Похожие презентации:

Maximizing the medical treatment of endometriosis, the double progestin system (DPS) for difficult endometriosis

1. Maximizing the medical treatment of endometriosis, the double progestin system (DPS) for difficult endometriosis

Moamar Al-Jefout MD, PhD2. Declaration

• I declare no conflict of interests3. Notion

Medical treatment should be the first linemodality for Deep Endometriosis (DE) in

women with pain symptoms

4. Facts

• No medical therapy is effective on all patientswith a chronic condition;

• Effective drugs with no side effects just do not

exist;

• Medications for chronic disorders are, by

definition, symptomatic.

• Rapid symptom recurrence at drug

discontinuation is expected

• “Inefficacy,” is defined as lack of symptom

relief during treatment and not after treatment

5. Current status regarding surgical Rx for DE

• For almost a century, the surgical treatment of endometriosis has been basedmainly on a straightforward oncologic principle, i.e. radical removal of lesions.

• Endometriotic deep lesions are benign and usually not progressive (Fedele L,

2004)

• The outcome and complications of surgical treatment for DE are difficult to

assess, because they are influenced by numerous variables including severity

of the disease, number and location of endometriotic nodules, degree of

infiltration of the bowel or the urinary tract and overall experience of the

surgical team

• There are no specific guidelines from any society regarding the indication and

surgical approach for bladder and bowel DE. (Kho, RM ., 2018)

• Currently, the general recommendation by ACOG, ESHRE, and SOGC for the

definitive treatment of pain associated with DE is still hysterectomy with or

without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in women with no desire for future

fertility, associated intractable pelvic pain, adnexal masses, or multiple

previous conservative surgical procedures

(G.A.J. Dunselman, 2014; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,

2010; N. Leyland, 2010)

6. Population-based data do not suggest that conservative surgery constitutes a durable remedy for severely symptomatic

endometriosis patients.• Weir et al. (2005) analysed the clinical records of 53 385 hospital

admissions for the treatment of endometriosis in the province of

Ontario, Canada, from 1994 to 2002.

• The records of 7993 patients with 15 years of age or older, with no

prior hospital admission for endometriosis in the preceding 2 years,

who underwent ‘minor’ or ‘intermediate’ conservative surgery for

early disease, constituted the base for a 4 year longitudinal study.

• During the observation period, the likelihood of hospital readmission for additional surgical treatment was 27% and that of

having a hysterectomy was 12%.

• However, in spite of a substantial risk of re-operation, operative

laparoscopy is increasingly performed for treating symptomatic

endometriosis.

• On the basis of large epidemiologic databases, it has been

estimated that ∼1 in 400 North American women aged 15–45 years

is hospitalized for surgical treatment of endometriosis each year

(Weir et al., 2005).

7. Recurrence of deep lesions after surgery

Recurrence of deep lesions

after surgery

A repeat procedure within 5 years from primary surgery because of recurrence of pain was

reported in about one in five women (19%) who underwent bowel resection (C. De

Cicco,2011)

The 24 month cumulative probability of moderate or severe dysmenorrhoea recurrence was

20% in the former group and 25% in the latter, without statistically significant differences.

Crosignani et al. (1996)

A similar rate of pain recurrence (22%), 2 years after laparoscopic surgery for stage III–IV

disease, was reported by Busacca et al. (1999) in a group of 141 patients.

Abbott et al. (2003) investigated the outcomes of laparoscopic excision of endometriosis up

to 5 years after surgery in 176 women with severe pain symptoms, the 5 year cumulative

probability of requiring further surgery was 36%.

Vignali et al. (2005) evaluated the risk of pain and disease recurrence after conservative

surgery for endometriosis in a series of 115 women with deep lesions. After a minimum

follow-up of 12 months, recurrence of pain was observed in 28 patients (24%) and

recurrence of lesions in 15 (13%). Twelve subjects (10%) underwent repetitive surgery.

Multivariate analysis demonstrated that only age was a significant predictor of pain

recurrence, enhancing the risk in younger patients. Recurrence of lesions was predicted by

obliteration of the Douglas pouch and re-operation was predicted by non-radical first-line

surgery.

