Похожие презентации:

Sociolinguistic Variation of the English Language

1. Sociolinguistic Variation of the English Language

Lecture № 1LOGO

2. Contents

1.1. Sociolinguistics: its aim, object and ties with other humanities1.2. Types of sociolinguistics

1.3. Language variation

1.4. Aspects of language competence

1.5. Methods employed by sociolinguistics

3. 1.1. Sociolinguistics: its aim, object and ties with other humanities

Miriam MeyerhoffAs it is written by Miriam

Meyerhoff in the introduction to

her book

“If I had a penny for every time I

have tried to answer the

question, ‘So what is

sociolinguistics?’, I would be

writing this book in the comfort

of an early retirement. And if

there was a way of defining it in

one simple, yet comprehensive,

sentence, there might not be a

need for weighty introductory

textbooks.”

4. 1.1. Sociolinguistics: its aim, object and ties with other humanities

Sociolinguistics is a branchof linguistics studying the

language in connection with

the social conditions of its

existence.

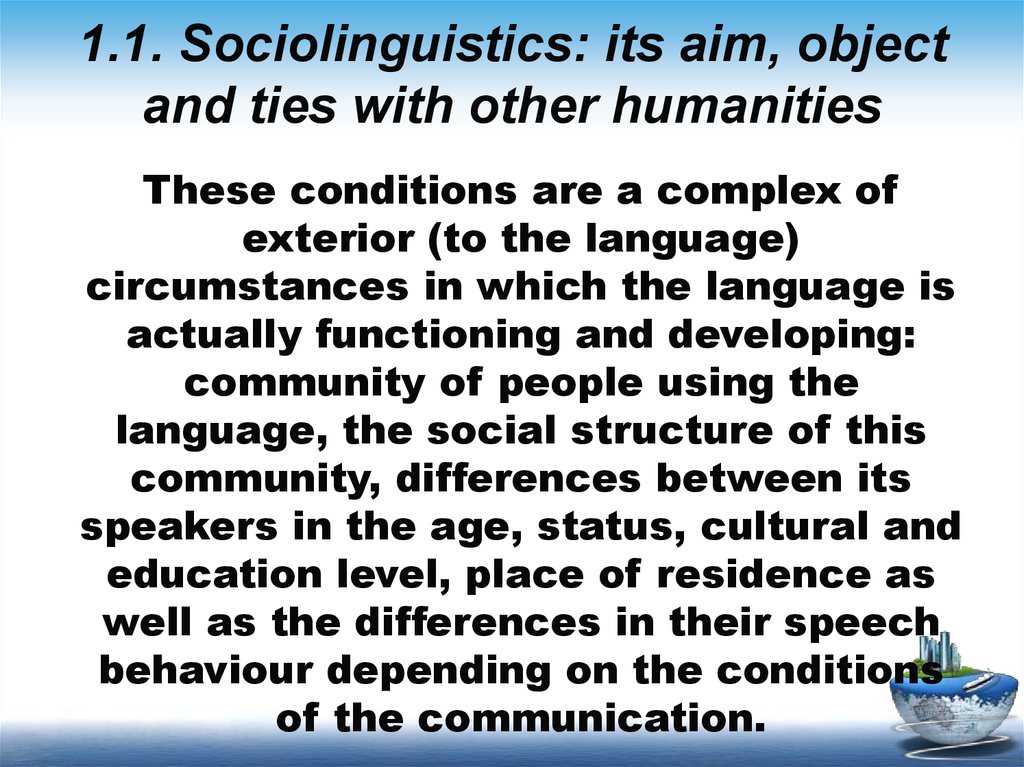

5. 1.1. Sociolinguistics: its aim, object and ties with other humanities

These conditions are a complex ofexterior (to the language)

circumstances in which the language is

actually functioning and developing:

community of people using the

language, the social structure of this

community, differences between its

speakers in the age, status, cultural and

education level, place of residence as

well as the differences in their speech

behaviour depending on the conditions

of the communication.

6. 1.1. Sociolinguistics: its aim, object and ties with other humanities

The term “Sociolinguistics” appears to havebeen first used in 1952 by Haver Currie, a poet

and philosopher who noted the general absence

of any consideration of the social in the linguistic

research of his day

7. 1.1. Sociolinguistics: its aim, object and ties with other humanities

William Labov, a prominent Americansociolinguist, “the father” of

sociolinguistic experiment, defines

sociolinguistics as a humanity that

studies “the language in its social

context”.

This means that the attention of

sociolinguistics is centered neither on

the language itself, nor on its inner

structure, but on the way it is used by

people belonging to this or that society.

