Похожие презентации:

European Union Energy Policy

1.

European Union Energy Policy1

2.

European Union Energy Policy:Topic 1. Main and additional priorities of the European Union energy policy

Topic 2. Fuel and energy balance of the EU

Topic 3. Liberalization of EU gas and energy markets

Topic 4. EU energy diplomacy and external actions

Topic 5. The EU-Russia energy dialog

2

3.

Topic 1. Main and additional priorities of theEuropean Union energy policy

Introduction

Milestones of EU energy policy

Evolution of European energy policy

Legislation

3

4.

Energy is theirreplaceable part of

almost every aspect of

modern life from industry

to transportation, heating

and electricity, it is at the

heart of human

development and

economic growth.

4

5.

Energy is a fundamental factor in the construction ofEuropean Union project. The deep interaction and

cooperation among the founding members of the Union

crystallized around energy considerations.

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC)

Treaty and Euratom Treaty did not only establish the

roots of European Community but also ensured regular

supply of coal and coordination in nuclear energy.

5

6.

Nevertheless, despite energy’s importance in our dailylives, despite the fact that EU project “took off” with the

integration in economic domain and despite potential

beneficial effects of integration in terms of external energy

policy and action against climate change, European

Energy Policy displayed an unsuccessful example of

integration.

6

7.

The EU’s energydependence)

dependence

(import

Energy is the significant item on the agenda of

European decision makers

7

8.

The issue gets further complicated with the inclusion of worriesabout global warming, hazardous effects of certain energy types on

health and environmental damages due to energy production,

transportation and consumption, which overall require not only

secure access to energy but also access to clean and efficient energy.

8

9.

With these challenges on the background, until recently, climatechange and energy efficiency had started to outweigh the agenda of

internal and international efforts of the European Union concerning

the creation of an energy policy.

9

10.

Although some of the policies are still up to the individualchoices of each Member State in line with their national

preferences, global interdependence requires energy policy

to offer a European dimension.

10

11.

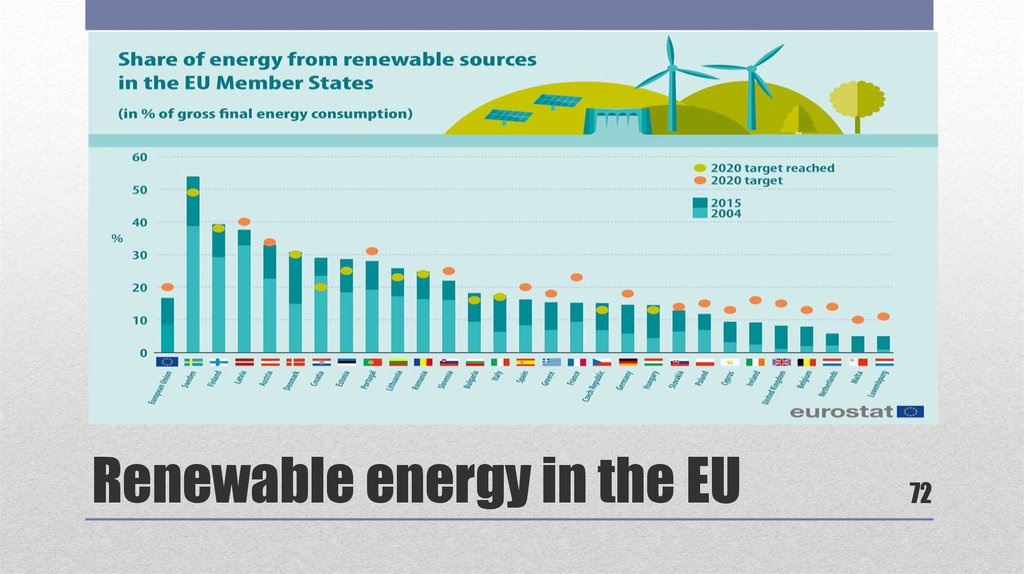

The milestones of EU energy policy:SUSTAINABILITY

COMPETITIVENESS

SECURITY OF SUPPLY

Maroš Šefčovič, Vice President

of the European Commission for

Energy Union

11

12.

Major European documents constituting these milestones ofEuropean energy policy:

Green Paper of 2006

The Commission's communication “An Energy Policy for

Europe” of 2007

12

13.

SUSTAINABILITY- linked to climate change

- 80% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emission in the Union is

caused by energy related activities

13

14.

COMPETITIVENESSaims at liberalization of energy market

at the opening of energy markets for the benefit of EU citizens in line

with latest energy technologies and investments in clean energy

production

14

15.

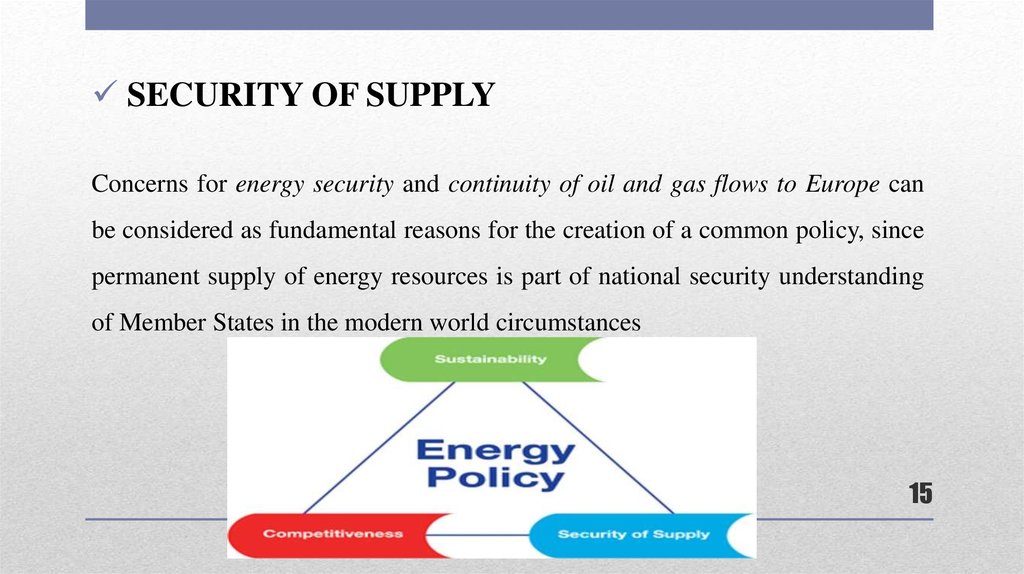

SECURITY OF SUPPLYConcerns for energy security and continuity of oil and gas flows to Europe can

be considered as fundamental reasons for the creation of a common policy, since

permanent supply of energy resources is part of national security understanding

of Member States in the modern world circumstances

15

16.

