Похожие презентации:

Financial planning

1. MBA Sport Management

Financial Planning + Time value of moneyHubert János Kiss

2. 2. dia

Financial PlanningPlan of the day

Today we will see financial planning and the time value of money.

First we will speak in general about the process of financial planning.

Then we will go through an example in detail to see how the planning can be

done. Afterwards, we will do financial planning for a sport club (Manchester

United) based on real numbers. Thus, you can see that financial planning can

be applied really and that after the class you will be able to make such plans.

Next, we will speak about the importance of external finance needs and

sustainable rate of growth.

An important part of financial planning is to ensure that the daily operations

of the company can be financed. Working capital management and cash

budgeting deal with this issue.

Then we change topic and will study the time value of money, one of the

pillars of finance.

The material that we cover builds strongly – as always - on

• chapter 3 in Bodie – Merton - Cleeton, D. L. (2009). Financial Economics.

Pearson/Prentice Hall

• the chapter about working capital in Brealey – Myers: Principles of Corporate

Finance.

3. 3. dia

Financial PlanningFinancial Planning

The class on financial statements served to understand how a firm is working

from a financial point of view.

If you are a manager, then you should understand how your firm works, but

you should manage it as well. That means that you should set targets and see

how those targets can be achieved and the appropriate financial background

should be secured. Financial planning helps in this endeavour.

4. 4. dia

Financial PlanningThe Financial Planning Process

Financial planning is a dynamic process that follows a cycle of making plans,

implementing them, and revising them in the light of actual results.

The starting point is the strategic plan. Strategy guides the financial planning

process by establishing overall business development guidelines and growth

targets. Which businesses does the firm want to

• enter

• expand

• contract

• exit

and how quickly?

Hence, the strategic plan sets the targets that we want to achieve.

5. 5. dia

Financial PlanningThe Financial Planning Process

A key factor in setting the strategy and the financial play is the length of the

planning horizon. The longer is the financial plan, the less detailed it should be

(in general).

The revision of a financial plan is generally a function of the length of the

planning horizon. Short-term plans are revised frequently, long-term plans are

revised much less frequently.

6. 6. dia

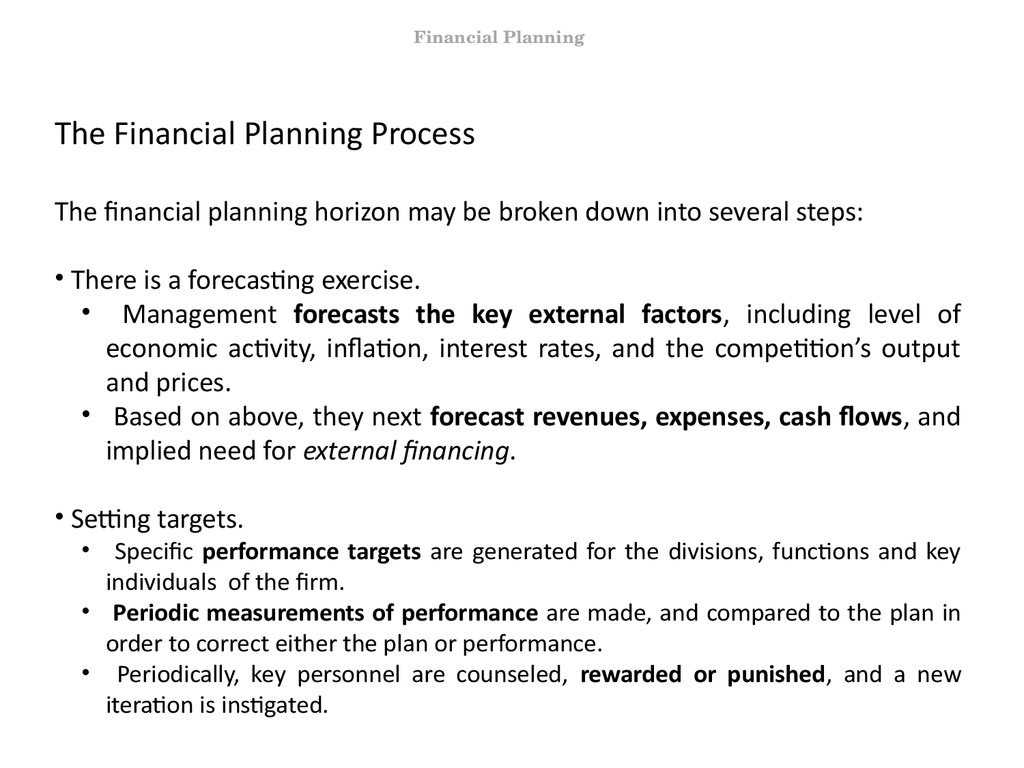

Financial PlanningThe Financial Planning Process

The financial planning horizon may be broken down into several steps:

• There is a forecasting exercise.

• Management forecasts the key external factors, including level of

economic activity, inflation, interest rates, and the competition’s output

and prices.

• Based on above, they next forecast revenues, expenses, cash flows, and

implied need for external financing.

• Setting targets.

• Specific performance targets are generated for the divisions, functions and key

individuals of the firm.

• Periodic measurements of performance are made, and compared to the plan in

order to correct either the plan or performance.

• Periodically, key personnel are counseled, rewarded or punished, and a new

iteration is instigated.

7. 7. dia

Financial PlanningThe Financial Planning Process – Remarks

• Some variables must be forecast well in advance because exploitation

requires a long lead-time, others may be reacted to immediately. If you are

the manager of a pharmaceutical company and think about developing a

medicine, then since it takes time to develop it you have to forecast well in

advance the potential demand for the medicine.

• Some variables are highly volatile, and can’t be forecast effectively, so the

best we can do is to plan for the unknown (contingency planning). If your

company works in a developing country with unstable macroeconomic

conditions, then forecasting inflation may be impossible.

• Planning horizons must be appropriate.

• For a magazine stand, a two year planning horizon may be far too long.

• A pharmaceutical business (with long new-plant construction lead-times,

and long drug development/testing/approval procedures) needs a

planning horizon that may be as long a ten years.

8. 8. dia

Financial PlanningThe Financial Planning Process – Remarks

• A plan should always lead to decisions that justify the cost of its preparation.

Proper planning is, in essence, part of the process of decision making. Any

part of a plan that does not lead to a decision is probably a waste of

managerial resources.

• A plan should make reasonable tradeoffs between flexibility and the cost of

flexibility.

9. 9. dia

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – an example

• Consider the following example of a fictional company called GPC.

• Let us have a look first at the income statements and the balance sheets of

the last three years!

• Assume that it is all that we know about the company. (We are the new

managers and we have been just hired.) How can we prepare the financial

plan for the next year?

• Assume also that taxes are 40% of the earnings after interest expenses are

deducted.

• Assume also that 30% of the earnings after taxes is paid out as dividend.

10. 10. dia

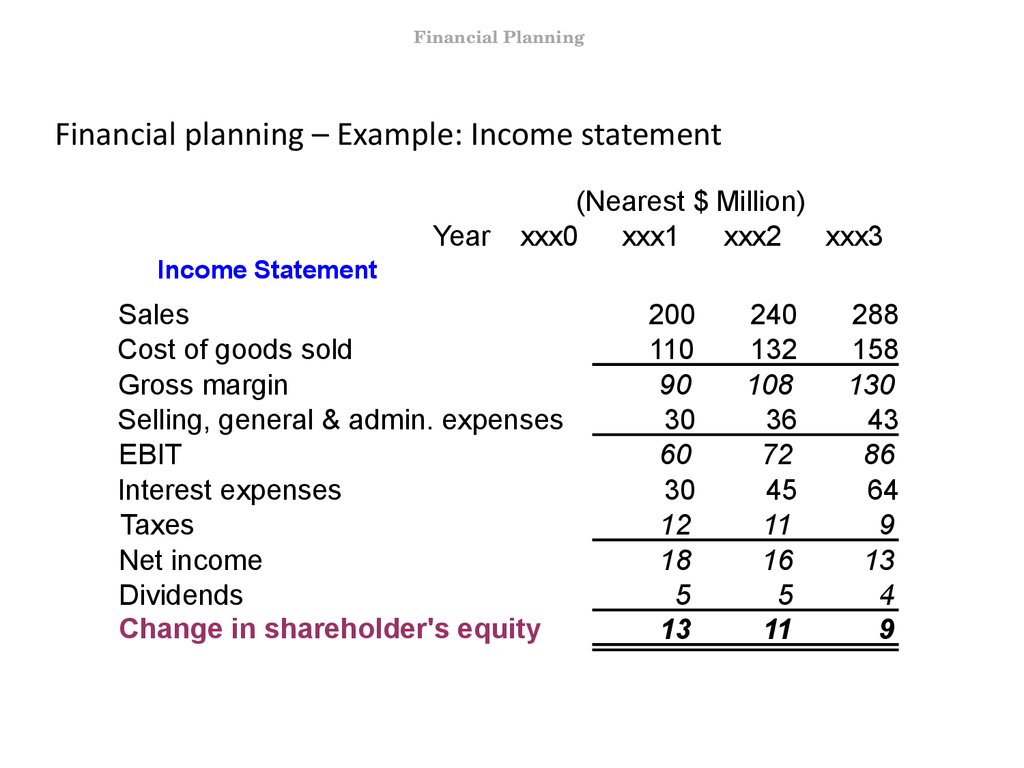

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – Example: Income statement

Year

(Nearest $ Million)

xxx0

xxx1

xxx2

xxx3

Income Statement

Sales

Cost of goods sold

Gross margin

Selling, general & admin. expenses

EBIT

Interest expenses

Taxes

Net income

Dividends

Change in shareholder's equity

200

110

90

30

60

30

12

18

5

13

240

132

108

36

72

45

11

16

5

11

288

158

130

43

86

64

9

13

4

9

11. 11. dia

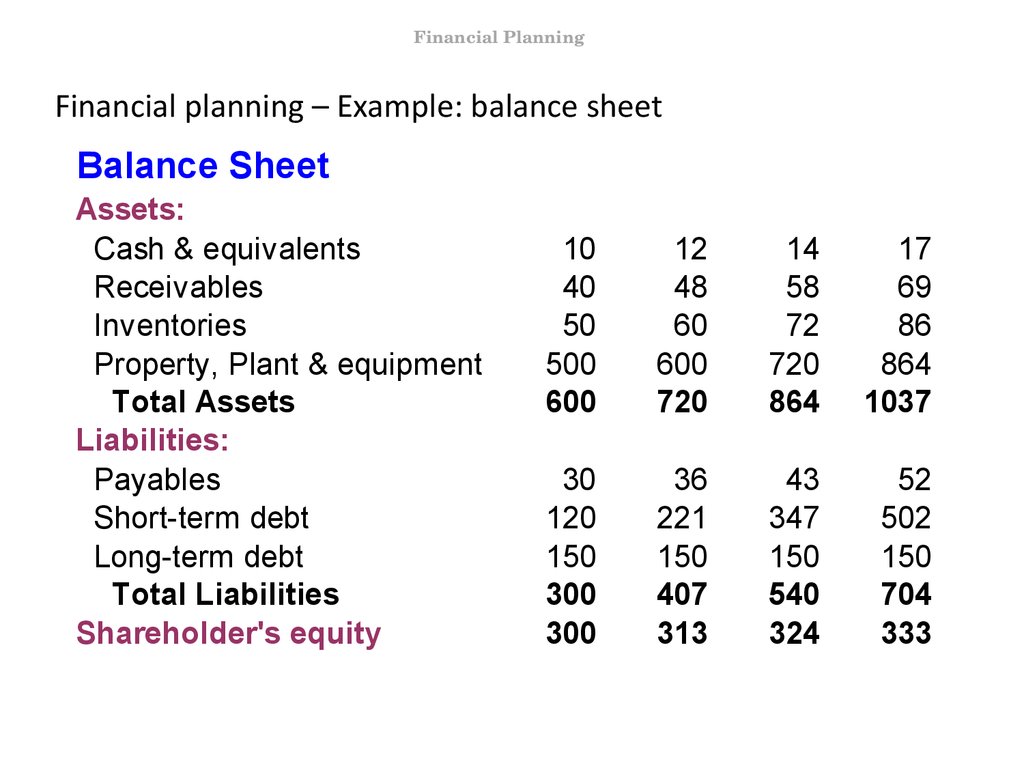

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – Example: balance sheet

Balance Sheet

Assets:

Cash & equivalents

Receivables

Inventories

Property, Plant & equipment

Total Assets

Liabilities:

Payables

Short-term debt

Long-term debt

Total Liabilities

Shareholder's equity

10

40

50

500

600

12

48

60

600

720

14

58

72

720

864

17

69

86

864

1037

30

120

150

300

300

36

221

150

407

313

43

347

150

540

324

52

502

150

704

333

12. 12. dia

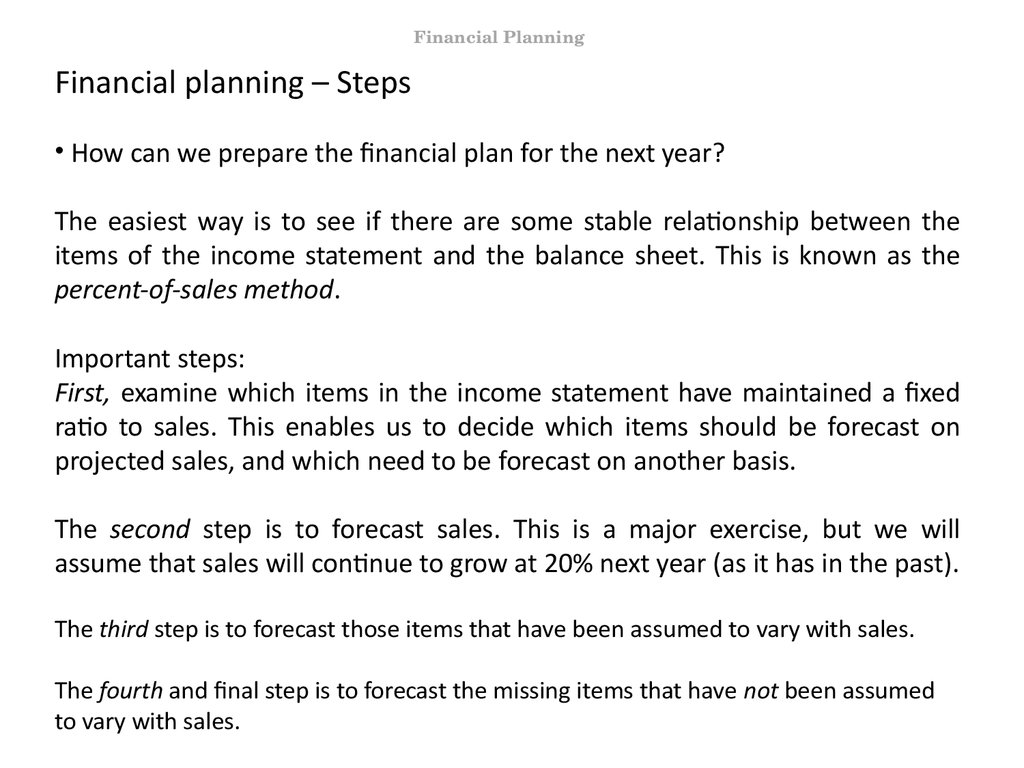

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – Steps

• How can we prepare the financial plan for the next year?

The easiest way is to see if there are some stable relationship between the

items of the income statement and the balance sheet. This is known as the

percent-of-sales method.

Important steps:

First, examine which items in the income statement have maintained a fixed

ratio to sales. This enables us to decide which items should be forecast on

projected sales, and which need to be forecast on another basis.

The second step is to forecast sales. This is a major exercise, but we will

assume that sales will continue to grow at 20% next year (as it has in the past).

The third step is to forecast those items that have been assumed to vary with sales.

The fourth and final step is to forecast the missing items that have not been assumed

to vary with sales.

13. 13. dia

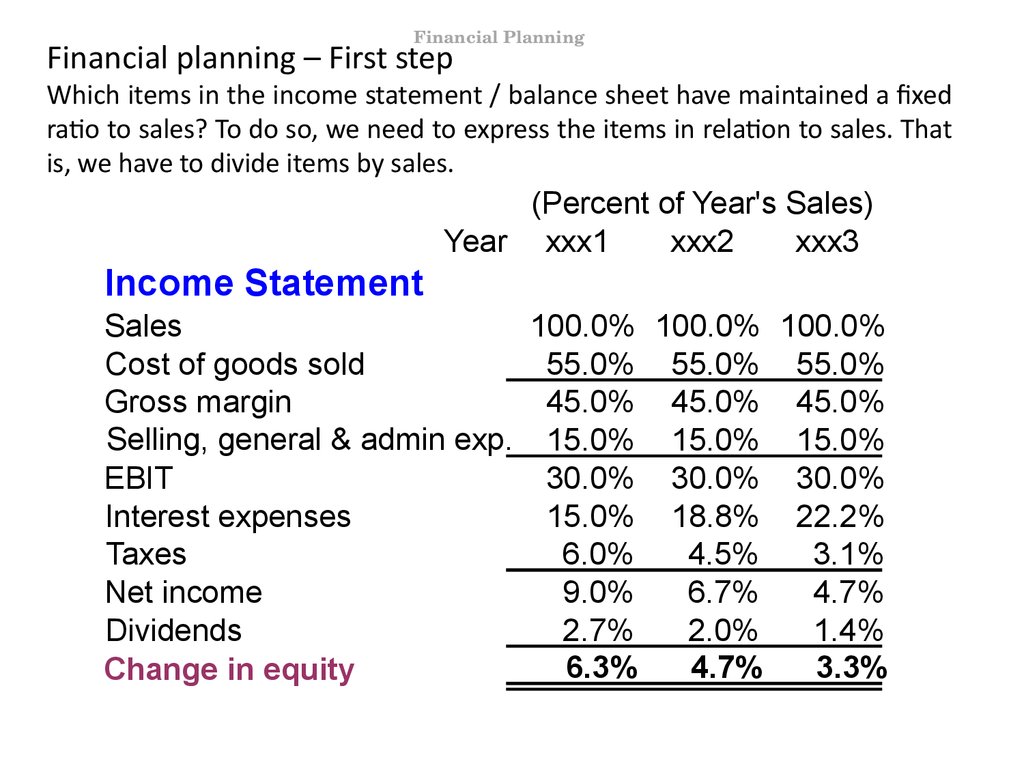

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – First step

Which items in the income statement / balance sheet have maintained a fixed

ratio to sales? To do so, we need to express the items in relation to sales. That

is, we have to divide items by sales.

(Percent of Year's Sales)

Year xxx1

xxx2

xxx3

Income Statement

Sales

100.0% 100.0% 100.0%

Cost of goods sold

55.0% 55.0% 55.0%

Gross margin

45.0% 45.0% 45.0%

Selling, general & admin exp. 15.0% 15.0% 15.0%

EBIT

30.0% 30.0% 30.0%

Interest expenses

15.0% 18.8% 22.2%

Taxes

6.0%

4.5%

3.1%

Net income

9.0%

6.7%

4.7%

Dividends

2.7%

2.0%

1.4%

6.3%

4.7%

3.3%

Change in equity

14. 14. dia

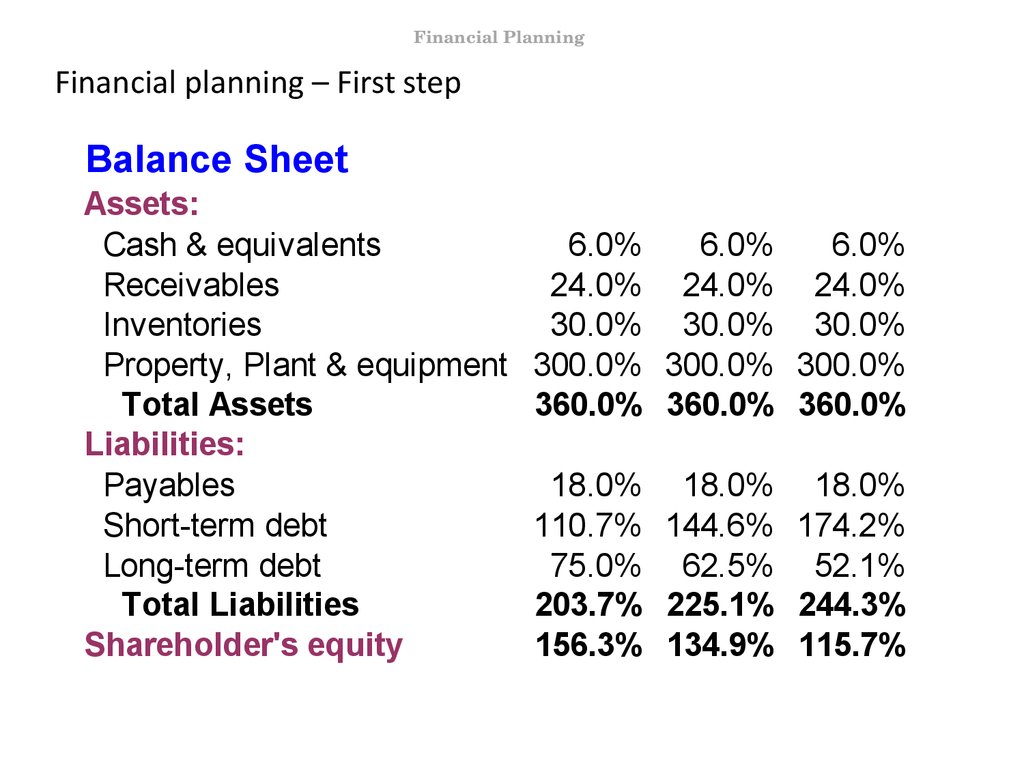

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – First step

Balance Sheet

Assets:

Cash & equivalents

Receivables

Inventories

Property, Plant & equipment

Total Assets

Liabilities:

Payables

Short-term debt

Long-term debt

Total Liabilities

Shareholder's equity

6.0%

6.0%

6.0%

24.0% 24.0% 24.0%

30.0% 30.0% 30.0%

300.0% 300.0% 300.0%

360.0% 360.0% 360.0%

18.0% 18.0% 18.0%

110.7% 144.6% 174.2%

75.0% 62.5% 52.1%

203.7% 225.1% 244.3%

156.3% 134.9% 115.7%

15. 15. dia

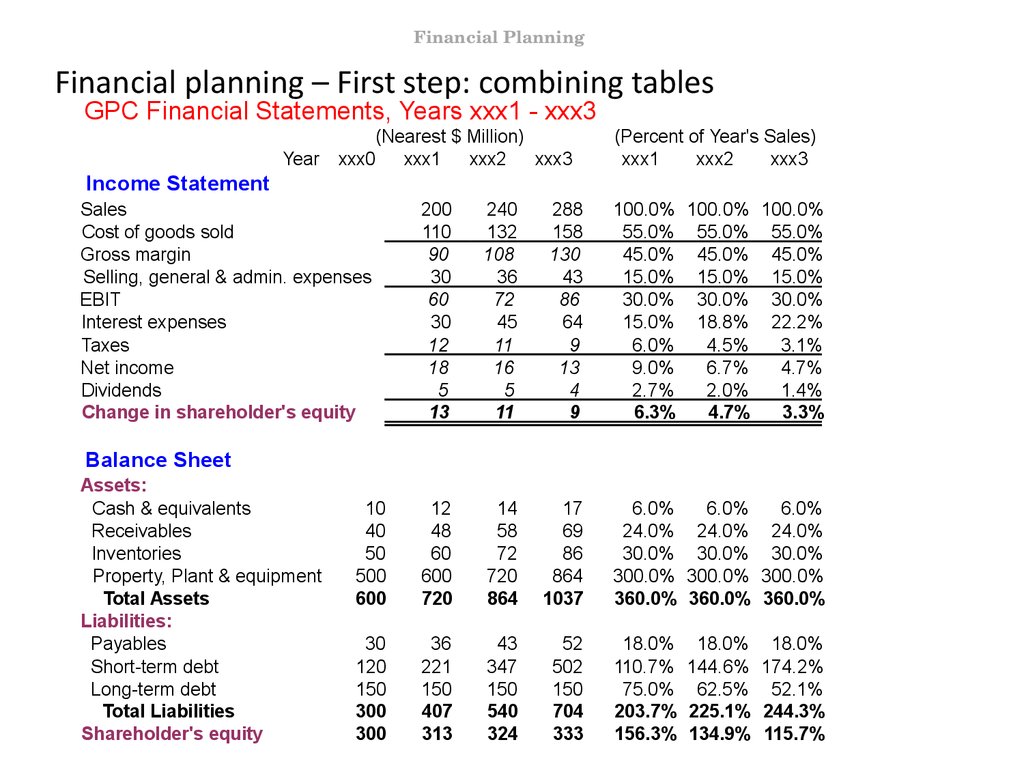

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – First step: combining tables

GPC Financial Statements, Years xxx1 - xxx3

Year

(Nearest $ Million)

xxx0

xxx1

xxx2

xxx3

(Percent of Year's Sales)

xxx1

xxx2

xxx3

Income Statement

Sales

Cost of goods sold

Gross margin

Selling, general & admin. expenses

EBIT

Interest expenses

Taxes

Net income

Dividends

Change in shareholder's equity

200

110

90

30

60

30

12

18

5

13

240

132

108

36

72

45

11

16

5

11

288

158

130

43

86

64

9

13

4

9

100.0% 100.0% 100.0%

55.0% 55.0% 55.0%

45.0% 45.0% 45.0%

15.0% 15.0% 15.0%

30.0% 30.0% 30.0%

15.0% 18.8% 22.2%

6.0%

4.5%

3.1%

9.0%

6.7%

4.7%

2.7%

2.0%

1.4%

6.3%

4.7%

3.3%

10

40

50

500

600

12

48

60

600

720

14

58

72

720

864

17

69

86

864

1037

6.0%

6.0%

6.0%

24.0% 24.0% 24.0%

30.0% 30.0% 30.0%

300.0% 300.0% 300.0%

360.0% 360.0% 360.0%

30

120

150

300

300

36

221

150

407

313

43

347

150

540

324

52

502

150

704

333

18.0% 18.0% 18.0%

110.7% 144.6% 174.2%

75.0% 62.5% 52.1%

203.7% 225.1% 244.3%

156.3% 134.9% 115.7%

Balance Sheet

Assets:

Cash & equivalents

Receivables

Inventories

Property, Plant & equipment

Total Assets

Liabilities:

Payables

Short-term debt

Long-term debt

Total Liabilities

Shareholder's equity

16. 16. dia

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – First step

• We compare everything to sales since sales represents the outcome of the

main performance of the company.