8. Aims of sociolinguistics

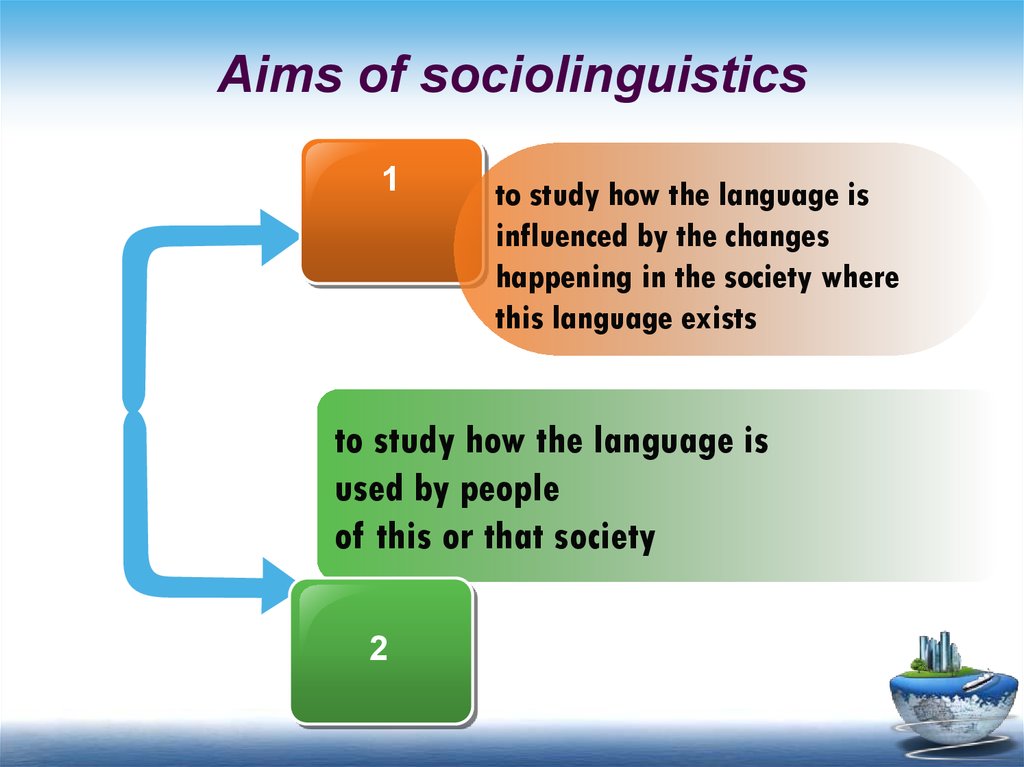

1to study how the language is

influenced by the changes

happening in the society where

this language exists

to study how the language is

used by people

of this or that society

2

9. 1.1. Sociolinguistics: its aim, object and ties with other humanities

There are many interconnections betweensociolinguistics and other disciplines

Scholars from a variety of

other disciplines have an

interest here, e.g.,

anthropologists, psychologists,

educators, and language

planners.