SECURITY OF SUPPLYIn 2030, it is expected that reliance on imports

of gas and oil will rise to 84% and 93% as

opposed to 57% and 82% in 2007, respectively.

16

17.

SECURITY OF SUPPLYWhen such a level of dependency is combined with

uncertainty about the willingness and capacity of oil

and gas exporters to invest more and increase

production to meet the increasing global demand,

threat of supply disruptions emerge as one of the

major challenges of the century.

17

18.

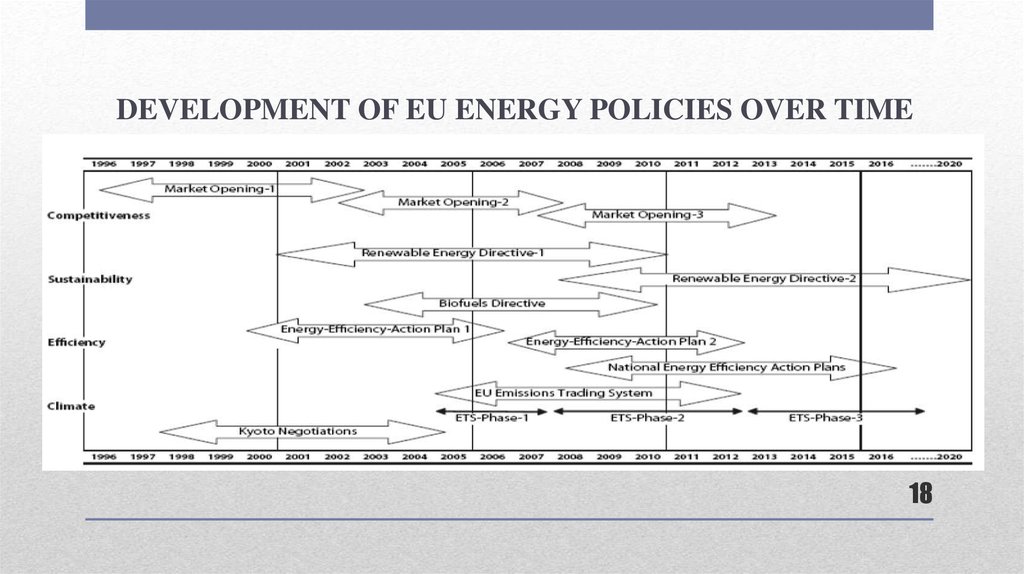

DEVELOPMENT OF EU ENERGY POLICIES OVER TIME18

19.

EVOLUTION OF EUROPEAN ENERGY UNIONIn the evolution of the EU itself, policies concerning energy

and energy security remained at the back plan. Left to

national discretion of Member States, decisions and

policies concerning energy security was initially excluded

from the EU level integration of European countries.

19

20.

European energy policy initiated as a need to be capable ofresponding to international energy supply crises:

the Suez crisis in 1956

the Six Day war between Egypt and Israel in 1967

Arab oil embargo in 1973

oil crisis following Iranian revolution in 1979

20

21.

International Energy Supply Crises two major concerns:1). political instability in producer countries and regional tensions

will lead to a disruption in oil supply

2). the threat that exporter countries can purposefully use oil and

natural gas as a weapon in their foreign relations

21

22.

THE RESPONSE TO SUCH CRISES:- Oil Stock Directive, 1968

- An amendment to the directive of 1968, accepted in 1972 72/425/EEC

- The establishment of International Energy Agency (IEA), 1973

- Two more directives - 73/238/EEC and 77/706/EEC

22

23.

The end of Cold Warthe end of ideological, political and economic divisions

between eastern and western Europe

in December 1991 political decision for EUROPEAN

ENERGY CHARTER was signed.

23

24.

EUROPEAN ENERGY CHARTER, 1991:competition

free transit

taxation

transparency

conditions on environment and sovereignty

24

25.

Between 1990 and 2000 – THREE Green Papers onENERGY =

BASELINES for a COMMON policy of the EU

25

26.

1994 – the Green Paper “For A European Union EnergyPolicy”

to establish an internal market

to increase the EU’s role in the energy sector

to harmonize national and community level of energy

policies

26

27.

1996 – the Green Paper “Energy for the Future:Renewable Sources of Energy”

incorporation of renewable energy sources into the future Community

strategy on energy

offered concrete strategies in the specific issue of renewable resources

mobilization of national and Community instruments for the development of

these resources in order to increase the percentage of renewable energy in the

EU’s energy mix

27

28.

!!! 2000 – the Green Paper “Towards a EuropeanStrategy for the Security of Energy Supply”

environmental concerns and repeated the interdependence between the

Member States which required a Community dimension in the strategies

dealing with energy related challenges

the Union’s increasing import dependence

focused on the security of supply

offered a detailed study concerning EU’s energy mixture

28

29.

2005 – the Green Paper “Green Paper on EnergyEfficiency or Doing More with Less”

The Commission suggested the establishment of energy efficiency Action Plan

which would be a multi-level initiative combining national, regional, community

and international levels. From buildings to tyres and clean vehicles, the paper

examined several measures especially in industrial and transportation sectors,

which could contribute to energy efficiency.

29

30.

Russia – Ukraine crises (2006)Member States understood the importance of

community level actions in the sphere of energy

policy

30

31.

2006 – the Green Paper “A European Strategy for Sustainable,Competitive and Secure Energy”

competitiveness and the creation of an internal market (common European

market)

diversification of energy mix

solidarity between member states

sustainable development as a response to climate change

innovation and technology for the increase of energy efficiency and diversity

through renewable resources

an integrated external policy

31

32.

“An Energy Policy for Europe” introduced“20/20 Package” (2007):

reducing GHG emission by 20%

improving energy efficiency by 20%

achieving a 20% share of renewable energy

a 10% share of biofuels by 2020

32

33.

2008 - An EU Energy Security and Solidarity ActionPlan

- infrastructure needs

- the diversification of energy supplies

- external energy relations

- oil and gas stocks and crisis response mechanisms

- energy efficiency

- making the best use of the EU’s indigenous energy resources

33

34. The Kyoto Protocol

(1997) is an international agreementwhich is intended to lower the greenhouse gas emissions of

the industrialized world by 2012. Ideally, the end result of

the Kyoto Protocol should be a reduction of these emissions

to below 1990 levels. The agreement also addresses the

issue of the developing world, which is rapidly

industrializing and therefore producing a large volume of

greenhouse gases.