• We see that costs of goods sold, gross margin and SGA expenses have a fixed

ratio to sales. (Obviously, in real life these ratios are not that stable.) As a

consequence, EBIT is also a stable share of sales. However, the share of

interest expenses is not stable.

• Similarly, all items of the asset side has a fixed ratio to sales. It is not the case

for liabilities as there only payables have a fixed ratio, while short-term and

long-term debt has an unstable relation to sales.

17. 17. dia

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – Second and third step

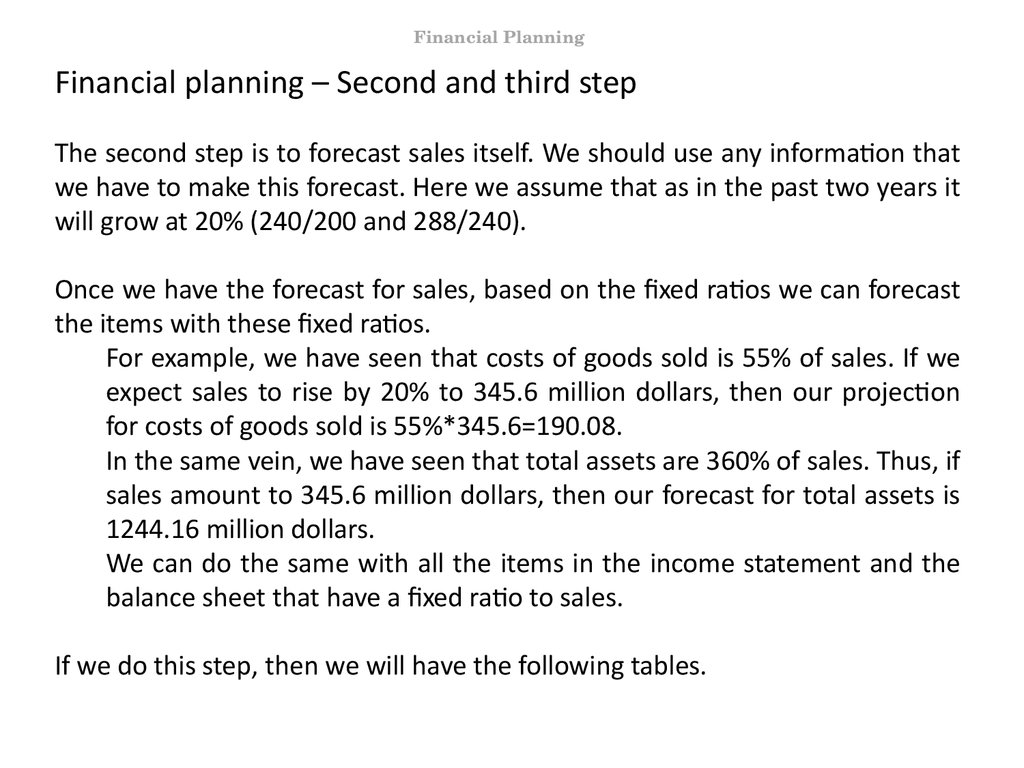

The second step is to forecast sales itself. We should use any information that

we have to make this forecast. Here we assume that as in the past two years it

will grow at 20% (240/200 and 288/240).

Once we have the forecast for sales, based on the fixed ratios we can forecast

the items with these fixed ratios.

For example, we have seen that costs of goods sold is 55% of sales. If we

expect sales to rise by 20% to 345.6 million dollars, then our projection

for costs of goods sold is 55%*345.6=190.08.

In the same vein, we have seen that total assets are 360% of sales. Thus, if

sales amount to 345.6 million dollars, then our forecast for total assets is

1244.16 million dollars.

We can do the same with all the items in the income statement and the

balance sheet that have a fixed ratio to sales.

If we do this step, then we will have the following tables.

18. 18. dia

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – Second and third step

• Note that there are still some numbers missing.

19. 19. dia

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – Second and third step

• Note that there are still some numbers missing.

20. 20. dia

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – Fourth step: completing the income statement

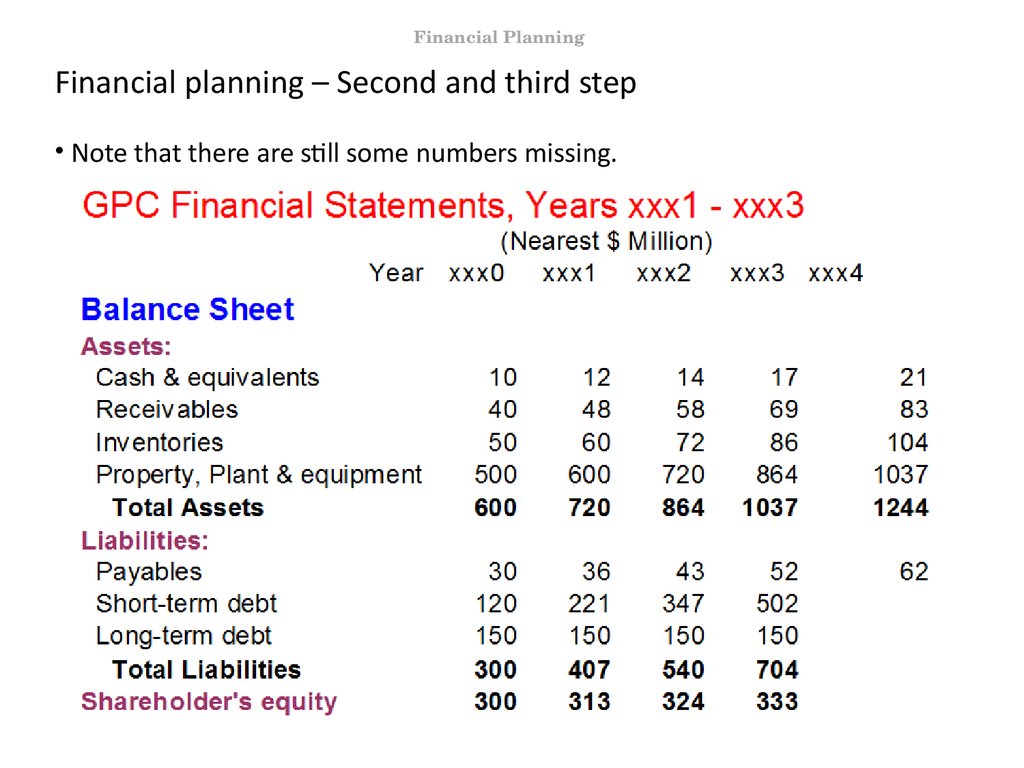

We need to fill in the missing numbers. To do so we use any information that

may help.

Note that we need to find out the interest rate expenses (and then we can

calculate also taxes) in the income statements. Interest is paid on debt that

appears on the liability side of the balance sheet.

Let us assume that interest rate on long-term debt is 8%, and on short-term debt is

15%. Since the outstanding short-term debt is 501.72 million dollars, and the

outstanding long-term debt is 150 million dollars, so the interest to be paid is

0.08*501.72 + 0.15*150 = 87.26. Hence, taxes 0.4*(103.68-87.26)=6.57 million dollars.

In fact, this information on interest rates is generally known.

Since the dividend pay-out ratio is given (30% of the net income), we can

compute it as well. Net income=103.86-87.26-6.57=9.85, so the dividend is

2.96.

The part of the net income that is not paid out as dividend increases the

shareholder’s equity, that is the wealth of the shareholders. In our case, it is

9.85-2.96=6.9 million dollars.

We have completed the income statement!

21. 21. dia

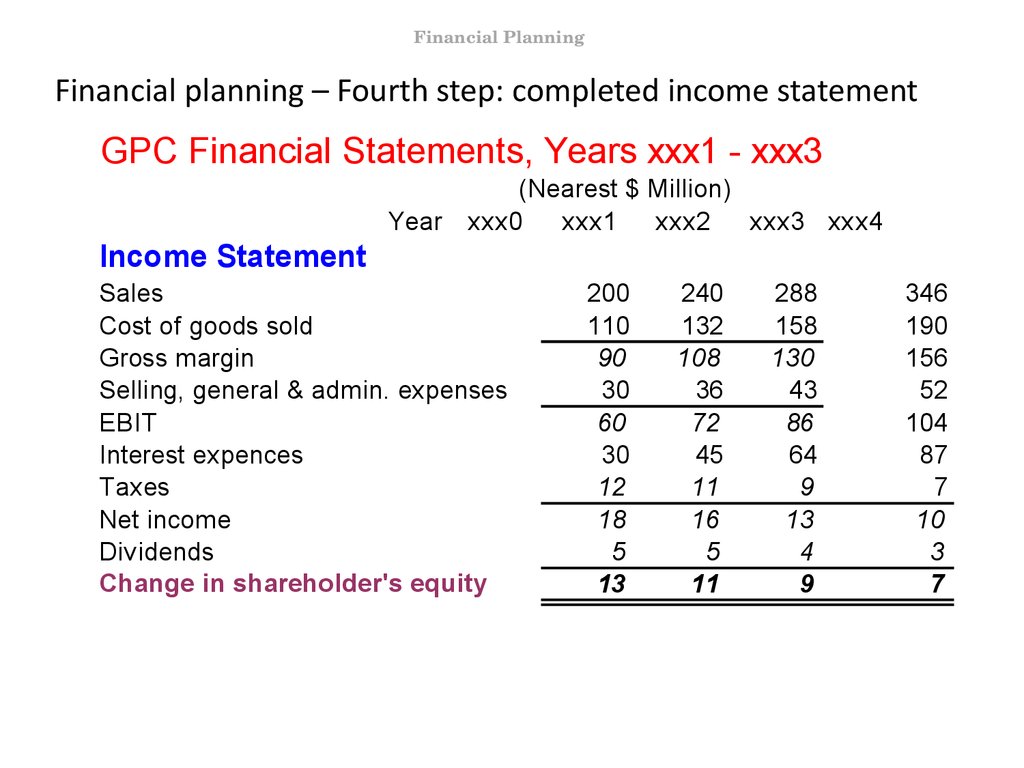

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – Fourth step: completed income statement

GPC Financial Statements, Years xxx1 - xxx3

(Nearest $ Million)

Year xxx0 xxx1 xxx2 xxx3 xxx4

Income Statement

Sales

Cost of goods sold

Gross margin

Selling, general & admin. expenses

EBIT

Interest expences

Taxes

Net income

Dividends

Change in shareholder's equity

200

110

90

30

60

30

12

18

5

13

240

132

108

36

72

45

11

16

5

11

288

158

130

43

86

64

9

13

4

9

346

190

156

52

104

87

7

10

3

7

22. 22. dia

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – Fourth step: completing the balance sheet

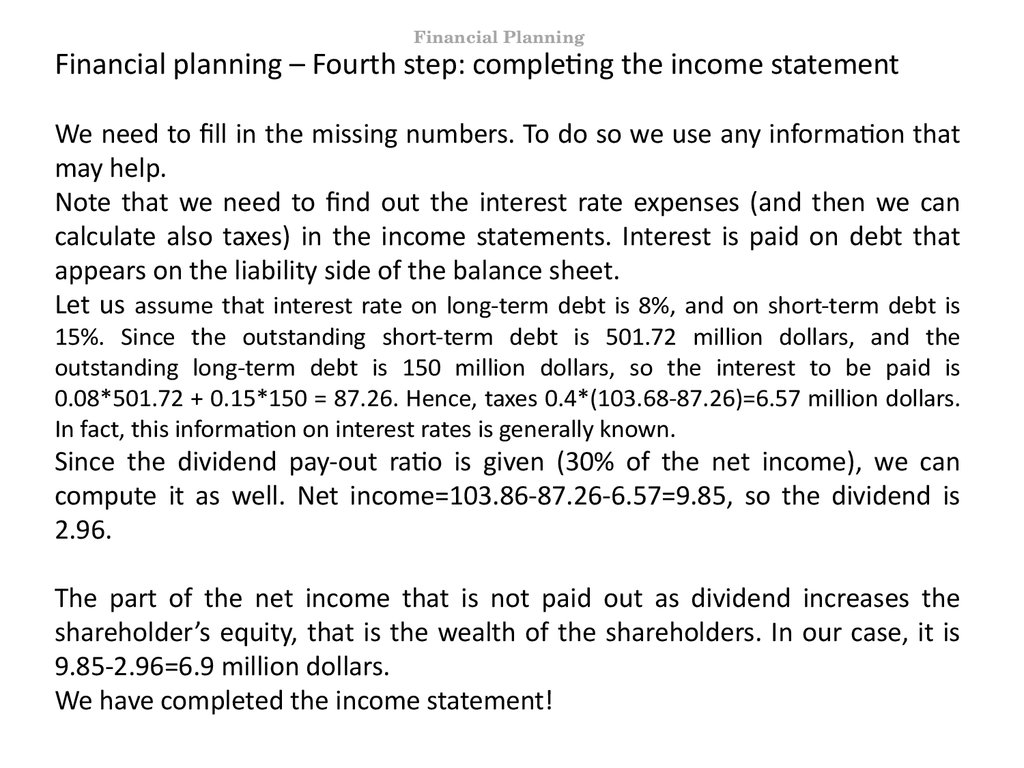

We have obtained the change in the shareholder’s equity so we can calculate

the shareholder’s equity in the balance sheet by adding this change to the last

years shareholder’s equity. That is, 333.24+6.9=340.14.

There are two missing numbers in the balance sheet: short-term and longterm debt.

We know that total asset = total liability + equity, so total liability= total asset –

equity, that is total liability= 1244.16 -340.14=904.02. From the liability items

we have forecasted already payables to be 62.21. Then, short-term debt +

long-term debt = total liabilites – payables = 904.02-62.21=841.41.

To see how much of this sum goes to these debts we need additional

assumptions. Assume that there is no change in long-term debt. Then, short-term

debt =$841.41 - 150 = $691.81 million.

We have completed the balance sheet! We have prepared a financial plan for

the next year.

23. 23. dia

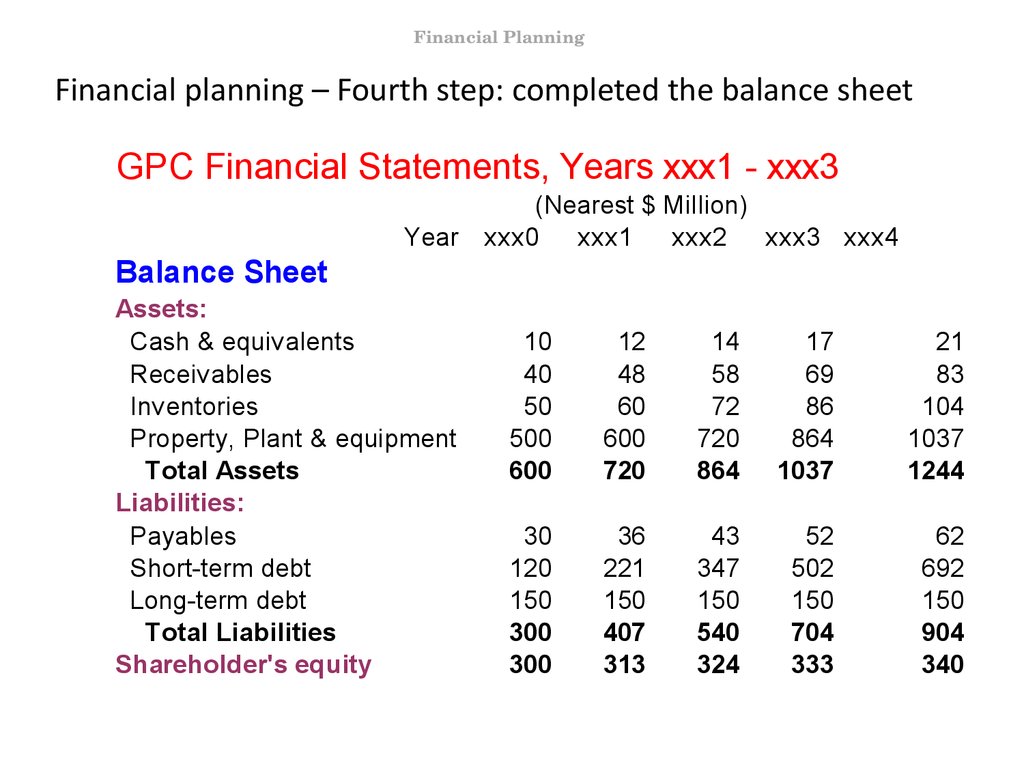

Financial PlanningFinancial planning – Fourth step: completed the balance sheet

GPC Financial Statements, Years xxx1 - xxx3

(Nearest $ Million)

Year xxx0 xxx1 xxx2 xxx3 xxx4

Balance Sheet

Assets:

Cash & equivalents

Receivables

Inventories

Property, Plant & equipment

Total Assets

Liabilities:

Payables

Short-term debt

Long-term debt

Total Liabilities

Shareholder's equity

10

40

50

500

600

12

48

60

600

720

14

58

72

720

864

17

69

86

864

1037

21

83

104

1037

1244

30

120

150

300

300

36

221

150

407

313

43

347

150

540

324

52

502

150

704

333

62

692

150

904

340

24. 24. dia

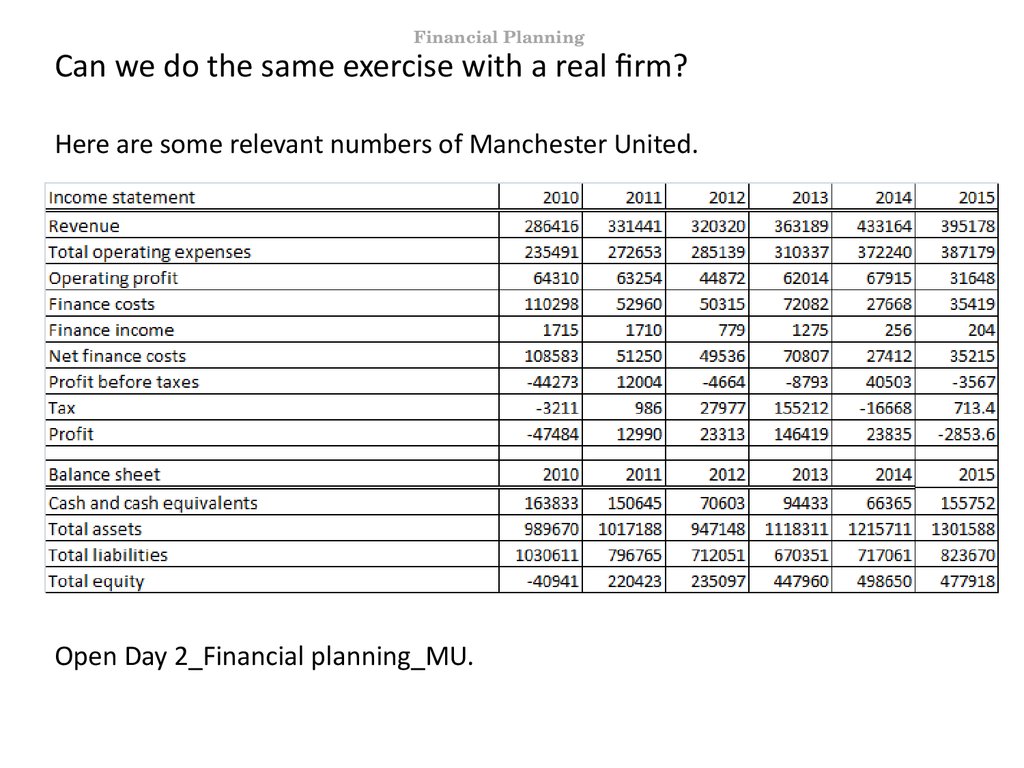

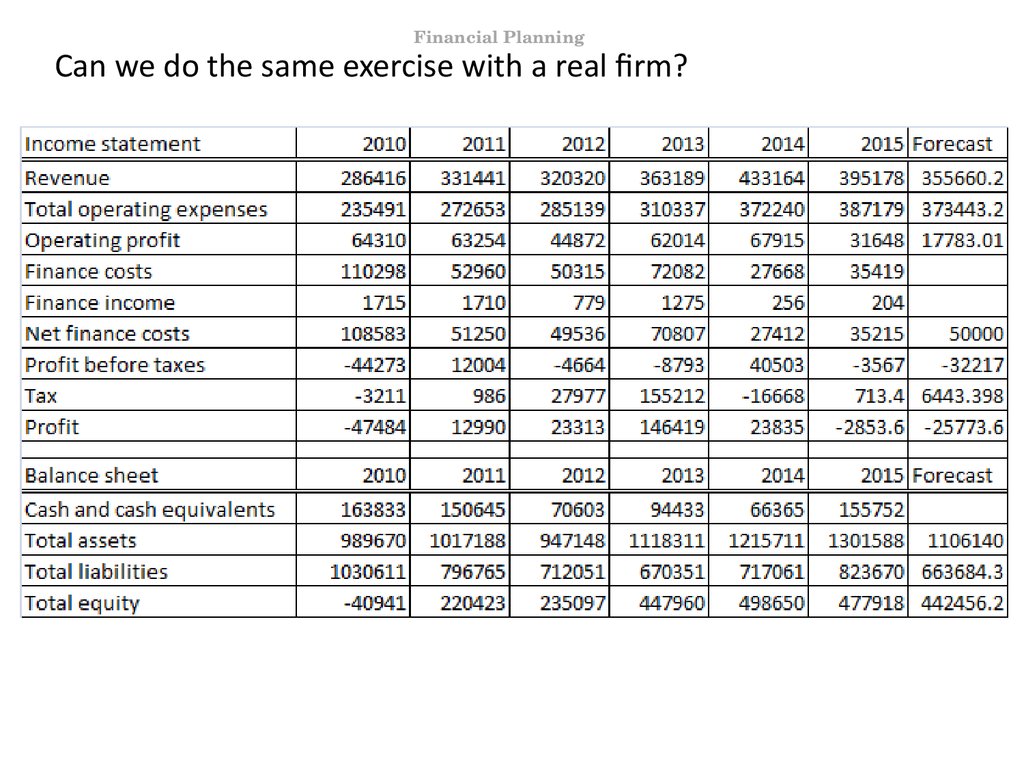

Financial PlanningCan we do the same exercise with a real firm?

Here are some relevant numbers of Manchester United.

Open Day 2_Financial planning_MU.

25. 25. dia

Financial PlanningCan we do the same exercise with a real firm?

