Похожие презентации:

Materials Science & Engineering A

1.

2.

A. Bhadeligo ct al.Materials Science & Engineering A 918 (2024) 147488

the joint or defect. A joint or defect exceeding 200 pm width is designated as wide gap blazing [15]. In WGB, the braze filler alloy is

composed of a braze alloy with MPD and additional gap filler powder

with a composition similar to that of the base material [14]. The additional alloy powder remains solid during the brazing process and serves

fundamental roles in bridging the large gap between two adjoining

surfaces, acting as a “sink” for boron, and providing capillary pressure to

attract molten braze alloy into the void [14,16]. Furthermore, Yu et al.

[17] reported that the addition of alloy powder into the braze filler alloy

improves the ductility of the wide gap brazed joints compared to joints

brazed solely with the braze alloy. In the diffusion brazing process, the

isothermal solidification occurs by solid-state diffusion of the melting

point depressant (such as boron) into the base material. However, in

case of incomplete isothermal solidification, the brazed joint exhibits the

presence of eutectic-type solidification products [18,19a .

The mechanical properties of brazed joints differ significantly from

those of the individual base materials due to the formation of heterogeneous systems with the substrate material and braze alloy, which results in a complex microstructure [20a . Research has been conducted to

investigate the mechanical properties and fracture behavior of brazed

joints. For example, Henhoeffer et a1. conducted a study on narrow gap

brazed joints of nickel-based alloys X-40 and IN738, analyzing the

high-temperature tensile properties. The as-brazed joint exhibited

higher yield strength but reduced ductility compared to the substrate

material X-40 [3]. Additionally, their investigation on fatigue properties

of narrow and wide gap brazed joints concluded that both NGB and WGB

joints exhibited poor fatigue strength and fatigue lives compared to the

substrate [21]. Similar findings were observed by Shi et a1. [9], indicating a reduction in creep and fatigue lifetime of a brazed joint of

directionally solidified DZ125 superalloy. In addition, the brazing zone

was identified as the weakest point with regard to creep and fatigue

strength at elevated temperatures. Yang et a1. further investigated the

low cycle fatigue (LCF) behavior and its fracture mechanisms of the

DZ125 brazed joint at elevated temperatures. Their findings indicated

that the brazed joint exhibited lower fatigue strength and distinct fracture mechanisms compared to the DZ125 base material [22]. Despite

these efforts, understanding fatigue crack growth (FCG) behavior and

mechanisms in brazed joints remains limited and largely unexplored.

Weiss and Grushko [23] reported the fatigue crack propagation in

brazed joint specimens as uncontrollable. A quantitative characterization of fatigue crack growth behavior in brazed joints remains unaddressed in the existing literature. A more comprehensive understanding

of this behavior is essential for the reliable prediction of the lifetime of

brazed or repaired components and can also provide important inputs to

optimize the brazing process, thereby enhancing the performance of

brazed joints. Additionally, since components made from Alloy 247DS,

such as gas turbine blades, operate in high-temperature environments,

investigating the fatigue crack growth behavior of brazed joints under

such conditions is essential to simulate real-world operating environments and to gain an understanding of how these joints perform under

elevated temperatures.

The present paper aims to address the aforementioned research gaps

and objectives in the following manner: (i) Implement the standard

high-temperature fatigue crack growth experimental technique for

brazed specimens, with required modifications such as stress intensity

factor calculations; (ii) provide a quantitative characterization of fatigue

crack growth in brazed joints of directionally solidified Ni-base alloy; (ii)

explore the influence of grain orientations on fatigue crack growth in

brazed joints at elevated temperatures; and (iv) analyze the microstructure of the brazing seam to elucidate crack growth mechanisms

under cyclic loading.

2. Materials and test methods

2.1. Materials

The base material under investigation was Alloy 247DS, a nickelbased superalloy typically employed in gas turbine blades. Table 1

presents the nominal chemical composition of Alloy 247DS used in this

study. The filler braze alloy used in the brazing process consisted of a

mixture of 75 % Alloy 247 powder and 25 % nickel diffusion braze alloy.

The Amdry BRB (Oerlikon Metco) was chosen as the nickel-based

diffusion braze alloy, and its nominal chemical composition is also

provided in Tulale 4. The Amdry BRB exhibits a solidus temperature of

1055 °C and a liquidus temperature of 1120 °C, respectively. The

blazing temperature of this braze alloy falls within the range of

1177 °C—1232 °C. A recommended diffusion cycle duration is between 2

h and 4 h [24].