The Kyoto Protocol

34

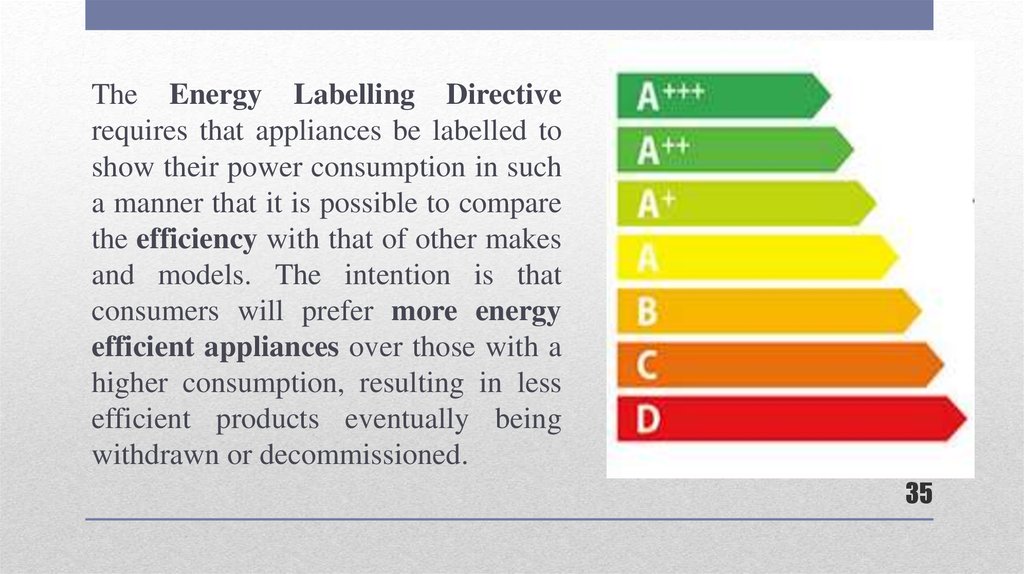

35.

The Energy Labelling Directiverequires that appliances be labelled to

show their power consumption in such

a manner that it is possible to compare

the efficiency with that of other makes

and models. The intention is that

consumers will prefer more energy

efficient appliances over those with a

higher consumption, resulting in less

efficient products eventually being

withdrawn or decommissioned.

35

36. EUROPEAN EMISSIONS STANDARDS

Each of the standardsEuro 1 to Euro 6 (the

latest) represent a total

amount of exhaust gas

emissions from a car. They

measure four main groups

of emission – carbon

monoxide, hydrocarbons,

nitrous

oxide

and

particulate matter.

EUROPEAN EMISSIONS STANDARDS

36

37. INTELLIGENT ENERGY EUROPE

Intelligent Energy – Europe(IEE) offered a helping hand to

organisations willing to improve

energy sustainability. Launched in

2003

by

the

European

Commission, the programme was

part of a broad push to create an

energy-intelligent future.

INTELLIGENT ENERGY EUROPE

37

38.

2011 - A Roadmap for Moving to a Competitive, LowCarbon Economy in 2050:- reducing emissions by 80% relative to what they were in

1990 by 2050 = this is what Europe needs to do in order to

make sure that global warming does not go beyond two

degrees centigrade (2°C is usually seen as the upper temperature limit to

avoid dangerous global warming).

38

39.

The latest decisions in this matter have come from the EuropeanCouncil of October 2014. That is to aim at reducing carbon

emissions by 40% by 2030.

Now, we have the following objectives:

1. for 2020, a reduction of 20% relative to 1990

2. we have an objective for 2050, a reduction by 80% and

3. we have an intermediate objective for 2030, a reduction

by 40%.

39

40.

Today the main goal is to establish ENERGY UNION!In 2015, the Framework Strategy for Energy Union is launched as

one of the European Commission's 10 Priorities.

40

41.

Topic 2. Fuel and energy balance ofthe EU

41

42.

The energy balance remains subject to thenational level, not common European

A plurality of energy models

42

43.

Oil:Malta, Cyprus,

Nuclear energy:

France, Sweden, Belgium

Coal:

Poland, the Czech Republic,

Bulgaria

Gas:

the UK, the Netherlands, Italy

43

44.

The energy available in theEuropean Union comes from

energy produced in the EU and

from energy imported from

third countries. In 2015, the

EU produced around 46 % of

its own energy, while 54 %

was imported.

44

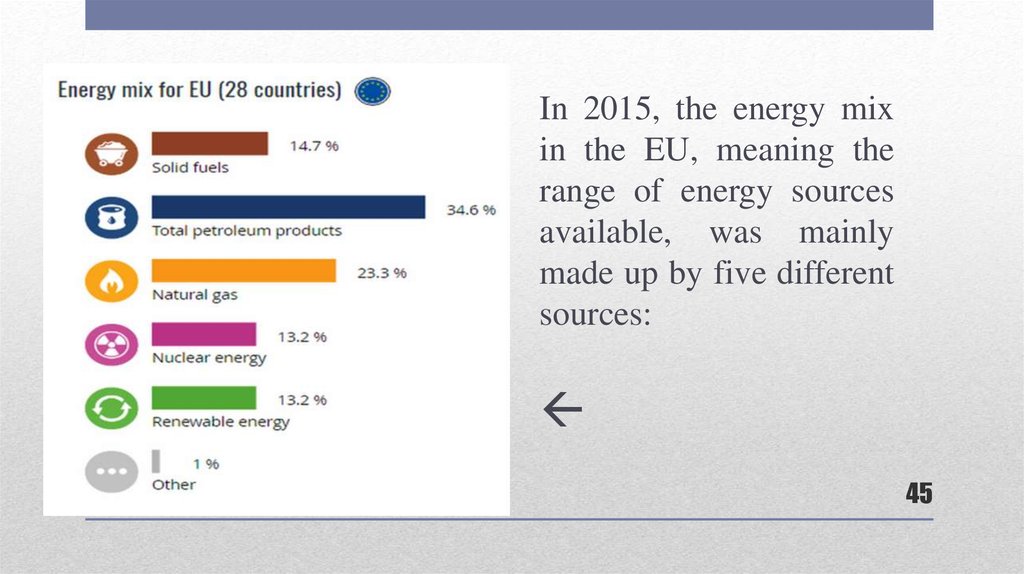

45.

In 2015, the energy mixin the EU, meaning the

range of energy sources

available, was mainly

made up by five different

sources:

45

46.

WHAT DOES THE EUPRODUCE?

Nuclear energy (29 % of total EU

energy production) was the largest

contributing source to energy

production in the EU in 2015.

Renewable energy (27 %) was the

second largest source, followed by

solid fuels (19 %), natural gas (14

%) and crude oil (10 %).

