Похожие презентации:

Anglo-Boer War

1.

Anglo-Boer War2.

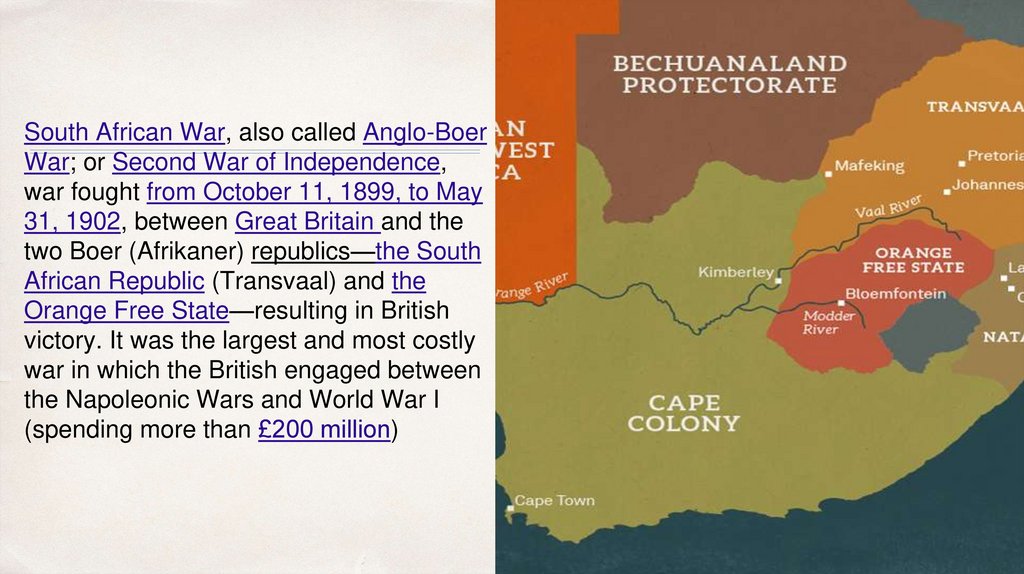

South African War, also called Anglo-BoerWar; or Second War of Independence,

war fought from October 11, 1899, to May

31, 1902, between Great Britain and the

two Boer (Afrikaner) republics—the South

African Republic (Transvaal) and the

Orange Free State—resulting in British

victory. It was the largest and most costly

war in which the British engaged between

the Napoleonic Wars and World War I

(spending more than £200 million)

3.