10. 1.2. Types of sociolinguistics

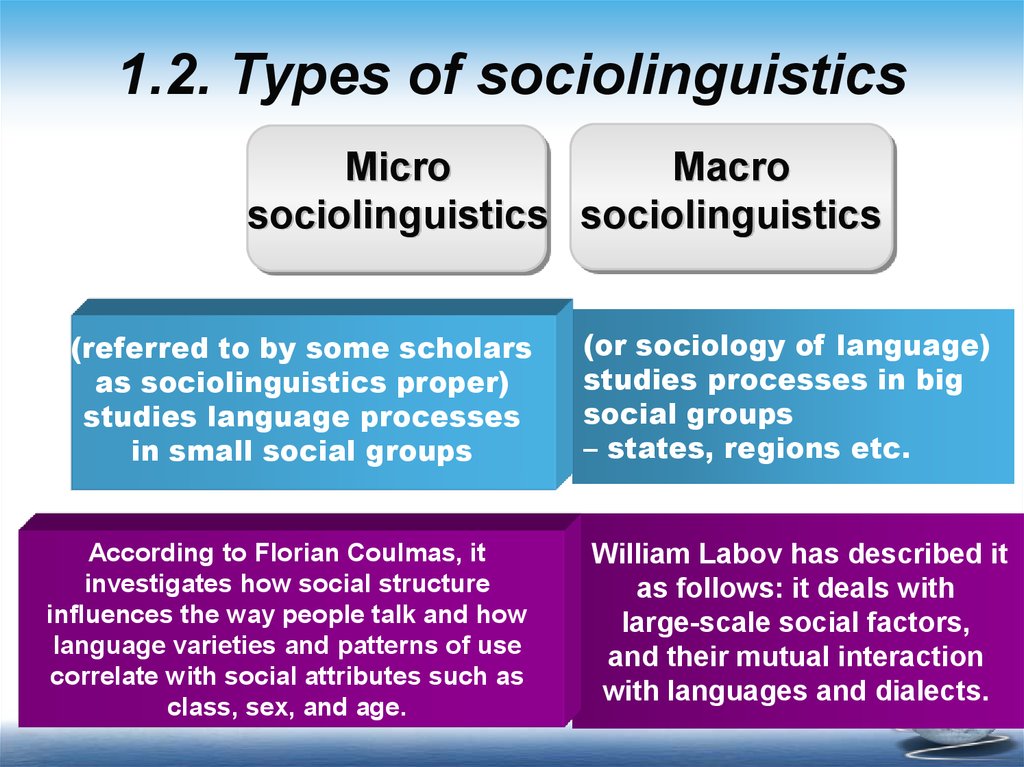

MicroMacro

sociolinguistics sociolinguistics

(referred to by some scholars

as sociolinguistics proper)

studies language processes

in small social groups

According to Florian Coulmas, it

investigates how social structure

influences the way people talk and how

language varieties and patterns of use

correlate with social attributes such as

class, sex, and age.

(or sociology of language)

studies processes in big

social groups

– states, regions etc.

William Labov has described it

as follows: it deals with

large-scale social factors,

and their mutual interaction

with languages and dialects.

11. 1.2. Types of sociolinguistics

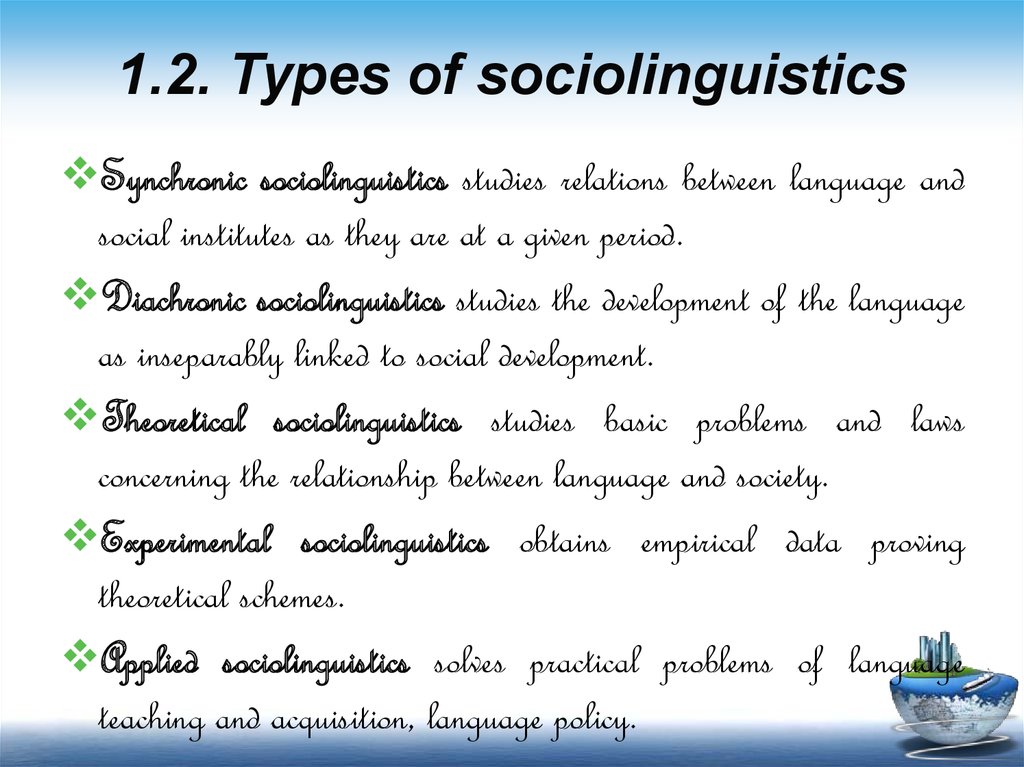

Synchronic sociolinguistics studies relations between language andsocial institutes as they are at a given period.

Diachronic sociolinguistics studies the development of the language

as inseparably linked to social development.

Theoretical sociolinguistics studies basic problems and laws

concerning the relationship between language and society.