8. Recurrence after surgery

• NICE Committee maintained “in view of the high rateof recurrence of endometriosis, affecting long-term

quality of life for many women, improvement in longterm control of the condition was felt by the

Committee to be clinically very important.

• The Committee were aware of the high rate of

reoperation for endometriosis with associated risks of

surgery and, as there was strong evidence to support

this, considered that avoidance of repeat surgery by

the use of long -term medical therapy would be

beneficial.

9. Impact of endometriosis on risk of further gynaecological surgery: a national cohort study

• The incidence of subsequent gynaecological surgery wassignificantly higher in women with endometriosis (n = 11

052; 62%) when compared with women with no evidence

of endometriosis at laparoscopy (n = 42 136; 50.6%),

women who had undergone laparoscopic sterilisation (n =

58 704; 36%) and age‐matched women from the general

population (n = 2907; 16.3%).

• The median (IQR) time for a second surgical procedure

(after the initial diagnostic operation) for the endometriosis

group was less than 2 years [1.8 (0.8, 4.6)], which was

significantly shorter than the corresponding period in

women in the three unexposed groups. Half of all women

with endometriosis had undergone repeat surgery within

5.5 years.

L Saraswat D Ayansina KG Cooper S Bhattacharya AW Horne S

Bhattacharya 2017 BJOG

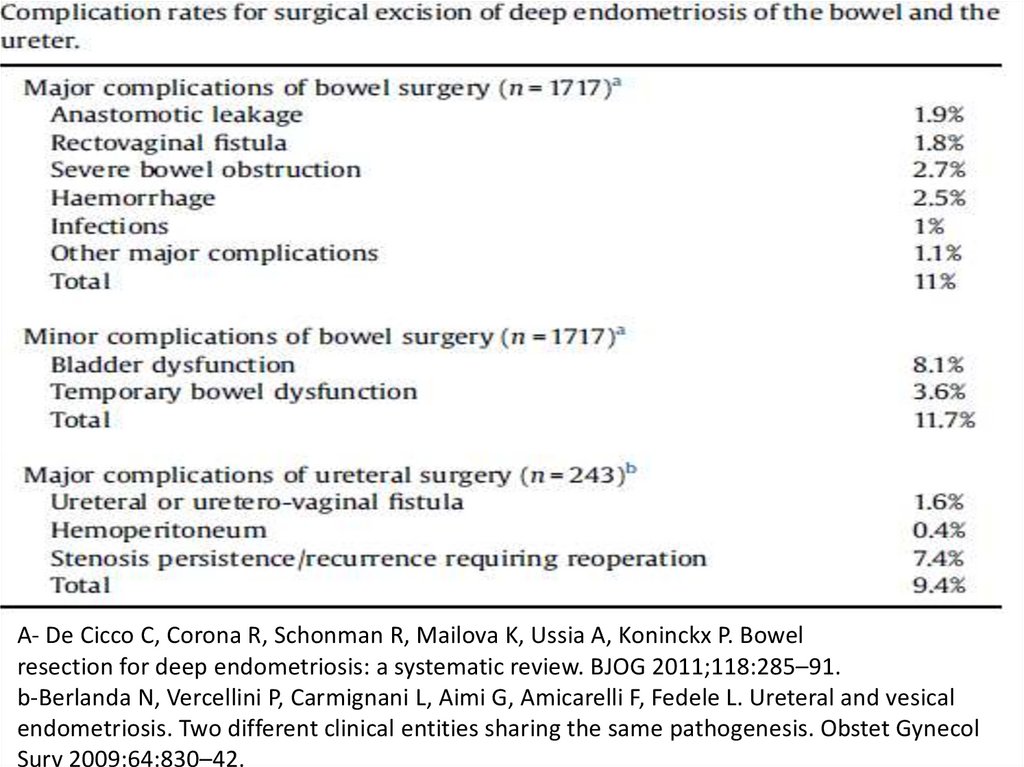

10. Complications of surgery for DE

• The overall complication rate was 24%, and the severe complicationrate (i.e., Clavien-Dindo IIIB) was 3% (n = 4). (Jayot, Aude, 2020)

• A recent systematic review revealed a 6.3% rate of major

complications following bowel endometriosis resection, including:

– Transient urinary retention: The most frequently reported postoperative difficulty is urinary retention, probably due to damage to the

parasympathetic plexus resulting in temporary bladder denervation.