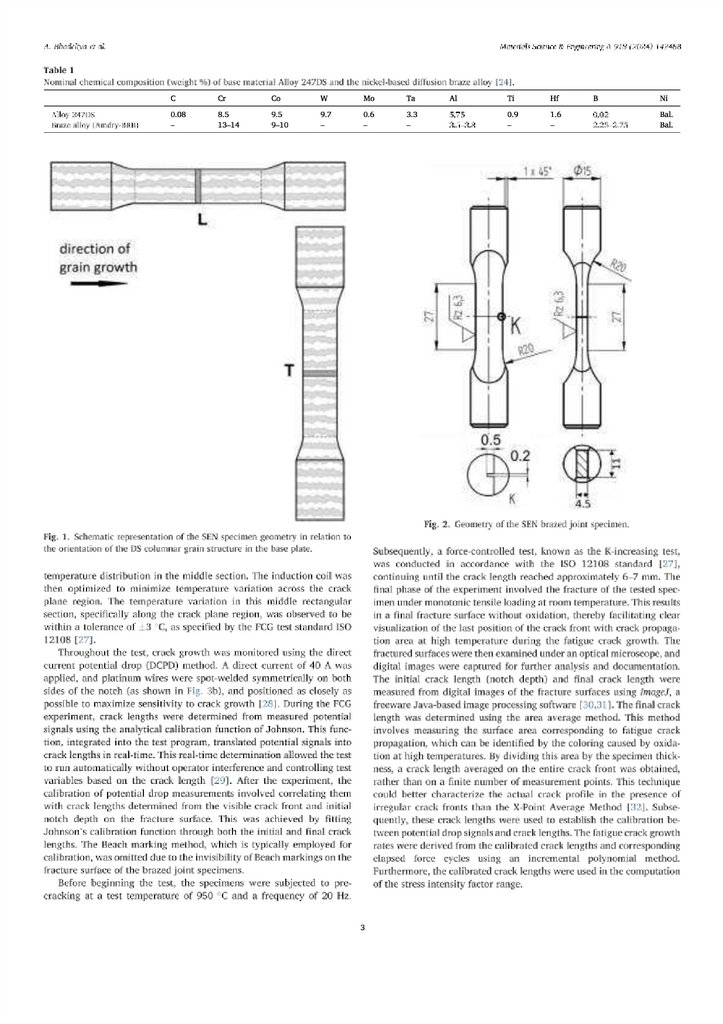

2.2. Test specimen preparation

To produce the brazed joint specimens, two cylindrical base material

parts were initially fabricated from plates of Alloy 247DS of 20 mm

thickness. The base material of Alloy 247DS was solution annealed. This

base material was produced by a directional solidification (DS) casting

process, resulting in a columnar grain orientation. Based on the orientation of these columnar grains in the base material, the brazed joint

specimens were categorized into two groups: specimens with longitudinal grain orientation (L-oriented) and specimens with transverse grain

orientation (T-oriented), as illustrated in Fig. 1. In L-oriented specimens,

the grain orientation aligns parallel to the loading direction; conversely,

for T-oriented brazed specimens, the loading direction is transverse to

the grain orientation. Throughout this article, the test samples are

designated as L-oriented and T-oriented brazed joint specimens.

