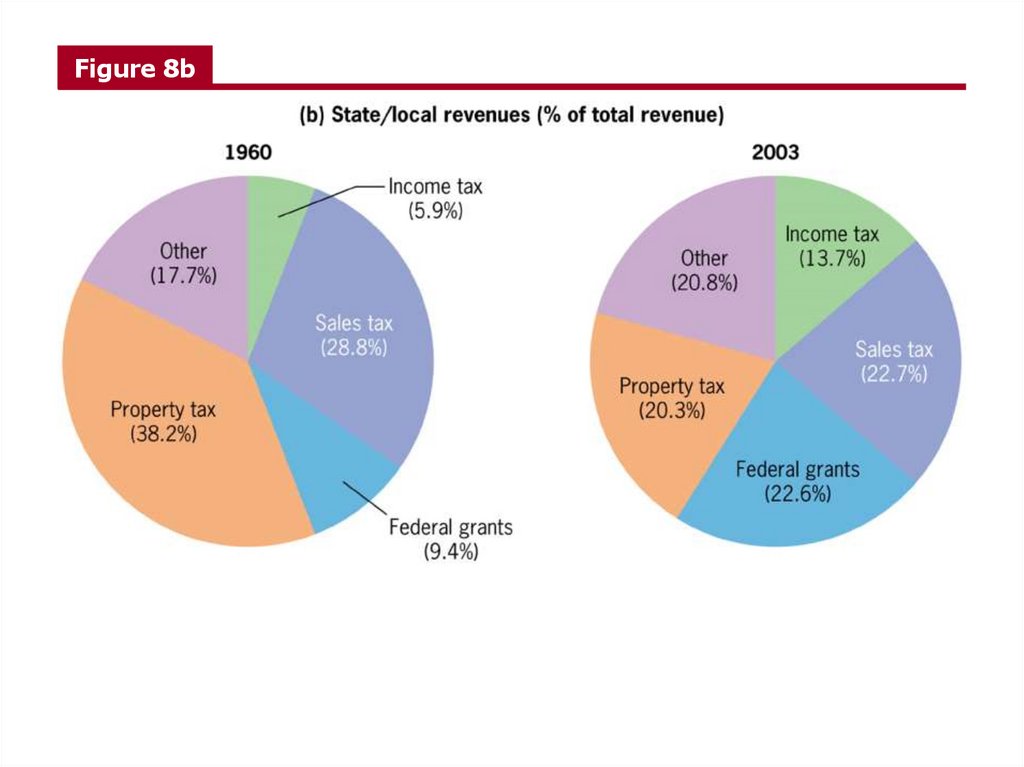

Figure 728. FACTS ON GOVERNMENT Distribution of revenue sources

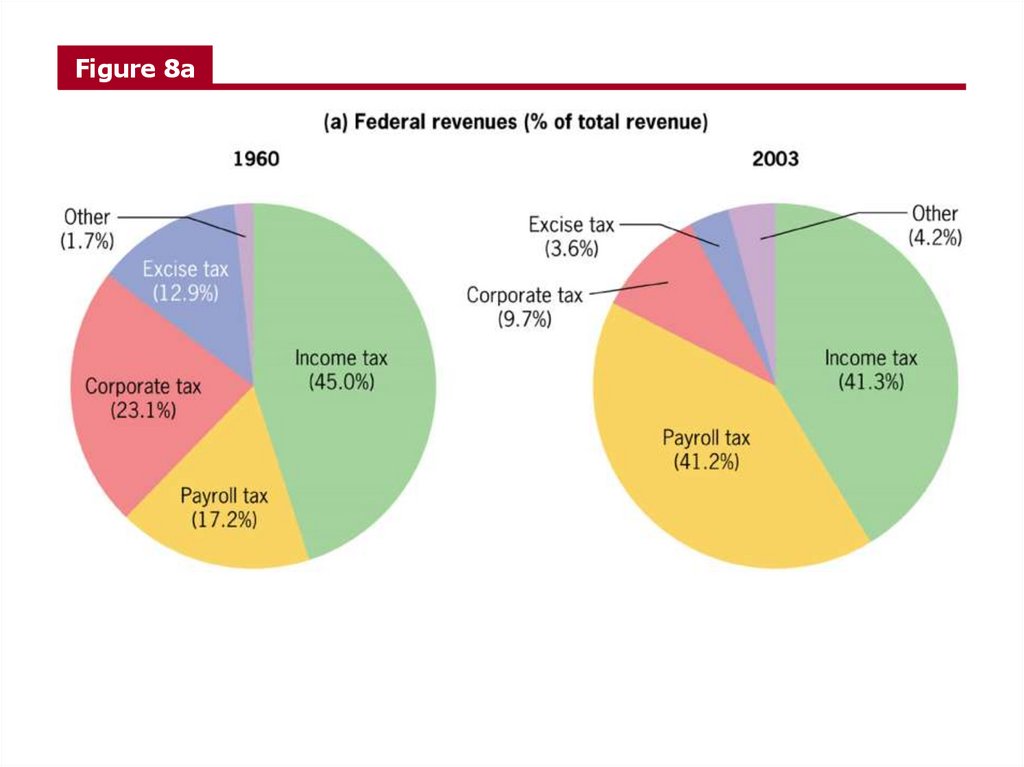

Other featuresDistribution of revenue (Figure 8a and 8b).