This problem is associated with, but it is not exclusive to, colorectal

resection (Dubernard et al., 2008).

– Fistula: with a reported risk as high as 10% even in expert hands (Darai

et al., 2005; Dubernard et al., 2006).

– Anastomotic leakage (0.8% of cases).

– Anastomotic stricture (6.3%) of a total of 1643 patients who

underwent laparoscopic rectosigmoid resection. Protective ileostomy

is the sole modifiable factor related to anastomotic stenosis

(Bertocchi, E, 2019).

• Many women prefer to live with residual dyschezia than to risk a

fecaloid fistula or a derivative colostomy.

11. A- De Cicco C, Corona R, Schonman R, Mailova K, Ussia A, Koninckx P. Bowel resection for deep endometriosis: a systematic

review. BJOG 2011;118:285–91.b-Berlanda N, Vercellini P, Carmignani L, Aimi G, Amicarelli F, Fedele L. Ureteral and vesical

endometriosis. Two different clinical entities sharing the same pathogenesis. Obstet Gynecol

Surv 2009;64:830–42.

12. So what advice could we sensibly give women who need to decide on whether they opt for surgical treatment of lower bowel

endometriosis?• Until we have robust data, it is difficult to provide women with

accurate information about the surgical risk.

• Based on the larger studies in the review by De Cicco et al., we can

advise that the chances of having a major surgical complication are

probably around 10%.

• The case series of Kondo et al. suggests that the major complication

rate is likely to be lower in women undergoing a mucosal skimming

procedure relative to those having a segmental resection.

• Women also need to be advised that the complication rate may be

higher in units that have relatively little experience of this surgery

and, as recommended by the Royal College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists (RCOG), the surgeon should quote his/her own

complication rate.

De Cicco C, 2011; Kondo W, 2011; Royal College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists. 2008

13.

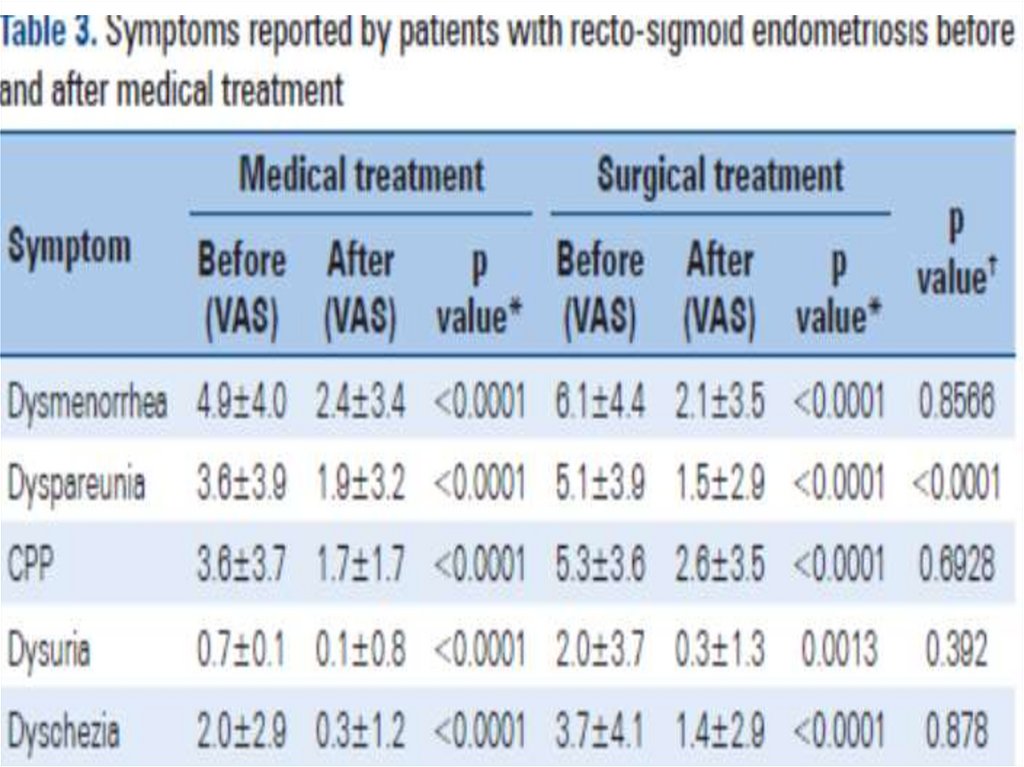

Medical rx for endometriosis14. Medical treatment for DE (Andres,MP, 2019)

• Methods: Retrospective study based on data extracted frommedical records of 238 women with recto-sigmoid endometriosis.