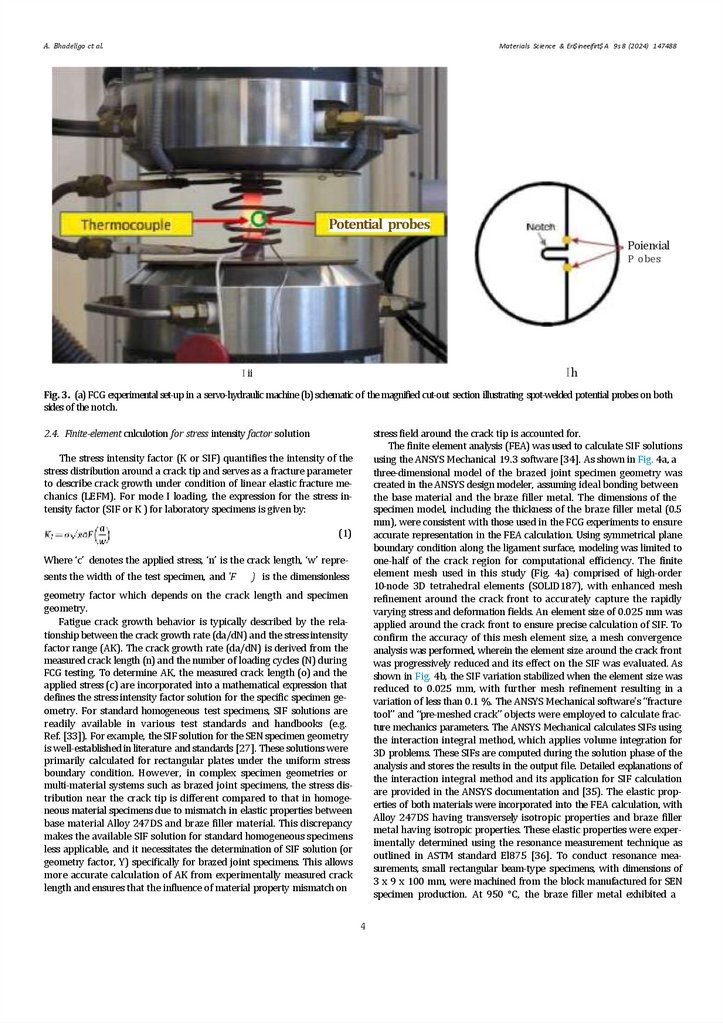

The joining of the two base material parts was accomplished through

a brazing process carried out in a vacuum furnace at a brazing temperature for a duration of 2 h. Subsequently, the brazed parts were

machined into the geometry of the single-edge notch (SEN) specimen. A

schematic illustration of this brazed joint specimen is provided in Fig. 2.

The rectangular gauge section of the SEN specimen was 11 mm x 4.5

mm, with a brazing seam width of 0.5 mm. A through-thickness U-notch

with a depth of 0.5 mm and a root radius of 0.1 mm was introduced via

electric discharge machining (EDM) at the midpoint of the brazing seam.

2.3. Fatigue crack growth tesâng procedure

All fatigue crack growth tests were conducted under load control on

an MTS 370.10 servo-hydraulic testing machine. The machine was

equipped with specimen fixtures aligned (class 2 calibration) according

to ISO 23788 [25] and 100 kN force transducers (class 1 calibration)

calibrated according to ISO 7500-1 [26]. The experimental setup

depicted in Fig. 3a was utilized for the investigation. The test specimens

were subjected to cyclic loading under pure tensile conditions, with

continuous cycling using a triangle waveform at a frequency of 0.5 Hz.

The tests were conducted at an elevated temperature of 950 °C and a

load ratio (R) of 0.1 in a laboratory air environment. Induction heating

was utilized in heating the specimens to the desired test temperature.

The specimen temperature was continuously controlled and measured

using an S-type thermocouple, which was spot-welded at the center of

the gauge length on the side opposite the notch. Before conducting the

FCG tests, the temperature uniformity along the crack plane region of

the specimen was validated. Five thermocouples were attached (three

along the crack plane region and two placed above and below it, each

spaced 3 mm apart) on both the front and back surfaces of a dummy

brazed joint specimen of the same geometry and materials to monitor

2

3.

4.

A. Bhadeligo ct al.Materials Science & Eri$ineeifirt$ A 9s 8 (2024) 147488

Potential probes

Poien‹ial

P obes

Ih

I ii

Fig. 3. (a) FCG experimental set-up in a servo-hydraulic machine (b) schematic of the magnified cut-out section illustrating spot-welded potential probes on both

sides of the notch.