46

47.

However, the production of energy is very different from one MemberState to another. The significance of nuclear energy is particularly high

in France (83 % of total national energy production), Belgium (65 %)

and Slovakia (63 %). Renewable energy is the main source of energy

produced in a number of Member States, with over 90 % (of the

energy produced within the country) in Malta, Latvia, Portugal,

Cyprus and Lithuania. Solid fuels have the highest importance in

Poland (80 %), Estonia (76 %) and Greece (68 %), while natural gas is

the main source of energy produced in the Netherlands (82 %). Crude

oil is the major source of energy produced in Denmark (49 %) and the

United Kingdom (39 %).

47

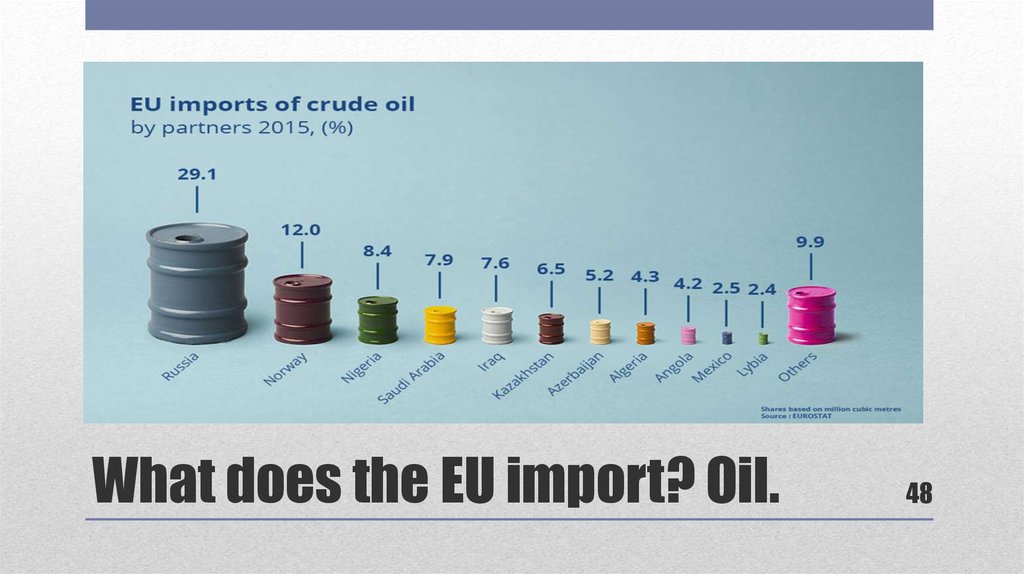

48. What does the EU import? Oil.

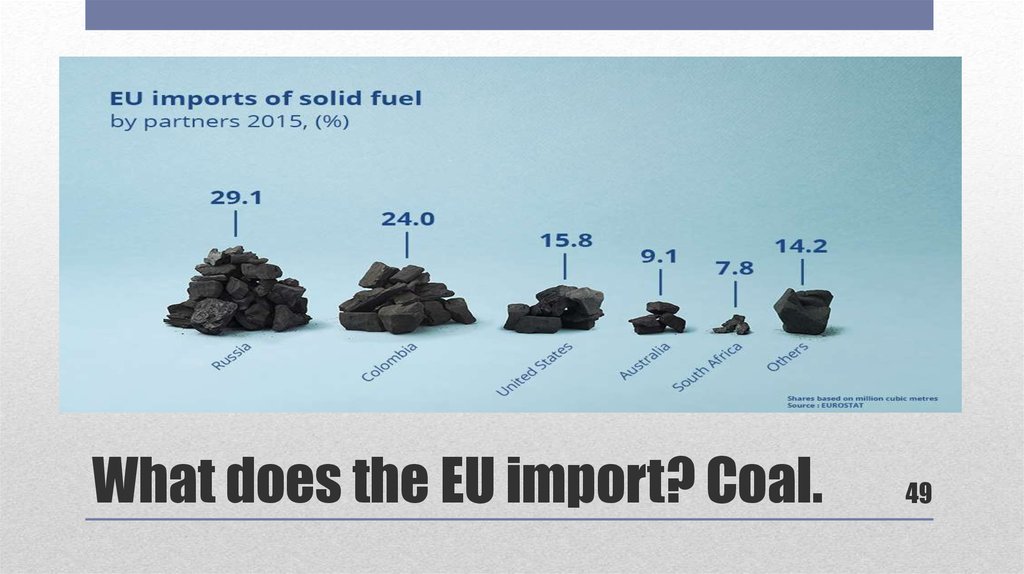

4849. What does the EU import? Coal.

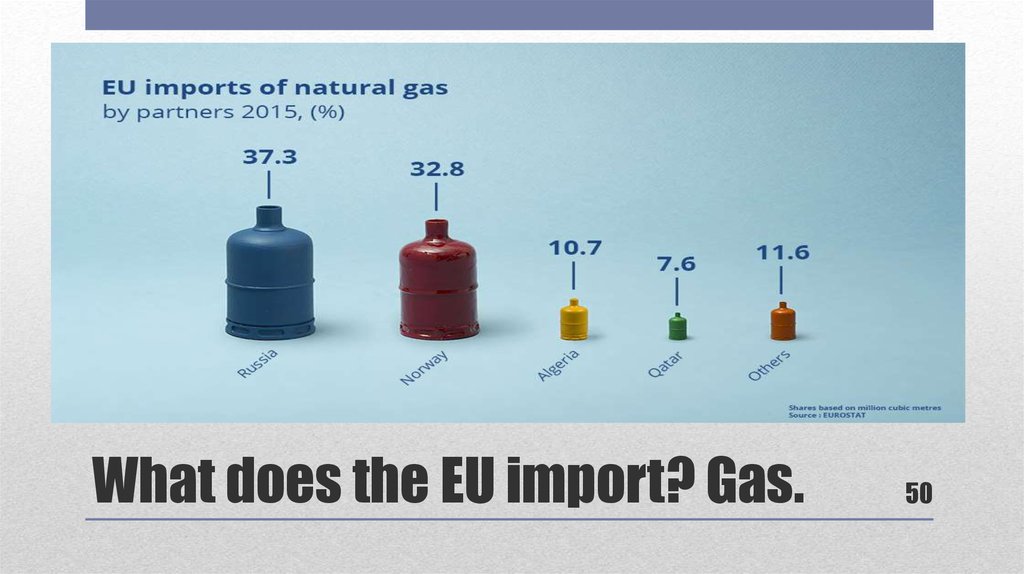

4950. What does the EU import? Gas.

5051. How dependent is the EU from energy produced outside the EU?

In the EU in 2015, the dependency rate was equal to 54 %, whichmeans that more than half of the EU’s energy needs were met by net

imports. This rate ranges from over 90 % in Malta, Luxembourg and

Cyprus, to below 20 % in Estonia, Denmark and Romania. The

dependency rate on energy imports has increased since 2000, when it

was just 47 %.