• Results: Over the course of follow-up, 143 (60.1%) women

remained in medical treatment while 95 (39.9%) presented with

worsening of pain symptoms or intestinal lesion growth (failure of

medical treatment group), with surgical resection performed in 54

cases.

• Conclusion: Patients with recto-sigmoid endometriosis who failed

to respond to medical treatment were younger and had larger

intestinal lesions. Hormonal therapy was equally efficient in

improving pain symptoms other than dyspareunia compared to

surgery, and was associated with lower complication rates in

women with recto-sigmoid endometriosis.

• Medical treatment should be offered as a first-line therapy for

patients with bowel endometriosis. Surgical treatment should be

reserved for patients with pain symptoms unresponsive to

hormonal therapy, lesion growth or suspected intestinal

subocclusion.

15.

16.

17.

18. Symptom progression in patients with recto-sigmoid endometriosis submitted to medical or surgical treatment

19. Factors to be considered before treatment plan decision for DE

• Severity of symptoms• Size of the lesions

• Pain symptoms unresponsive to hormonal

therapy,

• Lesion growth or suspected intestinal

subocclusion.

• Age of the patient- younger patients seems to

have more recurrence

• BMI- high BMI is associated with recurrence

• Feasibility of surgery

20. A lesion-based, three-tiered risk stratification system

• a. Low-risk lesion: superficial peritoneal implantsprogressed in only one third of women- may be bettercandidates for treatment with OCs rather than

with progestogen monotherapies.

• b.Medium-risk lesions: Ovarian endometriomas-low

association with malignancy, typically less than 0.8%asymptomatic endometriomas do not require intervention

for infertility- low-dose OCs, used cyclically or continuously.

• High-risk lesions: Deep fibrotic nodules- Progestogens,

instead of OCs, should generally be considered the first-line

medical treatment- two-thirds of patients with deep

endometriosis respond favorably to progestogen treatment

P. Vercellini, 2016

21. A symptom-based, stepped-care approach

• NICE Committee confirmed two fundamental principles (1):• (1) “all treatments led to a clinically significant reduction in

pain on the VAS when compared to placebo. The magnitude

of this treatment effect was similar for all treatments,

suggesting that there was little difference between them in

their capacity to reduce pain. No other significant

differences were found between the hormonal treatments”;

and

• (2) “it is known that there are a cluster of extremely cheap

hormonal treatments (including the combined oral

contraceptive pill) and a cluster of extremely high-cost

treatments including dienogest and GnRHas”

1- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017

22. A symptom-based, stepped-care approach

• low-dose OCs should be used cyclically in women withperitoneal and ovarian endometriosis, stepping up to

continuous use with tailored cycling only in those

women with persistent dysmenorrhea despite cyclic OC

use.

• In case of inefficacy on pain during OC use, patients

should step up to a low-cost progestogen such as NETA.

• Starting directly with a low-cost progestogen should be

considered in patients with deep lesions or with

deep dyspareunia as their main complaint.

• In case of inefficacy of or intolerance to progestogens,

patients may step up to GnRH-agonists or antagonists

23. The goal of endometriosis therapy

• “the goal of endometriosis therapy shouldalways be absence of pain; if this end point is not

achieved with oral contraceptives, the patient

should be offered more definitive therapy. Many

patients fail to adequately respond to oral

contraceptives while others develop progestin

resistance with disease progression despite using

a progestin based therapy […] The realization that

all therapies have different efficacy and the

availability of new endometriosis drugs will allow

more rapid progression to definitive therapy”

H.S. Taylor, 2017

24. The burden of illness and the burden of treatment

• The burden of illness: Women with severely symptomaticendometriosis, in addition to pain, usually experience

major worsening in health-related quality of life,

psychological status, sexual functioning and marital

relationship, social life, and school or work productivity.