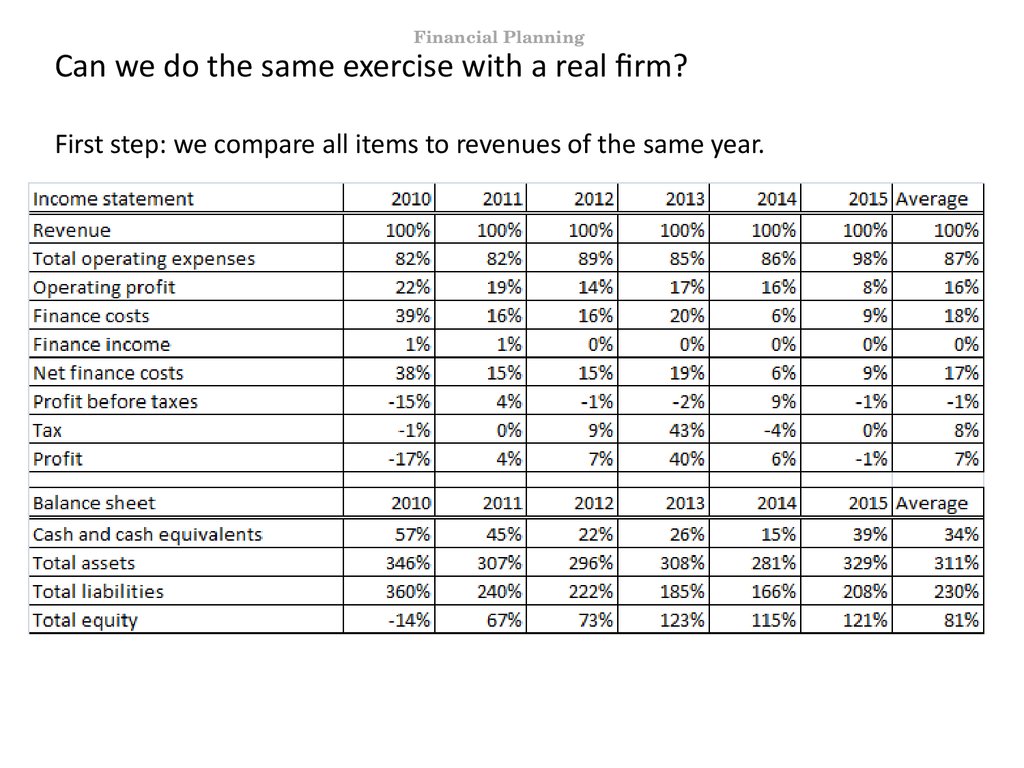

First step: we compare all items to revenues of the same year.

26. 26. dia

Financial PlanningCan we do the same exercise with a real firm?

Obviously, here the number are not as nice as before, but still we see some

quite stable ratios. Total operating expenses and operating profits are quite

stable, the do not vary much. Total operating expenses have possibly grown

compared to revenues as MU is not as successful as before, so has less

revenue, but still has to pay a lot to its star players. Operating profits are a bit

lower than the average due to the same reason. Total assets are also stable

around 300%.

Second step is to forecast revenues. It is easy to calculate the change in

revenues for the last years. These numbers are: 16% for 2011, -3% for 2012,

13% for 2013, 19% for 2014 and -9% for 2015. The average is about 7%. We

may implement this number with additional information. For instance, we

think that MU is not going to play in any international tournament next year,

leading to a 10% decrease in revenue! Then for 2016 we expect it to be

355660.2.

Now, based on the fixed ratios we can forecast the items with fixed ratios.

Which items do we consider to have a fixed ratio. On the next slide I also

represent the averages of the percentages.

27. 27. dia

Financial PlanningCan we do the same exercise with a real firm?

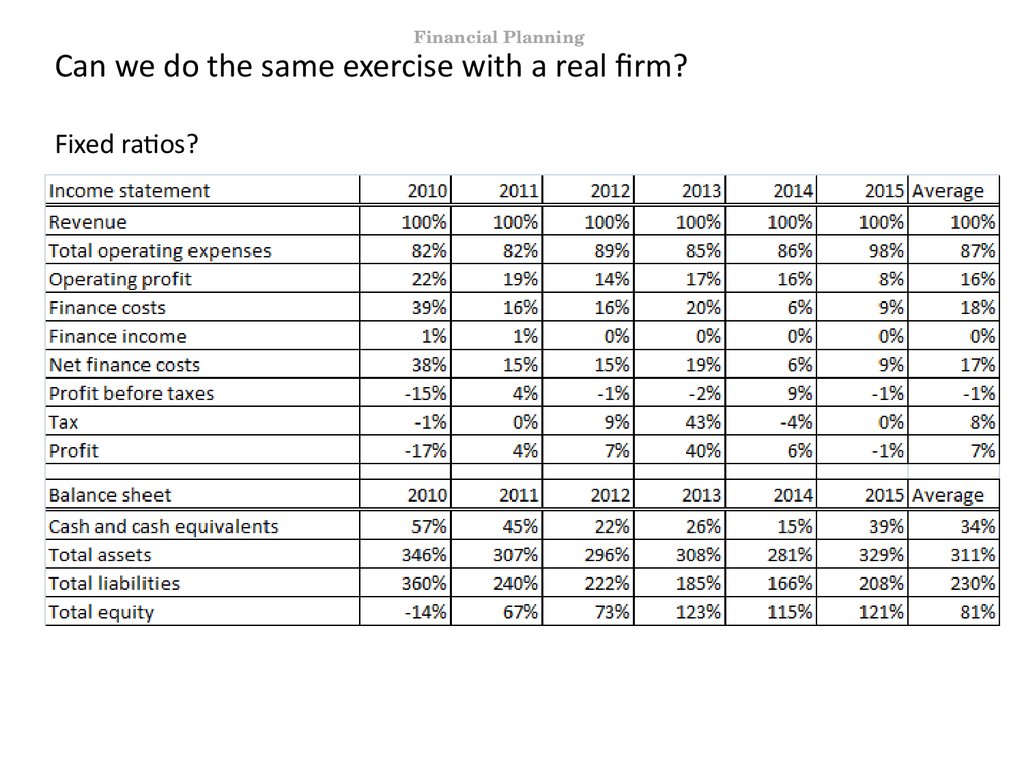

Fixed ratios?

28. 28. dia

Financial PlanningCan we do the same exercise with a real firm?

Fixed ratios?

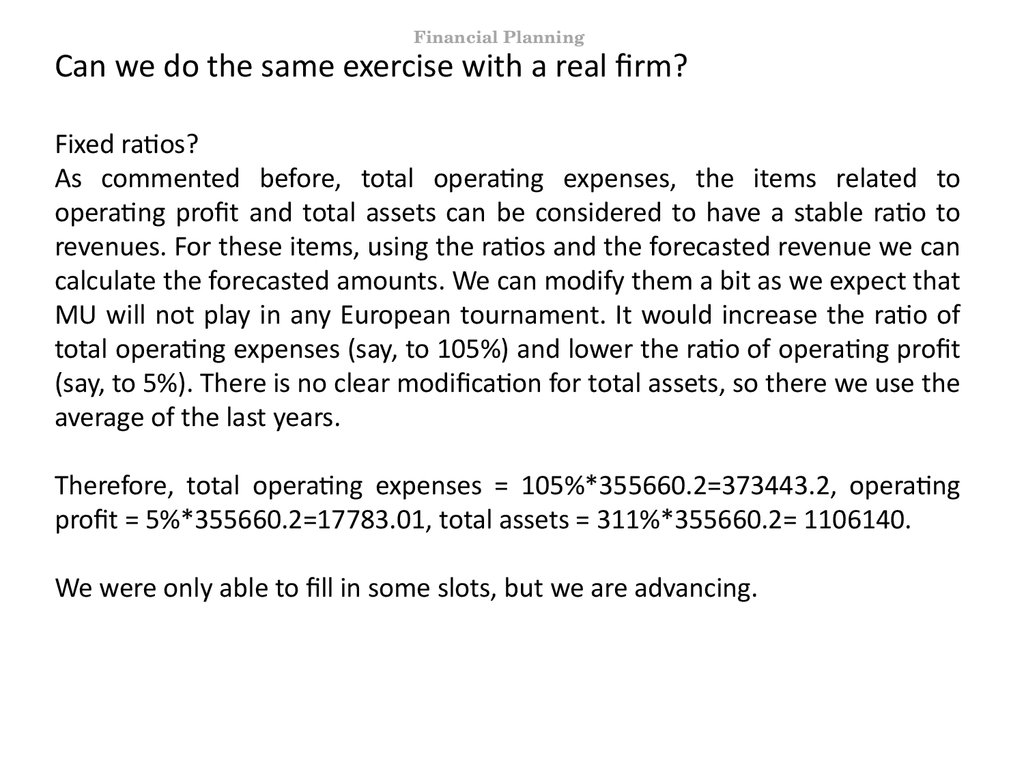

As commented before, total operating expenses, the items related to

operating profit and total assets can be considered to have a stable ratio to

revenues. For these items, using the ratios and the forecasted revenue we can

calculate the forecasted amounts. We can modify them a bit as we expect that

MU will not play in any European tournament. It would increase the ratio of

total operating expenses (say, to 105%) and lower the ratio of operating profit

(say, to 5%). There is no clear modification for total assets, so there we use the

average of the last years.

Therefore, total operating expenses = 105%*355660.2=373443.2, operating

profit = 5%*355660.2=17783.01, total assets = 311%*355660.2= 1106140.

We were only able to fill in some slots, but we are advancing.

29. 29. dia

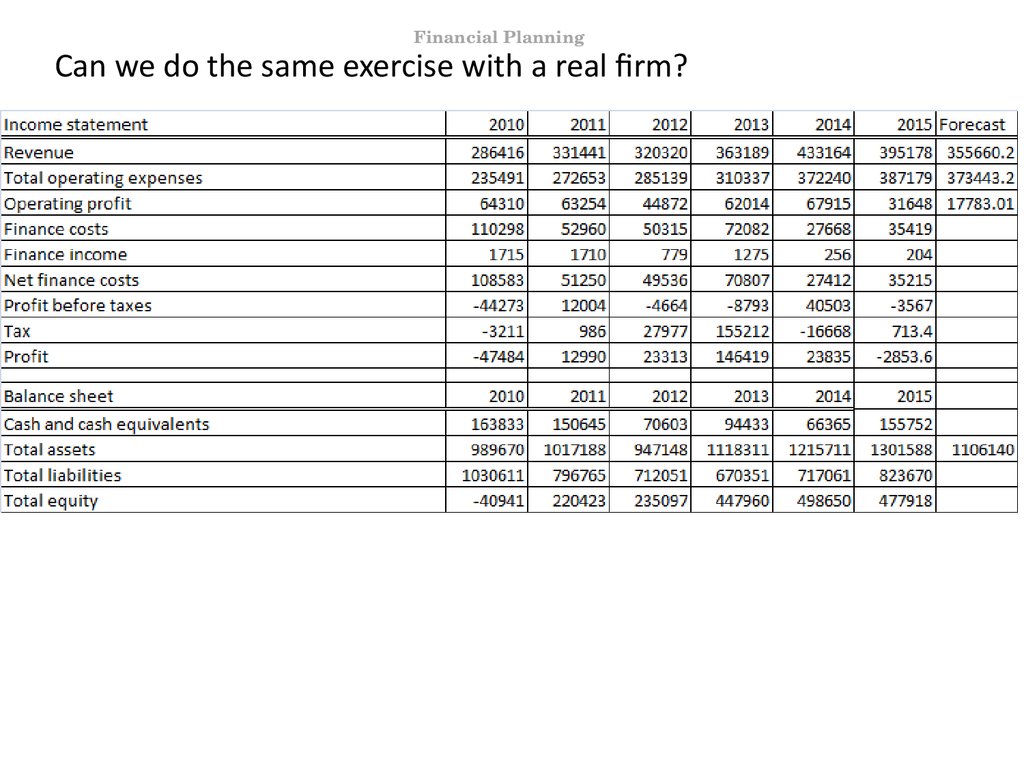

Financial PlanningCan we do the same exercise with a real firm?

30. 30. dia

Financial PlanningCan we do the same exercise with a real firm?

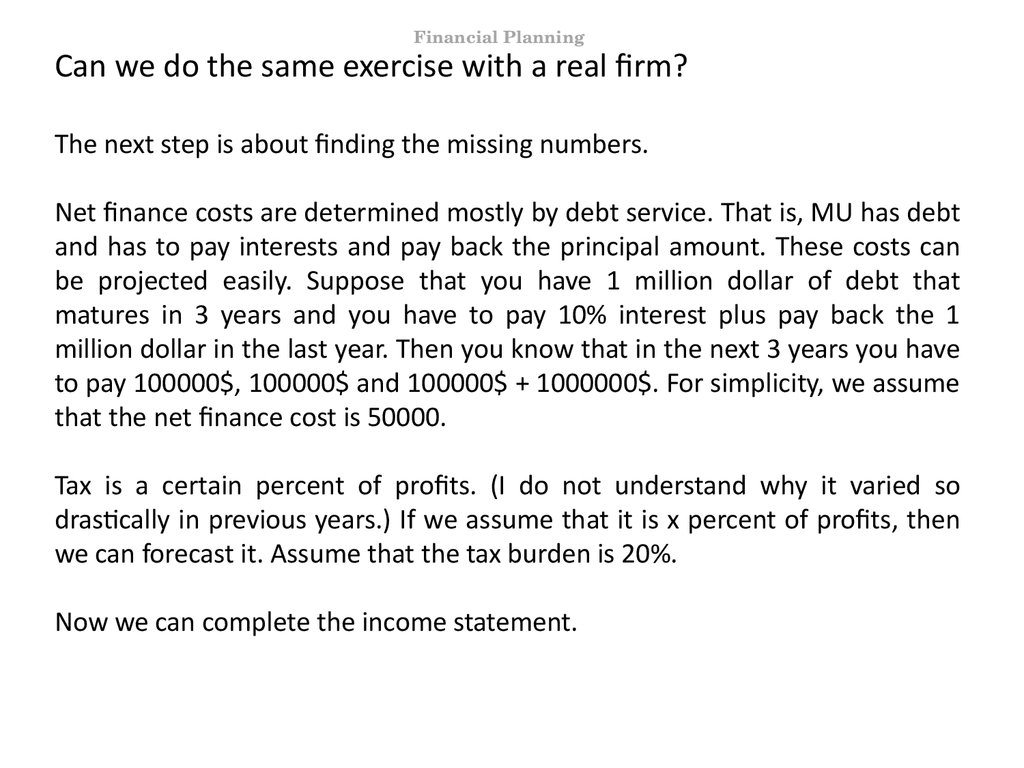

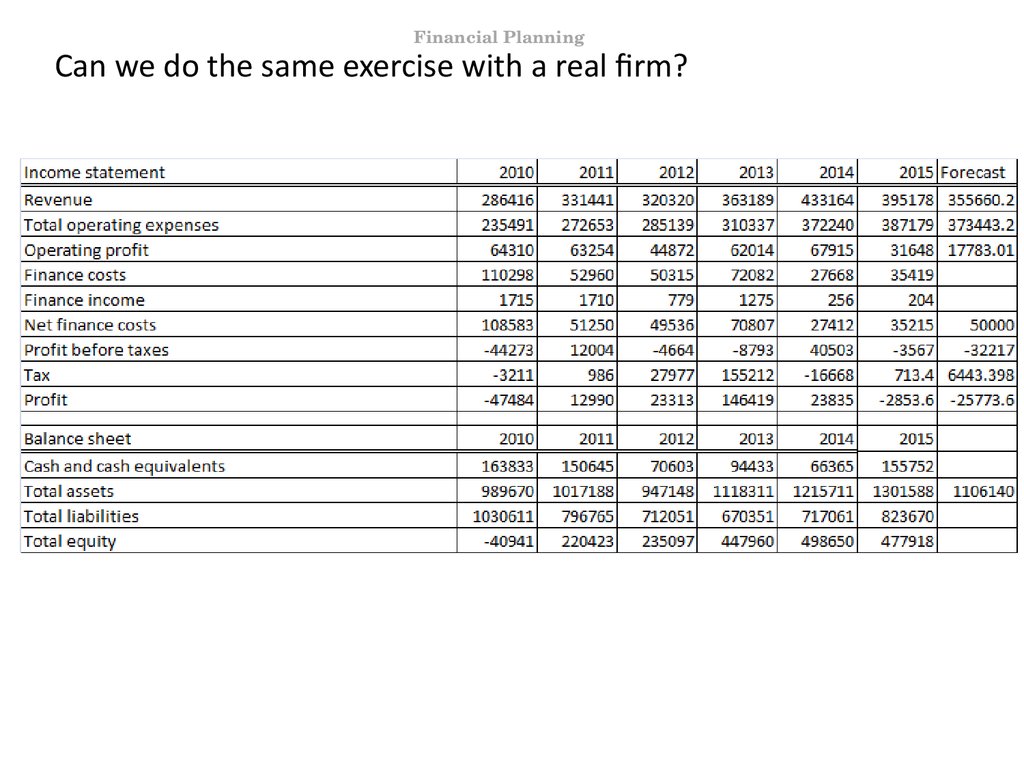

The next step is about finding the missing numbers.

Net finance costs are determined mostly by debt service. That is, MU has debt

and has to pay interests and pay back the principal amount. These costs can

be projected easily. Suppose that you have 1 million dollar of debt that

matures in 3 years and you have to pay 10% interest plus pay back the 1

million dollar in the last year. Then you know that in the next 3 years you have

to pay 100000$, 100000$ and 100000$ + 1000000$. For simplicity, we assume

that the net finance cost is 50000.

Tax is a certain percent of profits. (I do not understand why it varied so

drastically in previous years.) If we assume that it is x percent of profits, then

we can forecast it. Assume that the tax burden is 20%.

Now we can complete the income statement.

31. 31. dia

Financial PlanningCan we do the same exercise with a real firm?

32. 32. dia

Financial PlanningCan we do the same exercise with a real firm?

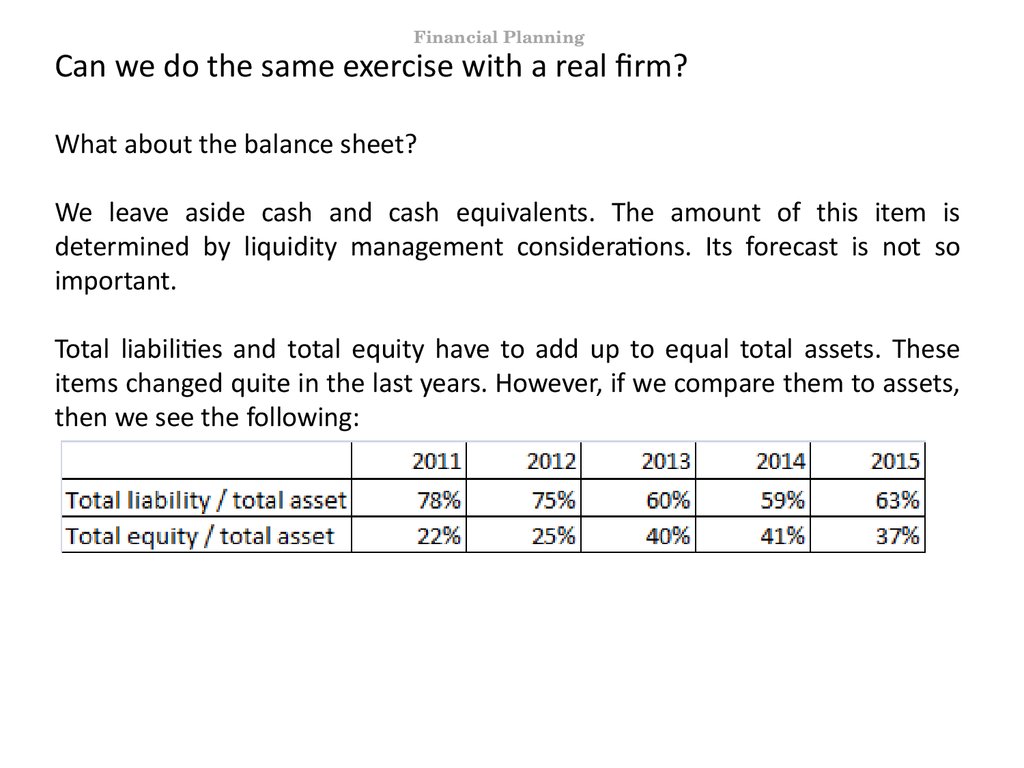

What about the balance sheet?

We leave aside cash and cash equivalents. The amount of this item is

determined by liquidity management considerations. Its forecast is not so

important.

Total liabilities and total equity have to add up to equal total assets. These

items changed quite in the last years. However, if we compare them to assets,

then we see the following:

33. 33. dia

Financial PlanningCan we do the same exercise with a real firm?

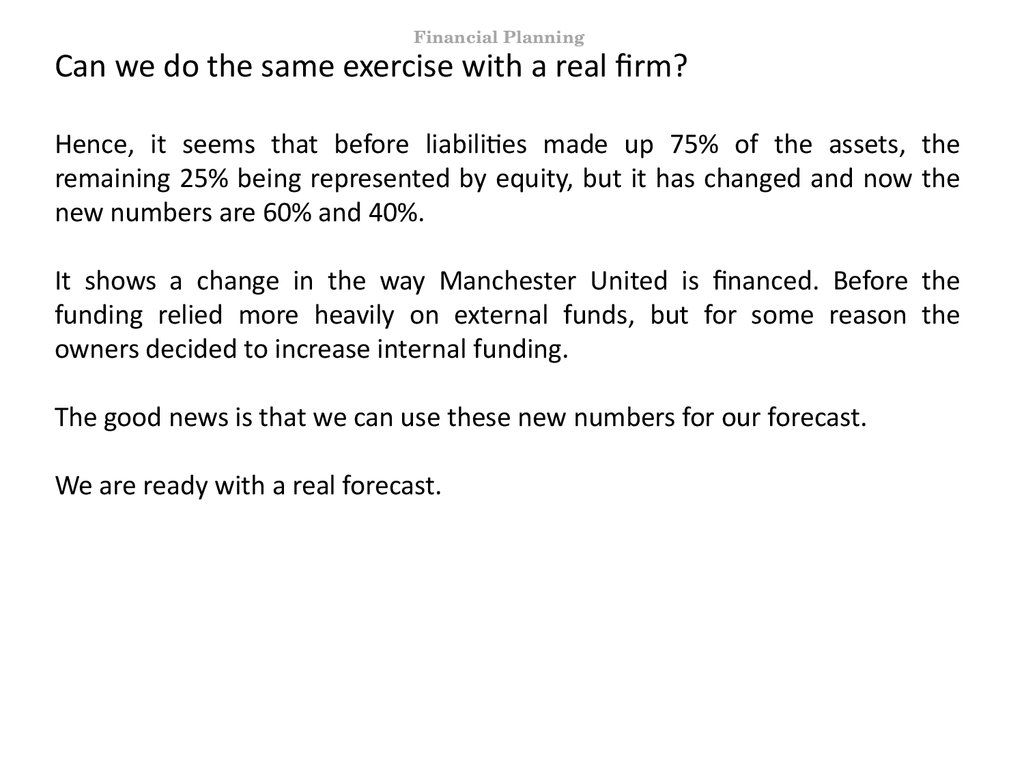

Hence, it seems that before liabilities made up 75% of the assets, the

remaining 25% being represented by equity, but it has changed and now the

new numbers are 60% and 40%.

It shows a change in the way Manchester United is financed. Before the

funding relied more heavily on external funds, but for some reason the

owners decided to increase internal funding.

The good news is that we can use these new numbers for our forecast.

We are ready with a real forecast.

34. 34. dia

Financial PlanningCan we do the same exercise with a real firm?

35. 35. dia

Assignment 2Financial Planning

Choose any company that has on its website the data (balance

sheet and income statement) that we used. Focus only on the

main items.

Income statement

• Revenue / sales

• Costs / expenses

• Profit before taxes

• Tax

• Profit

Balance sheet

• Total assets

• Total liabilities

• Total equity

Based on the numbers of the last years (at least 3 years) prepare

a financial plan.

36. 36. dia

Assignment 2Financial Planning

Choose wisely the company as you may need to come up with

assumptions as we did and those assumption should be justified.

(Hint: choose a big, well-known company.)

37. 37. dia

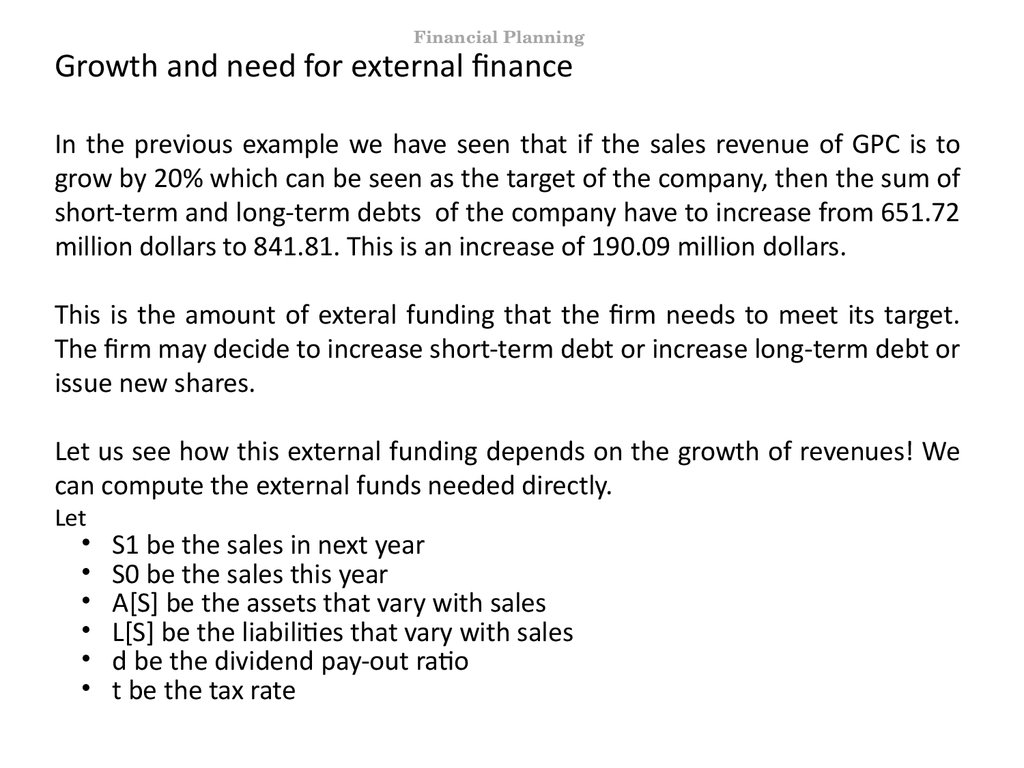

Financial PlanningGrowth and need for external finance

In the previous example we have seen that if the sales revenue of GPC is to

grow by 20% which can be seen as the target of the company, then the sum of

short-term and long-term debts of the company have to increase from 651.72

million dollars to 841.81. This is an increase of 190.09 million dollars.