Experimental sociolinguistics obtains empirical data proving

theoretical schemes.

Applied sociolinguistics solves practical problems of language

teaching and acquisition, language policy.

12. 1.3. Language variation

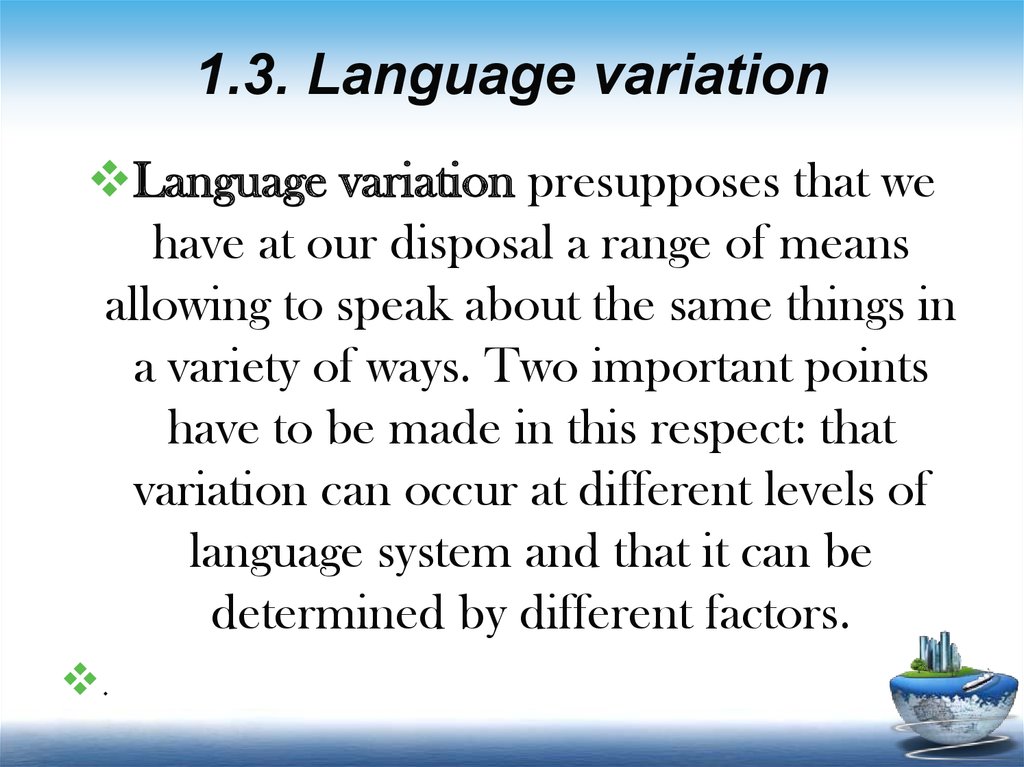

Language variation presupposes that wehave at our disposal a range of means

allowing to speak about the same things in

a variety of ways. Two important points

have to be made in this respect: that

variation can occur at different levels of

language system and that it can be

determined by different factors.

.