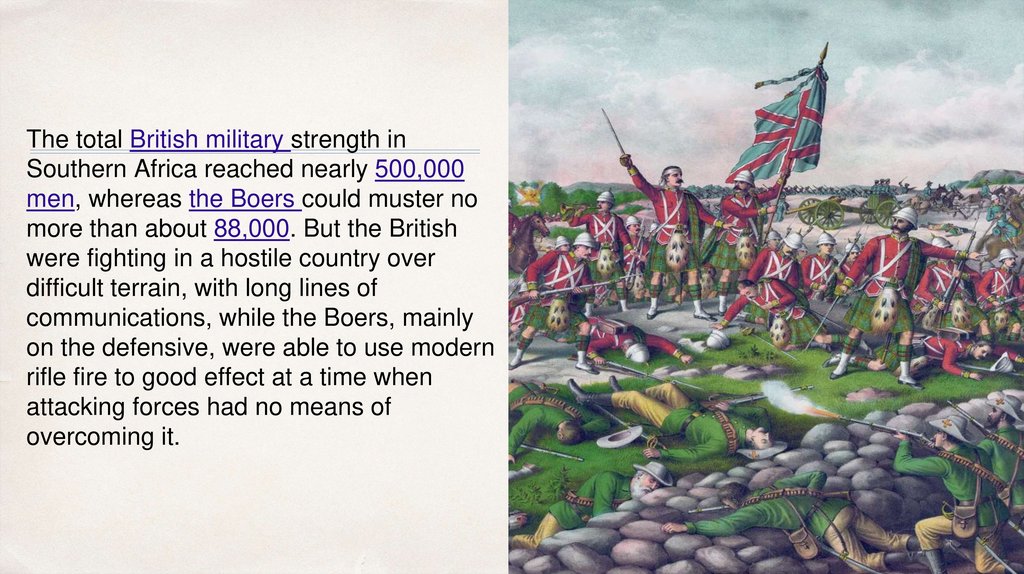

The total British military strength inSouthern Africa reached nearly 500,000

men, whereas the Boers could muster no

more than about 88,000. But the British

were fighting in a hostile country over

difficult terrain, with long lines of

communications, while the Boers, mainly

on the defensive, were able to use modern

rifle fire to good effect at a time when

attacking forces had no means of

overcoming it.

4.

Underlyingcauses

5.

The causes of the war have provokedintense debates. British politicians claimed

they were defending their “suzerainty” over

the South African Republic (SAR)

enshrined in the Pretoria and (disputably)

London conventions of 1881 and 1884,

respectively. It was the largest gold-mining

complex in the world. Also, the discovery of

gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886 allowed

the SAR to make progress with

modernization efforts and vie with Britain for

domination in Southern Africa.

6.

After 1897 Britain—through Alfred Milner,its high commissioner for South demanded

the modification of the Boer republic’s

constitution to grant political rights to the

primarily British Uitlanders, thereby

providing them with a dominant role in

formulating state policy.

(photo: Lord Alfred Milner)

7.

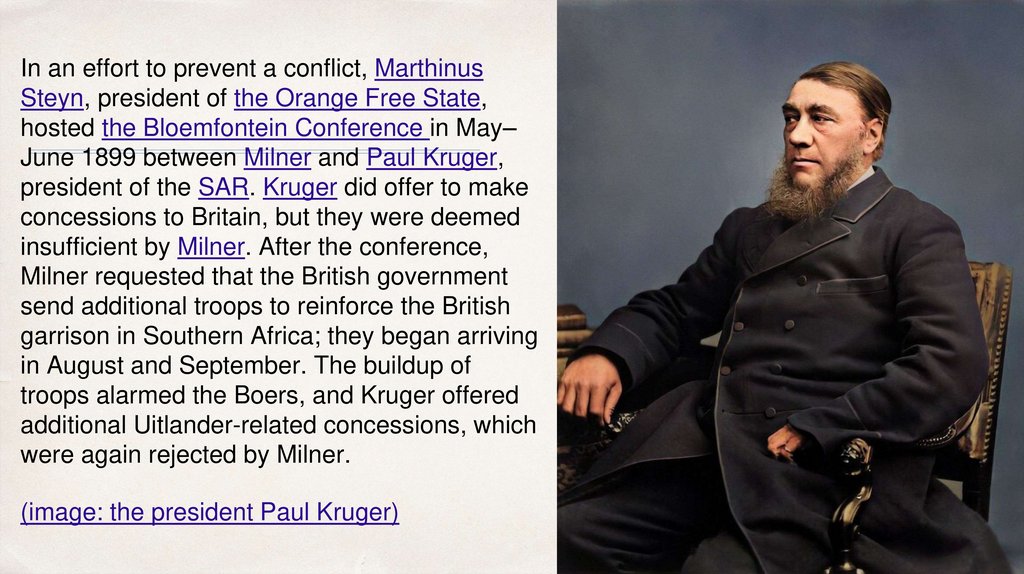

In an effort to prevent a conflict, MarthinusSteyn, president of the Orange Free State,

hosted the Bloemfontein Conference in May–

June 1899 between Milner and Paul Kruger,

president of the SAR. Kruger did offer to make

concessions to Britain, but they were deemed

insufficient by Milner. After the conference,

Milner requested that the British government

send additional troops to reinforce the British

garrison in Southern Africa; they began arriving

in August and September. The buildup of

troops alarmed the Boers, and Kruger offered

additional Uitlander-related concessions, which

were again rejected by Milner.

(image: the president Paul Kruger)

8.