• The burden of treatment: endometriosis, includes taking

medications, managing side effects, attending gynecologic

visits, performing imaging investigations and repeated

blood tests, undergoing surgical procedures, selfmonitoring, lifestyle changes, administrative task to access

and coordinate care, full or partial payment of treatments,

and other hidden costs.

G. Spencer-Bonilla, 2017

25. Pros and cons of combined oral contraceptives

• In a large, multicenter, placebo-controlled RCT conducted in womenwith symptomatic endometriosis, a low-dose oral contraceptive (OC)

substantially improved not only dysmenorrhea but also other pain

symptoms including nonmenstrual pain and deep dyspareunia (1).

• However, Casper suggested that progestogens should be preferred to

OCs as a first-line treatment, based on the consideration that

estrogen and progesteron receptors would be, respectively, over- and

underexpressed in ectopic endometrial implants- potential risk of

lesion progression (2).

• The currently available epidemiological data do not support a

pathogenic role of OCs in the development of endometriosis (3)

• OCs when chosen as a modality to manage endometriosis,

combinations with the lowest possible estrogen dose should be

chosen, such as those with only 15–20 μg of EE or 1.5 mg of 17 βoestradiol (E2)

1- T. Harada, 2017. 2- R.F. Casper, 2017. 3- P. Vercellini, 2011

26. Use of OCs continuously instead of cyclically!!

• When pooling published data, no statistically significantdifferences were observed between the two treatment

schedules in other pain symptoms as well as in

postoperative ovarian endometrioma recurrence rate (1).

• Using OC continuously increases the likelihood of erratic

bleeding that, if not promptly dealt with by tailored

cycling (2), may cause prolonged pain (3)

• Cyclic OC use may increase therapeutic compliance in

patients (amenorrhea).

• Continuous and tricycling (where three packets are taken in

a row, followed by a pill free interval) may be the best

approach (4)

1- L. Muzii, 2014. 2- T. Harada, 2017. 3- P. Vercellini, 2013.

4- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence,2017

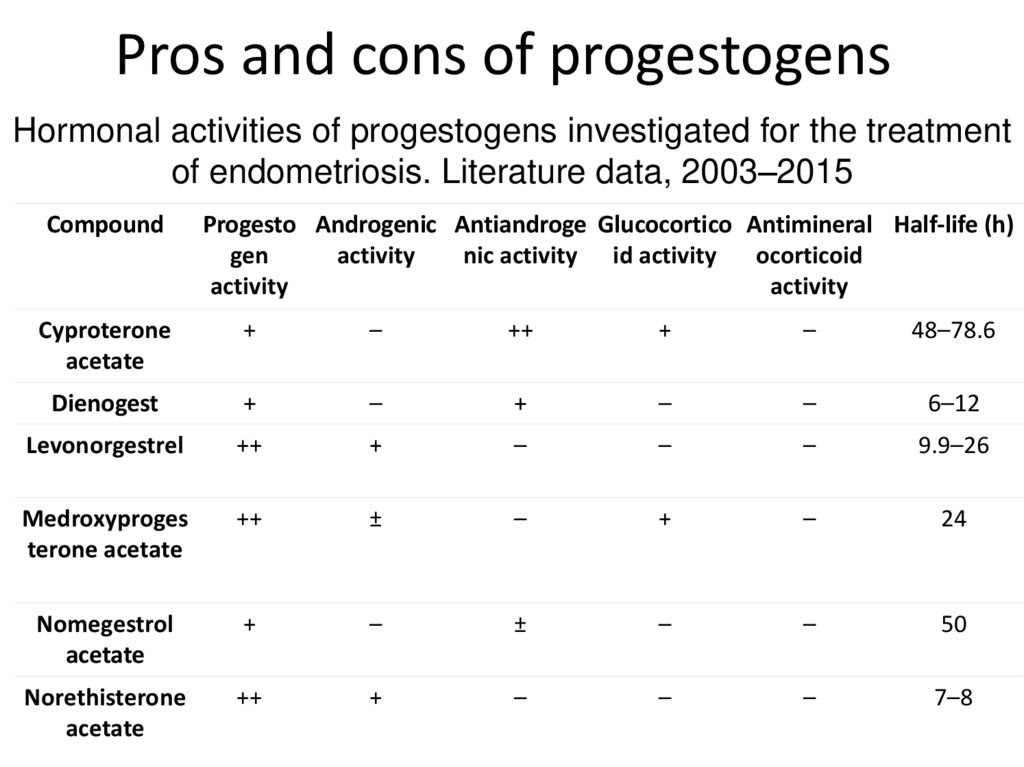

27. Pros and cons of progestogens

Hormonal activities of progestogens investigated for the treatmentof endometriosis. Literature data, 2003–2015

Compound

Progesto Androgenic Antiandroge Glucocortico Antimineral Half-life (h)

gen

activity

nic activity id activity

ocorticoid

activity

activity

Cyproterone

acetate

+

–

++

+

–

48–78.6

Dienogest

+

–

+

–

–

6–12

Levonorgestrel

++

+

–

–

–

9.9–26

Medroxyproges

terone acetate

++

±

–

+

–

24

Nomegestrol

acetate

+

–

±

–

–

50

Norethisterone

acetate

++

+

–

–

–

7–8

28. Cost of progestogens

• Low-cost progestogens includemedroxyprogesterone acetate (MAP),

norethisterone acetate (NETA), levonorgestrel

(LNG), and nomegestrol acetate (NOMAC).

• Dienogest (DNG) is the only high-cost

progestogen currently licensed for the

treatment of endometriosis.

29.

“Every woman is unique and so is her responseto progestogen, hence, we need to explore

which progestin suites each woman”

Al-Jefout Moamar

30. GnRH agonists

• The profound hypoestrogenic state achievedduring the use of these drugs explains their

efficacy in terms of pelvic pain relief and, at the

same time, their limited tolerability and safety.

• The combination of GnRH agonists with add-back

therapy (generally, a bone-sparing progestogen

such as NETA or an estrogen–progestogen

hormone replacement therapy) limits vasomotor

side effects and prevents bone resorption, but

further increases costs

31. GnRH antagonist-Elagolix,

• The GnRH antagonist at the oral daily dose of 150 or 400 mg was tested against aplacebo.

• At 3-month evaluation- a clinical response with respect to dysmenorrhea were 43–

46% and 72–76% in the lower- and the higher-dose elagolix group, respectively,

• At the end of the 6-month study period, the percentage of participants

experiencing amenorrhea in the high-dose elagolix group in the two trials varied

from 47% to 66%.

• Hot flushes - reported by 42–48% of women in the high-dose elagolix group.

• The mean percent bone mineral density (BMD) reduction at the lumbar

spine observed at 6-month follow-up in women in the high-dose elagolix group

varied from −2.49 to −2.61.

• Therefore, unless GnRH antagonists will be marketed at a price lower than that of

GnRH agonists, the advantages of the former compounds over the latter ones may

reveal smaller than expected.

• Unplanned pregnancy rate in women who used elagolix was over 1% (6/497)

H.S. Taylor, 2017

32.

Dual progestogen-delivery system (DPS)therapy with levonorgestrel intrauterine

system and etonogestrel subdermal implant for

severe and persistent endometriosis-associated

pelvic pain: An effective new therapy.

• Cecilia Hoi Man Ng (PhD), Anthony James Marren (FRANZCOG), Ian

Stewart Fraser (MD, DSc), Angela Pardey (MBBS), John Pardey (MBBS) and

Moamar Ibrahim Al-Jefout (MD, PhD)

33.

34. DPS (Dual progestogen-delivery System) for refractory endometriosis

• Objective: To explore the usefulness ofsimultaneous use of dual progestogendelivery systems (DPS) with the LNG-IUS and

etonogestrel subdermal implant (ESI) as a new

combination therapy for severe, refractory

endometriosis-associated pelvic pain

35. Women refractory to conventional therapies

• Management of endometriosis depends primarily on whether thewoman wishes to conceive or not.

• The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), the

European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE)

and the World Endometriosis Society (WES) have developed

comprehensive consensus statements for the management of

chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis. Other organizations have

also developed detailed evidence-based reviews of management

(e.g. Cochrane Collaboration).