The individual income tax provides somewhat less than

half of federal revenue and has remained roughly

constant over time.

Big decline in revenue from corporate income tax, now less

than 10% of federal tax revenue.

Reduction in excise taxes.

Large growth in payroll taxes; now one-third of revenue.

29. FACTS ON GOVERNMENT Distribution of revenue sources

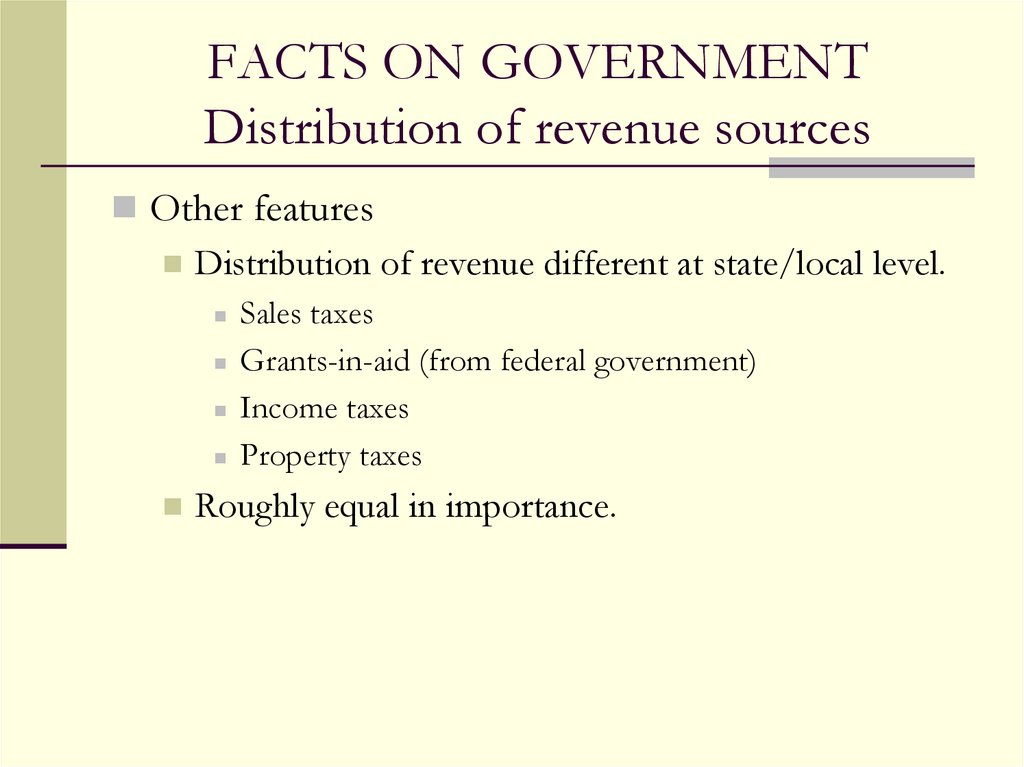

Other featuresDistribution of revenue different at state/local level.

Sales taxes

Grants-in-aid (from federal government)

Income taxes

Property taxes

Roughly equal in importance.

30.

Figure 8a31.

Figure 8b32. FACTS ON GOVERNMENT Regulatory role of the government

Other featuresRegulatory role–does not usually show up as a

government “cost” but does increase the reach of

government.

FDA regulates nearly 25% of consumer

expenditures.

OSHA regulates workplace safety at 7 million job

sites.

FCC, EPA.

33. Recap

Four key questions in public financeWhen should the government intervene in the economy?

How might the government intervene?

What is the effect of those interventions on economic

outcomes?

Why do governments choose to intervene in the way that they

do?

How should the government intervene?

What is the optimal size of the government?

34. Theoretical tools (recap):

Income and substitution effects. Equivalent andcompensating variations. Consumer surplus.

What are the social objectives?

Asymmetric information modeling: adverse

selection and moral hazard.

Mechanism design: auctions/procurement/voting

schemes/optimal taxation.

Dynamic optimization.

35.