The Boers, realizing war was unavoidable,took the offensive. On October 9, 1899, they

issued an ultimatum to British government,

declaring that a state of war would exist

between Britain and the two Boer republics if

the British did not remove their troops from

along the border. The ultimatum expired

without resolution, and the war began on

October 11, 1899.

(image: the Bloemfontein Conference)

9.

WARInitial Boer success

10.

During the first phase of war, the British inSouthern Africa were unprepared and militarily

weak. Boer armies attacked on two fronts: into

the British colony of Natal from the SAR and

into the northern Cape Colony from the Orange

Free State. The northern districts of the Cape

Colony rebelled against the British and joined

the Boer forces. In late 1899 and early 1900,

the Boers defeated the British in a number of

major engagements and besieged the key

towns of Ladysmith, Mafeking (Mafikeng), and

Kimberley. Particularly of note among Boer

victories in this period are those that occurred

at Magersfontein, Colesberg, and Stormberg,

during what became known as Black Week

(December 10–15, 1899).

11.

British resurgence12.

In the second phase the British, under LordsKitchener and Roberts, relieved the besieged

towns, beat the Boer armies in the field, and

rapidly advanced up the lines of rail

transportation. Bloemfontein (capital of the

Orange Free State) was occupied by the

British in February 1900, Johannesburg and

Pretoria (capital of the SAR) in May and June.

Kruger evaded capture and went to Europe,

where, despite the fact that there was much

sympathy for the plight of the Boers, he was

unsuccessful in his attempts to gain viable

assistance in the fight against the British.

13.

Boer guerrillawarfare and British

response

14.

At the end of 1900 the war entered uponits most destructive phase. For 15 months,

Boer commandos, under the brilliant

leadership of generals such as Christiaan

Rudolf de Wet and Jacobus Hercules de

la Rey, held British troops at bay, using

hit-and-run guerrilla tactics. They harried

the British army bases and

communications, and large rural areas of

the SAR and the Orange Free State

(which the British had annexed as the

Crown Colony of the Transvaal and the

Orange River Colony, respectively)

remained out of British control.

15.

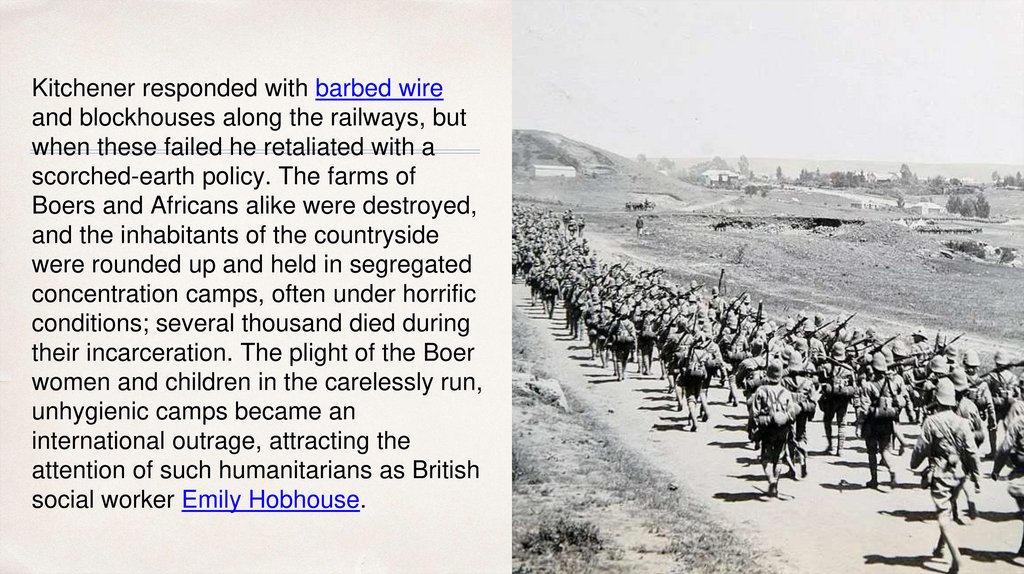

Kitchener responded with barbed wireand blockhouses along the railways, but

when these failed he retaliated with a

scorched-earth policy. The farms of

Boers and Africans alike were destroyed,

and the inhabitants of the countryside

were rounded up and held in segregated

concentration camps, often under horrific

conditions; several thousand died during

their incarceration. The plight of the Boer

women and children in the carelessly run,

unhygienic camps became an

international outrage, attracting the

attention of such humanitarians as British

social worker Emily Hobhouse.