• These have all tried to offer sound, evidence-based

recommendations from randomized trials on large numbers of

women.

• However, little attention has been given specifically to that small

group of women with refractory symptoms who have responded

poorly to more conventional therapies.

36. LNG-IUS & etonogestrel subdermal implant for endometriosis

LNG-IUS & etonogestrel subdermalimplant for endometriosis

• Recently, there has been a gradual move towards greater use of

local delivery of progestogen via LNG-IUS; Mirena®, which delivers

levonorgestrel into the uterine cavity at a steady rate of 20 mg/day

from the time of insertion.

• It has been demonstrated to be an effective therapy in the

prevention of recurrence of endometriosis following laparoscopic

treatment, as well as moderately effective in control of pain

symptoms in many women with endometriosis.

• There has also been occasional use of a systemic but constant

delivery of progestogen through the etonogestrel subdermal

implant (ESI; Implanon®, which delivers etonogestrel at a steady

initial rate of 60 – 70 mg/day into the systemic circulation.

• It has been reported that the ESI may be effective in improving

primary dysmenorrhea and also pelvic pain associated with

endometriosis.

37. Rational for combination

• When both systems are combined a steady low-dose delivery ofprogestogens is maintained that should offer simultaneous dual

targeting of local uterine and more distant lesions, as well as

preventing new lesions from forming.

• A constant local and systemic combined delivery of progestogen

offered by the LNG-IUS and ESI should offer a logical extension of

conventional hormonal treatment of “difficult” endometriosis.

• Simultaneous use of the LNG-IUS and the ESI for a case of

debilitating adolescent endometriosis was first reported by AlJefout, et al. 2009.

• The case study of a 13-year-old female with pelvic pain secondary

to endometriosis, refractory to a series of conventional medical and

conservative surgical therapies and whose life was completely

dominated by the persistent pain of endometriosis.

• In this case a combination of LNG-IUS and ESI proved to be a highly

effective dual therapy, allowing her to return to school studies and

a completely normal lifestyle.

38. Ethics approval & Indications for the combined therapy

Ethics approval & Indications for thecombined therapy

• This retrospective case series was approved by

the Ethics Review Committees from Royal Prince

Alfred Hospital, Sydney and the University of

Sydney.

• The patients, and where relevant, their parents,

gave informed consent to undertake this off-label

therapy

• Prior to the insertion of the DPS, all women had

undergone a series of attempts at various

medical and/or surgical treatments, without

satisfactory control of symptoms

39. DPS

• Objective: To explore the usefulness ofsimultaneous use of dual progestogen-delivery

systems (DPS) with the LNG-IUS and etonogestrel

subdermal implant (ESI) as a new combination

therapy for severe, refractory endometriosisassociated pelvic pain.

• Methods: This report details the very successful

simultaneous use of LNG-IUS and ESI for

debilitating and refractory endometriosis in 40

women with refractory pelvic pain secondary to

endometriosis.

40. Results:

• The mean duration of use of the DPS was 28.1 (range 9 – 98) months.• The mean age at first review was 25.2 (range 13 – 50) years. The mean

duration of symptomatology was 7.9 (range 0.5 – 30) years – 39/40

recorded dysmenorrhea; 16/19 deep dyspareunia; 12/40 dyschezia;

and 4/40 dysuria; 16/40 recorded additional symptoms (e.g. heavy

menstrual bleeding, erratic pelvic pain, and painful abdominal

bloating).

• A small proportion of the teenagers (n = 4; 10% of the total) could be

classified as “dramatic” improvement, defined as the development of

amenorrhea with no pelvic pain. “Marked” improvement, as defined by

the major resolution of most symptomatology was reported in 26/40

(65%).

• Three had a “borderline” initial response (i.e. some improvement in

symptoms) but then obtained marked and ongoing improvement after

short-term supplementation with an oral progestogen or 3 months of a

GnRH analogue.

• Persistent borderline benefit was reported in 5/40 (13%).

41. Conclusions:

• The combination DPS appears to be aneffective new medical option in management

of refractory endometriosis-associated pelvic

pain. This DPS is a promising, sustainedrelease approach for severe, persistent

endometriosis pain, especially in young

women.

Медицина

Медицина