13. 1.3. Language variation

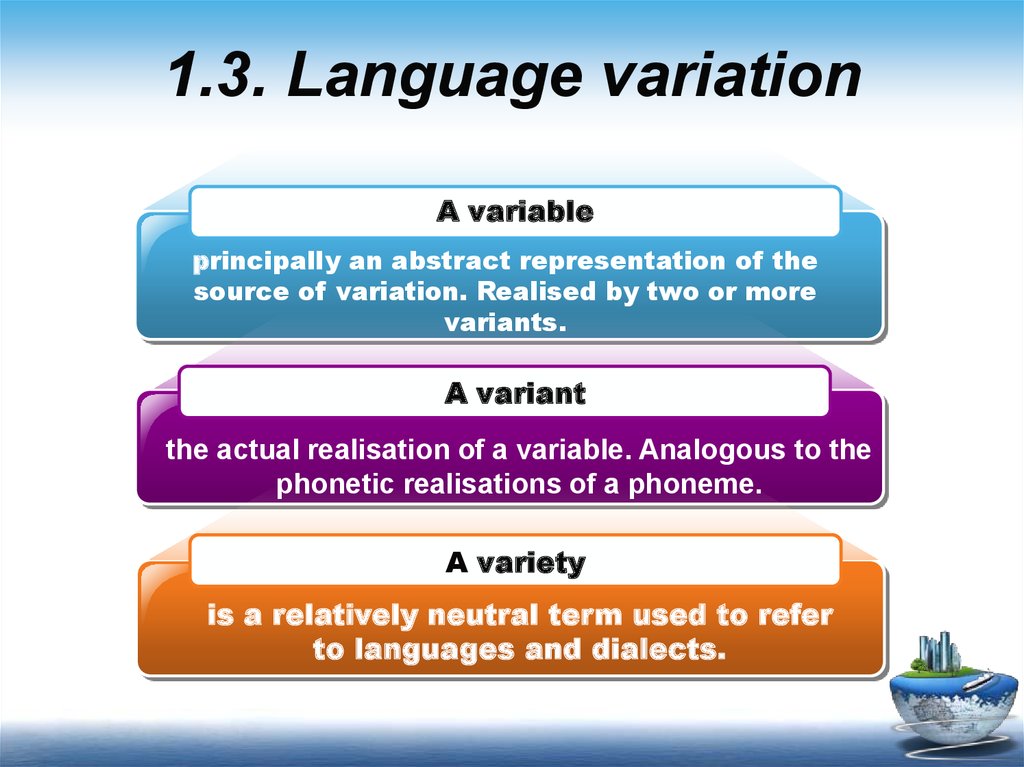

A variableprincipally an abstract representation of the

source of variation. Realised by two or more

variants.

A variant

the actual realisation of a variable. Analogous to the

phonetic realisations of a phoneme.

A variety

is a relatively neutral term used to refer

to languages and dialects.

14. 1.3. Language variation

The study of language in use with a focuson describing and explaining the

distribution of variables is called

variationist sociolinguistics. It is an

approach strongly associated with

quantitative methods in the tradition

established by William Labov.