This is the amount of exteral funding that the firm needs to meet its target.

The firm may decide to increase short-term debt or increase long-term debt or

issue new shares.

Let us see how this external funding depends on the growth of revenues! We

can compute the external funds needed directly.

Let

S1 be the sales in next year

S0 be the sales this year

A[S] be the assets that vary with sales

L[S] be the liabilities that vary with sales

d be the dividend pay-out ratio

t be the tax rate

38. 38. dia

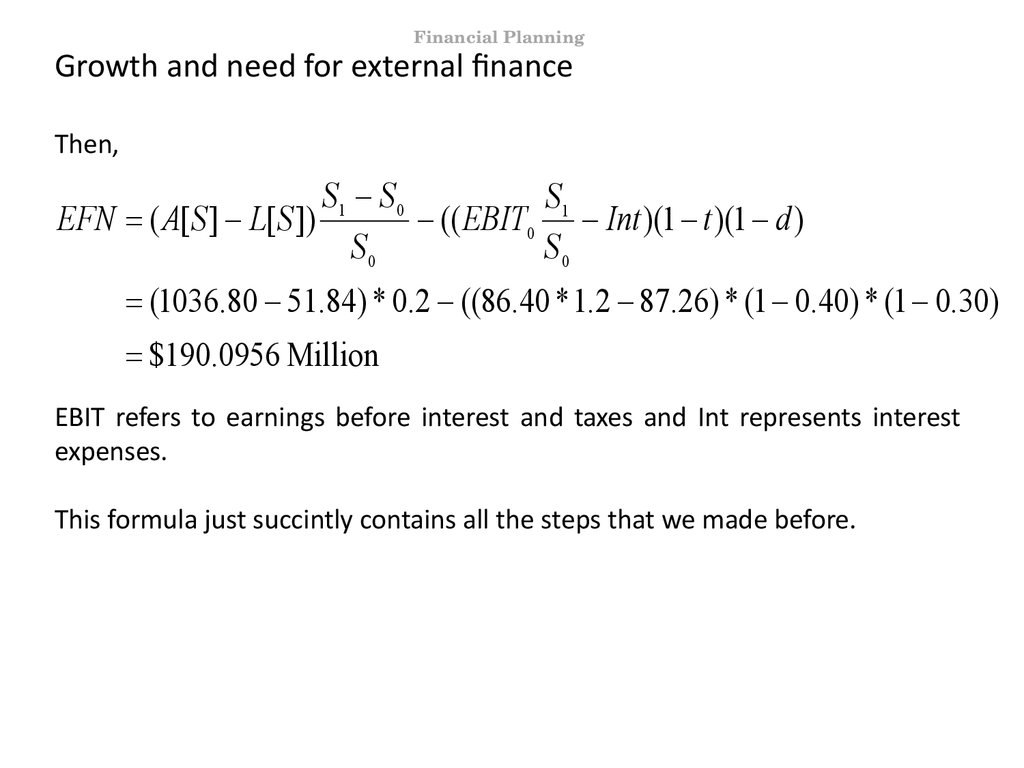

Financial PlanningGrowth and need for external finance

Then,

S1 S 0

S1

EFN ( A[ S ] L[ S ])

(( EBIT0 Int )(1 t )(1 d )

S0

S0

(1036.80 51.84) * 0.2 ((86.40 * 1.2 87.26) * (1 0.40) * (1 0.30)

$190.0956 Million

EBIT refers to earnings before interest and taxes and Int represents interest

expenses.

This formula just succintly contains all the steps that we made before.

39. 39. dia

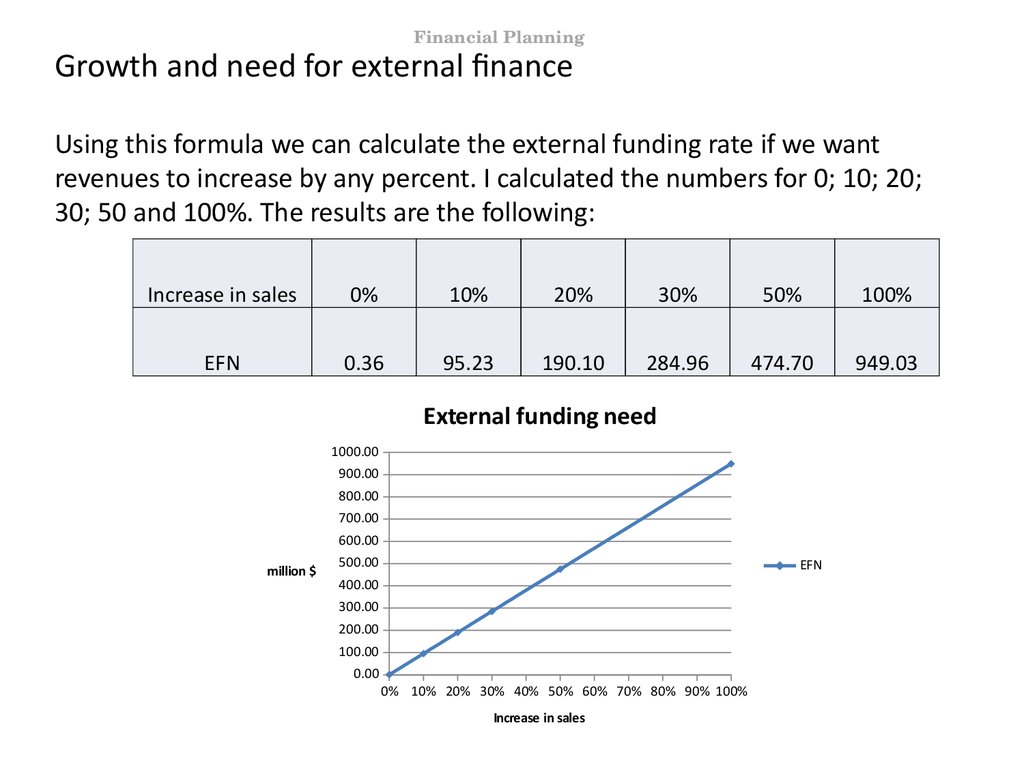

Financial PlanningGrowth and need for external finance

Using this formula we can calculate the external funding rate if we want

revenues to increase by any percent. I calculated the numbers for 0; 10; 20;

30; 50 and 100%. The results are the following:

Increase in sales

0%

10%

20%

30%

50%

100%

EFN

0.36

95.23

190.10

284.96

474.70

949.03

External funding need

1000.00

900.00

800.00

700.00

600.00

million $

500.00

EFN

400.00

300.00

200.00

100.00

0.00

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Increase in sales

40. 40. dia

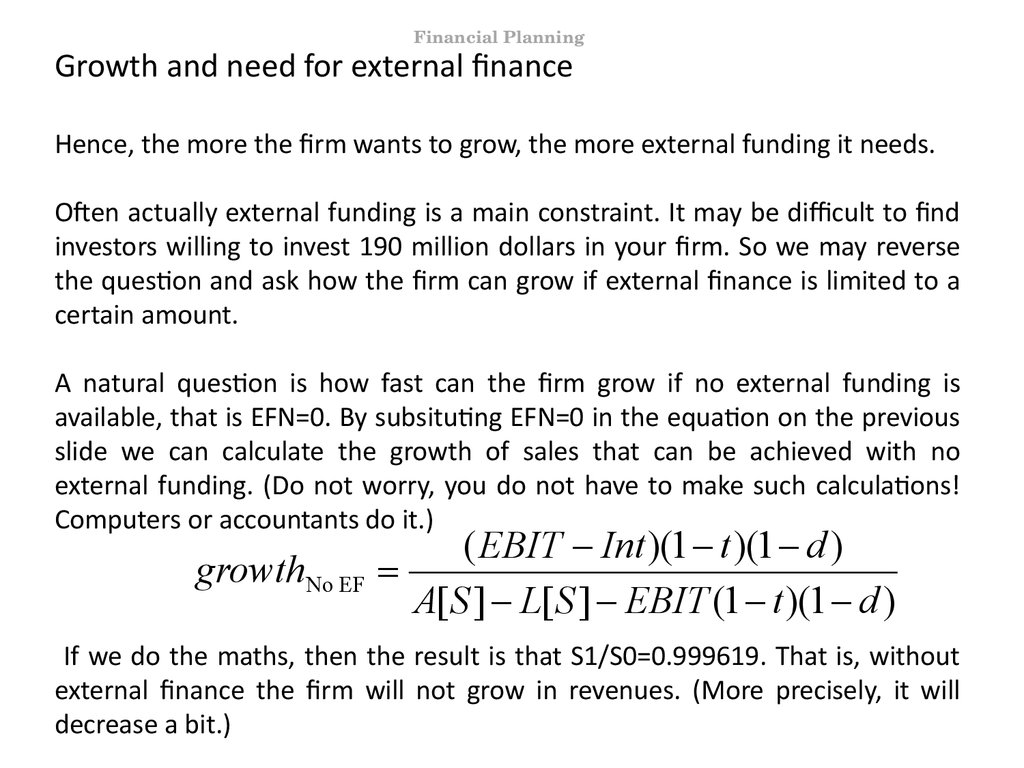

Financial PlanningGrowth and need for external finance

Hence, the more the firm wants to grow, the more external funding it needs.

Often actually external funding is a main constraint. It may be difficult to find

investors willing to invest 190 million dollars in your firm. So we may reverse

the question and ask how the firm can grow if external finance is limited to a

certain amount.

A natural question is how fast can the firm grow if no external funding is

available, that is EFN=0. By subsituting EFN=0 in the equation on the previous

slide we can calculate the growth of sales that can be achieved with no

external funding. (Do not worry, you do not have to make such calculations!

Computers or accountants do it.)

growth No EF

( EBIT Int )(1 t )(1 d )

A[ S ] L[ S ] EBIT (1 t )(1 d )

If we do the maths, then the result is that S1/S0=0.999619. That is, without

external finance the firm will not grow in revenues. (More precisely, it will

decrease a bit.)

41. 41. dia

Financial PlanningSustainable rate of growth

The sustainable growth rate is a measure of how much a firm can grow

without borrowing more money. After the firm has passed this rate, it must

borrow

funds

from

another

source

to

facilitate

growth.

If there is no external finance, then the growth of the shareholders’ equity

constrains the growth of the firm. The growth of the equity is the amount of

profits not paid out to the shareholders.

The numerator of the previous formula is the earning (profit) of the firm once

interest expenses, taxes and dividend have been paid. This is the amount that

the shareholders equity is increasing. The higher is this amount, the more can

the firm grow.

The growth of the shareholders equity is determined by how profitably the

firm uses the equity which is measured by the return on equity (RoE). Hence,

the higher is RoE, the higher is the growth of the shareholders equity and in

turn the higher is the sustainable rate of growth.

42. 42. dia

Financial PlanningSustainable rate of growth

There is an easy formula to calculate sustainable growth:

Sustainable Rate of Growth = (1-d)*RoE

It just tells that the higher is the RoE (and hence the profits) and the higher

share of that profit is retained (that is the smaller d), the more can the firm

grow.

How is the sustainable growth of Manchester United?

In the last two years MU did not pay dividends, so d=0. The RoE of MU equals

-0.18%, so MU can grow without external finance at that rate. We have seen

that actually MU decreased more during 2015 (-9%).

43. 43. dia

Financial PlanningWorking Capital Management

An important part of financial planning and management is working capital

management.

In many instances companies need to spend money on costs before getting

some revenue from selling its product. Generally, you incur costs before the

revenues, e.g. you buy the raw material and ingredients of your product, you

make the product and only afterwards can you sell it.

Working capital measures this difference between short-term assets and

liabilities.

Working capital = Current assets - current liabilities

Remember that current assets are cash and other assets expected to be

converted to cash or consumed in a year. Receivables and inventory is also

part of current assets.

Current liabilities are reasonably expected to be liquidated within a year. They

usually include payables such as wages, accounts, taxes.

44. 44. dia

Financial PlanningWorking Capital Management

There is a problem if you have to pay a lot and for a long time before you have

revenues. It is even a problem if the revenues cover the costs. Thus, the big

task of working capital management is to find efficient ways to finance the

working of the company until revenues arrive.

In other words, a company may have a lot of profitable assets, but may be

unable to convert those assets into cash and have financing problems. For

instance, you may sell a lot of your products, but if your clients pay you later,

then you may be short of liquidity. Positive working capital is required to

ensure that a firm is able to continue its operations and that it has sufficient

funds to satisfy both maturing short-term debt and upcoming operational

expenses. The management of working capital involves managing inventories,

accounts receivable and payable, and cash.

Note that if you have a positive working capital, then you expect to have more

current asset (cash, receivables and inventory) than current liabilities (money

that you have to pay within a year) and then there is a good chance that you

will have enough money to settle those bills.

45. 45. dia

Financial PlanningEfficient Management of Working Capital Principle:

Minimize the investment in non-earning assets such as receivables and

inventories. Note that receivables (money that your customers owe you, but

have not paid yet) and inventory (products that you have produced but did

not sell yet) are resources and good for the company, but they need to be

converted into money that you can use to finance your operations. Thus,

regarding current assets a firm has to be careful with the items that are not

directly making money.

Maximizing the use of free credit such as prepayments by customers or

accounts payable. This free credit because for instance an account that is

payable means that you have the product, but you have not paid for it yet. So

you can use it for free.

The two advices help decrease the time between the selling of your product

and the arrival of money for it and therefore they reduce the working capital

need.

The amount of time it takes to turn the net current assets and current

liabilities into cash is called working capital cycle (or cash cycle time).

46. 46. dia

Financial PlanningWorking Capital Management

The longer the working capital cycle is, the longer a business is tying up capital

in its working capital without earning a return on it. Therefore, as already

mentioned companies strive to reduce their working capital cycle by collecting

receivables quicker or sometimes stretching accounts payable.

A positive working capital cycle balances incoming and outgoing payments to

minimize net working capital and maximize free cash flow. For example, a

company that pays its suppliers in 30 days but takes 60 days to collect its

receivables has a working capital cycle of 30 days. This 30 day cycle usually

needs to be funded through some way of funding, for instance a bank credit.

The interest on this financing is a cost that reduces the company's profitability.

Growing businesses require cash, and being able to free up cash by shortening

the working capital cycle is the most inexpensive way to grow.

47. 47. dia

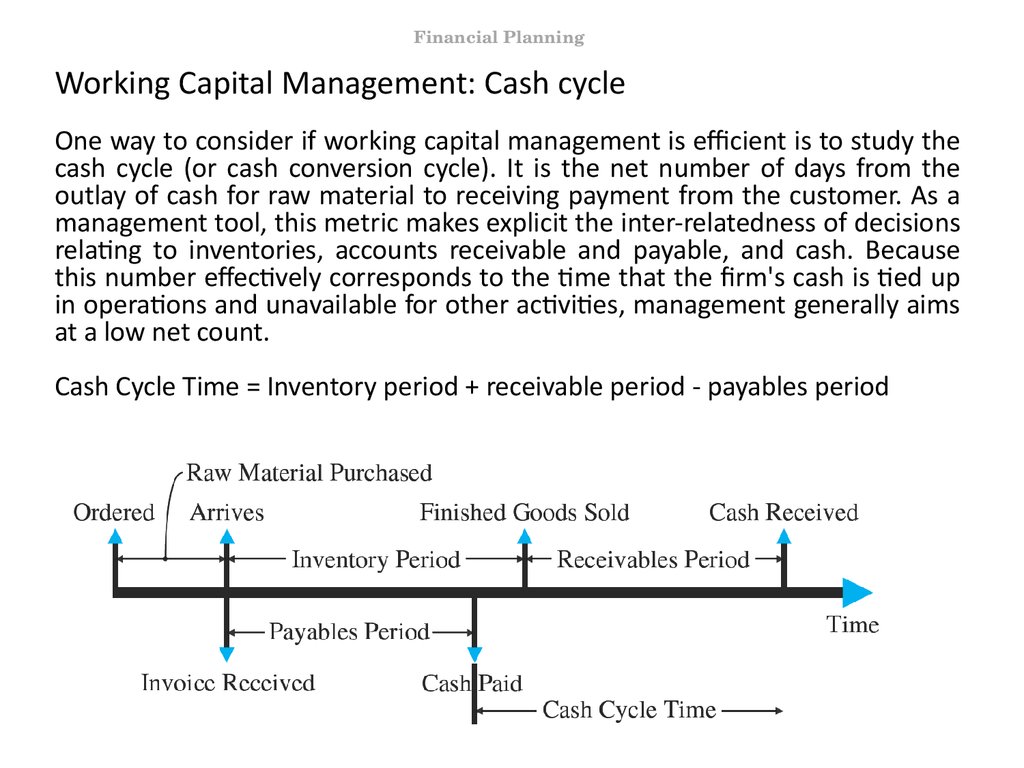

Financial PlanningWorking Capital Management: Cash cycle

One way to consider if working capital management is efficient is to study the

cash cycle (or cash conversion cycle). It is the net number of days from the

outlay of cash for raw material to receiving payment from the customer. As a

management tool, this metric makes explicit the inter-relatedness of decisions

relating to inventories, accounts receivable and payable, and cash. Because

this number effectively corresponds to the time that the firm's cash is tied up

in operations and unavailable for other activities, management generally aims

at a low net count.

Cash Cycle Time = Inventory period + receivable period - payables period

48. 48. dia

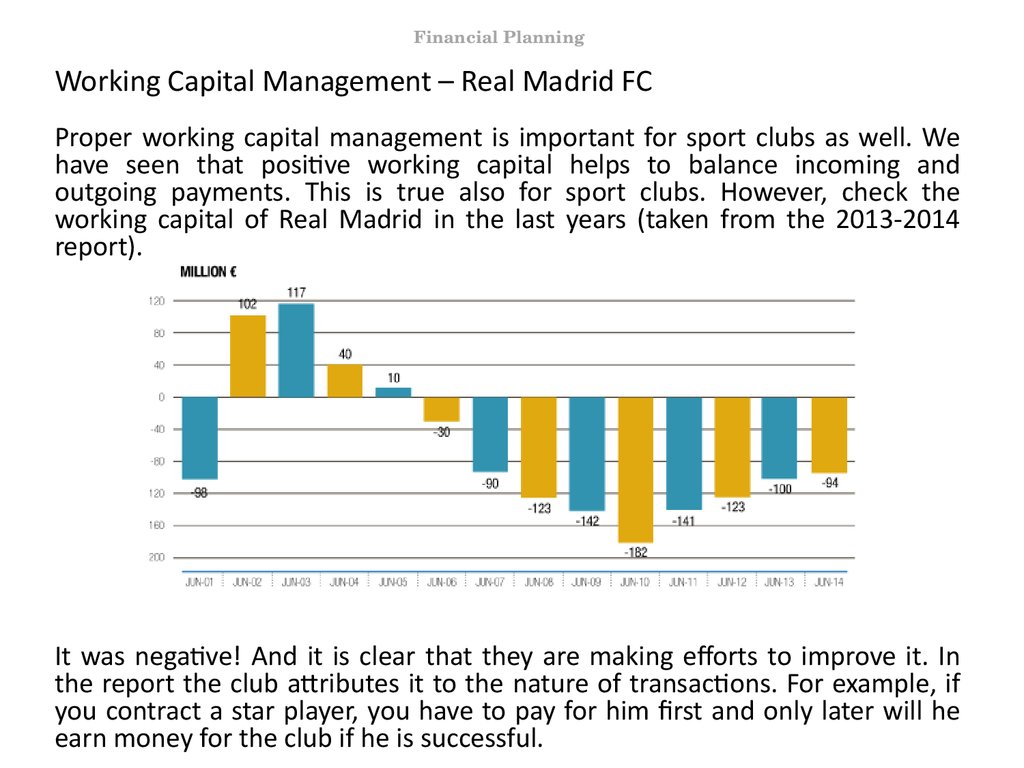

Financial PlanningWorking Capital Management – Real Madrid FC

Proper working capital management is important for sport clubs as well. We

have seen that positive working capital helps to balance incoming and

outgoing payments. This is true also for sport clubs. However, check the

working capital of Real Madrid in the last years (taken from the 2013-2014

report).

It was negative! And it is clear that they are making efforts to improve it. In

the report the club attributes it to the nature of transactions. For example, if

you contract a star player, you have to pay for him first and only later will he

earn money for the club if he is successful.

49. 49. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting

(This section builds heavily on the chapter about working capital in Brealey –

Myers: Principles of Corporate Finance.)

We have seen the importance of working capital management. Concretely, we

have seen that it is of utmost importance to ensure that the company has

always enough money. Cash budgeting is about planning and forecasting

future sources and uses of cash.

These forecasts serve two purposes. First, they alert the financial manager to

future cash needs. Second, the cash-flow forecasts provide a standard, or

budget, against which subsequent performance can be judged.

There are three common steps to preparing a cash budget:

• Step 1. Forecast the sources of cash. The largest inflow of cash comes from

payments by the firm’s customers.

• Step 2. Forecast uses of cash.

• Step 3. Calculate whether the firm is facing a cash shortage or surplus.

50. 50. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting

The financial plan sets out a strategy for investing cash surpluses or

financing any deficit.

We will illustrate these issues by using the example of an imaginary firm called

Dynamic Mattress that sells mattresses. Open the excel Day 2_Cash

budgeting!

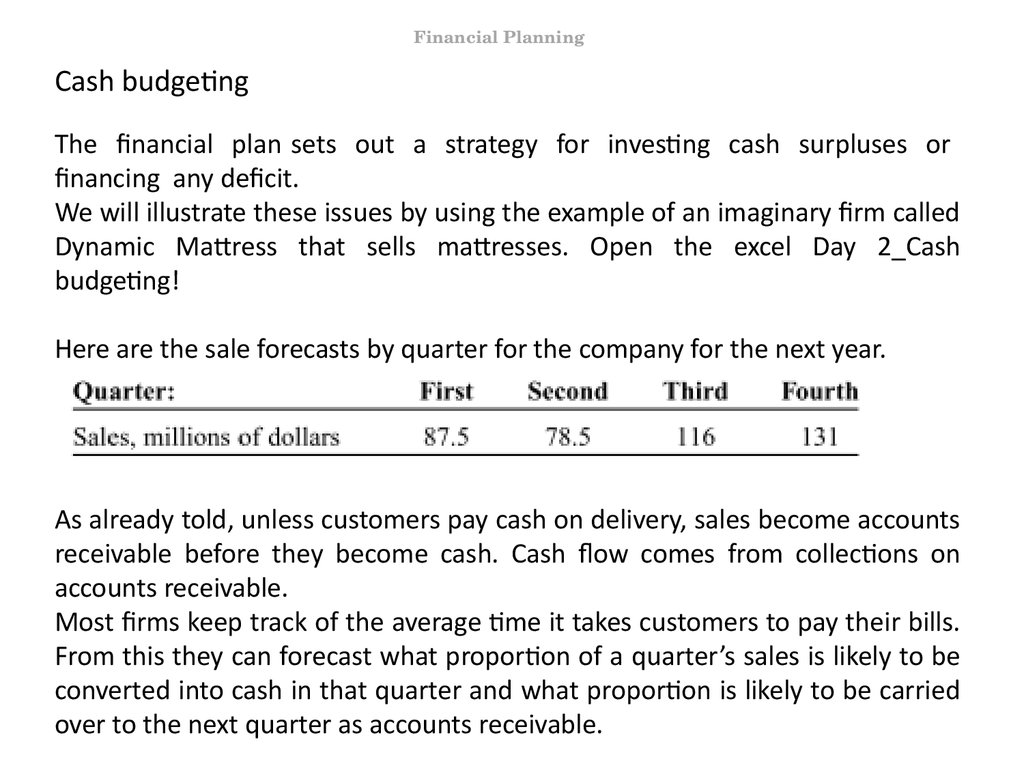

Here are the sale forecasts by quarter for the company for the next year.

As already told, unless customers pay cash on delivery, sales become accounts

receivable before they become cash. Cash flow comes from collections on

accounts receivable.