How dependent is the EU from

energy produced outside the EU?

51

52.

GAS. ADVANTAGES:- much lower emissions

- there is no need to maintain a reservoir for crude oil or

storage for coal

- the efficiency of the transformation is high

52

53.

The drawback of gas is the difficulty intransporting, high cost of transportation!

53

54.

The largest importers of Russian gas in the European Unionare Germany and Italy, accounting together for almost half

of the EU gas imports from Russia. Other larger Russian gas

importers (over 5 billion cubic meter per year) in the

European Union are France, Hungary, Czech Republic,

Poland, Austria and Slovakia.

54

55.

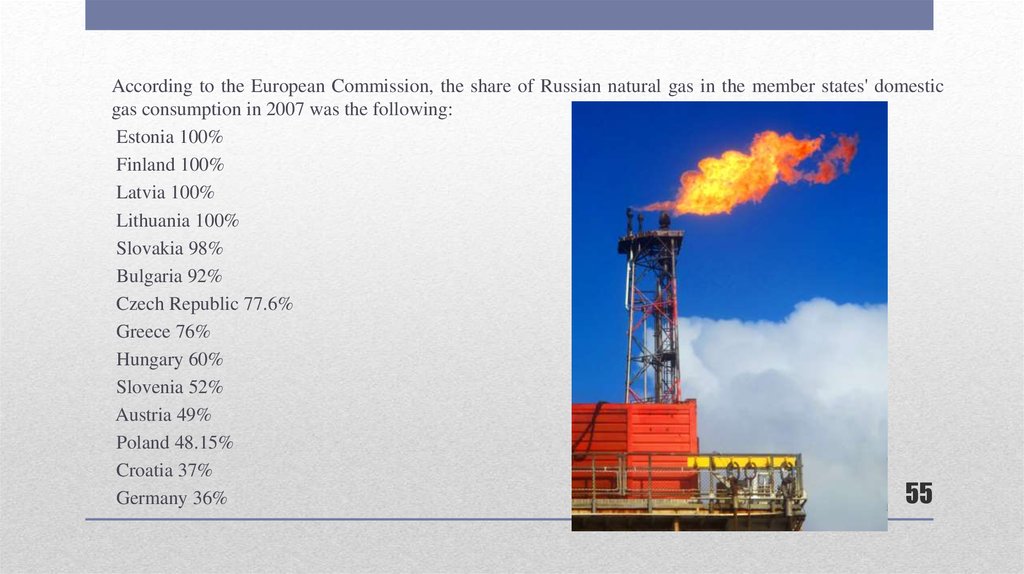

According to the European Commission, the share of Russian natural gas in the member states' domesticgas consumption in 2007 was the following:

Estonia 100%

Finland 100%

Latvia 100%

Lithuania 100%

Slovakia 98%

Bulgaria 92%

Czech Republic 77.6%

Greece 76%

Hungary 60%

Slovenia 52%

Austria 49%

Poland 48.15%

Croatia 37%

55

Germany 36%

56.

Oil. Advantages.Oil is a mix of hydrocarbons that are liquid under

atmospheric conditions. Therefore, the fact that they are

liquid allows for easier treatment of it, easier

transportation, easier containment in tanks, and it is one of

the greatest advantages of oil.

56

57.

Based on data from OPEC at the beginning of 2013the highest proved oil reserves oil deposits are in

Venezuela (20% of global reserves),

Saudi Arabia (18% of global reserves),

Canada (13% of global reserves), and

Iran (9%).

57

58.

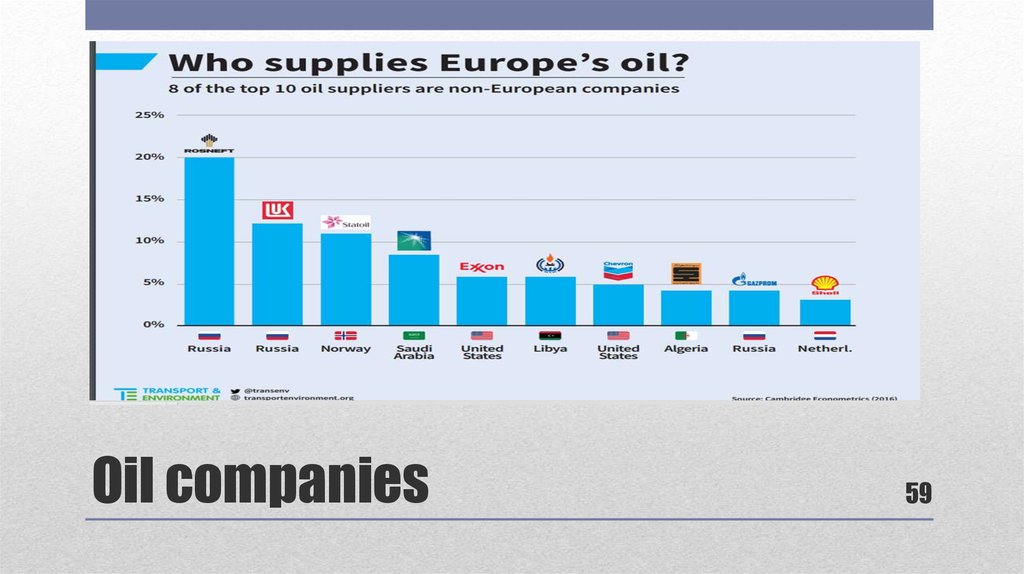

European dependence on oil imports has grown from76% in 2000 to over 88% in 2014. The EU spends

some €215 bn on oil imports, over 5 times as much as

gas imports (€40 bn). Russia is the biggest supplier:

dependence on Russia has grown from 22% in 2001

to 30% in 2015.

58

59. Oil companies

5960.

More than 40% of the oil was exported from MiddleEastern countries such as Algeria, Iraq, Libya, and

Angola, former Soviet states such as Azerbaijan and

Kazakhstan, and Nigeria and Angola in Africa. Russia

itself was the source of 30% of Europe’s crude imports.

Just two of the top 10 oil suppliers to the EU were European

– Shell and Statoil – whose combined crude market share

was 12%. In total 88% of Europe’s crude was imported.