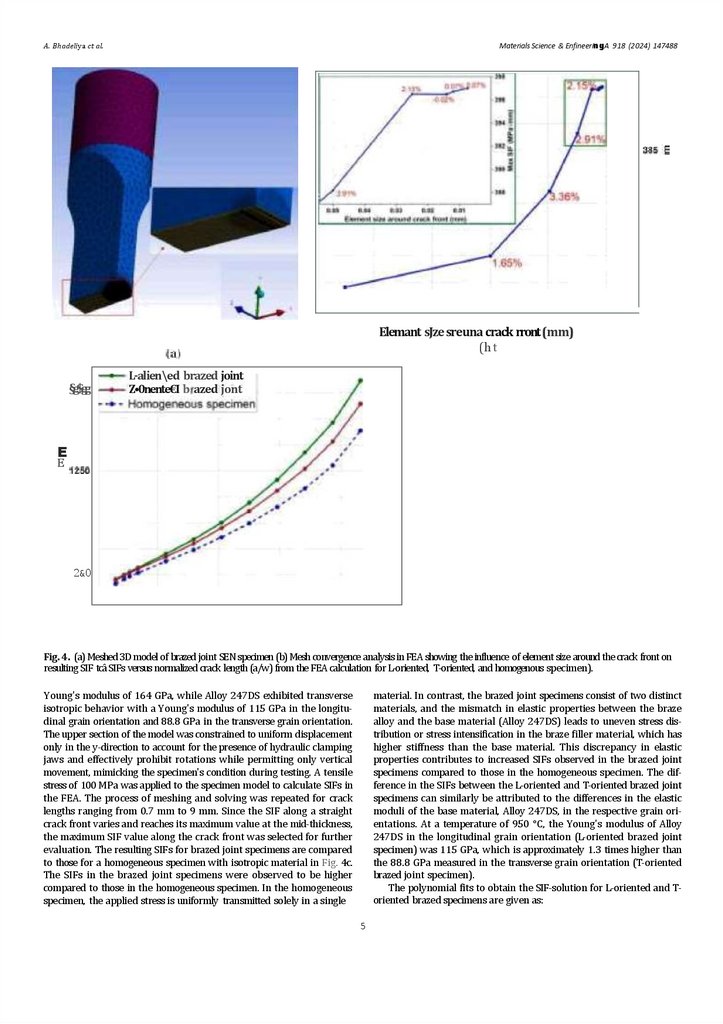

2.4. Finite-element cnlculotion for stress intensity factor solution

stress field around the crack tip is accounted for.

The finite element analysis (FEA) was used to calculate SIF solutions

using the ANSYS Mechanical 19.3 software [34]. As shown in Fig. 4a, a

three-dimensional model of the brazed joint specimen geometry was

created in the ANSYS design modeler, assuming ideal bonding between

the base material and the braze filler metal. The dimensions of the

specimen model, including the thickness of the braze filler metal (0.5

mm), were consistent with those used in the FCG experiments to ensure

accurate representation in the FEA calculation. Using symmetrical plane

boundary condition along the ligament surface, modeling was limited to

one-half of the crack region for computational efficiency. The finite

element mesh used in this study (Fig. 4a) comprised of high-order

10-node 3D tetrahedral elements (SOLID187), with enhanced mesh

refinement around the crack front to accurately capture the rapidly

varying stress and deformation fields. An element size of 0.025 mm was

applied around the crack front to ensure precise calculation of SIF. To

confirm the accuracy of this mesh element size, a mesh convergence

analysis was performed, wherein the element size around the crack front

was progressively reduced and its effect on the SIF was evaluated. As

shown in Fig. 4b, the SIF variation stabilized when the element size was

reduced to 0.025 mm, with further mesh refinement resulting in a

variation of less than 0.1 %. The ANSYS Mechanical software's “fracture

tool” and “pre-meshed crack” objects were employed to calculate fracture mechanics parameters. The ANSYS Mechanical calculates SIFs using

the interaction integral method, which applies volume integration for

3D problems. These SIFs are computed during the solution phase of the

analysis and stores the results in the output file. Detailed explanations of

the interaction integral method and its application for SIF calculation

are provided in the ANSYS documentation and [35). The elastic properties of both materials were incorporated into the FEA calculation, with

Alloy 247DS having transversely isotropic properties and braze filler

metal having isotropic properties. These elastic properties were experimentally determined using the resonance measurement technique as

outlined in ASTM standard El875 [36]. To conduct resonance measurements, small rectangular beam-type specimens, with dimensions of

3 x 9 x 100 mm, were machined from the block manufactured for SEN

specimen production. At 950 °C, the braze filler metal exhibited a

The stress intensity factor (K or SIF) quantifies the intensity of the

stress distribution around a crack tip and serves as a fracture parameter

to describe crack growth under condition of linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM). For mode I loading, the expression for the stress intensity factor (SIF or K ) for laboratory specimens is given by:

(1)

Where ‘c’ denotes the applied stress, ‘n’ is the crack length, ‘w’ represents the width of the test specimen, and 'F

) is the dimensionless

geometry factor which depends on the crack length and specimen

geometry.