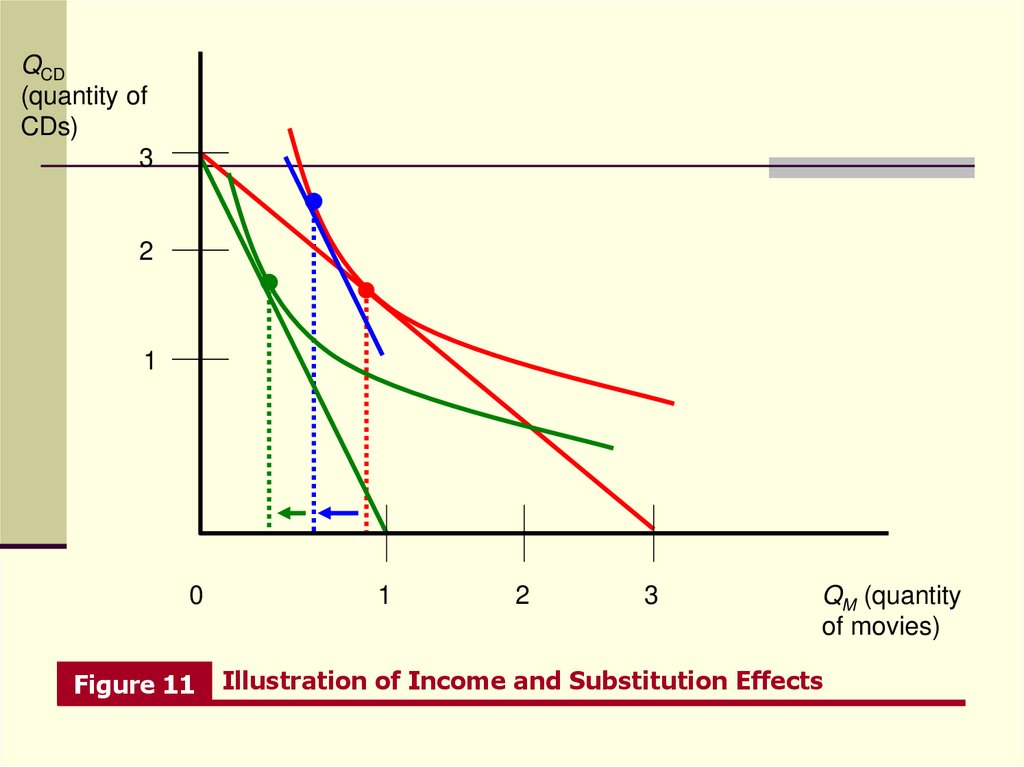

QCD(quantity of

CDs)

3

2

1

0

Figure 11

1

2

3

QM (quantity

of movies)

Illustration of Income and Substitution Effects

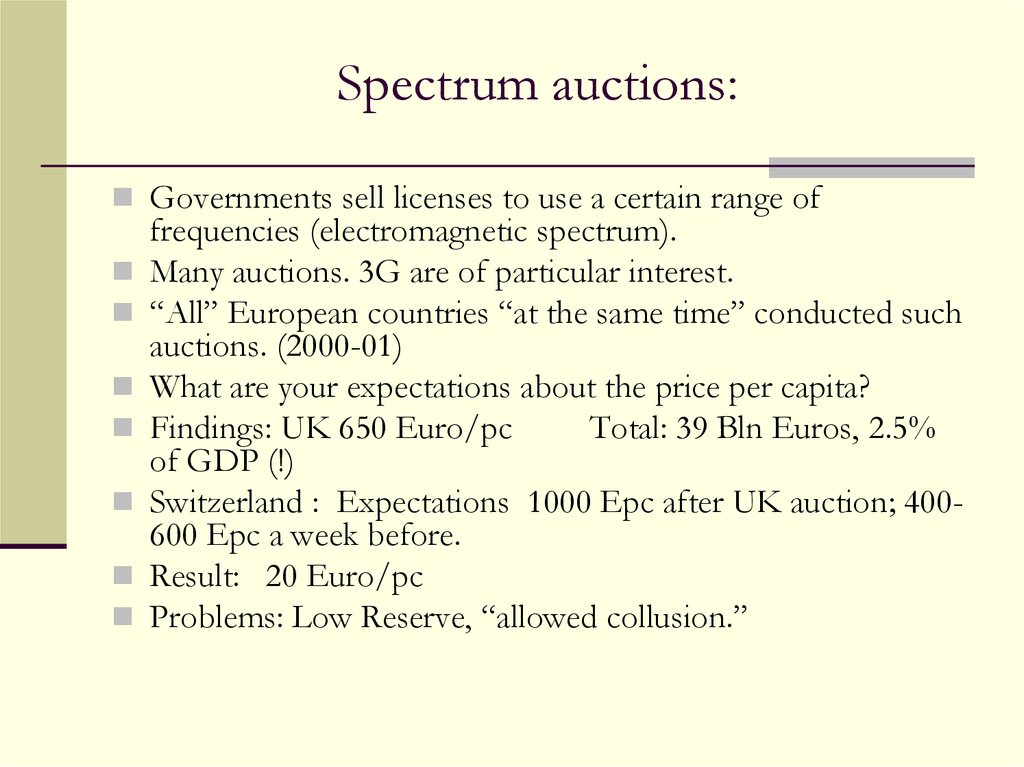

36. Spectrum auctions:

Governments sell licenses to use a certain range offrequencies (electromagnetic spectrum).