60

61. Coal

Countries exporting coal to EU are Russia, Colombia andAustralia with shares of 32.5 %, 23.2 % and 15.8 %

respectively 30.4 %, 23.7 % and 11.5 % in 2015. Imports

shares from USA and South Africa slightly decreased

respectively 14.3 % versus 17.4 % and 6.1 % versus 8.1 %.

Coal

61

62. Coal

• Coal, as the largest artificial contributor to carbon dioxide emissions, has beenattacked for its detrimental effects on health. Coal has been linked to acid rain,

smog pollution, respiratory diseases, mining accidents, reduced agricultural

yields and climate change.

• Proponents of coal downplay these claims and instead advocate the low cost

of using coal for energy. Many European countries, such as Italy, have turned

to coal as natural gas and oil prices rose.

Coal

62

63. Nuclear energy

potentially very cheapthe lowest carbon emissions

Nuclear power plants generate almost 30% of the electricity

produced in the EU. There are 130 nuclear reactors in operation in 14

EU countries. Each EU country decides alone whether to include

nuclear power in its energy mix or not.

Nuclear energy

63

64. Nuclear safety

The EU promotes the highest safety standards for alltypes of civilian nuclear activity, including power

generation, research, and medical use. In response to

the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident, a series of

stress tests were carried out in 2011 and 2012 to

measure the ability of EU nuclear installations to

withstand natural disasters.

Nuclear safety

64

65. Radioactive waste and decommissioning

Radioactive waste results from nuclear activities such as electricitygeneration, medicine, and research. The EU's Directive for the

Management of Radioactive Waste and Spent Fuel sets out rules for

safely disposing of used radioactive materials.

The shutting down and decommissioning of a nuclear power plant at

the end of its lifecycle is a long and expensive process. The 'Waste

Directive' also requires the creation of EU member states plans for

financing the safe disposal of radioactive waste during

decommissioning.

Radioactive waste and

decommissioning

65

66. Nuclear energy

France is the one country that has the most of its electricity fromnuclear power. It has a dependency of approximately 75% of total

electricity produced from nuclear power.

But not many people realize that even Belgium, Slovakia and

Hungary have levels of dependency on nuclear energy that are of

the order of 50%. And then we have Sweden that has a dependency

of above 40%.

Nuclear energy

66

67. Nuclear energy

Russian nuclear reactors in the EU are in Bulgaria (2),Czech Republic (6), Finland (2), Hungary (4) and Slovakia

(4, with two more being built). Hungary has an agreement

for two more to be built, and Finland is planning one with

Russian equity.

Nuclear energy

67

68. Renewable energy

The use of renewable energy has many potential benefits,including a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, the

diversification of energy supplies and a reduced

dependency on fossil fuel markets (in particular, oil and

gas).

Renewable energy

68

69. Renewable energy

The share of renewable energy in energyconsumption increased continuously between 2004

and 2015, from 8.5 % to 16.7 %, approaching the

Europe 2020 target of 20 % by 2020.

Renewable energy

69

70. Renewable energy

The share of renewable energy in the Member States washighest in Sweden (53.9 % of energy consumption)

followed by Finland (39.3 %) and Latvia (37.6 %). This

share was lowest in Luxembourg and Malta (both 5.0 %),

the Netherlands (5.8 %) and Belgium (7.9 %).

Renewable energy

70

71. Renewable energy

This positive development has been prompted by the legallybinding (обладающий обязательным характером) targets

for increasing the share of energy from renewable sources

enacted by Directive 2009/28/EC on the promotion of the

use of energy from renewable sources.

Renewable energy

71

72. Renewable energy in the EU

7273.

Topic 3. Liberalization of EU gasand energy markets

73

74. Liberalization Process: Legislation

The liberalization process of the natural gas market is a result of thethree Directives handed down by the European Commission in 1998

(98/30/EC), 2003 (2003/55/EC), and most recently in 2009

(2009/79/EC).

The Directives aimed to create an internal market for natural gas,

which would theoretically lower prices and increase energy

security through introducing more competition.

Liberalization Process: Legislation

74

75. Liberalization Process

In all of the Directives, there are several components thatcomprise the bulk of the liberalization process, and they are:

third party access, unbundling, contracts, and a regulatory

authority.

The EU emphasized these because they were seen as the

primary barriers to a competitive market.

Liberalization Process

75

76. Liberalization Process

The first portion of the liberalization process requires statesto grant third parties to the gas transmission system and the

gas storage system. Third-party access (TPA) is when a firm

that does not own the actual pipeline or storage facility must

have access to operate it, assuming certain conditions are

met by both the owner and operator of the system.

Liberalization Process

76

77. Liberalization Process

The 2003 Directive extended third-party access to gasstorage facilities in addition to the transmission systems.

Since natural gas can be stored, storage facilities play an

important role; firms that are not a part of the production

process can buy gas, store it, and then eventually sell it to

customers at a later date, bringing another actor into the

transaction between producing country and consuming

country.

Liberalization Process

77

78. Liberalization . Unbundling.

The next aspect of the Directives is the concept of unbundling.At its core, unbundling is separating vertically integrated companies,

forcing firms either to be only involved in either production or

transmission or distribution.

Emphasizing unbundling is supposed to facilitate the entry of more

actors in the market, thus making it more competitive.

Liberalization . Unbundling.

78

79. Liberalization. Interruptible contracts

The EU Directives is encouraging shorter and interruptible contracts,starting in 2003.

The 2009 Directive went further and told Member States explicitly

that they “should encourage the development of interruptible supply

contracts”.

Liberalization. Interruptible

contracts

79

80. Liberalization. Regulatory authority

The last major area of focus in liberalization reform is the creation ofa regulatory authority.

Chapter IX of Directive 2009/72/EC requires each Member State to

designate a single National Regulatory Authority (NRA). Member

States may designate other regulatory authorities for regions within

the Member State, but there must be a senior representative at

national level. Member States must ensure that the NRA is able to

carry out its regulatory activities independently from government

and from any other public or private entity.

Liberalization. Regulatory authority

80

81. Liberalization of EU gas market

The Third Energy Package consists of two Directives and three Regulations:Directive 2009/72/EC concerning common rules for the internal market in

electricity and repealing Directive 2003/54/EC

Directive 2009/73/EC concerning common rules for the internal market in

natural gas and repealing Directive 2003/55/EC

Regulation (EC) No 714/2009 on conditions for access to the network for

cross-border exchanges in electricity and repealing Regulation (EC) No

1228/2003

Regulation (EC) No 715/2009 on conditions for access to the natural gas

transmission networks and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1775/2005

Regulation (EC) No 713/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council

of 13 July 2009 establishing an Agency for the Cooperation of Energy

Regulators

Liberalization of EU gas market

81

82.

Topic 4. EU energy diplomacy andexternal actions

82

83.