Most firms keep track of the average time it takes customers to pay their bills.

From this they can forecast what proportion of a quarter’s sales is likely to be

converted into cash in that quarter and what proportion is likely to be carried

over to the next quarter as accounts receivable.

51. 51. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting

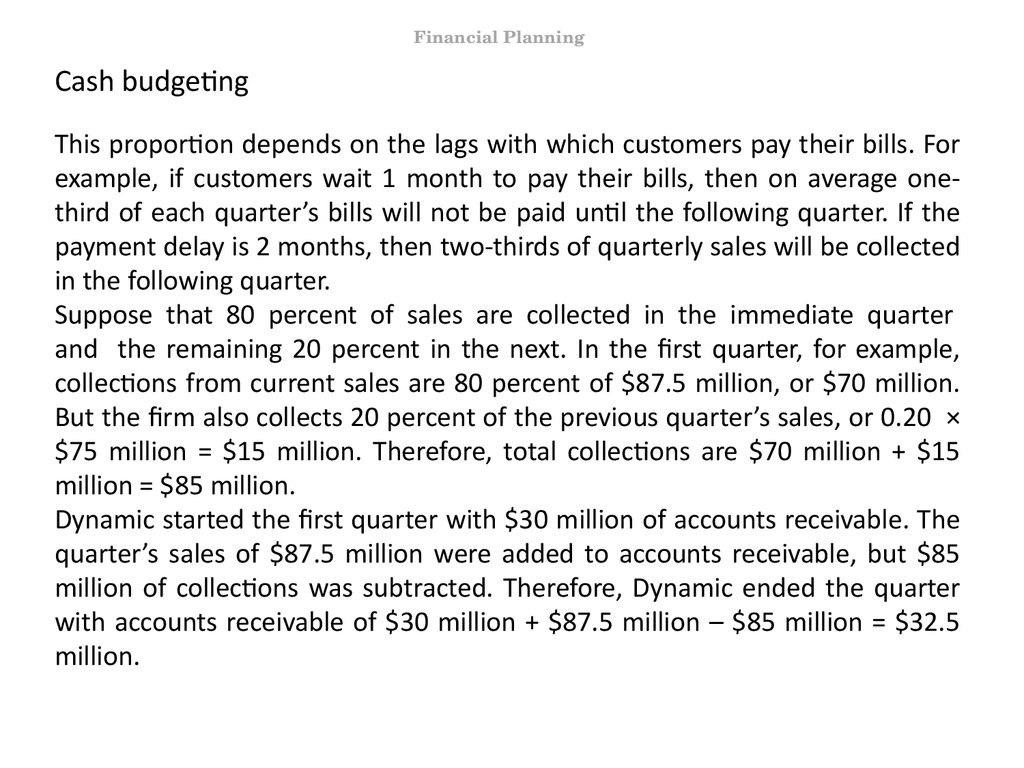

This proportion depends on the lags with which customers pay their bills. For

example, if customers wait 1 month to pay their bills, then on average onethird of each quarter’s bills will not be paid until the following quarter. If the

payment delay is 2 months, then two-thirds of quarterly sales will be collected

in the following quarter.

Suppose that 80 percent of sales are collected in the immediate quarter

and the remaining 20 percent in the next. In the first quarter, for example,

collections from current sales are 80 percent of $87.5 million, or $70 million.

But the firm also collects 20 percent of the previous quarter’s sales, or 0.20 ×

$75 million = $15 million. Therefore, total collections are $70 million + $15

million = $85 million.

Dynamic started the first quarter with $30 million of accounts receivable. The

quarter’s sales of $87.5 million were added to accounts receivable, but $85

million of collections was subtracted. Therefore, Dynamic ended the quarter

with accounts receivable of $30 million + $87.5 million – $85 million = $32.5

million.

52. 52. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Sources of cash

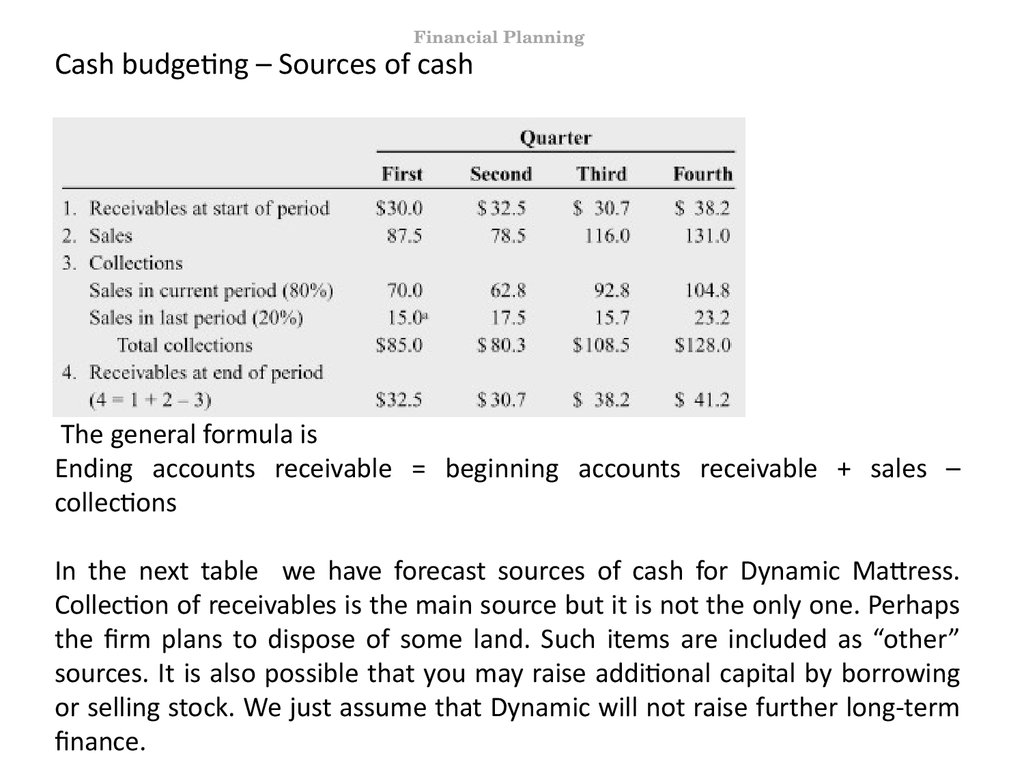

The general formula is

Ending accounts receivable = beginning accounts receivable + sales –

collections

In the next table we have forecast sources of cash for Dynamic Mattress.

Collection of receivables is the main source but it is not the only one. Perhaps

the firm plans to dispose of some land. Such items are included as “other”

sources. It is also possible that you may raise additional capital by borrowing

or selling stock. We just assume that Dynamic will not raise further long-term

finance.

53. 53. dia

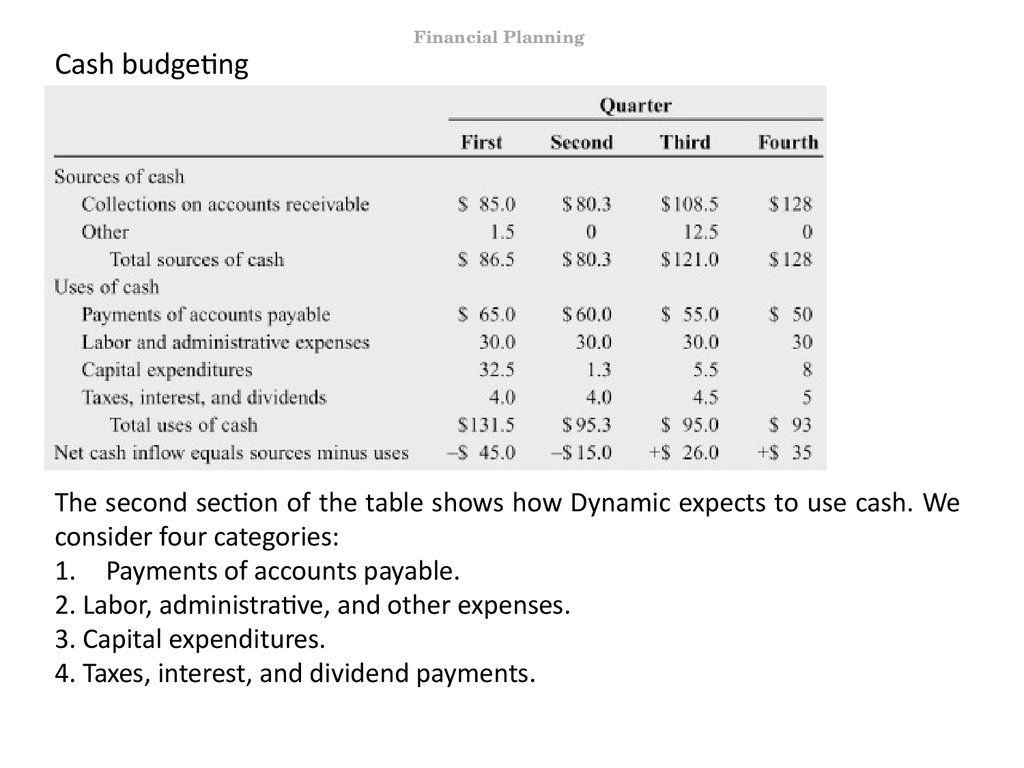

Cash budgetingFinancial Planning

The second section of the table shows how Dynamic expects to use cash. We

consider four categories:

1. Payments of accounts payable.

2. Labor, administrative, and other expenses.

3. Capital expenditures.

4. Taxes, interest, and dividend payments.

54. 54. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Uses of cash

Some details.

1. Payments of accounts payable. Dynamic has to pay its bills for raw

materials, parts, electricity, and so on. The cash-flow forecast assumes all

these bills are paid on time, although Dynamic could probably delay payment

to some extent. Delayed payment is sometimes called stretching your

payables. Stretching is one source of short-term financing, but for most firms

it is an expensive source, because by stretching they lose discounts given to

firms that pay promptly.

2. Labor, administrative, and other expenses. This category includes all other

regular business expenses.

3. Capital expenditures. Note that Dynamic Mattress plans a major outlay of

cash in the first quarter to pay for a long-term asset.

4. Taxes, interest, and dividend payments. This includes interest on currently

outstanding long-term debt and dividend payments to stockholders.

55. 55. dia

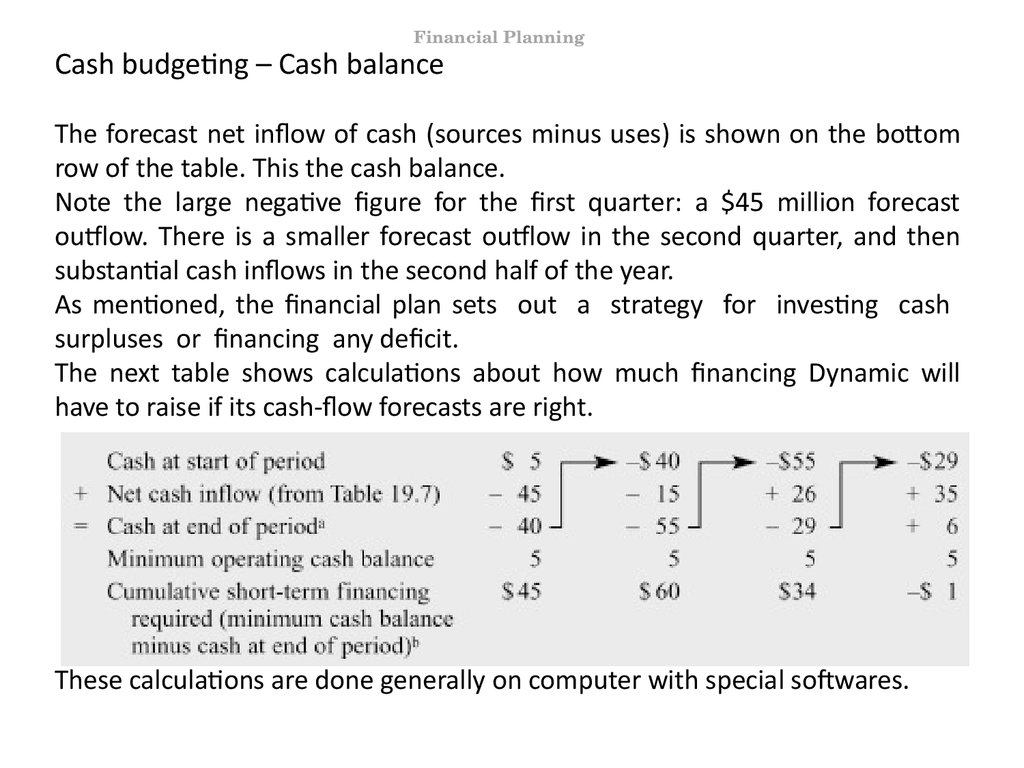

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Cash balance

The forecast net inflow of cash (sources minus uses) is shown on the bottom

row of the table. This the cash balance.

Note the large negative figure for the first quarter: a $45 million forecast

outflow. There is a smaller forecast outflow in the second quarter, and then

substantial cash inflows in the second half of the year.

As mentioned, the financial plan sets out a strategy for investing cash

surpluses or financing any deficit.

The next table shows calculations about how much financing Dynamic will

have to raise if its cash-flow forecasts are right.

These calculations are done generally on computer with special softwares.

56. 56. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Cash balance

Dynamic starts the year with $5 million in cash. There is a $45 million cash

outflow in the first quarter, and so Dynamic will have to obtain at least $45

million – $5 million = $40 million of additional financing. This would leave the

firm with a forecast cash balance of exactly zero at the start of the second

quarter.

Most financial managers regard a planned cash balance of zero as driving too

close to the edge of the cliff. They establish a minimum operating cash

balance to absorb unexpected cash inflows and outflows. We will assume that

Dynamic’s minimum operating cash balance is $5 million. That means it will

have to raise $45 million instead of $40 million in the first quarter, and $15

million more in the second quarter. Thus its cumulative financing requirement

is $60 million in the second quarter. Fortunately, this is the peak; the

cumulative requirement declines in the third quarter when its $26 million net

cash inflow reduces its cumulative financing requirement to $34 million. In the

final quarter Dynamic is out of the woods. Its $35 million net cash inflow is

enough to eliminate short-term financing and actually increase cash balances

above the $5 million minimum acceptable balance.

57. 57. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Cash balance

Some remarks.

• The large cash outflows in the first two quarters do not necessarily spell

trouble for Dynamic Mattress. In part they reflect the capital investment made

in the first quarter: Dynamic is spending $32.5 million. The cash outflows also

reflect low sales in the first half of the year; sales recover in the second half. If

this is a predictable seasonal pattern, the firm should have no trouble

borrowing to help it get through the slow months. Note that this happens also

with sport clubs. For example, upfront collection of membership dues/season

passes means that a large portion of revenues comes in at a certain period of

the year and not spread out during the whole year. Or new players are

contracted also at a certain point in the year, meaning a big cash-outflow.

• In the table we use only a best guess about future cash flows. It is a good

idea to think about the uncertainty in your estimates. For example, you could

undertake a sensitivity analysis, in which you inspect how Dynamic’s cash

requirements would be affected by a shortfall in sales or by a delay in

collections.

58. 58. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Short-term financing plan

Our next step will be to develop a short-term financing plan that covers the

forecast requirements in the most economical way possible.

There are several options for short-term financing. Dynamic may consider

putting off paying its bills and thus increasing its accounts payable. In effect,

this is taking a loan from its suppliers. The financial manager believes that

Dynamic can defer the following amounts in each quarter:

That is, $52 million can be saved in the first quarter by not paying bills in that

quarter. If deferred, these payments must be made in the second quarter.

Similarly, $48 million of the second quarter’s bills can be deferred to the third

quarter and so on. Stretching payables is often costly, however, even if no ill

will is incurred. This is because many suppliers offer discounts for prompt

payment, so that Dynamic loses the discount if it pays late. Assume the lost

discount is 5 percent of the amount deferred. In other words, if a $52 million

payment is delayed in the first quarter, the firm must pay 5 percent more, or

$54.6 million in the next quarter. This is like borrowing at an annual interest

rate of over 20 percent (1.05 4 – 1 = .216, or 21.6%).

59. 59. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Short-term financing plan

Alternatively, Dynamic can borrow up to $40 million from the bank at an

interest cost of 8 percent per year or 2 percent per quarter.

With these two options, the short-term financing strategy is obvious: use the

lower cost bank loan first. Stretch payables only if you can’t borrow enough

from the bank.

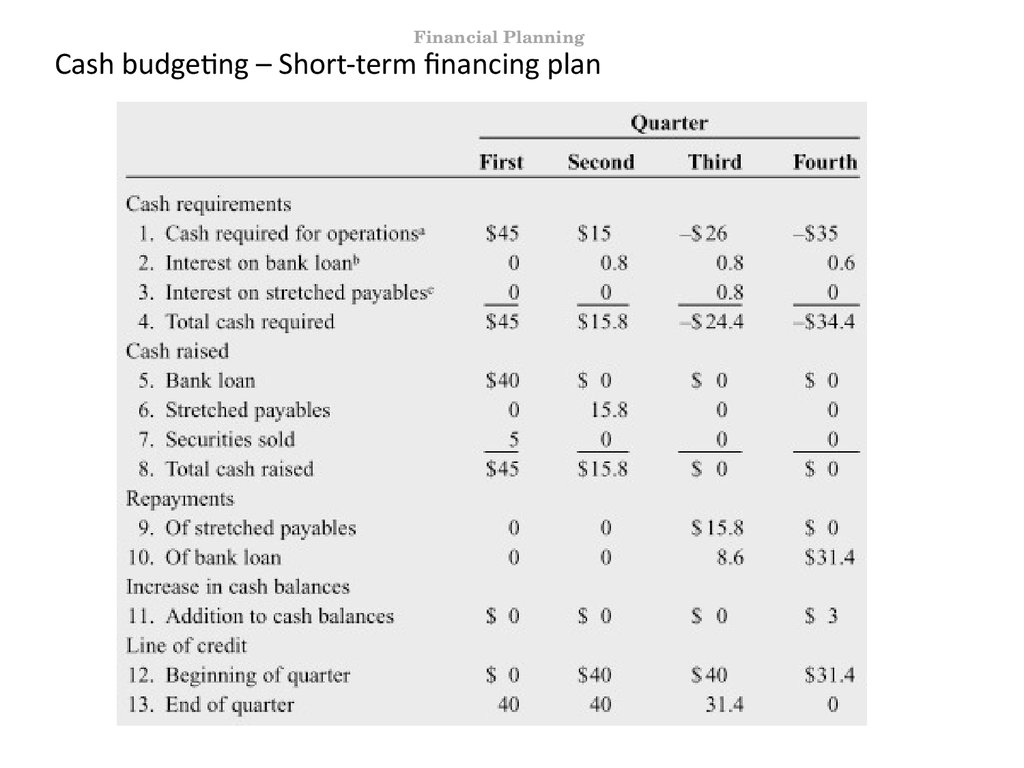

The next table shows the resulting plan. The first panel (cash requirements)

sets out the cash that needs to be raised in each quarter. The second panel

(cash raised) describes the various sources of financing the firm plans to use.

The third and fourth panels describe how the firm will use net cash inflows

when they turn positive.

60. 60. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Short-term financing plan

61. 61. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Short-term financing plan

In the first quarter the plan calls for borrowing the full amount available from

the bank ($40 million). In addition, the firm sells the $5 million of marketable

securities it held at the end of the last year. Thus under this plan it raises the

necessary $45 million in the first quarter.

In the second quarter, an additional $15 million must be raised to cover the

net cash outflow predicted earlier. In addition, $0.8 million must be raised to

pay interest on the bank loan. Therefore, the plan calls for Dynamic to

maintain its bank borrowing and to stretch $15.8 million in payables. Notice

that in the first two quarters, when net cash flow from operations is negative,

the firm maintains its cash balance at the minimum acceptable level.

Additions to cash balances are zero. Similarly, repayments of outstanding

debt are zero. In fact outstanding debt rises in each of these quarters.

In the third and fourth quarters, the firm generates a cash-flow surplus, so the

plan calls for Dynamic to pay off its debt. First it pays off stretched payables, as

it is required to do, and then it uses any remaining cash-flow surplus to pay

down its bank loan. In the third quarter, all of the net cash inflow is used to

reduce outstanding short-term borrowing. In the fourth quarter, the firm pays

off its remaining short-term borrowing and uses the extra $3 million to

increase its cash balances.

62. 62. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Evaluation of the plan

Does the plan solve Dynamic’s short-term financing problem? The plan is

feasible, but Dynamic can probably do better. The most glaring weakness of

this plan is its reliance on stretching payables, an extremely expensive

financing device. Remember that it costs Dynamic 5 percent per quarter to

delay paying bills—20 percent per year at simple interest. This first plan

should merely stimulate the financial manager to search for cheaper sources

of short-term borrowing.

The financial manager would ask several other questions as well. For example:

1. Does Dynamic need a larger reserve of cash or marketable securities

to guard against, say, its customers stretching their payables (thus slowing

down collections on accounts receivable)?

2. Does the plan yield satisfactory current and quick ratios? Its bankers may be

worried if these ratios deteriorate.

3. Are there hidden costs to stretching payables? Will suppliers begin to doubt

Dynamic’s creditworthiness?

63. 63. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Evaluation of the plan

4. Should Dynamic try to arrange long-term financing for the major capital

expenditure in the first quarter? This seems sensible, following the rule of

thumb that long-term assets deserve long-term financing. It would also

dramatically reduce the need for short-term borrowing.

5. Perhaps the firm’s operating and investment plans can be adjusted to make

the short-term financing problem easier. Is there any easy way of deferring the

first quarter’s large cash outflow? For example, suppose that the large capital

investment in the first quarter is for new machinery to be delivered and

installed in the first half of the year. The new machines are not scheduled to

be ready for full-scale use until August. Perhaps the machine manufacturer

could be persuaded to accept 60 percent of the purchase price on delivery

and 40 percent when the machines are installed and operating satisfactorily.

64. 64. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Evaluation of the plan

4. Should Dynamic try to arrange long-term financing for the major capital

expenditure in the first quarter? This seems sensible, following the rule of

thumb that long-term assets deserve long-term financing. It would also

dramatically reduce the need for short-term borrowing.

5. Perhaps the firm’s operating and investment plans can be adjusted to make

the short-term financing problem easier. Is there any easy way of deferring the

first quarter’s large cash outflow? For example, suppose that the large capital

investment in the first quarter is for new machinery to be delivered and

installed in the first half of the year. The new machines are not scheduled to

be ready for full-scale use until August. Perhaps the machine manufacturer

could be persuaded to accept 60 percent of the purchase price on delivery

and 40 percent when the machines are installed and operating satisfactorily.

Important message: Short-term financing plans must be developed by trial

and error. You lay out one plan, think about it, then try again with different

assumptions on financing and investment alternatives. You continue until you

can think of no further improvements.

65. 65. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Sources of Short-Term Financing: Bank loans

Let us briefly consider alternative ways of short-term borrowing.

Bank loans

The simplest and most common source of short-term finance is an unsecured

loan from a bank. For example, Dynamic might have a standing arrangement

with its bank allowing it to borrow up to $40 million. The firm can borrow and

repay whenever it wants so long as it does not exceed the credit limit. This

kind of arrangement is called a line of credit.

Lines of credit are typically reviewed annually, and it is possible that the bank

may seek to cancel it if the firm’s creditworthiness deteriorates. If the firm

wants to be sure that it will be able to borrow, it can enter into a revolving

credit agreement with the bank. Revolving credit arrangements usually last for

a few years and formally commit the bank to lending up to the agreed limit. In

return the bank will require the firm to pay a commitment fee of around 0.25

percent on any unused amount.

Most bank loans have durations of only a few months. For example,

Dynamic may need a loan to cover a seasonal increase in inventories, and the

loan is then repaid as the goods are sold.

66. 66. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Sources of Short-Term Financing: Bank loans

However, banks also make term loans, which last for several years. These term

loans sometimes involve huge sums of money, and in this case they may be

parceled out among a syndicate of banks. For example, when Eurotunnel

needed to arrange more than $10 billion of borrowing to construct the tunnel

between Britain and France, a syndicate of more than 200 international banks

combined to provide the cash.

67. 67. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Sources of Short-Term Financing: Commercial Papers

Commercial papers

When banks lend money, they provide two services. They match up would-be

borrowers and lenders and they check that the borrower is likely to repay the

loan. Banks recover the costs of providing these services by charging

borrowers on average a higher interest rate than they pay to lenders. These

services are less necessary for large, well-known companies that regularly

need to raise large amounts of cash. These companies have increasingly found

it profitable to bypass the bank and to sell short-term debt, known as

commercial paper, directly to large investors.

Commercial paper has a maximum maturity of 9 months. Commercial paper is

not secured, but companies generally back their issue of paper by arranging a

special backup line of credit with a bank. This guarantees that they can find

the money to repay the paper, and the risk of default is therefore small.