Fatigue crack growth behavior is typically described by the relationship between the crack growth rate (da/dN) and the stress intensity

factor range (AK). The crack growth rate (da/dN) is derived from the

measured crack length (n) and the number of loading cycles (N) during

FCG testing. To determine AK, the measured crack length (o) and the

applied stress (c) are incorporated into a mathematical expression that

defines the stress intensity factor solution for the specific specimen geometry. For standard homogeneous test specimens, SIF solutions are

readily available in various test standards and handbooks (e.g.

Ref. [33]). For example, the SIF solution for the SEN specimen geometry

is well-established in literature and standards [27]. These solutions were

primarily calculated for rectangular plates under the uniform stress

boundary condition. However, in complex specimen geometries or

multi-material systems such as brazed joint specimens, the stress distribution near the crack tip is different compared to that in homogeneous material specimens due to mismatch in elastic properties between

base material Alloy 247DS and braze filler material. This discrepancy

makes the available SIF solution for standard homogeneous specimens

less applicable, and it necessitates the determination of SIF solution (or

geometry factor, Y) specifically for brazed joint specimens. This allows

more accurate calculation of AK from experimentally measured crack

length and ensures that the influence of material property mismatch on

4

5.

A. Bhadeliya ct al.Materials Science & EnfineeringA 918 (2024) 147488

Elemant sJzesreuna crack rront (mm)

(h t

§g$gg

L-alien\ed brazed joint

Z•0nente€I b azed jont

E

E

2&0

Fig. 4. (a) Meshed 3D model of brazed joint SEN specimen (b) Mesh convergence analysis in FEA showing the influence of element size around the crack front on

resulting SIF tcâ SIFs versus normalized crack length (a/w) from the FEA calculation for L-oriented, T-oriented, and homogenous specimen).

Young's modulus of 164 GPa, while Alloy 247DS exhibited transverse

isotropic behavior with a Young's modulus of 115 GPa in the longitudinal grain orientation and 88.8 GPa in the transverse grain orientation.

The upper section of the model was constrained to uniform displacement

only in the y-direction to account for the presence of hydraulic clamping

jaws and effectively prohibit rotations while permitting only vertical

movement, mimicking the specimen's condition during testing. A tensile

stress of 100 MPa was applied to the specimen model to calculate SIFs in

the FEA. The process of meshing and solving was repeated for crack

lengths ranging from 0.7 mm to 9 mm. Since the SIF along a straight

crack front varies and reaches its maximum value at the mid-thickness,

the maximum SIF value along the crack front was selected for further

evaluation. The resulting SIFs for brazed joint specimens are compared

to those for a homogeneous specimen with isotropic material in Fig. 4c.

The SIFs in the brazed joint specimens were observed to be higher

compared to those in the homogeneous specimen. In the homogeneous

specimen, the applied stress is uniformly transmitted solely in a single

material. In contrast, the brazed joint specimens consist of two distinct

materials, and the mismatch in elastic properties between the braze

alloy and the base material (Alloy 247DS) leads to uneven stress distribution or stress intensification in the braze filler material, which has

higher stiffness than the base material. This discrepancy in elastic

properties contributes to increased SIFs observed in the brazed joint

specimens compared to those in the homogeneous specimen. The difference in the SIFs between the L-oriented and T-oriented brazed joint

specimens can similarly be attributed to the differences in the elastic

moduli of the base material, Alloy 247DS, in the respective grain orientations. At a temperature of 950 °C, the Young's modulus of Alloy

247DS in the longitudinal grain orientation (L-oriented brazed joint

specimen) was 115 GPa, which is approximately 1.3 times higher than

the 88.8 GPa measured in the transverse grain orientation (T-oriented

brazed joint specimen).

The polynomial fits to obtain the SIF-solution for L-oriented and Toriented brazed specimens are given as:

5

6.

7.