Internal and external energy policiescannot be separated from each other

due to their complimentary nature.

High import dependency trends

highlight that the Union is in urgent

need for a common approach to

external energy policy which would

shape relations and partnerships of

Europe with global energy actors

being consumers, producers, transit

countries or major companies

83

84.

Concerning its ambitious goals about sustainability, renewableresources and fight against climate change the EU is aware that

the efforts of its members have to be combined with the

cooperation of other consumer states, developing countries or

producer states in order to obtain effective outcomes.

84

85.

In the study of external energy policy of Europe it is possible to classify it underthree major strategies:

1). the extension of internal energy policies and internal energy market to the

international arena, which is also based on the integration of energy into

broader external relations, which would eventually end up with a panEuropean Energy Community

2). dialogue with third parties

3). diversification is the last major strategy as it basically indicates the

strengthening of existing infrastructures and construction of new ones for

alternative energy supplies

85

86.

Pan-European Energy Community is “common regulatoryspace” in other words “common trade, transit and environment

rules” between the Member States and EU neighboring

countries.

The extension of EU’s own internal market to its neighbors and

partners is the strategy that the policy makers are trying to

pursue with the argument that only well-functioning

international market can assure affordable oil and gas supplies

and encourage new investments.

86

87.

European Neighbourhood PolicyIn the European Neighbourhood Policy Strategy Paper, the

Commission indicates that “Enhancing our strategic energy

partnership with neighbouring countries is a major element of

the European Neighbourhood Policy”. Hence, in order to

increase energy cooperation with EU neighbouring countries

which are key players in the energy supply security as suppliers

(such as Southern Caucasus countries, Algeria, Egypt and Libya)

or as transit countries (Ukraine, Belarus, Morocco and Tunisia),

ENP is a way to institutionalize external energy dialogues.

87

88.

EU energy goals require efficient usage of financialinstruments through European Investment Bank (EIB),

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

(EBRD), Neighbourhood Investment Fund.

88

89.

The Kyoto Protocol (1997)The Kyoto Protocol is an international agreement which

is intended to lower the greenhouse gas emissions of the

industrialized world by 2012. Ideally, the end result of

the Kyoto Protocol should be a reduction of these

emissions to below 1990 levels. The agreement also

addresses the issue of the developing world, which is

rapidly industrializing and therefore producing a large

volume of greenhouse gases.

89

90.

NORWAYNorway is the second major natural gas and oil supplier to

the European Union.

June 1971 is the beginning of the production in the

Norwegian continental shelf, and since then twenty billion

barrels of oil have been extracted from the area.

90

91. Norway

differs from other energy suppliers to the Unionbecause it is a member of European Economic Area. The

legislation concerning EU’s internal energy market and

related policy arrangements about competition law,

environmental regulations, consumer rights and new

technologies are already implemented by Norway.

Norway

91

92. Norway

Not only the EU needs Norway as a reliable oil and gassupplier but also Norway needs the EU since EU Members

namely, Germany, United Kingdom, France, Belgium, the

Netherlands account for the majority of Norway’s natural

gas exports in 2008.

Norway

92

93. Norway

and the EU act together to further develop theirpartnership. The Commission as well emphasizes the

potential of Norway in the maximization of Europe’s

energy security and suggests the promotion of common

exploration projects in the Norwegian continental shelf and

the promotion of alternative energy production such as

offshore wind in the North Sea

Norway

93

94. Africa

Concerning EU’s dialogue with Africa, energy isincorporated within the development and governance

issues. Poverty reduction projects and improvement of

energy delivery systems to rural areas attracts the Union’s

interests and to this end, initiatives and aid funds are

offered.

The example is the EU Initiative for Poverty Eradication

and Sustainable Development launched in 2002

Africa

94

95. Africa

In the region, the EU policy makers associate the Union’s energyinterests with broader political and security considerations. Still, due

to high instability in the region, EU’s efforts remain insufficient in

the implementation of development projects. To illustrate despite

being the fourth major natural gas supplier of the EU, Nigeria

remained as the Africa’s “most under-funded state” since corruption

and lack of transparency hindered investment efforts. Instead of rule

of law, oil contracts and government positions were used as political

means to “buy off” militants.

Africa

95

96. Africa

Nevertheless, Africa, more specifically North Africa has asignificant potential not only in hydrocarbons but also in renewable

energy sources. Despite the inconvenient conditions for

investments, secure extraction and transportation of resources,

Algeria, Egypt, Libya and Nigeria outstand as important suppliers

after Russia and Norway, especially in natural gas imports.

Africa

96

97. Middle East

is the world’s important energy producing region andworld’s richest proven oil and natural gas reserves belong to the

region. Seeking ways to guarantee its energy security, EU aims to

institutionalize its energy relations with the region, especially with

the Persian Gulf countries some such as Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi

Arabia and United Arab Emirates being member of Organization of

Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Middle East

97

98. Middle East

Despite the Union’s intense energy dialogues with Russiaor Caspian region, Middle East remains as a “critical player

in energy policy” especially due to its rich resources,

geographical advantages and its potential to stabilize world

market prices in line with its oil supply capacity.

Middle East

98

99. Middle East

Concerning the region, EU’s effort to achieve internationalcooperation in energy is not limited to the dialogue with the Gulf

Cooperation Council. The Euro-Mediterranean Energy Partnership

(Euromed) is another platform for EU to pursue its goals of energy

security and sustainability. The partnership consists of EU Member

States and Mediterranean and Middle Eastern partners (Algeria,

Egypt, Israel, Jordon, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestinian Authority,

Syria, Tunisia and Turkey) and its origins date back to 1995 the

Euro-Mediterranean Conference of Ministers of Foreign Affairs.

Middle East

99

100. Caspian Region

Caspian region refers to five Caspian littoral states namely,Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Russia.

The critical point about the region is the legal status of the Caspian

Sea. With the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the determination

of official sea boundary between the states emerged as a question.

No agreement has been reached between the littoral states

concerning the debate on whether the subject matter is a lake or sea.

Caspian Region

100

101. Caspian Region

This identification is necessary because, if the Caspian is a sea, inline with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea,

bordering countries will be able to claim 12 miles from the shore as

their territorial waters and beyond that a 200-mile exclusive

economic zone and this will cause an uneven distribution of oil and

natural gas resources in the basin.

Caspian Region

101

102. Caspian Region

Apart from the legal status of the potential reserves, the factthat Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan are

landlocked states, the construction of oil and natural gas

transit routes create a further challenge for the region.