Many auctions. 3G are of particular interest.

“All” European countries “at the same time’’ conducted such

auctions. (2000-01)

What are your expectations about the price per capita?

Findings: UK 650 Euro/pc

Total: 39 Bln Euros, 2.5%

of GDP (!)

Switzerland : Expectations 1000 Epc after UK auction; 400600 Epc a week before.

Result: 20 Euro/pc

Problems: Low Reserve, “allowed collusion.”

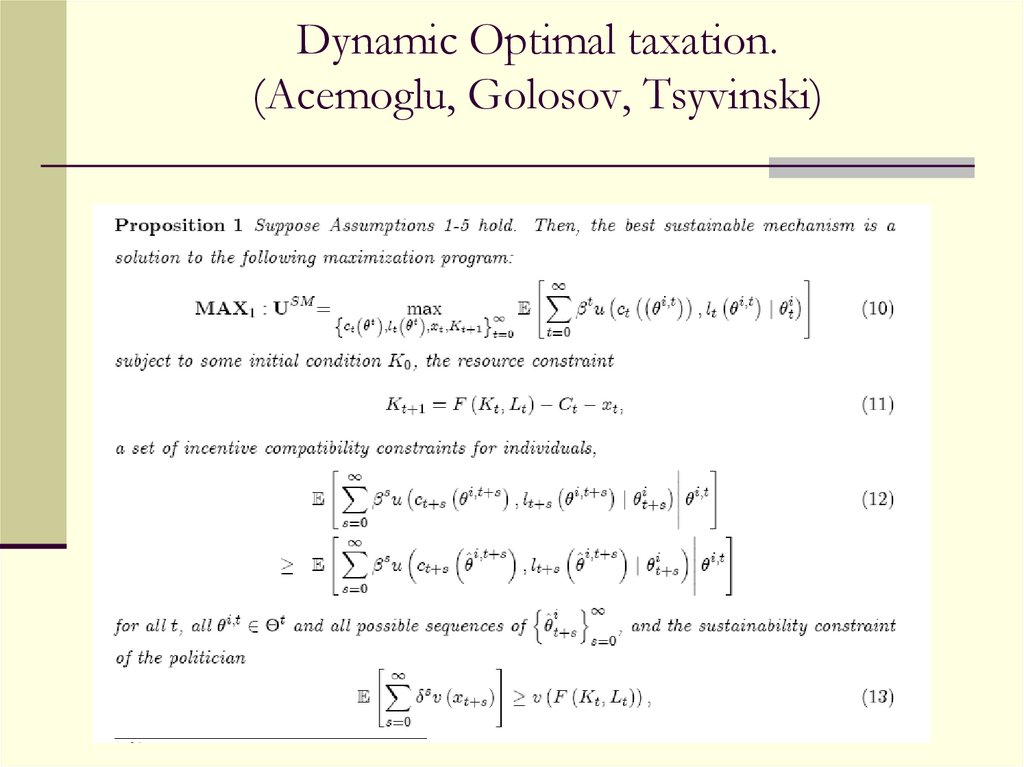

37. Dynamic Optimal taxation. (Acemoglu, Golosov, Tsyvinski)

38. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK TANF and labor supply among single mothers

TANF is “Temporary Assistance for NeedyFamilies.”

Cash welfare for poor families, mainly single

mothers.

For example, in New Mexico, family of three

receives $389 per month.

Assume the two “goods” in utility maximization

problem are leisure and food consumption.

Whatever time is not devoted to leisure is spent

working and earning money.

39. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK Identifying the budget constraint

What does the budget constraint look like?Assume the person can work up to 2000 hours per

year, at a wage rate of $10 per hour, and that TANF

is not yet in place.

Price of food is $1 per unit.

40. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK Identifying the budget constraint