A. Bhadeligo ct al.Materials Science & Eri$ineeifirt$ A 9s 8 (2024) 147488

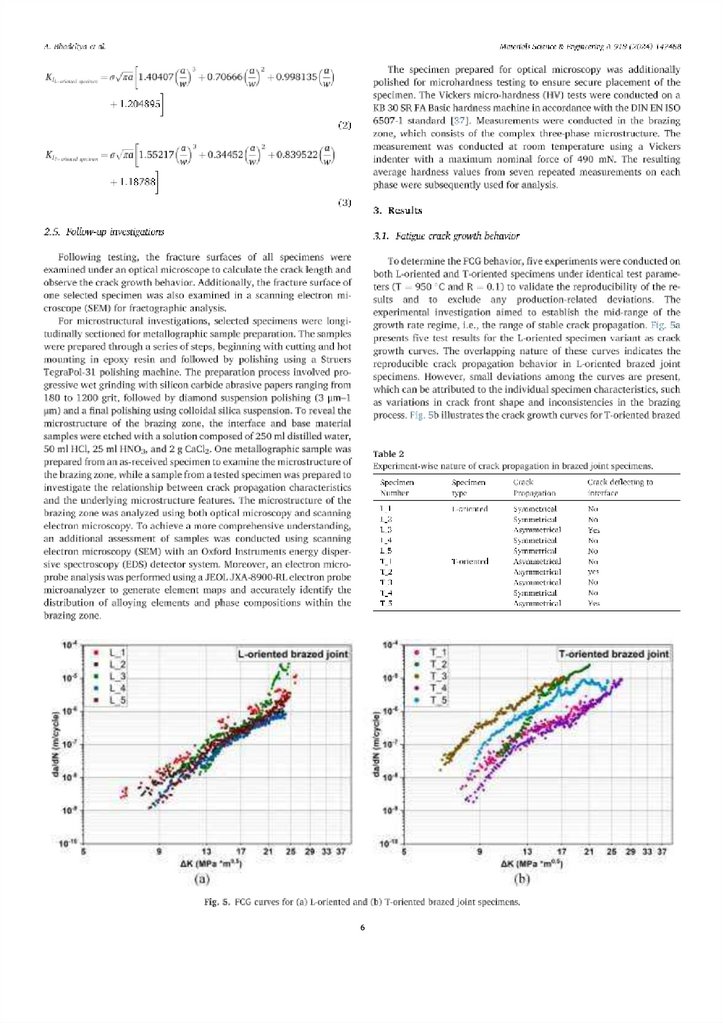

joint specimens. While stable crack propagation is evident, there is

notable scatter among the crack growth curves of different specimens.

These deviations are influenced by distinct crack growth behavior,

which can be understood by examining the respective fracture surfaces

as detailed further in Section 3.2. As presented in Table 2, the facture

surfaces of specimens T_1, T_2, T_3, and T_5 exhibited asymmetrical

crack propagation and/or deflection of the crack to the interface between the braze alloy and base material Alloy 247DS. Consequently, the

fatigue crack growth curve of specimen T_4 is considered more representative and is primarily used for subsequent analysis. The deviation in

these results highlights the complexity of the crack growth behavior in

brazed joints, indicating the contribution of potential microstructural

effects in the observed variability.

Fig. 6 presents the fatigue crack growth curves for L-oriented specimen L_2 and T-oriented specimen T_4. Both specimen types demonstrated stable and symmetrical crack growth behavior within the brazing

zone, without crack deflecting to the interface. The fatigue crack growth

curves of T_4 and L_2 are closely aligned, indicating minimal difference

in crack growth rates between the two orientations. This suggests that

grain orientations in Alloy 247DS within the brazed joint specimens

have no significant influence on the crack growth rate at a temperature

of 950 °C.