Caspian Region

102

103. Caspian Region

The institutionalization of relations with the CaspianRegion countries:

- the INOGATE, Interstate Oil and Gas Transport to

Europe program

- Baku Initiative

- the Black Sea initiative

Caspian Region

103

104. Caspian Region

Energy outstands as the main item among the imports from theregion.

Nevertheless, mineral fuels imported from the region represent very

small shares among total imports of EU from the world market.

Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Iran correspond to only

2.3%, 0.3%, 3.4 % and 2.8% of EU’s total imports, respectively.

Compared with the region’s oil and gas reserves, these results

indicate that the potential of these countries is not being efficiently

used, yet.

Caspian Region

104

105. Southern Gas Corridor

The Southern Gas Corridor is an initiative of the EuropeanCommission for the natural gas supply from Caspian and Middle

Eastern regions to Europe. The goals of the Southern Gas Corridor

are to reduce Europe's dependency on Russian gas and add diverse

sources of energy supply. The route from Azerbaijan to Europe

consists of the South Caucasus Pipeline, the Trans-Anatolian

Pipeline, and the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (under construction). The

total investment of this route is estimated US$45 billion. The main

supply source would be the Shah Deniz gas field, located in the

Caspian Sea.

Southern Gas Corridor

105

106.

Topic 4. The EU-Russia energydialog

106

107.

Russia is the main exporter of energy resources tothe European Union. This distinguishes Russia

from other energy partners and urges the Union to

develop a special partnership with it, as part of EU

energy security strategy.

107

108.

When Russia’s internal energy sector is examined the mostoutstanding feature is state’s control over resources. Russia’s oil

exports are under the jurisdiction of Transneft which is Russia’s

state owned pipeline monopoly.

Three oil pipelines:

Druzhba Pipeline

the Baltic Pipeline System (BPS)

Adria Pipeline

108

109.

Concerning the natural gas sector, again a state run monopoly,Gazprom accounts for almost 90% of Russian natural gas

production and controls the country’s gas exports.

Main gas pipelines:

1. NORD STREAM

Capacity: 55 billion cubic meters per year. Partners: Gazprom, Wintershall,

E.ON, Gasunie, Engie.

The Nord Stream pipeline became operational in 2011. First proposed in

1997, disputes between Kiev and Moscow in 2006 and 2009 prompted

Russia to stop natural gas flows through Ukraine, depriving Europe of

natural gas and accelerating Nord Stream construction. The pipeline

enables Russia to deliver energy directly to Germany and parts of Central

Europe.

109

110.

2. NORTHERN LIGHTS AND YAMAL EUROPECapacity: 84 bilion cubic meters per year. Partners: Gazprom, Beltrangaz,

PGNiG.

The Northern Lights and Yamal-Europe pipelines are two major systems

that deliver Russian gas to Eastern Europe.

3. SOYUZ

Capacity: 26 billion cubic meters per year. Partners: Gazprom,

Ukrtransgaz.

The Soyuz and Brotherhood pipelines are Gazprom’s major export routes

for delivering gas to Europe through Ukraine. They have a total capacity of

over 150 billion cubic meters. In an effort to avoid using Ukraine as a

transit state, Gazprom is seeking alternative routes from 2019 onward.

110

111.

4. BLUE STREAMCapacity: 16 bilion cubic meters per year (expanding to 19 bcm). Partners:

Gazprom, BOTAS, Eni.

One of two major pipeline systems that Gazprom uses to deliver natural gas

to Turkey. Gazprom can deliver about 16 bcm to Turkey via Ukraine, and

another 16 bcm directly to Turkey via Blue Stream. At the moment, neither

pipeline alone has the capacity to meet Turkey’s energy demands. In 2014,

Turkey and Russia agreed to expand the capacity of Blue Stream by 3 bcm.

5. RUSSIAN GAS-WEST PIPELINE

Capacity: 16 billion cubic meters per year. Partners: BOTAS, Transgaz,

Bulgartransgaz.

The Russian Gas-West pipelines deliver gas to Turkey through Ukraine,

Romania and Bulgaria. In the future Turkish demand will exceed both the

existing pipelines’ capacity and a third will be needed.

111

112.

6. NORD STREAM 2Capacity: 55 billion cubic meters per year. Partners: Gazprom, Shell, OMV,

E.ON.

Gazprom signed a memorandum of understanding with Shell, OMV, and

E.ON at the 2015 St Petersburg International Economic Forum to build the

Nord Stream-2 pipeline. As proposed, Nord Stream-2 would be the same

size as the original pipeline and go operational in late 2019. The pipeline

will increase capacity over time to balance out reduced North Sea

production.

7. TURKISH STREAM

Capacity: 63 billion cubic meters per year. Partners: BOTAS, Gazprom.

The pipeline is designed to provide an alternative route to deliver natural

gas into southern Europe, bypassing Ukraine.

112

113.

8. EASTRING PIPELINECapacity: 20 billion to 40 billion cubic meters per year. Partners: Eustream,

Transgaz, Bulgartransgaz.

Eastring would connect infrastructure in Slovakia to Romania and Bulgaria.

Slovakia has taken the lead on the project and even suggested connecting to

TurkStream. Bratislava wants to be part of Gazprom’s plans to diversify transit

options away from Ukraine because Slovakia is the critical link between pipelines

in Ukraine and central Europe.

9. SOUTH STREAM

Capacity: 63 billion cubic meters per year. Partners: Gazprom, Eni, others.

South Stream was a pipeline system that would have sent gas from Russia to

Bulgaria across the Black Sea and then onward through Serbia into Central

Europe. Gazprom canceled the project in December 2013 and is pursuing the

TurkStream pipeline project instead, hoping to achieve the same strategic goal of

bypassing Ukraine. The European Commission opposed South Stream and

113

contributed to Gazprom’s cancellation of the project.

114.

The institutionalization of EU-Russia relationship concerningenergy can be identified by three main legal grounds: European

Energy Charter, EU-Russia Energy Dialogue and “Four

Common Spaces”.

However, the initial move which

transformed this relationship into a “partnership” is the ten year

bilateral treaty Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA)

which came into force in 1997. Article 65 of the Agreement

directly addresses energy and offers cooperation in issues such

as supply security, infrastructure, energy efficiency and

formulation of energy policy.

114

115.

Due to Russia’s non-ratification of Energy Charter Treaty, therelationship between EU and Russia has to be conducted in

another platform. EU-Russia Summits compensated this

deficiency and helped to increase the coordination between the

parties.

In May 2003, EU and Russia decided to set a framework for

cooperation. As the name suggested the new framework “Four

Common Spaces” focused on four main areas: economy, foreign

and security policy, justice and home affairs, and culture,

information and education”, energy being included under the

economy section.

115

116.

Thank you forattention!

116

Экология

Экология