16.

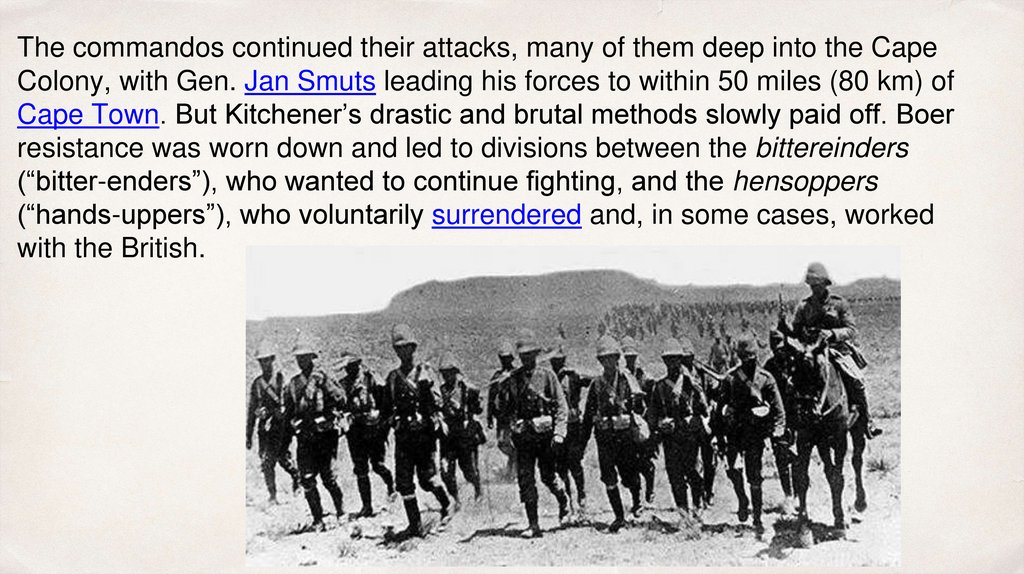

The commandos continued their attacks, many of them deep into the CapeColony, with Gen. Jan Smuts leading his forces to within 50 miles (80 km) of

Cape Town. But Kitchener’s drastic and brutal methods slowly paid off. Boer

resistance was worn down and led to divisions between the bittereinders

(“bitter-enders”), who wanted to continue fighting, and the hensoppers

(“hands-uppers”), who voluntarily surrendered and, in some cases, worked

with the British.

17.

Peace18.