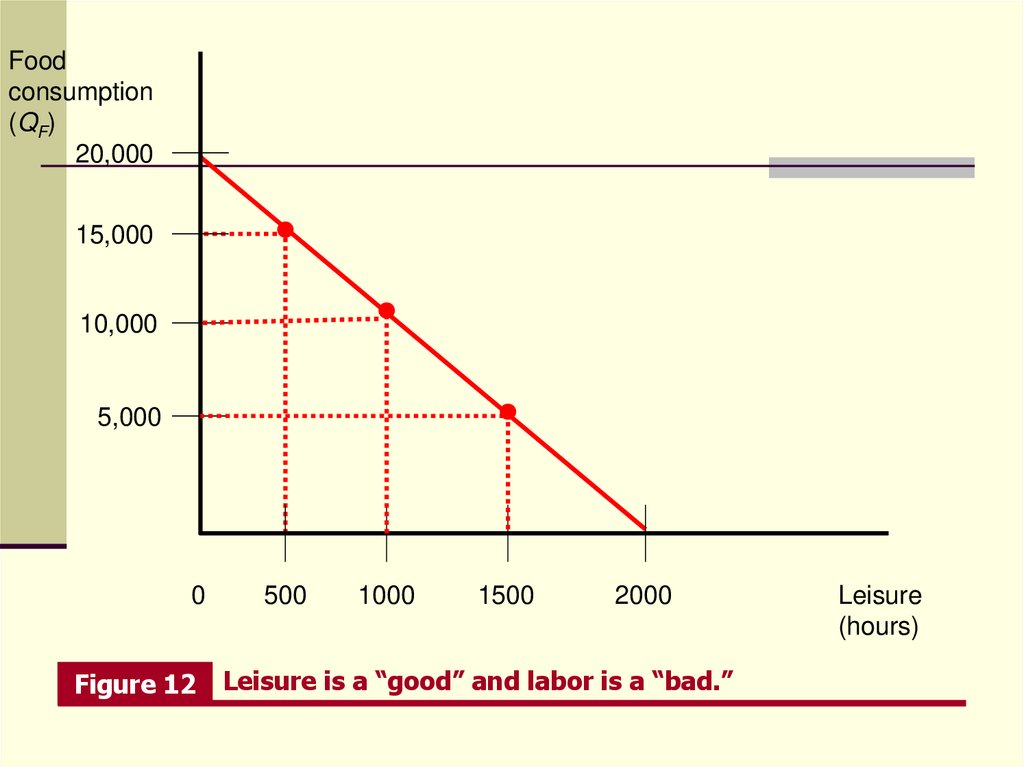

The “price” of one hour of leisure is the hourlywage rate.

Creates a direct tradeoff between leisure and food:

each hour of work brings her 10 units of food.

Figure 12 illustrates this.

41.

Foodconsumption

(QF)

20,000

15,000

10,000

5,000

0

Figure 12

500

1000

1500

2000

Leisure is a “good” and labor is a “bad.”

Leisure

(hours)

42. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK The effect of TANF on the budget constraint

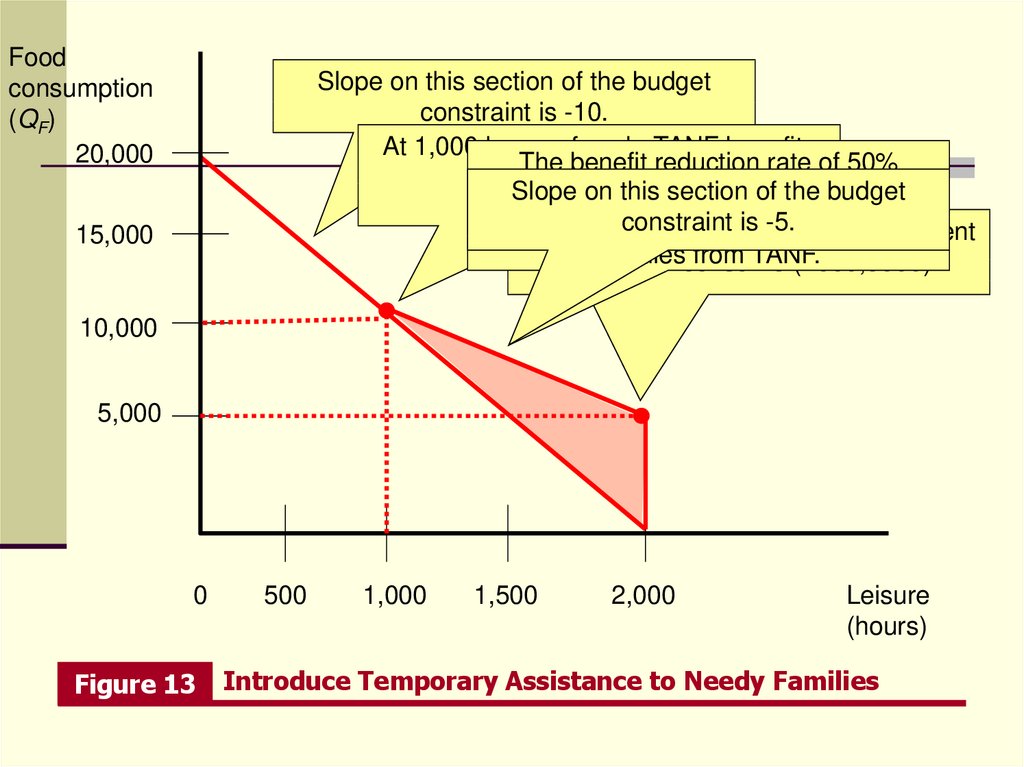

Now, let’s introduce TANF into the framework.TANF has two key features:

Benefit guarantee, G – amount that a recipient with

$0 earnings gets.

Benefit reduction rate, J – rate at which benefit

guarantee falls as earnings increases.

43. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK The effect of TANF on the budget constraint

Assume that benefit guarantee, G, is $5,000 per year.Assume the benefit reduction rate, J, is 50%.

Figure 13 illustrates this.

44.

Foodconsumption

(QF)

20,000

Slope on this section of the budget

constraint is -10.