68. 68. dia

Financial PlanningCash budgeting – Sources of Short-Term Financing: Secured loans

Secured loans

Many short-term loans are unsecured, but sometimes the company may offer

assets as security. Since the bank is lending on a short-term basis, the security

generally consists of liquid assets such as receivables, inventories, or

securities. For example, a firm may decide to borrow short-term money

secured by its accounts receivable. When its customers pay their bills, it can

use the cash collected to repay the loan. Banks will not usually lend the full

value of the assets that are used as security. For example, a firm that puts up

$100,000 of receivables as security may find that the bank is prepared to lend

only $75,000. The safety margin (or haircut, as it is called) is likely to be even

larger in the case of loans that are secured by inventory.

69. 69. dia

Financial PlanningConclusion – Financial planning

Hopefully, after this lesson you are convinced about the importance of

financial planning.

We carried out some simple financial planning. Although they were more

simple than planning in real life, but they contained the elements that you

need to know if you are to make a financial plan.

We have also seen how working capital management and cash budgeting

works. These complement and enhance financial planning and are essential

for the good working of any company.

70. 70. dia

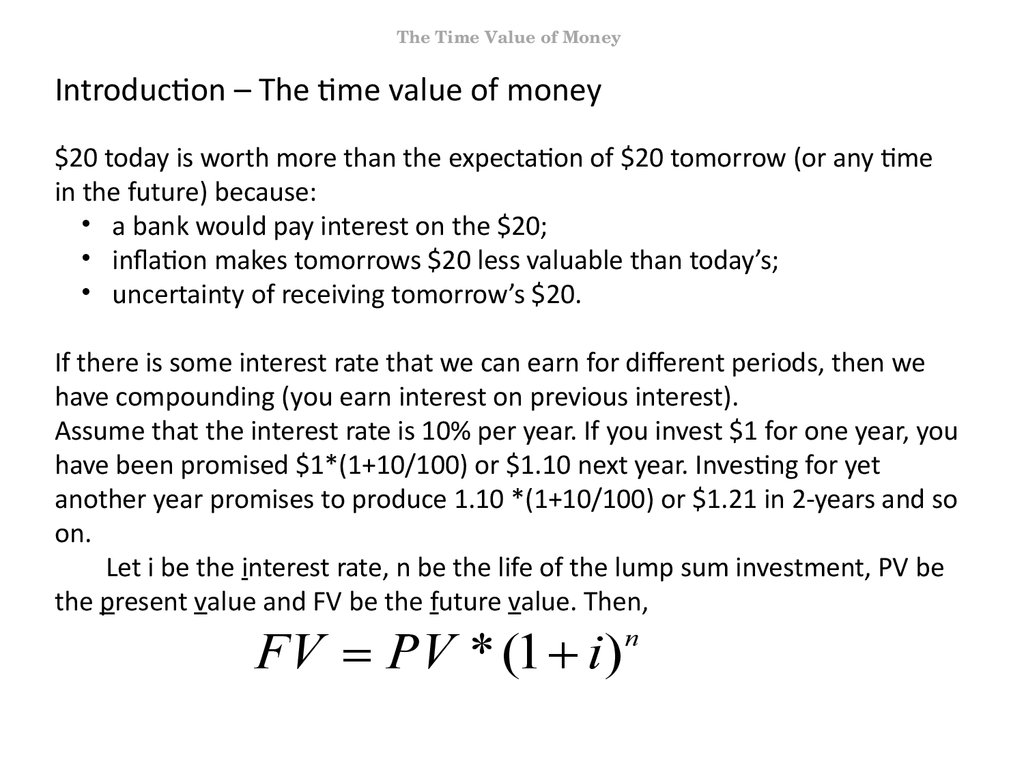

The Time Value of MoneyIntroduction – The time value of money

$20 today is worth more than the expectation of $20 tomorrow (or any time

in the future) because:

• a bank would pay interest on the $20;

• inflation makes tomorrows $20 less valuable than today’s;

• uncertainty of receiving tomorrow’s $20.

If there is some interest rate that we can earn for different periods, then we

have compounding (you earn interest on previous interest).

Assume that the interest rate is 10% per year. If you invest $1 for one year, you

have been promised $1*(1+10/100) or $1.10 next year. Investing for yet

another year promises to produce 1.10 *(1+10/100) or $1.21 in 2-years and so

on.

Let i be the interest rate, n be the life of the lump sum investment, PV be

the present value and FV be the future value. Then,

FV PV * (1 i )

n

71. 71. dia

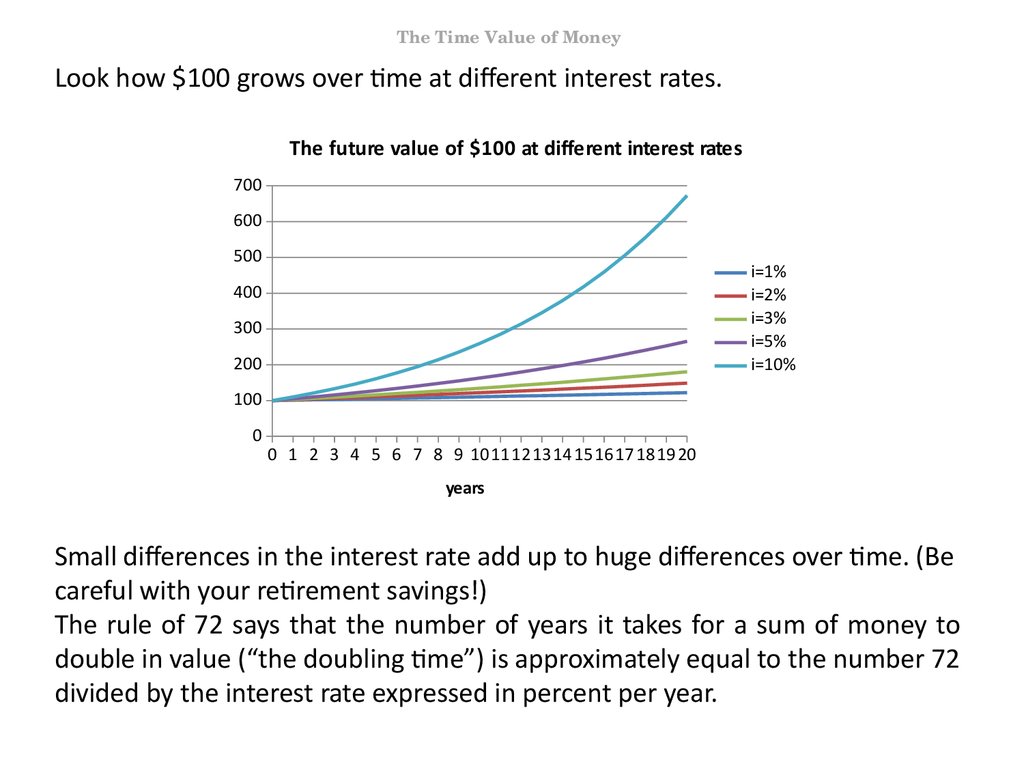

The Time Value of MoneyLook how $100 grows over time at different interest rates.

The future value of $100 at different interest rates

700

600

500

i=1%

i=2%

i=3%

i=5%

i=10%

400

300

200

100

0

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011121314 15 16171819 20

years

Small differences in the interest rate add up to huge differences over time. (Be

careful with your retirement savings!)

The rule of 72 says that the number of years it takes for a sum of money to

double in value (“the doubling time”) is approximately equal to the number 72

divided by the interest rate expressed in percent per year.

72. 72. dia

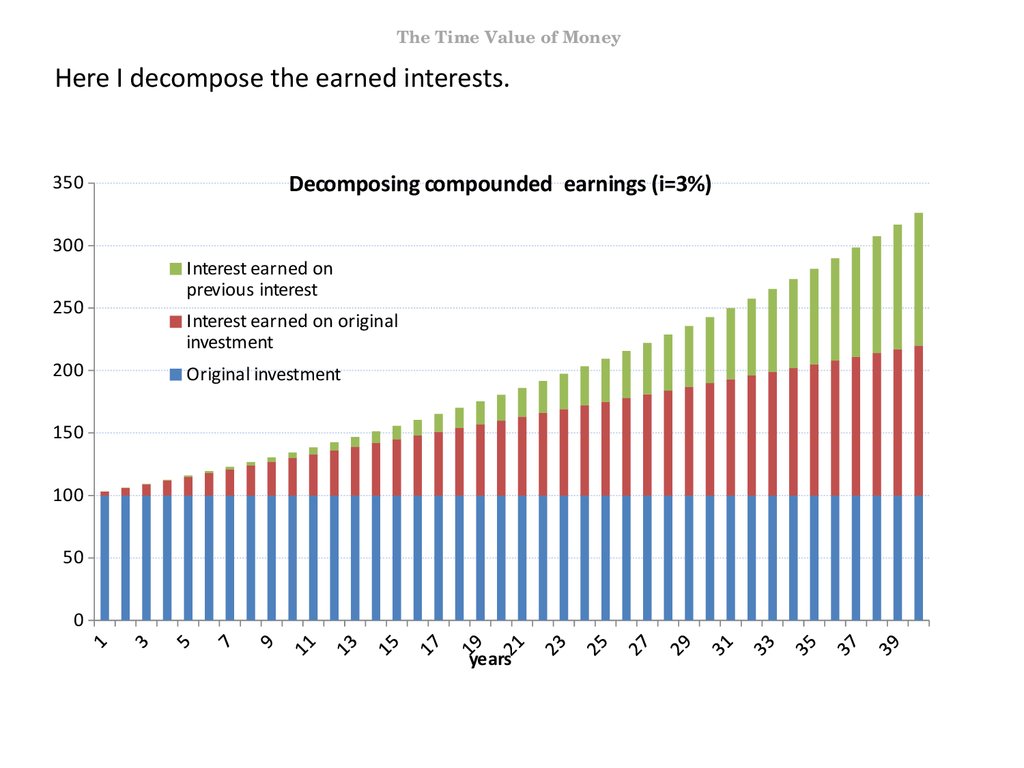

The Time Value of MoneyHere I decompose the earned interests.

350

300

250

200

Decomposing compounded earnings (i=3%)

Interest earned on

previous interest

Interest earned on original

investment

Original investment

150

100

50

0

years

73. The sale of Manhattan Island

The Time Value of MoneyThe sale of Manhattan Island

According to a myth in American history, Peter Minuit, a Dutchman bought the entire

island of Manhattan—where property has averaged $1000+ per square foot over the

last few years— from Native Americans for a measly $24 worth of beads and trinkets

in 1626.

Was it a bad deal?

Depends on how the Native Americans used the proceeds.

If we use a 3% yearly interest rate, then the future value of $24 is $2436289.

If we use a 5% yearly interes rate, then the future value of $ 24 is $4405932902 (over 4

billion dollars).

If we use a 8% yearly interes rate, then the future value of $ 24 is $260301027018004

(over 26 trillion dollars, if am not mistaken).

74. 74. dia

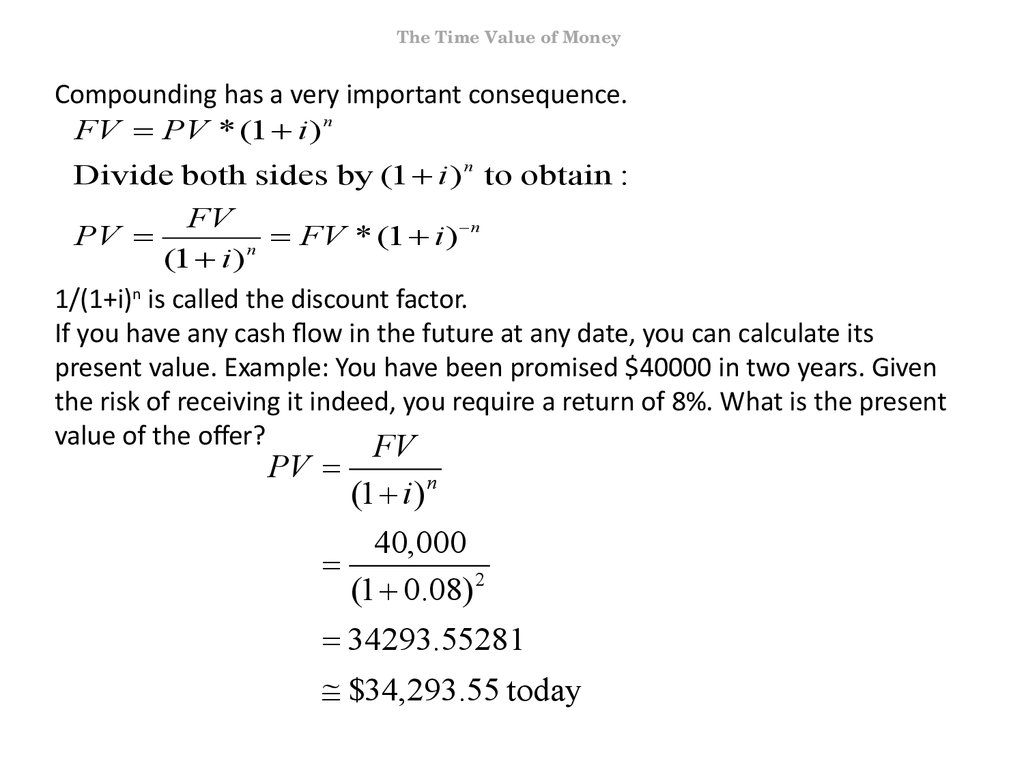

The Time Value of MoneyCompounding has a very important consequence.

FV PV * (1 i ) n

Divide both sides by (1 i ) n to obtain :

FV

n

FV

*

(

1

i

)

(1 i ) n

1/(1+i)n is called the discount factor.

If you have any cash flow in the future at any date, you can calculate its

present value. Example: You have been promised $40000 in two years. Given

the risk of receiving it indeed, you require a return of 8%. What is the present

value of the offer?

FV

PV

PV

(1 i ) n

40,000

(1 0.08) 2

34293.55281

$34,293.55 today

75. 75. dia

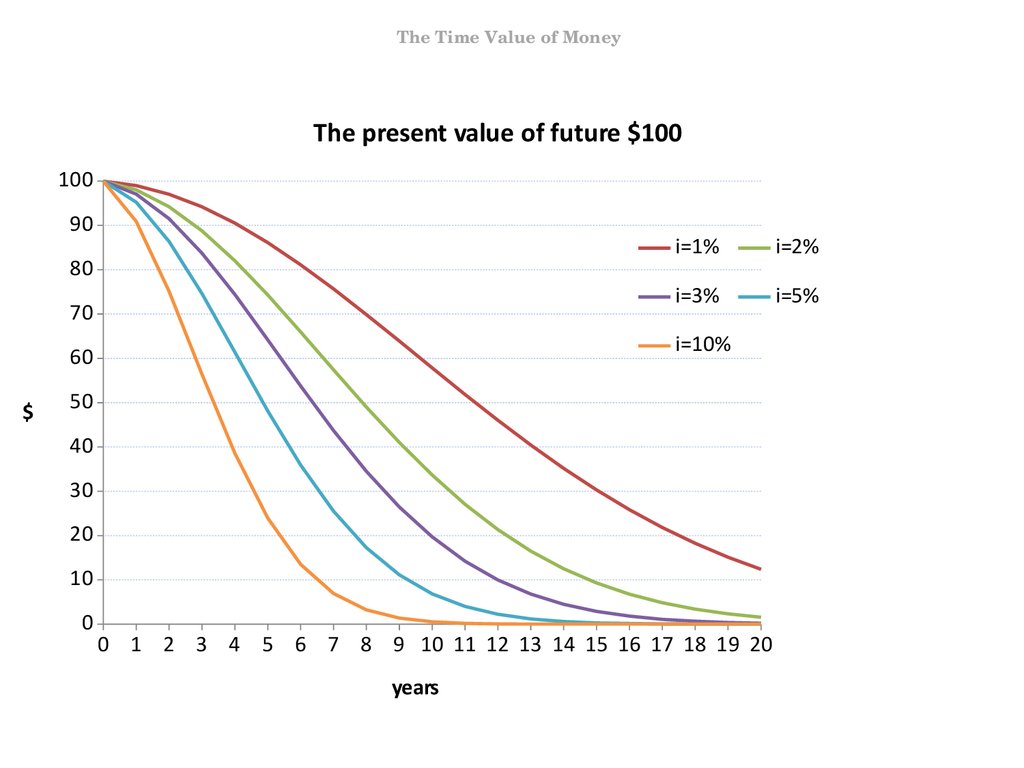

The Time Value of MoneyThe present value of future $100

100

90

80

70

i=2%

i=3%

i=5%

i=10%

60

$

i=1%

50

40

30

20

10

0

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

years

76. 76. dia

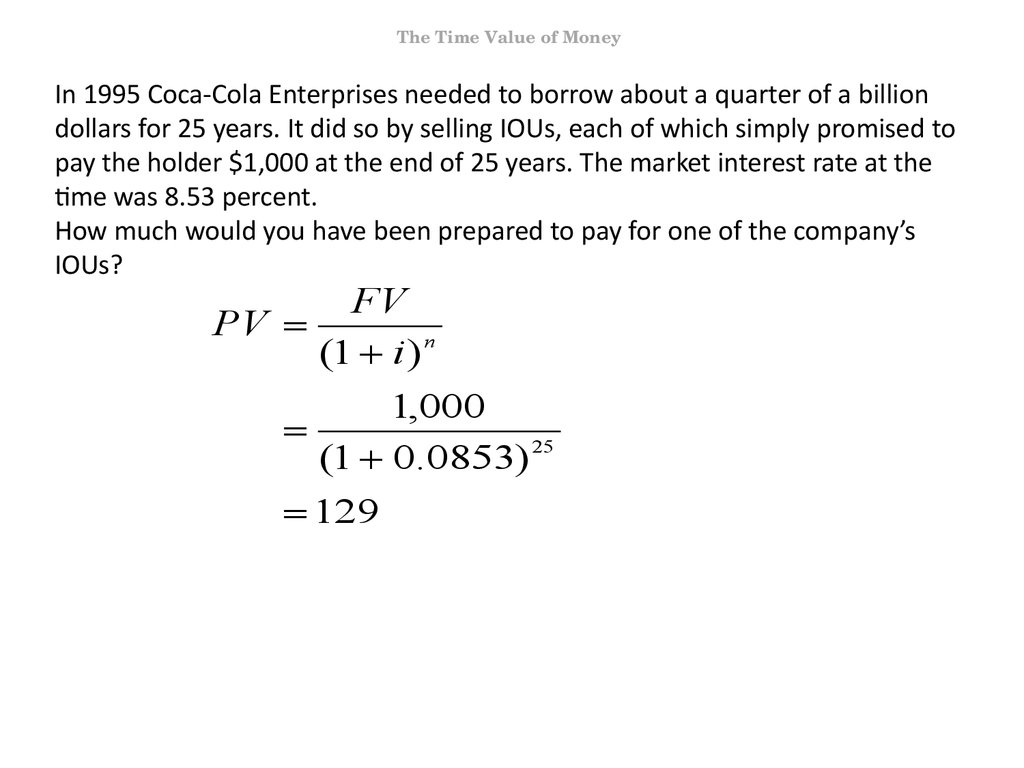

The Time Value of MoneyIn 1995 Coca-Cola Enterprises needed to borrow about a quarter of a billion

dollars for 25 years. It did so by selling IOUs, each of which simply promised to

pay the holder $1,000 at the end of 25 years. The market interest rate at the

time was 8.53 percent.

How much would you have been prepared to pay for one of the company’s

IOUs?

FV

PV

(1 i ) n

1,000

(1 0.0853) 25

129

77. 77. dia

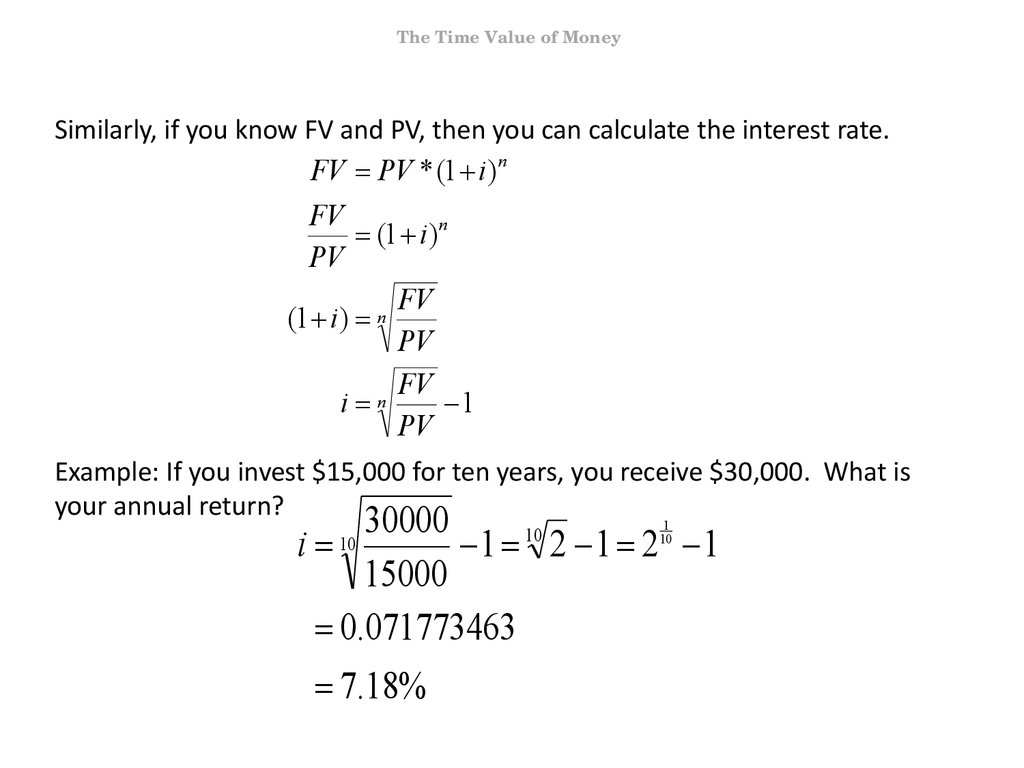

The Time Value of MoneySimilarly, if you know FV and PV, then you can calculate the interest rate.

FV PV * (1 i ) n

FV

(1 i ) n

PV

FV

(1 i ) n

PV

FV

i n

1

PV

Example: If you invest $15,000 for ten years, you receive $30,000. What is

your annual return?

30000

i

1 10 2 1 2 1

15000

0.071773463

7.18%

10

1

10

78. 78. dia

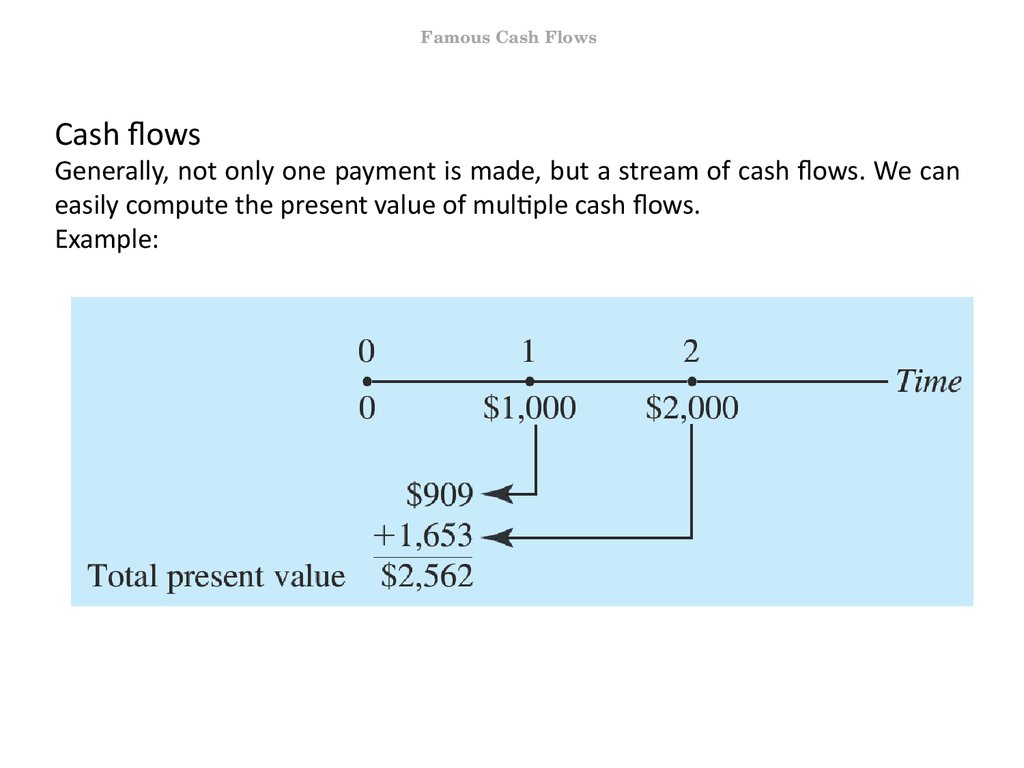

Famous Cash FlowsCash flows

Generally, not only one payment is made, but a stream of cash flows. We can

easily compute the present value of multiple cash flows.