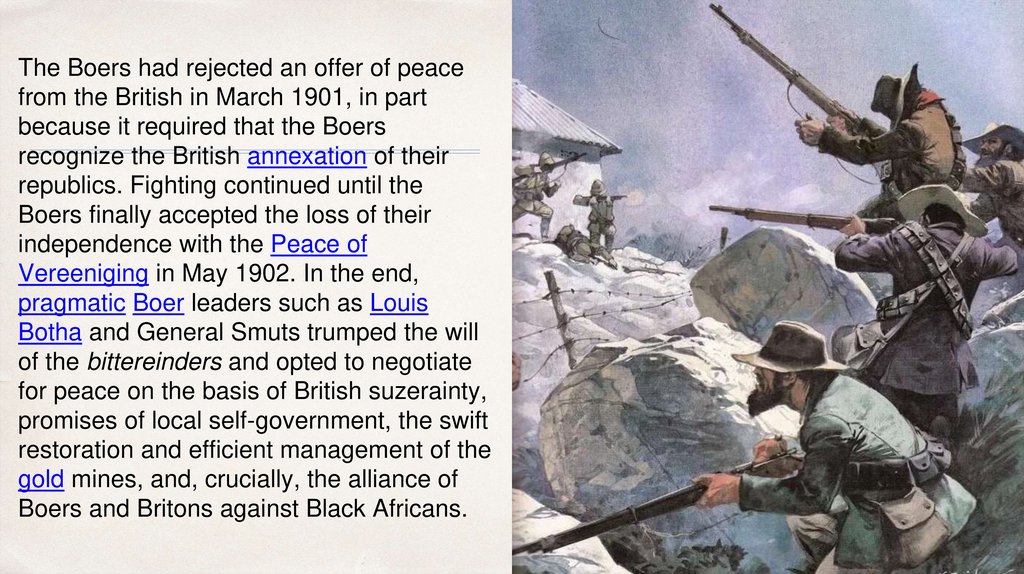

The Boers had rejected an offer of peacefrom the British in March 1901, in part

because it required that the Boers

recognize the British annexation of their

republics. Fighting continued until the

Boers finally accepted the loss of their

independence with the Peace of

Vereeniging in May 1902. In the end,

pragmatic Boer leaders such as Louis

Botha and General Smuts trumped the will

of the bittereinders and opted to negotiate

for peace on the basis of British suzerainty,

promises of local self-government, the swift

restoration and efficient management of the

gold mines, and, crucially, the alliance of

Boers and Britons against Black Africans.

19.

Assessment20.

In terms of human life, nearly 100,000lives were lost, including those of

more than 20,000 British troops and

14,000 Boer troops. Noncombatant

deaths include the more than 26,000

Boer women and children estimated

to have died in the concentration

camps from malnutrition and disease;

the total number of African deaths in

the concentration camps was not

recorded, but estimates range from

13,000 to 20,000.

21.

On both sides the war produced heights ofnational enthusiasm of a type that marked the

era and culminated in frenetic British

celebrations after the relief of the Siege of

Mafeking in May 1900. (The word mafficking,

meaning wild rejoicing, originated from these

celebrations.) Despite attempts at rapid healing

of the wounds after 1902 and a willingness to

cooperate for the purpose of uniting against

Black Africans, relations between Boers (or

Afrikaners, as they became known) and

English-speaking South Africans were to remain

frigid for many decades. Internationally, the war

helped poison the atmosphere between

Europe’s great powers, as Britain found that

most countries sympathized with the Boers.

22.

The most astonishing aspect of the war, perhaps, is that it was a war between groups of white peoples in asubcontinent with a largely Black African population that both sides generally sought to exclude from the

fighting, although research in the later decades of the 20th century indicated that Black Africans became heavily

involved in the war both as combatants and as victims of the armies. During the conflict the British hinted and

sometimes promised that in return for support, or at least neutrality, Black Africans would be rewarded with

political rights after the war. Nevertheless, the Treaty of Vereeniging specifically excluded Black Africans from

having political rights in a reorganized South Africa as the British and Boers cooperated toward a common goal

of white minority rule.

23.

Interesting facts24.

This war was the first war of the 20th century and isinteresting from a variety of points of view.

✤

For example, both conflicting parties massively used

smokeless gunpowder, rapid-fire guns, shrapnel,

machine guns and magazine rifles, which forever

changed the tactics of the infantry, forcing them to hide

in trenches and trenches, attack in sparse chains

instead of the usual formation and, having remove

bright uniforms, put up in khaki..

✤

This war also "enriched" us with such concepts as

sniper, commandos, sabotage war, scorched earth

tactics and concentration camp.

25.

✤It was not only the first "attempt to bring

Freedom and Democracy" to mineral-rich

countries. But also, probably, the first war,

where the fighting, in addition to the battlefield,

was transferred to the information space. After

all, by the beginning of the 20th century,

humanity had already made good use of

telegraph, photography and cinema, and the

newspaper has become a familiar attribute of

every home.

✤

Thanks to all of the above, a philistine around

the world could learn about changes in the

military situation within just a few hours. And

not just to read about events, but also to see

them

in

photos

and

screens

of

cinematographs.

История

История