At 1,000 hours of work, TANF benefits

The benefit reduction rate of 50%

fall to zero.

Slope onthe

thisguarantee

section ofas

theearnings

budget

reduces

constraint

isrepresents

-5. that a new

increase.

Green

area

$5000 guarantee

means

recipient

bundles

from TANF.

could

now consume

(2000,5000).

15,000

10,000

5,000

0

Figure 13

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

Leisure

(hours)

Introduce Temporary Assistance to Needy Families

45. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK The effect of changes in the benefit guarantee

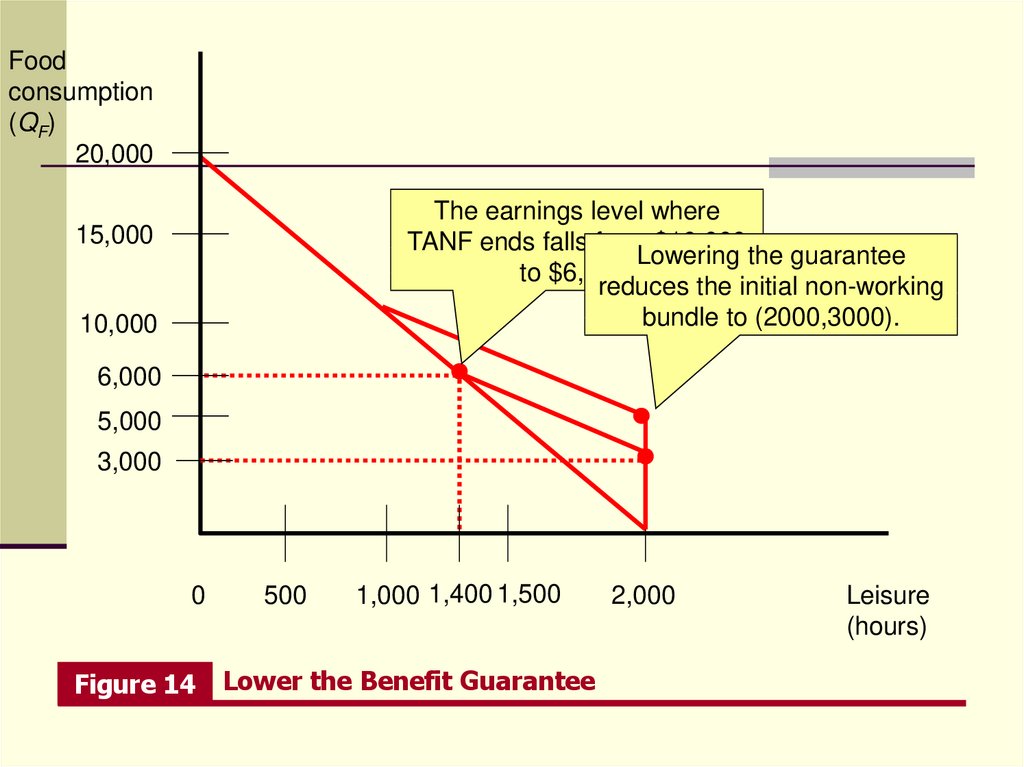

One possible “policy experiment” is reducing thebenefit guarantee level G.

What happens when G falls from $5,000 to $3,000,

holding all other parameters constant?

Figure 14 illustrates this.

46.

Foodconsumption

(QF)

20,000

The earnings level where

TANF ends falls from $10,000

Lowering the guarantee

to $6,000.

reduces the initial non-working

bundle to (2000,3000).

15,000

10,000

6,000

5,000

3,000

0

Figure 14

500

1,000 1,400 1,500

Lower the Benefit Guarantee

2,000

Leisure

(hours)

47. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK How large will the labor supply response be?