Example:

79. 79. dia

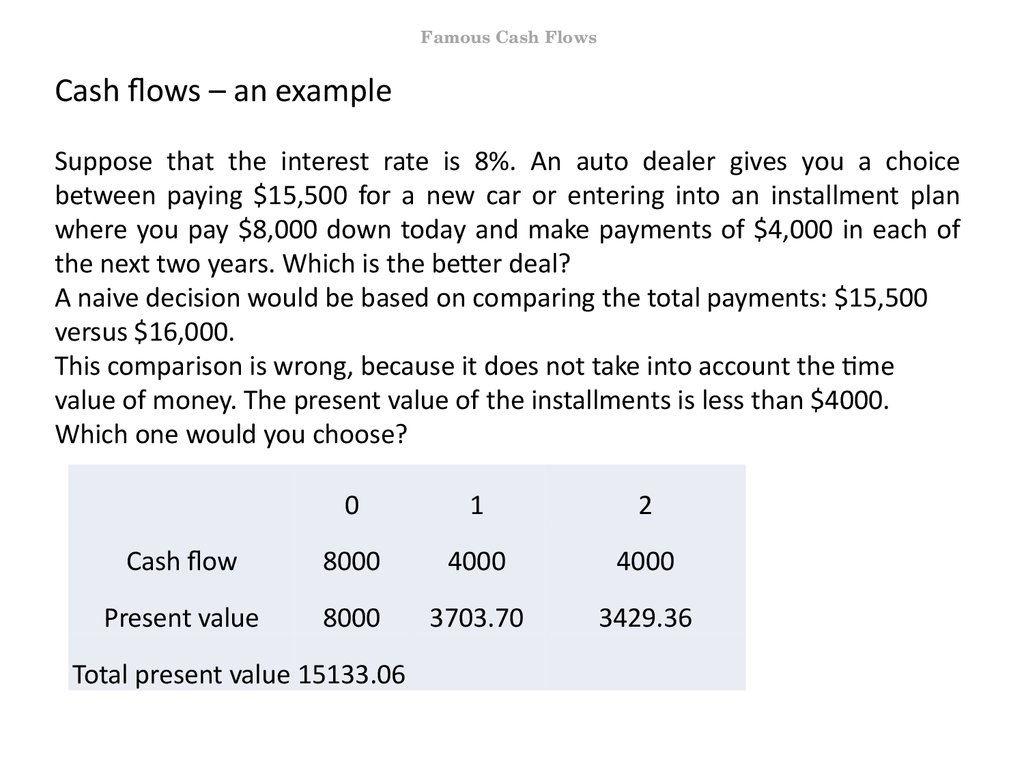

Famous Cash FlowsCash flows – an example

Suppose that the interest rate is 8%. An auto dealer gives you a choice

between paying $15,500 for a new car or entering into an installment plan

where you pay $8,000 down today and make payments of $4,000 in each of

the next two years. Which is the better deal?

A naive decision would be based on comparing the total payments: $15,500

versus $16,000.

This comparison is wrong, because it does not take into account the time

value of money. The present value of the installments is less than $4000.

Which one would you choose?

0

1

2

Cash flow

8000

4000

4000

Present value

8000

3703.70

3429.36

Total present value 15133.06

80. 80. dia

Famous Cash FlowsLevel cash flows

There are cash flows that feature very regular payments.

For example, a home mortgage might require the homeowner to make equal

monthly payments for the life of the loan. For a 30-year loan, this would result

in 360 equal payments.

We will consider now such cash flows. Due to the equal payments, there are

easy formulas to calculate the present value of such cash flows.

81. 81. dia

AnnuityAnnuity

Annuity is a sequence of equally spaced identical cash flows.

We will use the following assumptions:

• the first cash flow will occur exactly one period form now;

• all subsequent cash flows are separated by exactly one period;

• all periods are of equal length;

• the term structure of interest is flat;

• all cash flows have the same (nominal) value.

We will use the following notation:

• PV = the present value of the annuity

• i = interest rate to be earned over the life of the annuity

• n = the number of payments

• pmt = the periodic payment

82. 82. dia

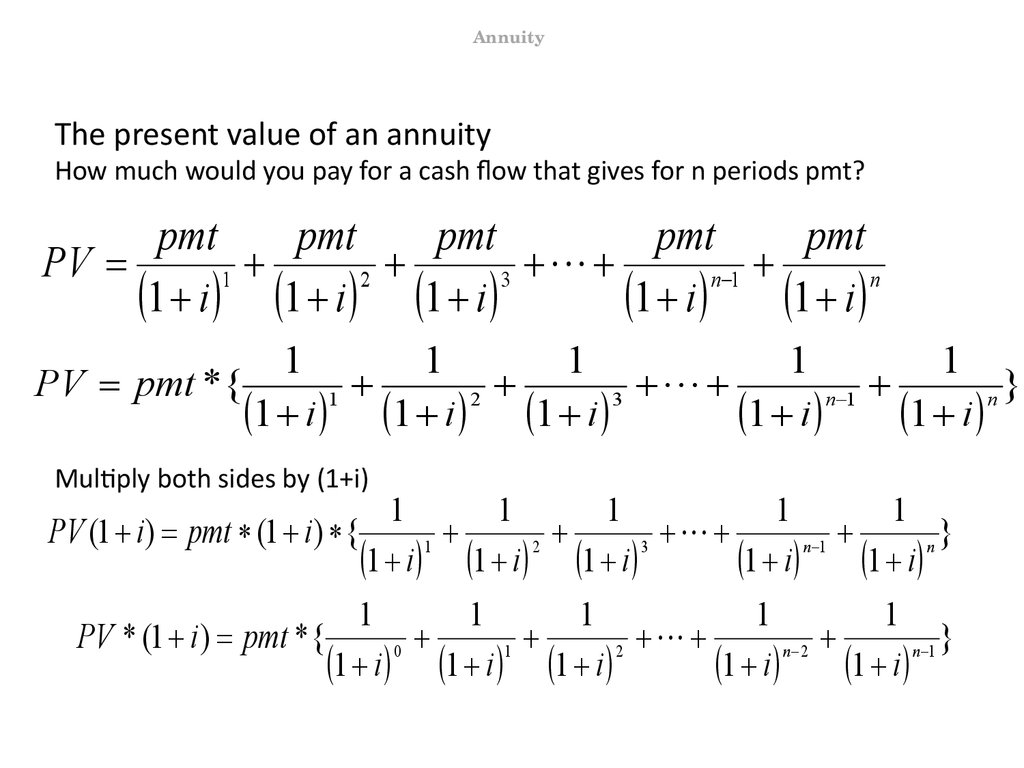

AnnuityThe present value of an annuity

How much would you pay for a cash flow that gives for n periods pmt?

pmt

pmt

pmt

pmt

pmt

PV

1

2

3

n 1

n

1 i 1 i 1 i

1 i 1 i

1

1

1

1

1

PV pmt *{

1

2

3

n 1

n}

1 i 1 i 1 i

1 i

1 i

Multiply both sides by (1+i)

1

1

1

1

1

PV (1 i) pmt (1 i) {

}

1

2

3

n 1

n

1 i 1 i 1 i

1 i 1 i

1

1

1

1

1

PV * (1 i ) pmt * {

}

0

1

2

n 2

n 1

1 i 1 i 1 i

1 i 1 i

83. 83. dia

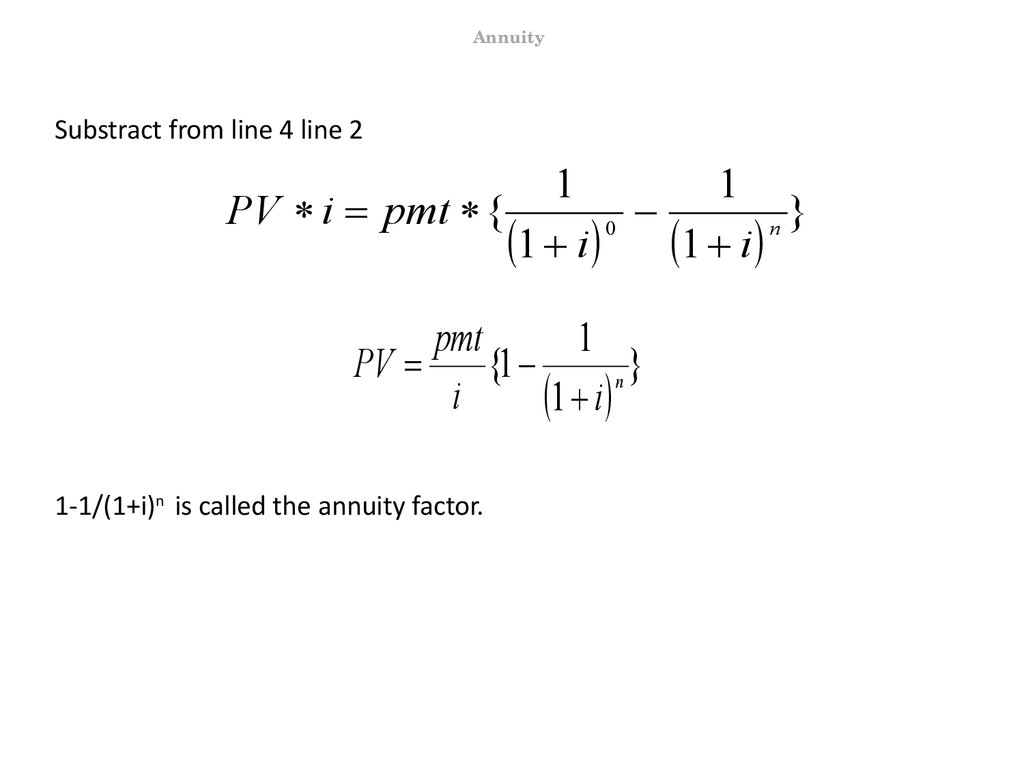

AnnuitySubstract from line 4 line 2

1

1

PV i pmt {

}

0

n

1 i 1 i

pmt

1

PV

{1

}

n

i

1 i

1-1/(1+i)n is called the annuity factor.

84. 84. dia

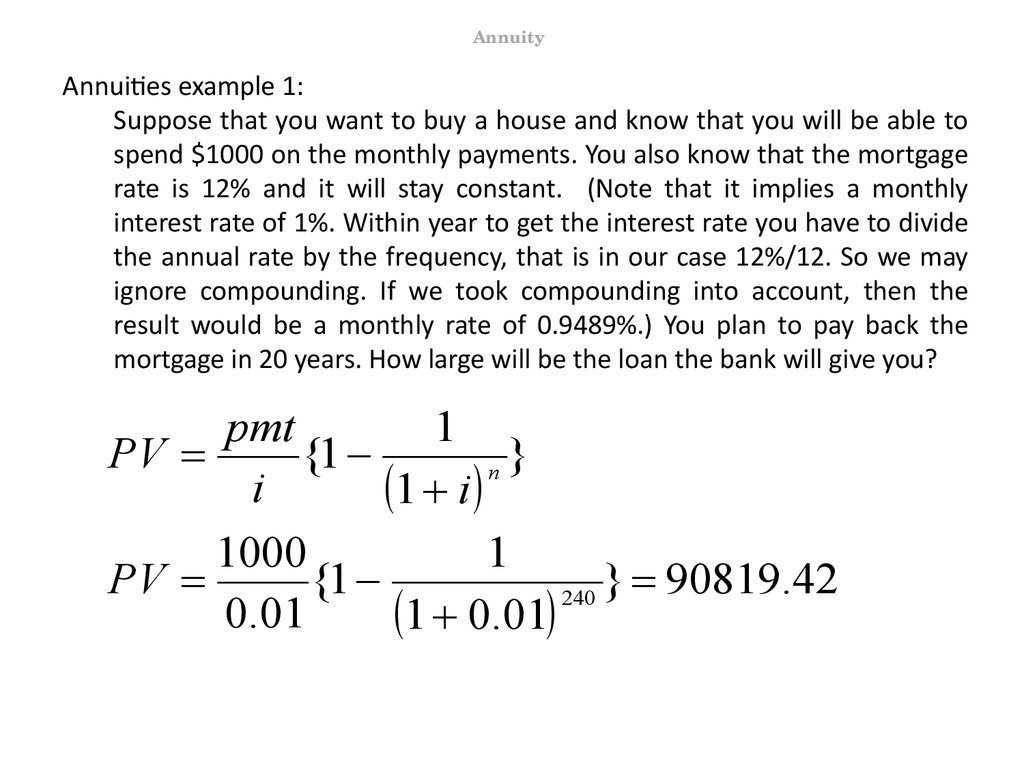

AnnuityAnnuities example 1:

Suppose that you want to buy a house and know that you will be able to

spend $1000 on the monthly payments. You also know that the mortgage

rate is 12% and it will stay constant. (Note that it implies a monthly

interest rate of 1%. Within year to get the interest rate you have to divide

the annual rate by the frequency, that is in our case 12%/12. So we may

ignore compounding. If we took compounding into account, then the

result would be a monthly rate of 0.9489%.) You plan to pay back the

mortgage in 20 years. How large will be the loan the bank will give you?

pmt

1

PV

{1

}

n

i

1 i

1000

1

PV

{1

} 90819.42

240

0.01

1 0.01

85. 85. dia

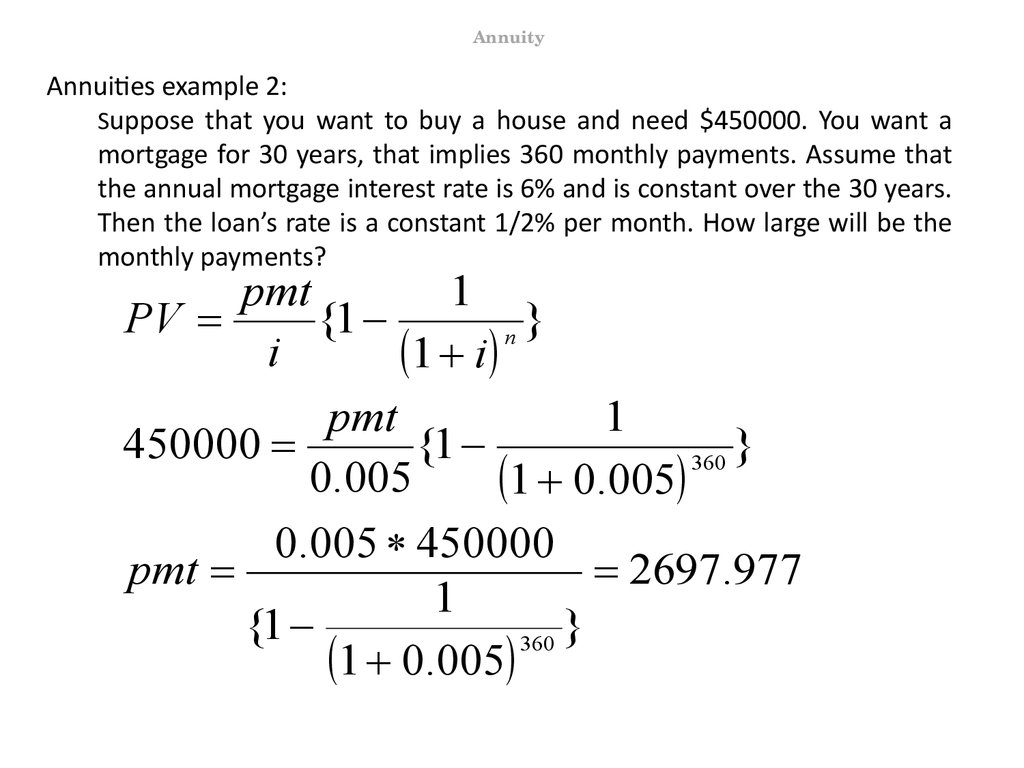

AnnuityAnnuities example 2:

Suppose that you want to buy a house and need $450000. You want a

mortgage for 30 years, that implies 360 monthly payments. Assume that

the annual mortgage interest rate is 6% and is constant over the 30 years.

Then the loan’s rate is a constant 1/2% per month. How large will be the

monthly payments?

pmt

1

PV

{1

}

n

i

1 i

pmt

1

450000

{1

}

360

0.005

1 0.005

0.005 450000

pmt

2697.977

1

{1

}

360

1 0.005

86. 86. dia

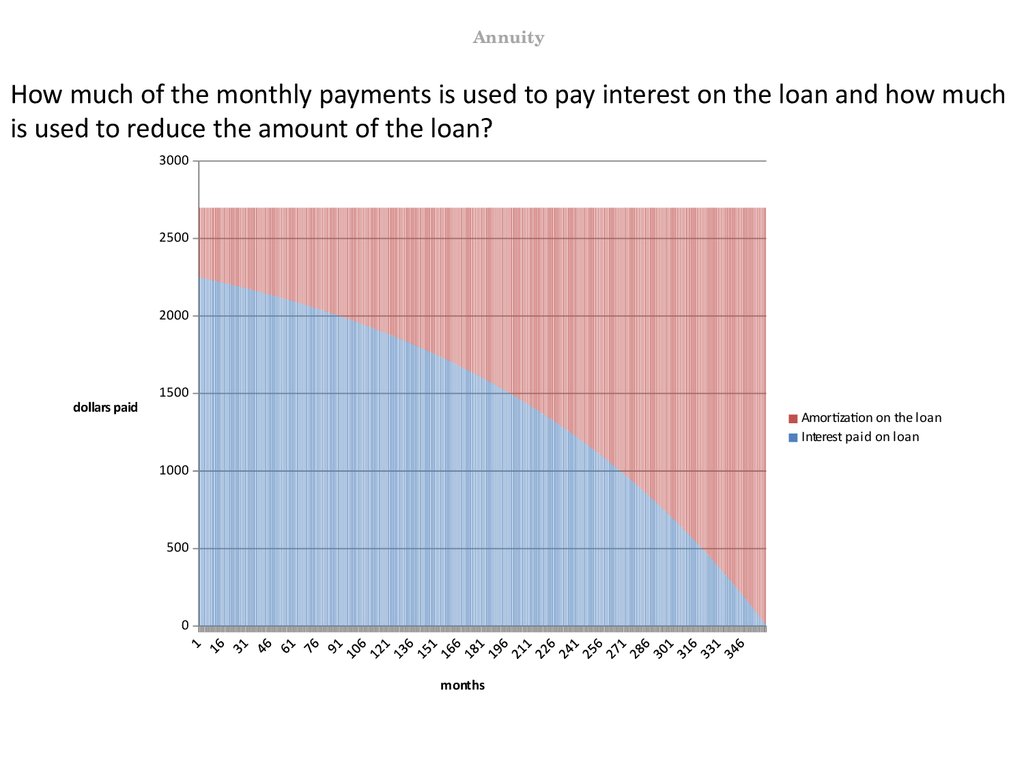

AnnuityHow much of the monthly payments is used to pay interest on the loan and how much

is used to reduce the amount of the loan?

3000

2500

2000

dollars paid

1500

Amortization on the loan

Interest paid on loan

1000

500

0

months

87. 87. dia

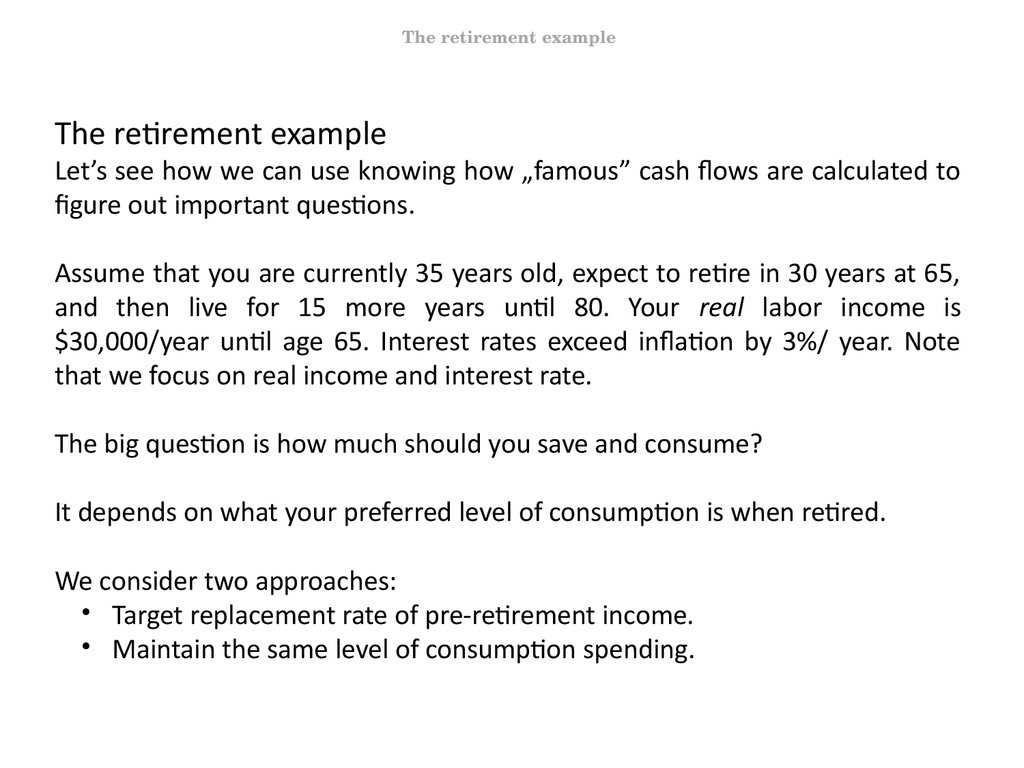

The retirement exampleThe retirement example

Let’s see how we can use knowing how „famous” cash flows are calculated to

figure out important questions.

Assume that you are currently 35 years old, expect to retire in 30 years at 65,

and then live for 15 more years until 80. Your real labor income is

$30,000/year until age 65. Interest rates exceed inflation by 3%/ year. Note

that we focus on real income and interest rate.

The big question is how much should you save and consume?

It depends on what your preferred level of consumption is when retired.

We consider two approaches:

• Target replacement rate of pre-retirement income.

• Maintain the same level of consumption spending.

88. 88. dia

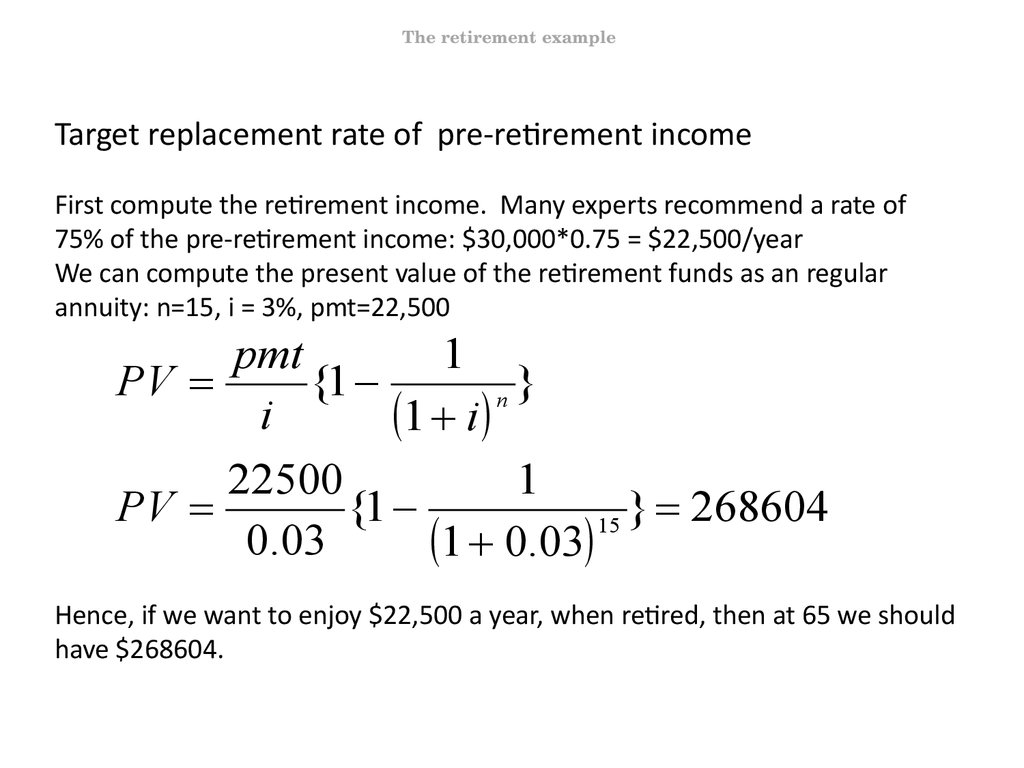

The retirement exampleTarget replacement rate of pre-retirement income

First compute the retirement income. Many experts recommend a rate of

75% of the pre-retirement income: $30,000*0.75 = $22,500/year

We can compute the present value of the retirement funds as an regular

annuity: n=15, i = 3%, pmt=22,500

pmt

1

PV

{1

}

n

i

1 i

22500

1

PV

{1

} 268604

15

0.03

1 0.03

Hence, if we want to enjoy $22,500 a year, when retired, then at 65 we should

have $268604.