15. 1.3.1. Variation on different levels of language system

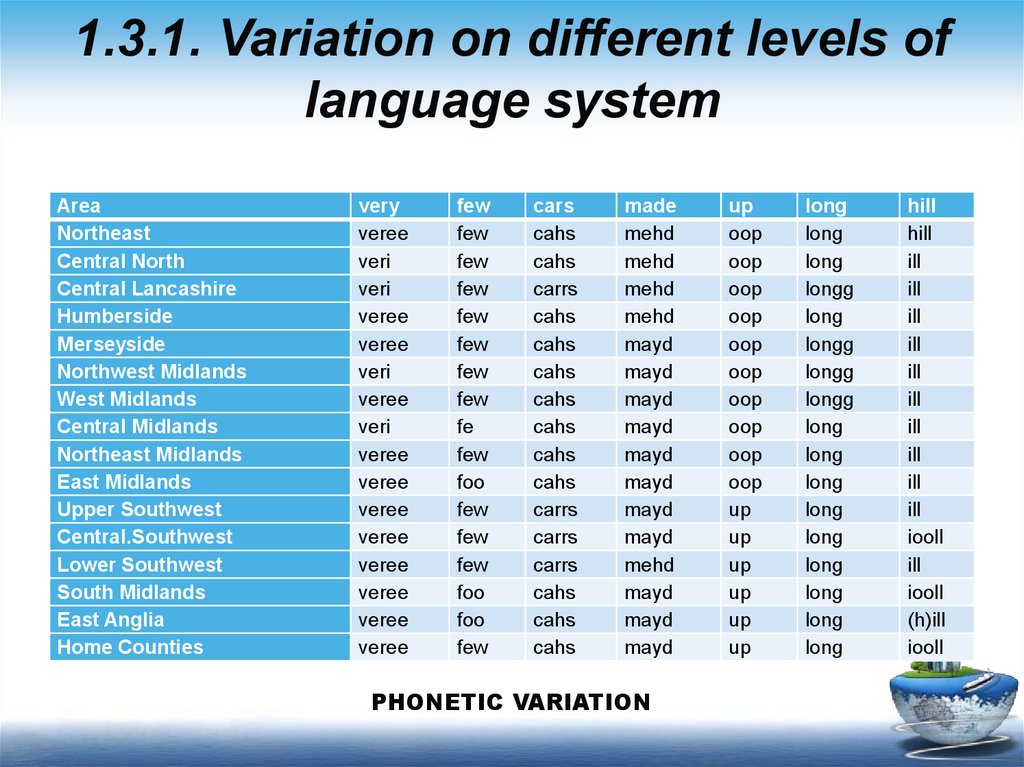

AreaNortheast

Central North

Central Lancashire

Humberside

Merseyside

Northwest Midlands

West Midlands

Central Midlands

Northeast Midlands

East Midlands

Upper Southwest

Central.Southwest

Lower Southwest

South Midlands

East Anglia

Home Counties

very

veree

veri

veri

veree

veree

veri

veree

veri

veree

veree

veree

veree

veree

veree

veree

veree

few

few

few

few

few

few

few

few

fe

few

foo

few

few

few

foo

foo

few

cars

cahs

cahs

carrs

cahs

cahs

cahs

cahs

cahs

cahs

cahs

carrs

carrs

carrs

cahs

cahs

cahs

made

mehd

mehd

mehd

mehd

mayd

mayd

mayd

mayd

mayd

mayd

mayd

mayd

mehd

mayd

mayd

mayd

PHONETIC VARIATION

up

oop

oop

oop

oop

oop

oop

oop

oop

oop

oop

up

up

up

up

up

up

long

long

long

longg

long

longg

longg

longg

long

long

long

long

long

long

long

long

long

hill

hill

ill

ill

ill

ill

ill

ill

ill

ill

ill

ill

iooll

ill

iooll

(h)ill

iooll

16. 1.3.1. Variation on different levels of language system

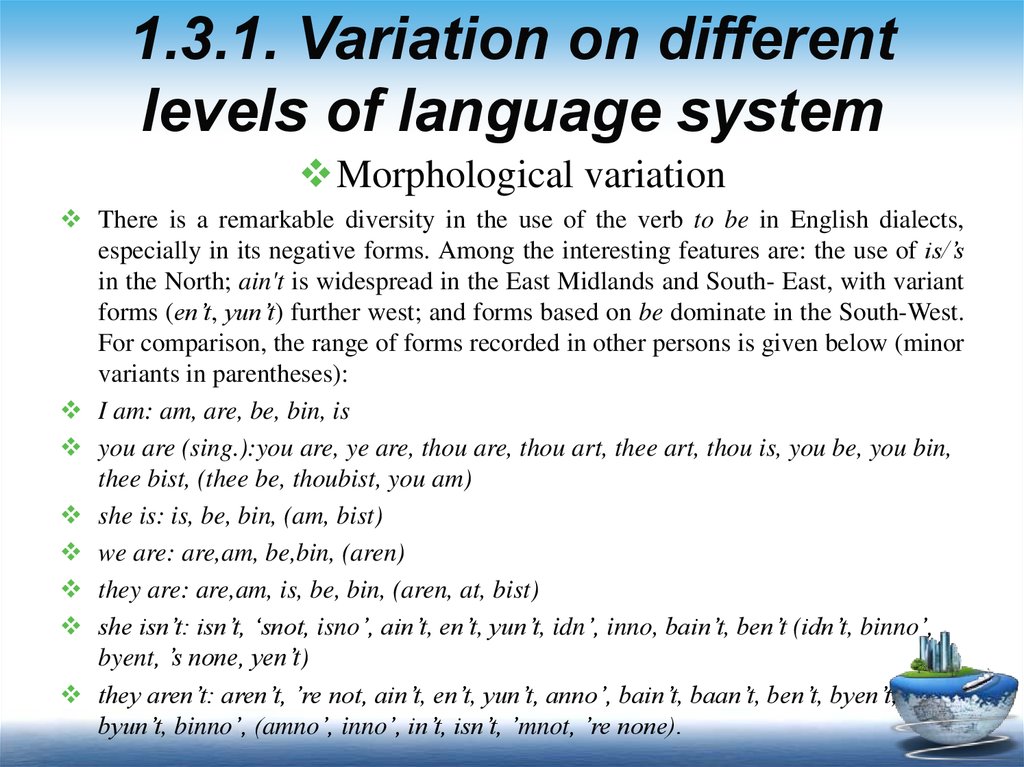

Morphological variationThere is a remarkable diversity in the use of the verb to be in English dialects,

especially in its negative forms. Among the interesting features are: the use of is/’s

in the North; ain't is widespread in the East Midlands and South- East, with variant

forms (en’t, yun’t) further west; and forms based on be dominate in the South-West.

For comparison, the range of forms recorded in other persons is given below (minor

variants in parentheses):

I am: am, are, be, bin, is

you are (sing.):you are, ye are, thou are, thou art, thee art, thou is, you be, you bin,

thee bist, (thee be, thoubist, you am)

she is: is, be, bin, (am, bist)

we are: are,am, be,bin, (aren)

they are: are,am, is, be, bin, (aren, at, bist)

she isn’t: isn’t, ‘snot, isno’, ain’t, en’t, yun’t, idn’, inno, bain’t, ben’t (idn’t, binno’,

byent, ’s none, yen’t)

they aren’t: aren’t, ’re not, ain’t, en’t, yun’t, anno’, bain’t, baan’t, ben’t, byen’t,

byun’t, binno’, (amno’, inno’, in’t, isn’t, ’mnot, ’re none).