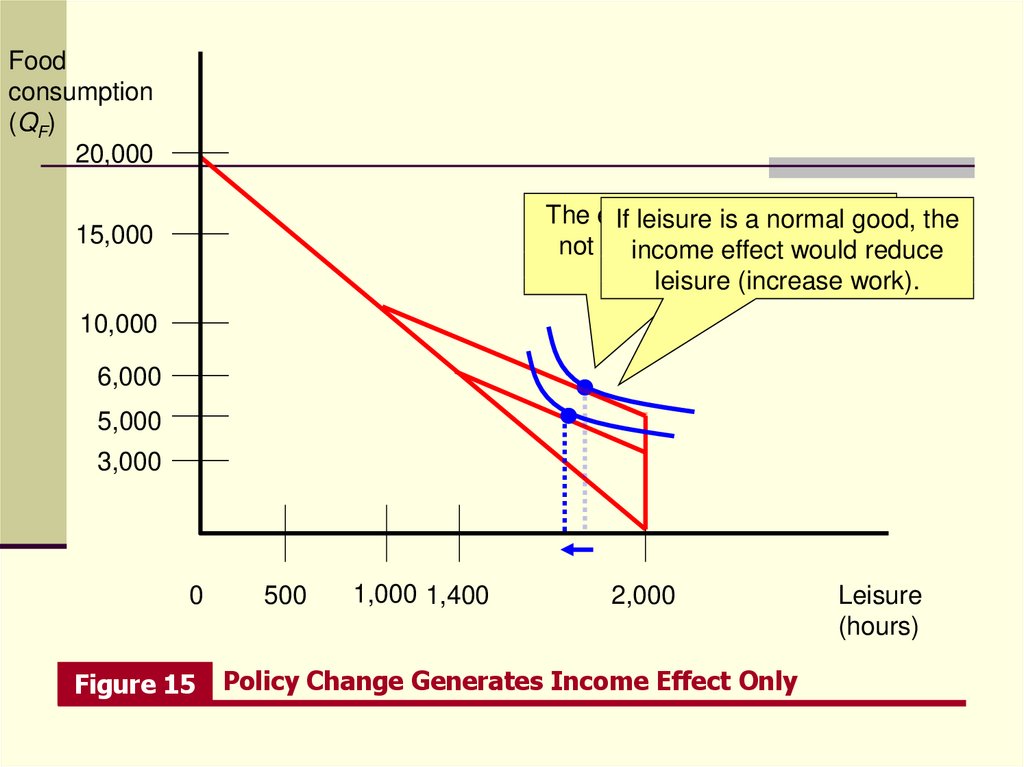

What is the expected labor supply response to sucha policy change?

It depends on where the single mother initially was

on the budget constraint.

If she initially earned less than $6,000 per year, the

policy change involves only an income effect, not a

substitution effect.

Figure 15 illustrates this.

48.

Foodconsumption

(QF)

20,000

The effective

rate does

If leisurewage

is a normal

good, the

not change

foreffect

this person.

income

would reduce

leisure (increase work).

15,000

10,000

6,000

5,000

3,000

0

Figure 15

500

1,000 1,400

2,000

Policy Change Generates Income Effect Only

Leisure

(hours)

49. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK How large will the labor supply response be?

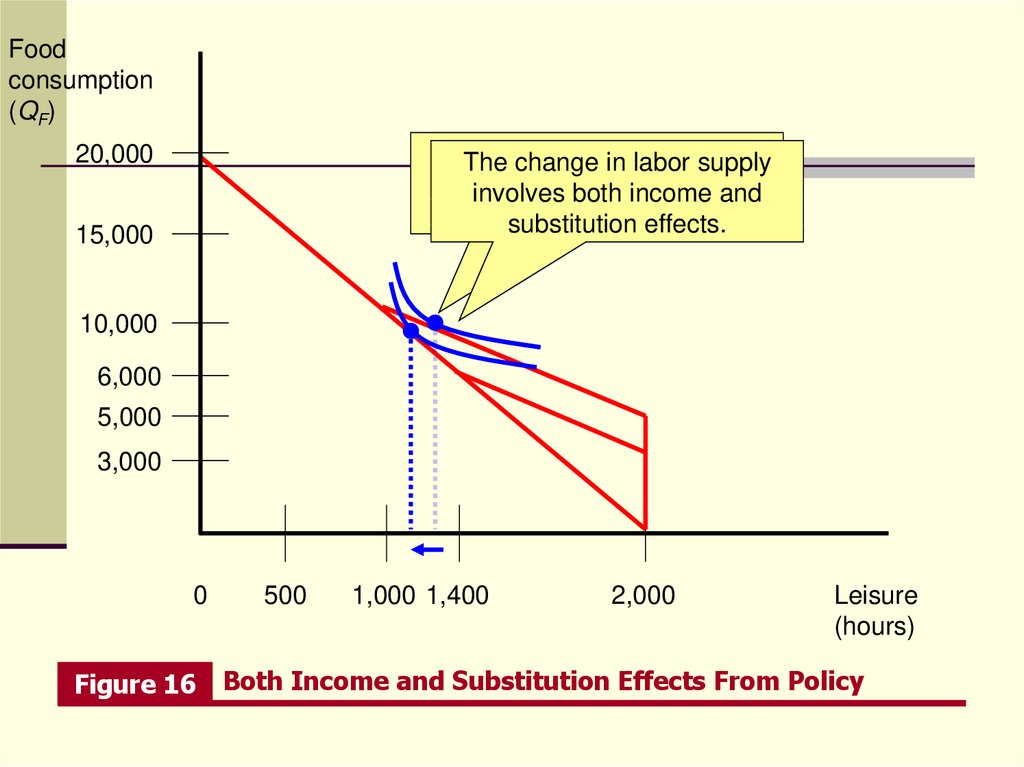

If she initially earned between $6,000 and $10,000per year, the policy change involves both an income

and substitution effect.

The substitution and income effects go in the same

direction.

Figure 16 illustrates this.

50.

Foodconsumption

(QF)

20,000

The change

effectiveinwage

The

laborrate

supply

changes

thisincome

person.

involvesfor

both

and

substitution effects.