89. 89. dia

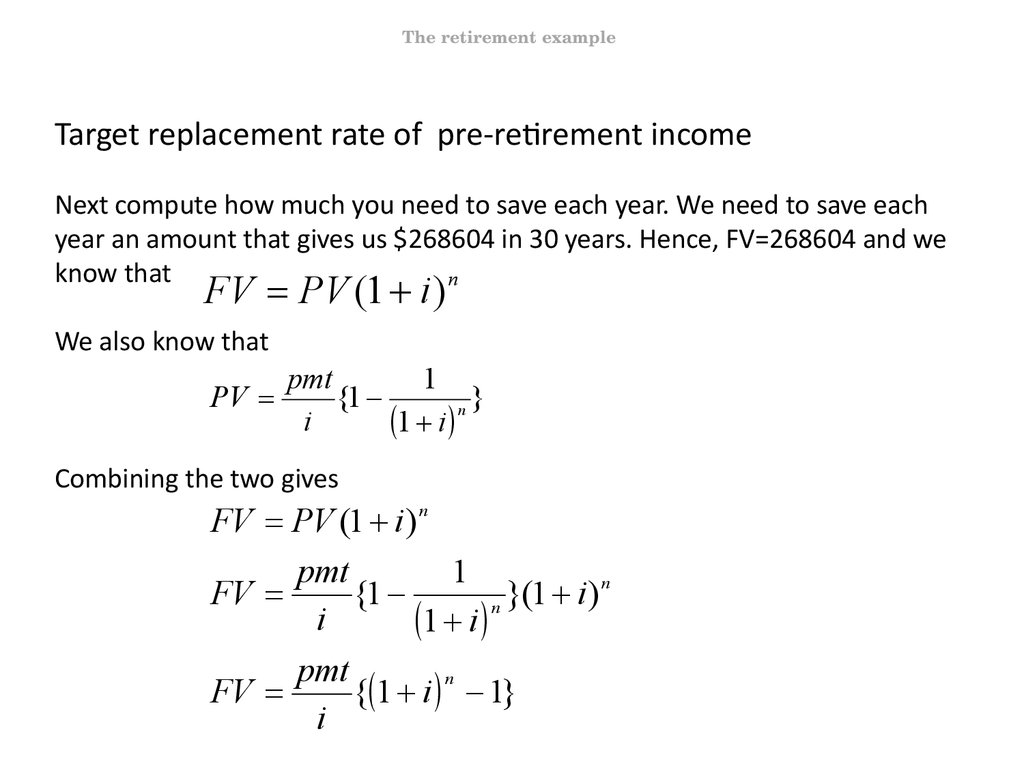

The retirement exampleTarget replacement rate of pre-retirement income

Next compute how much you need to save each year. We need to save each

year an amount that gives us $268604 in 30 years. Hence, FV=268604 and we

know that

n

FV PV (1 i )

We also know that

PV

pmt

1

{1

}

n

i

1 i

Combining the two gives

FV PV (1 i ) n

pmt

1

n

FV

{1

}(

1

i

)

i

1 i n

pmt

n

FV

{ 1 i 1}

i

90. 90. dia

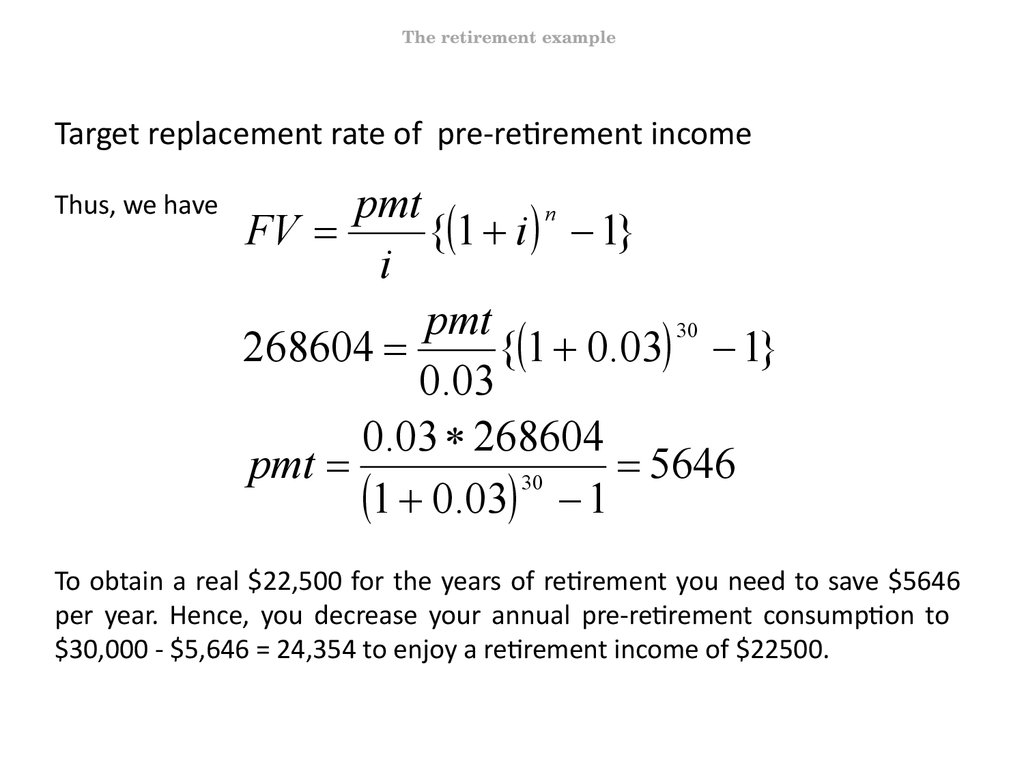

The retirement exampleTarget replacement rate of pre-retirement income

Thus, we have

pmt

n

FV

{ 1 i 1}

i

pmt

30

268604

{ 1 0.03 1}

0.03

0.03 268604

pmt

5646

30

1 0.03 1

To obtain a real $22,500 for the years of retirement you need to save $5646

per year. Hence, you decrease your annual pre-retirement consumption to

$30,000 - $5,646 = 24,354 to enjoy a retirement income of $22500.

91. 91. dia

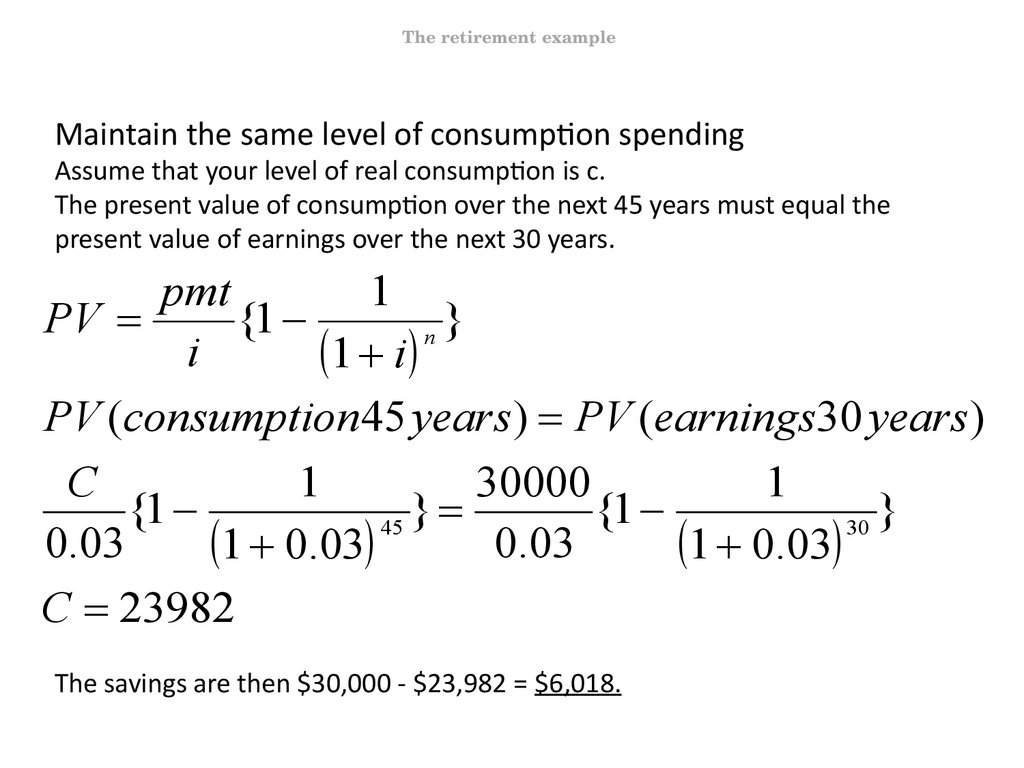

The retirement exampleMaintain the same level of consumption spending

Assume that your level of real consumption is c.

The present value of consumption over the next 45 years must equal the

present value of earnings over the next 30 years.

pmt

1

PV

{1

}

n

i

1 i

PV (consumption 45 years) PV (earnings30 years)

C

1

30000

1

{1

}

{1

}

45

30

0.03

0.03

1 0.03

1 0.03

C 23982

The savings are then $30,000 - $23,982 = $6,018.

92. 92. dia

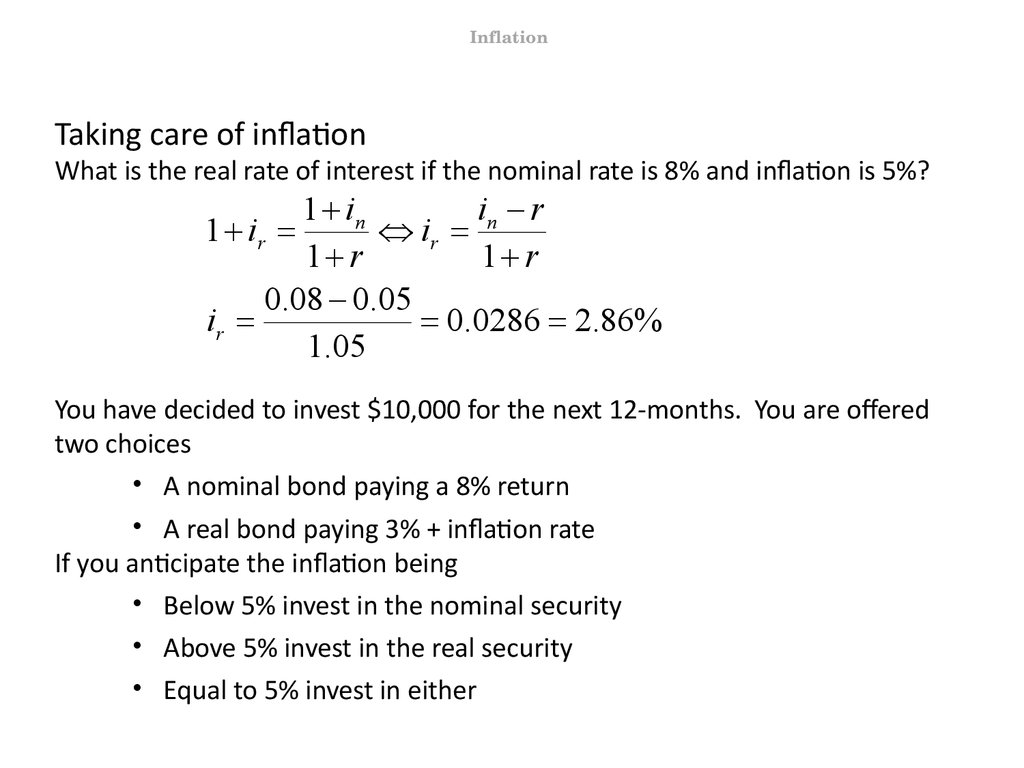

InflationTaking care of inflation

Generally, prices and rates are nominal, that is they are expressed in terms of

currency. But we are interested in real prices and interest rates, that are the

prices and rates expressed in terms of purchasing power. (I do not care really if

a kilo of bread costs $10 or $1, but I am interested how many breads I can buy

using my income.)

The relationship between nominal and real interest rates is the following:

(1 NominalRate) (1 RealRate) * (1 InflationRate)

NominalRate InflationRate

RealRate

1 InflationRate

We will use the notation

In the rate of interest in nominal terms

Ir the rate of interest in real terms

r the rate of inflation

93. 93. dia

InflationTaking care of inflation

What is the real rate of interest if the nominal rate is 8% and inflation is 5%?

1 in

in r

1 ir

ir

1 r

1 r

0.08 0.05

ir

0.0286 2.86%

1.05

You have decided to invest $10,000 for the next 12-months. You are offered

two choices

• A nominal bond paying a 8% return

• A real bond paying 3% + inflation rate

If you anticipate the inflation being

• Below 5% invest in the nominal security

• Above 5% invest in the real security

• Equal to 5% invest in either

94. 94. dia

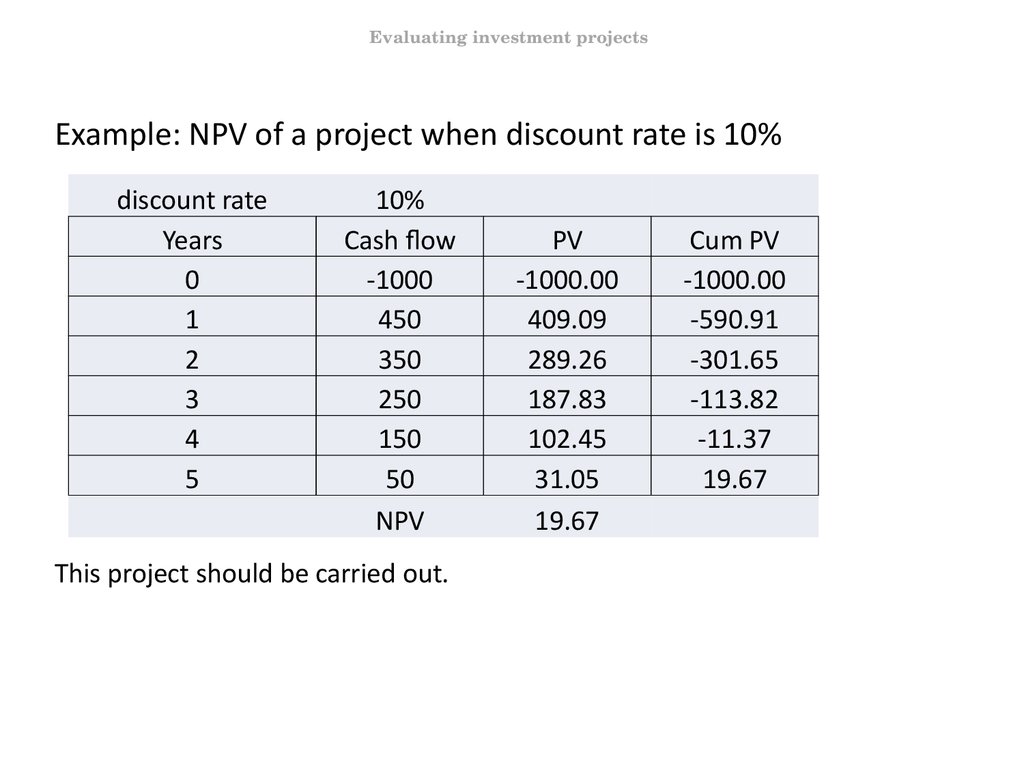

Evaluating investment projectsEvaluating investment opportunities

We can use discounted cash flow analysis to make decisions such as:

• Whether to enter a new line of business

• Whether to invest in equipment to reduce costs

To evaluate investment projects we use the net present value (NPV) rule.

A project’s net present value is the amount by which the project is expected to

increase the wealth of the firm’s current shareholders.

The rule just says: Invest in proposed projects with positive NPV.

NPV = PV – required investment

The following tables show the computation of NPV. To show the affect of the

discount rate, three tables are shown based on different rates

95. 95. dia

Evaluating investment projectsExample: NPV of a project when discount rate is 10%

discount rate

Years

0

1

2

3

4

5

10%

Cash flow

-1000

450

350

250

150

50

NPV

This project should be carried out.

PV

-1000.00

409.09

289.26

187.83

102.45

31.05

19.67

Cum PV

-1000.00

-590.91

-301.65

-113.82

-11.37

19.67

96. 96. dia

Evaluating investment projectsExample: NPV of a project when discount rate is 15%

We consider the same project, but with a different discount rate. (We may

consider the cash flows more risky and expect a higher rate of return.)

discount rate

15%

Years

Cash flow

PV

Cum PV

0

-1000

-1000.00

-1000.00

1

450

391.30

-608.70

2

350

264.65

-344.05

3

250

164.38

-179.67

4

150

85.76

-93.90

5

50

24.86

-69.04

NPV

-69.04

The project should not be carried out.

97. 97. dia

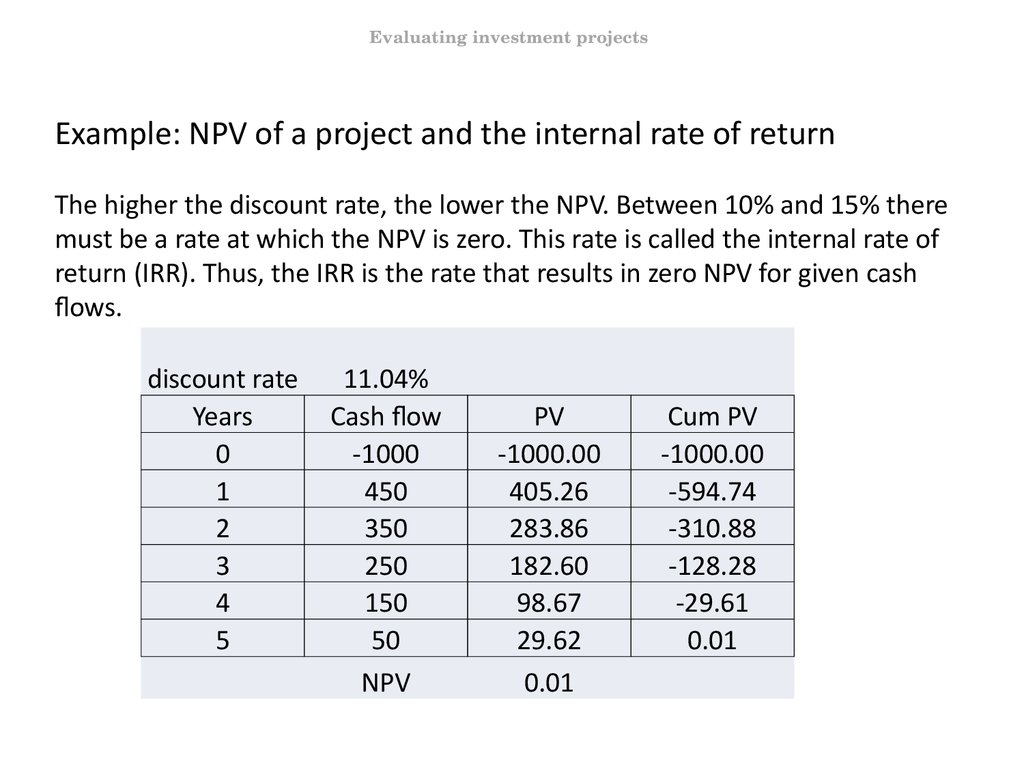

Evaluating investment projectsExample: NPV of a project and the internal rate of return

The higher the discount rate, the lower the NPV. Between 10% and 15% there

must be a rate at which the NPV is zero. This rate is called the internal rate of

return (IRR). Thus, the IRR is the rate that results in zero NPV for given cash

flows.

discount rate

Years

0

1

2

3

4

5

11.04%

Cash flow

-1000

450

350

250

150

50

NPV

PV

-1000.00

405.26

283.86

182.60

98.67

29.62

0.01

Cum PV

-1000.00

-594.74

-310.88

-128.28

-29.61

0.01

98. 98. dia

Evaluating investment projectsNPV and the internal rate of return

From the previous example we can conclude the following:

If the discount rate used to evaluate a project is lower than the IRR, then it has

a positive NPV and should be carried out.

If the discount rate used to evaluate a project is higher than the IRR, then it

has a negative NPV and should not be carried out.

But what is the proper discount rate? You should consider what else you

could do with your money. It is often called the opportunity cost of capital,

because it is the return that is being given up by investing in the project.

Importantly, discount rates also take into account risk. It is still proper to

discount the payoff by the rate of return offered by a comparable investment.

99. 99. dia

Evaluating investment projectsExample (taken from Brealey-Myers):

Obsolete Technologies is considering the purchase of a new computer system

to help handle its warehouse inventories. The system costs $50,000, is

expected to last 4 years, and should reduce the cost of managing inventories

by $22,000 a year. The opportunity cost of capital is 10 percent. Should

Obsolete go ahead?

Note that the computer system does not generate any sales, but if the

expected cost savings are realized, the company’s cash flows will be $22,000 a

year higher as a result of buying the computer. Thus we can say that the

computer increases cash flows by $22,000 a year for each of 4 years.

To calculate present value, we can simply discount each of these cash flows by

10 percent. However, it is smarter to recognize that the cash flows are level

and therefore you can use the annuity formula to calculate the present value:

100. 100. dia

Evaluating investment projectsExample (taken from Brealey-Myers):

1

1

PV (benefits ) cashflow annuityfactor $22000

4

0.1 0.1 1.1

$22000 3.17 $69740

Therefore, the net present value is -$50000+$69740=$19740.

It has a positive NPV, so the firm should purchase the system.

101. 101. dia

Evaluating investment projectsMutually exclusive projects

We speak about mutually exclusive projects if there are two or more projects

that cannot be pursued simultaneously. Examples:

• You could build an apartment block on a vacant site or build an office block.

• You could build a 5-story office block or a 50-story one.

• You could heat it with oil or with natural gas.

• You could build it today, or wait a year to start construction.

When you have to choose between mutually exclusive projects, then calculate

the NPV of each project and choose the one whose NPV is highest.

102. 102. dia

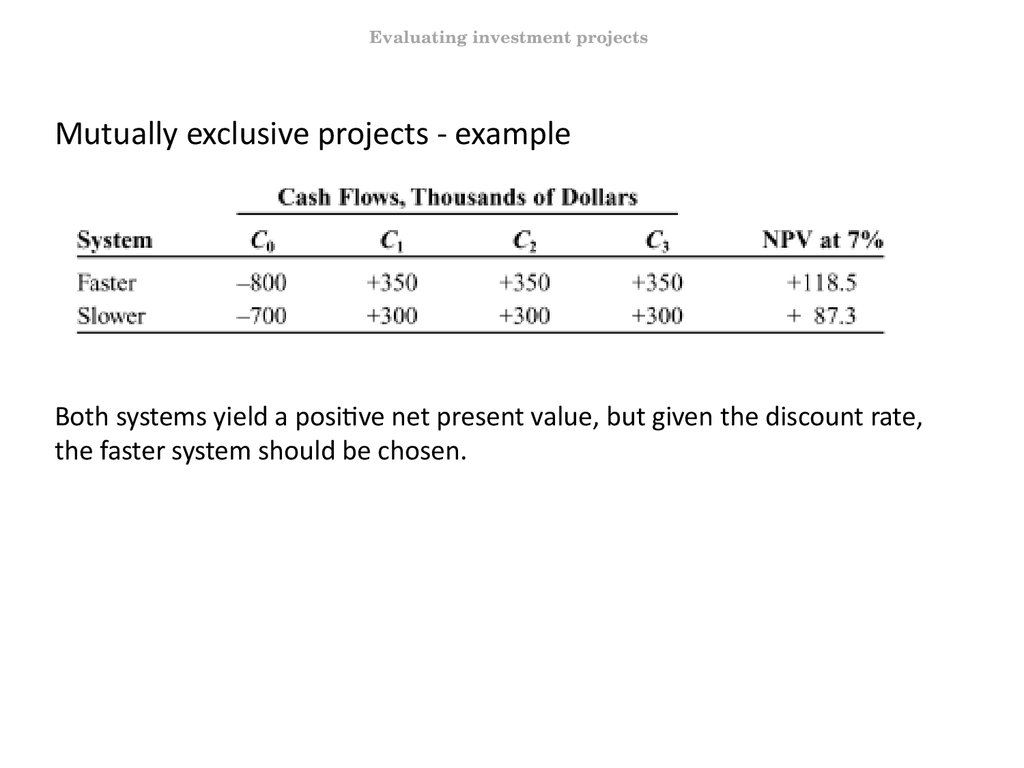

Evaluating investment projectsMutually exclusive projects - example

You are offered two competing softwares to use in your firm to manage

orders. Both have an expected useful life of 3 years, at which point it will be

time for another upgrade. One proposal is for an expensive cutting-edge

system, which will cost $800,000 and increase firm cash flows by $350,000 a

year through increased productivity. The other proposal is for a cheaper,

somewhat slower sy

Финансы

Финансы Английский язык

Английский язык