17. 1.3.1. Variation on different levels of language system

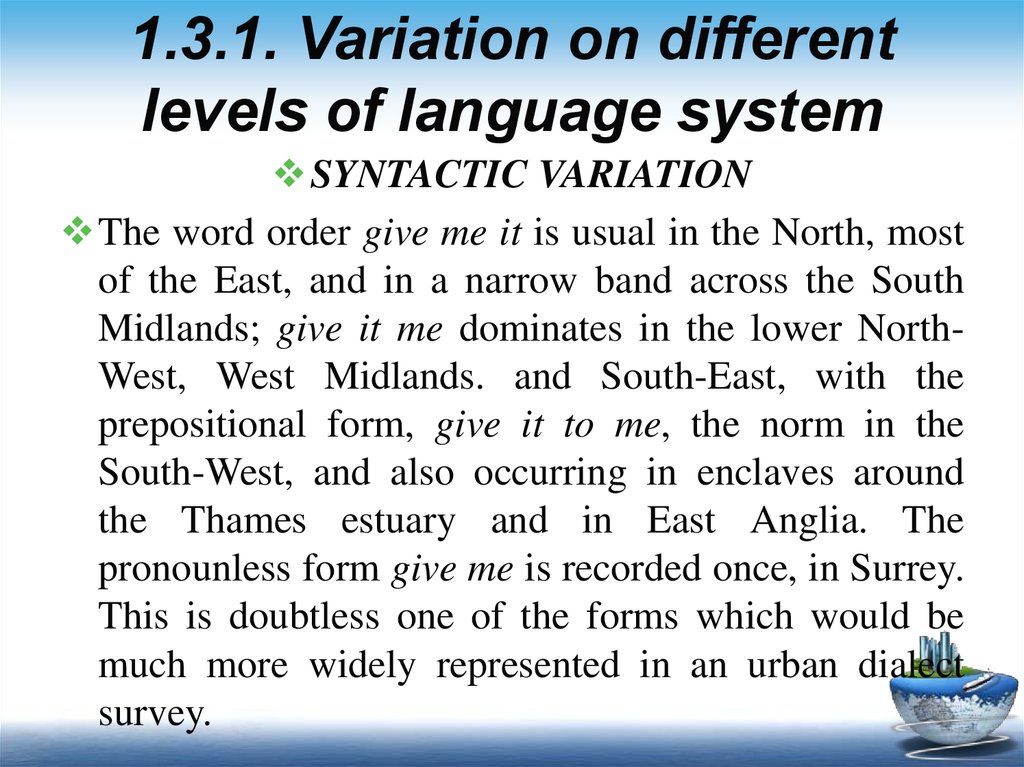

SYNTACTIC VARIATIONThe word order give me it is usual in the North, most

of the East, and in a narrow band across the South

Midlands; give it me dominates in the lower NorthWest, West Midlands. and South-East, with the

prepositional form, give it to me, the norm in the

South-West, and also occurring in enclaves around

the Thames estuary and in East Anglia. The

pronounless form give me is recorded once, in Surrey.

This is doubtless one of the forms which would be

much more widely represented in an urban dialect

survey.

18. 1.3.1. Variation on different levels of language system

LEXICAL VARIATIONThere are nine chief variants noted for threshold, for

example, and a further 35 alternatives. In the case of

headache, there is a fairly clear picture. The standard

form is used throughout most of the country, but in

the North and parts of East Anglia there is a

competing regional form, skullache. The variant form

head-wark is found in the far North, with a further

variant, headwarch, mainly in Southern Lancashire.

Northumberland opts for the more prosaic sore head,

with bad head used in adjacent localities to the south.

19. 1.3.2. Types of variation : temporal

Long term: English has changedthroughout the centuries, as can be seen

from such clearly distinguishable

linguistic periods as Old English, Middle

English, and Elizabethan English.

Language change is an inevitable and

continuing process, whose study is

chiefly carried on by philologists and

historical linguists.

20. 1.3.2. Types of variation: temporal

Short term: English changes within thehistory of a single person. This is most

noticeable while children are acquiring their

mother tongue, but it is also seen when people

learn a foreign language, develop their style as

adult speakers or writers. and, sometimes, find

that their linguistic abilities are lost or

seriously impaired through injury or disease.

Psycholinguists study language learning and

loss, as do several other professionals, notably

speech therapists and language teachers.