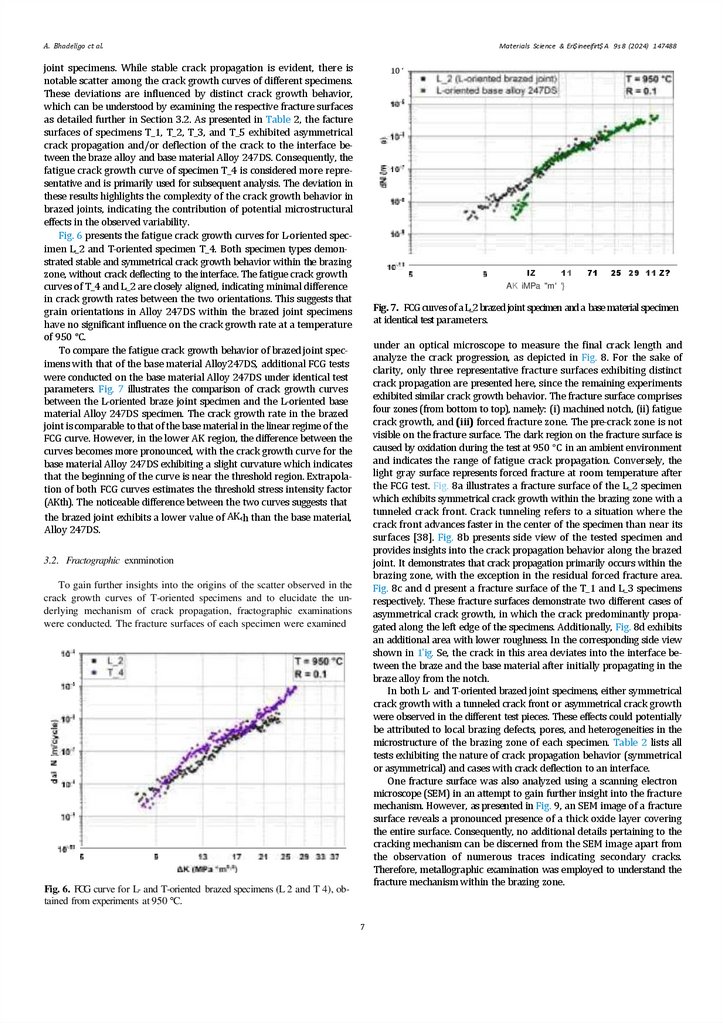

To compare the fatigue crack growth behavior of brazed joint specimens with that of the base material Alloy247DS, additional FCG tests

were conducted on the base material Alloy 247DS under identical test

parameters. Fig. 7 illustrates the comparison of crack growth curves

between the L-oriented braze joint specimen and the L-oriented base

material Alloy 247DS specimen. The crack growth rate in the brazed

joint is comparable to that of the base material in the linear regime of the

FCG curve. However, in the lower AK region, the difference between the

curves becomes more pronounced, with the crack growth curve for the

base material Alloy 247DS exhibiting a slight curvature which indicates

that the beginning of the curve is near the threshold region. Extrapolation of both FCG curves estimates the threshold stress intensity factor

(AKth). The noticeable difference between the two curves suggests that

the brazed joint exhibits a lower value of AK‹h than the base material,

Alloy 247DS.

10 ‘

IZ

11

71

25 29 11 Z?

AK iMPa "m' '}

Fig. 7. FCG curves of a L_2 brazedjoint specimen and a base material specimen

at identical test parameters.

under an optical microscope to measure the final crack length and

analyze the crack progression, as depicted in Fig. 8. For the sake of

clarity, only three representative fracture surfaces exhibiting distinct

crack propagation are presented here, since the remaining experiments

exhibited similar crack growth behavior. The fracture surface comprises

four zones (from bottom to top), namely: (i) machined notch, (ii) fatigue

crack growth, and (iii) forced fracture zone. The pre-crack zone is not

visible on the fracture surface. The dark region on the fracture surface is

caused by oxidation during the test at 950 °C in an ambient environment

and indicates the range of fatigue crack propagation. Conversely, the

light gray surface represents forced fracture at room temperature after

the FCG test. Fig. 8a illustrates a fracture surface of the L_2 specimen

which exhibits symmetrical crack growth within the brazing zone with a

tunneled crack front. Crack tunneling refers to a situation where the

crack front advances faster in the center of the specimen than near its

surfaces [38]. Fig. 8b presents side view of the tested specimen and

provides insights into the crack propagation behavior along the brazed

joint. It demonstrates that crack propagation primarily occurs within the

brazing zone, with the exception in the residual forced fracture area.

Fig. 8c and d present a fracture surface of the T_1 and L_3 specimens

respectively. These fracture surfaces demonstrate two different cases of

asymmetrical crack growth, in which the crack predominantly propagated along the left edge of the specimens. Additionally, Fig. 8d exhibits

an additional area with lower roughness. In the corresponding side view

shown in 1'ig. Se, the crack in this area deviates into the interface between the braze and the base material after initially propagating in the

braze alloy from the notch.

In both L- and T-oriented brazed joint specimens, either symmetrical

crack growth with a tunneled crack front or asymmetrical crack growth

were observed in the different test pieces. These effects could potentially

be attributed to local brazing defects, pores, and heterogeneities in the

microstructure of the brazing zone of each specimen. Table 2 lists all

tests exhibiting the nature of crack propagation behavior (symmetrical

or asymmetrical) and cases with crack deflection to an interface.