15,000

10,000

6,000

5,000

3,000

0

Figure 16

500

1,000 1,400

2,000

Leisure

(hours)

Both Income and Substitution Effects From Policy

51. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK How large will the labor supply response be?

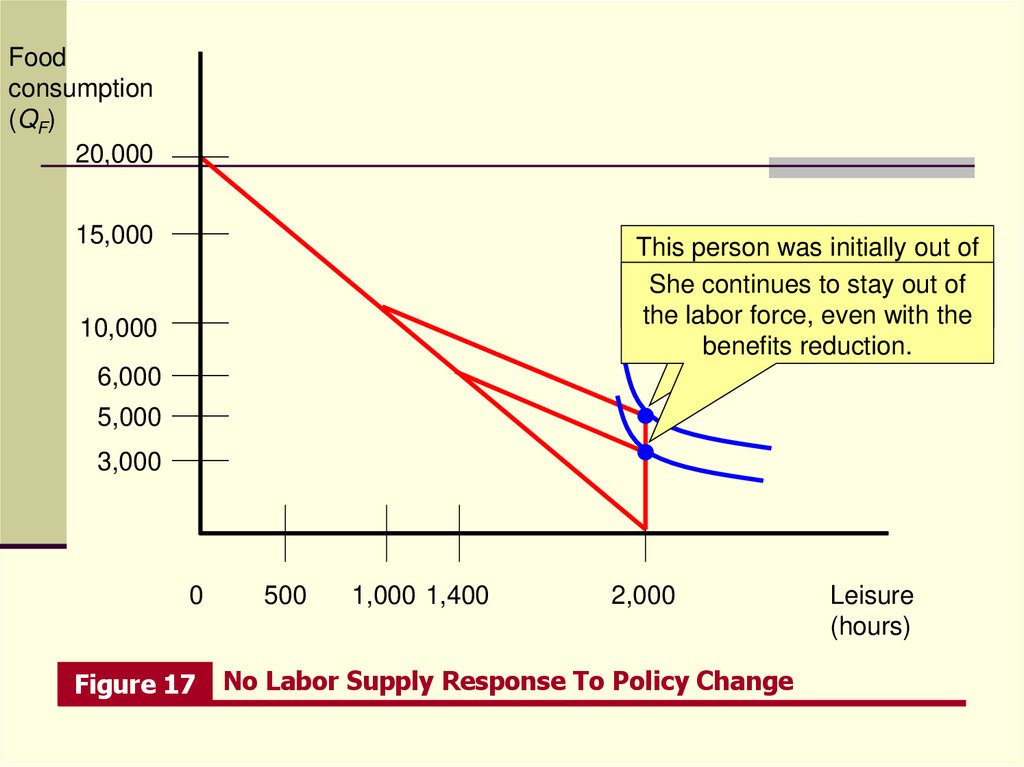

Economic theory clearly suggests that such a benefitreduction will increase labor supply, but does not

speak to the magnitude of the response.

For example, some welfare recipients who were not

initially working continue to choose not to work.

Figure 17 illustrates this.

52.

Foodconsumption

(QF)

20,000

15,000

This person was initially out of

the labortoforce.

She continues

stay out of

the labor force, even with the

benefits reduction.

10,000

6,000

5,000

3,000

0

Figure 17

500

1,000 1,400

2,000

No Labor Supply Response To Policy Change

Leisure

(hours)

53. PUTTING THE TOOLS TO WORK How large will the labor supply response be?

The actual magnitude of the labor supply responsetherefore depends on the preferences of various

welfare recipients.

To the extent the preferences are more like the first

two cases, the larger the labor supply response.

Thus, theory alone cannot say whether this policy

change will increase labor supply, or by how much.

Must analyze available data on single mothers to

figure out the magnitude.

54. WELFARE IMPLICATIONS OF BENEFIT REDUCTIONS: TANF continued

Efficiency and equity considerations in introducingor cutting TANF benefits.

In a typical labor supply/labor demand framework,

these changes shift the labor supply curve for single

parents.

Figure 27 illustrates this.

55.

WageEquilibrium

Inefficient,with

but generous

entails

substantial

TANF

redistribution.

benefit.

Entails

Equilibrium

some

redistribution

with TANF

w3

Labor

supply

Labor

supply

and some

benefit

inefficiency.

cut.

Equilibrium with no

government intervention,

no deadweight loss.

Labor

supply

w2

w1

Labor

demand

H3

Figure 27

H2

H1

Hours

worked

Market Equilibrium with Labor Supply and Demand

56. WELFARE IMPLICATIONS OF BENEFIT REDUCTIONS: TANF continued

Different policies involve different deadweight losstriangles, but also different levels of redistribution for the

poor.

SWF helps determine the right policy for society.

SWF U i

i

Is SWF the right objective?

Why its maximization might lead to an outcome that is not

efficient (why redistribution necessary)?

How to do it in practice?

Экономика

Экономика