21. 1.3.2.2. Regional variation

Intranational regional varieties havebeen observed within English from its

earliest days, as seen in such labels as

‘Northern’, ‘London’ and ‘Scottish”.

International varieties are more recent

in origin, as seen in such labels as

‘American”, ‘Australian’ and ‘Indian’.

22. 1.3.2.2. Regional variation

A variety of language peculiar to somedistrict and having no normalized literary

form is known as dialect. However, in

cases when a regional variety is

characterized by statehood and possesses

a literary form (usually codified in

grammars and dictionaries) the term

variant is preferred.

23. 1.3.2.2. Regional variation

The term dialect is also to bedifferentiated from the term accent. A

regional accent refers to features of

pronunciation which convey

information about a person’s

geographical origin, e.g. bath [baө]

as opposed to [ba:ө]; hold [həuld]

and [əuld].

24. 1.3.2.2. Regional variation

A regional dialect refers to features of grammar andvocabulary which convey information about a

perons’s geographical origin. Compare, for instance,

They real good and They are really good; Is it ready

you are? and Are you ready?

Speakers who have a distinctive regional dialect will

have a distinctive regional accent but the reverse does

not necessarily follow. It is possible to have a

regional accent yet speak a dialect which conveys

nothing about geographical origin.

25. 1.3.2.3. Social variation

Their use of language is affected by their sex,age, ethnic group, and educational background.

English is being increasingly affected by all

these factors, because its developing role as a

world language is bringing it more and more

Into contact with new cultures and social

systems.

26. 1.3.2.4. Interspeaker variation and intraspeaker variation

interspeaker variation, i.e. that isvariation between individual speakers

The same words strut, price, night, tide

will be realized in two phonetic variants:

as [strΛt] [prais] [nait] [taid] in London

and as [strut] [preis] [neit] [teid] in the

Fens.

27. 1.3.2.4. Interspeaker variation and intraspeaker variation

the intraspeaker variation, i.e.variation within individual speakers.

The following situation can be an example of intraspeaker variation when

the same person will sometimes use one variant and sometimes the other

variant or even alternate in different sentences. A woman on Bequia (the

largest island in the Grenadines the native population being primarily a

mixture of people of African, Scottish and Carib Indian descent) was heard

calling to her grandson at dusk one evening. The exchange went like this:

Jed! Come here! [heə]

(silence from Jed)

Jed!! Come here!! [hiər]

28. variation according to use and variation according to user

User-related varietiesUser-related varieties are associated with

particular people and often places such as

Black English (English spoken by blacks,

especially by African-Americans in the US)

and Canadian English (English used in

Canada: either all such English or only the

standard form).

29. variation according to use and variation according to user

User-related varietiesWhen purely geographical aspect of variation is taken

into account the term dialect (for definition view

above) is applied. But when the social factor is

determining the term social dialect or sociolect is

employed. Social dialect embraces a number of

linguistic peculiarities typical of some social group –

professional, age, gender group or other. The term is a

blend (socio-+ dialect) that first appeared in the

1970s. The speakers of a sociolect usually share a

similar socioeconomic and / or educational

background.

30. variation according to use and variation according to user

Use-related varietiesUse-related varieties are associated with

function, such as legal English (the language

of courts, contracts, etc.) and literary English

(the typical usage of literary texts,

conversations, etc.). A variety of a language

used for a particular purpose or in a particular

social setting is called register.

31. variation according to use and variation according to user

Use-related varietiesFor example, an English speaker may adhere

more closely to prescribed grammar, pronounce

words ending in -ing with a velar nasal instead of

an alveolar nasal (e.g. walking, not walkin),

choose more formal words (e.g. father vs. dad,

child vs. kid, etc.), and refrain from using the

word ain’t when speaking in a formal setting, but

the same person could violate all of these

prescriptions in an informal setting.

32. 1.3.2.5. Personal variation

Code and code-switchingCode (language code) – languages, dialects, jargons

and stylistic varieties of the same language regarded

as a means of communication. All these – separate

languages or varieties of one language – in

sociolinguistics sometimes receive the name of

language formations. The sum total of codes and

subcodes used in a given language community that

complement each other functionally is called socialcommunicative system.

33. 1.3.2.5. Personal variation

Code and code-switchingDepending on the sphere of communication

the speaker switches from one language means

(one code) to another. This alteration between

varieties, or codes which takes place in

individual utterances, or even across sentences

or clause boundaries is called code-switching.

This phenomenon is identified as the reason of

for intraspeaker variation.

34.

LOGOAdd your company slogan

www.themegallery.com

Английский язык

Английский язык