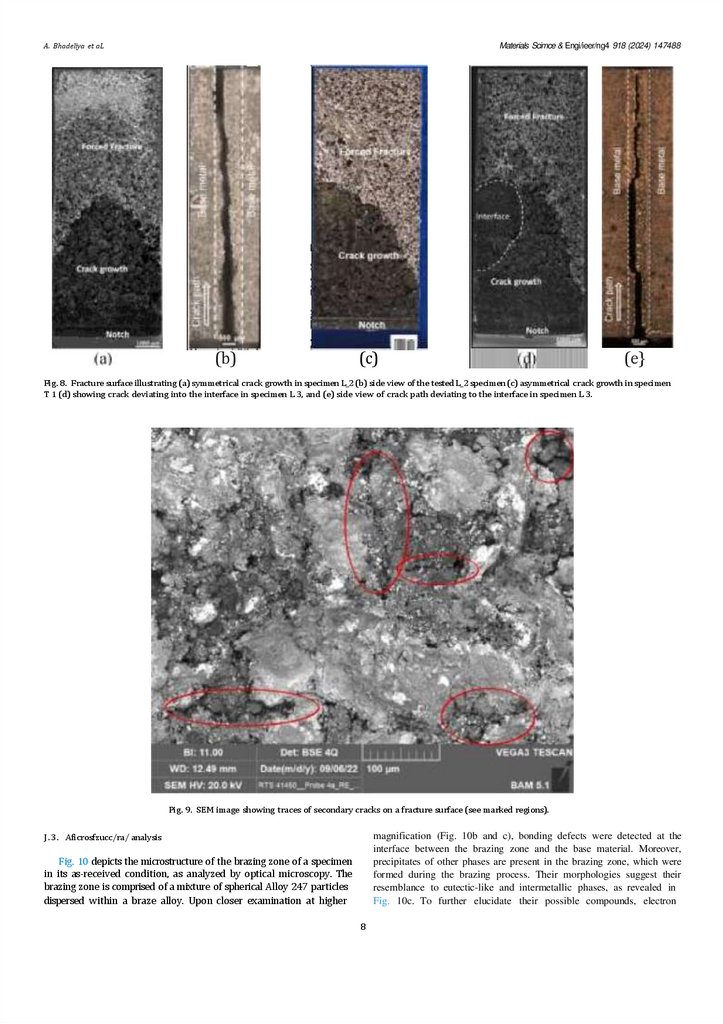

One fracture surface was also analyzed using a scanning electron

microscope (SEM) in an attempt to gain further insight into the fracture

mechanism. However, as presented in Fig. 9, an SEM image of a fracture

surface reveals a pronounced presence of a thick oxide layer covering

the entire surface. Consequently, no additional details pertaining to the

cracking mechanism can be discerned from the SEM image apart from

the observation of numerous traces indicating secondary cracks.

Therefore, metallographic examination was employed to understand the

fracture mechanism within the brazing zone.

3.2. Fractographic exnminotion

To gain further insights into the origins of the scatter observed in the

crack growth curves of T-oriented specimens and to elucidate the underlying mechanism of crack propagation, fractographic examinations

were conducted. The fracture surfaces of each specimen were examined

Fig. 6. FCG curve for L- and T-oriented brazed specimens (L 2 and T 4), obtained from experiments at 950 °C.

7

8.

A. Bhadeliya et aLMaterials Scimce & Engi/ieer/ng4 918 (2024) 147488

(b)

(c)

(e}

Fig. 8. Fracture surface illustrating (a) symmetrical crack growth in specimen L_2 (b) side view of the tested L_2 specimen (c) asymmetrical crack growth in specimen

T 1 (d) showing crack deviating into the interface in specimen L 3, and (e) side view of crack path deviating to the interface in specimen L 3.

Pig. 9. SEM image showing traces of secondary cracks on a fracture surface (see marked regions).

J . 3 . Aficrosfzucc/ra/ analysis

magnification (Fig. 10b and c), bonding defects were detected at the

interface between the brazing zone and the base material. Moreover,

precipitates of other phases are present in the brazing zone, which were

formed during the brazing process. Their morphologies suggest their

resemblance to eutectic-like and intermetallic phases, as revealed in

Fig. 10c. To further elucidate their possible compounds, electron

Fig. 10 depicts the microstructure of the brazing zone of a specimen

in its as-received condition, as analyzed by optical microscopy. The

brazing zone is comprised of a mixture of spherical Alloy 247 particles

dispersed within a braze alloy. Upon closer examination at higher

8

Промышленность

Промышленность